Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities Through Science-based Public Policy

In this section, you will learn:

- Funding for research and programs at NIH, NCI, NIMHD, CDC, and FDA is critical for addressing cancer health disparities.

- Policies that increase access to early detection and promote cancer prevention help reduce cancer health disparities.

- New FDA guidelines bring promise to increasing diversity of clinical trials, but additional enforcement authorities could help implement the voluntary recommendations. Improving insurance coverage and access to high-quality clinical care will help bring new advances to all patients and reduce disparities.

Achieving health equity by eliminating disparities in SDOH and access to care is a bold yet achievable goal and central to the AACR’s mission of preventing and curing all cancers. Creating equitable cancer care will require a multipronged approach to support individuals, communities, health systems, and local, state, and federal governments to eliminate structural racism and systemic barriers to cancer prevention, screening, treatment, and survivorship care. This chapter presents science-based policy solutions to make meaningful progress in addressing cancer health disparities.

Funding for Research and Programs That Address Disparities and Promote Health Equity

Federal investment in NIH, NCI, NIMHD, and CDC is critical for understanding cancer disparities and developing evidence-based strategies to address them. For example, racial and ethnic minorities have been chronically underrepresented in genomic sequencing databases and studies, which harms the ability to leverage precision therapies targeting specific cancer mutations. In an effort to diversify genomic sequencing databases and improve precision medicine, NIH has utilized the All of Us initiative to conduct outreach and gene sequencing for historically underrepresented demographics.

NCI has many initiatives that focus on reducing cancer disparities (see sidebar on NCI Programs that Address Disparities in Cancer Care and Prevention). For example, the NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) engages communities across the United States in clinical research to actively recruit medically underserved patients so clinical trials reflect the patient population intended to be treated. In addition to funding cancer disparities research, the NCI CRCHD helps train a diverse cancer research workforce (see Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities Through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce). NIMHD also supports research on how SDOH influence health risks. Robust, sustained, and predictable, and robust federal funding for these programs at NCI, NIMHD, and other NIH Institutes and Centers is vital to better understand which policy changes help promote health equity; recruit underrepresented patients in cancer research; and support a diverse workforce.

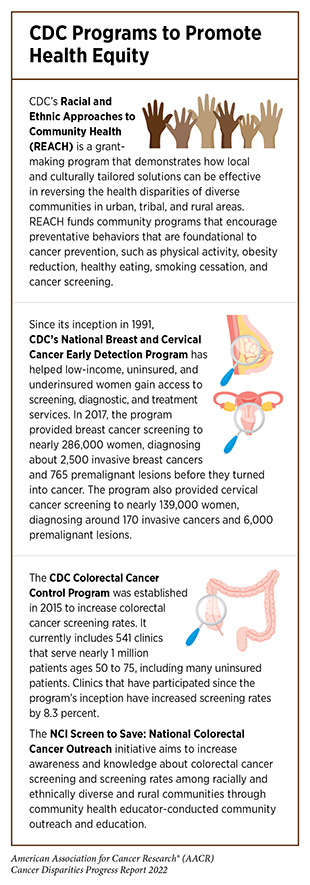

CDC’s many disease prevention programs provide access to cancer care and build health equity, such as the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR), the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH), and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (see sidebar on CDC Programs to Promote Health Equity). Federal investment in these programs enables CDC and local partners to collect data, share public health messages, and provide hundreds of thousands of cancer screenings annually for patients in communities with limited access to screening facilities. AACR advocates for additional investments for CDC to expand the work of the agency in these important areas.

Collaborative Resources to Build Health Equity Partnerships

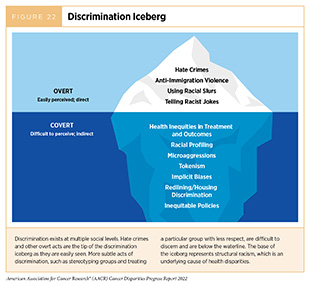

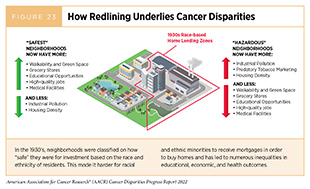

Structural racism is a form of racism that is pervasive throughout systems, laws, practices, and beliefs that reinforce and maintain racial group inequities (861)Paula A. Braveman EA, Dwayne Proctor, Tina Kauh, and Nicole Holm. Systemic and Structural Racism: Definitions, Examples, Health Damages, and Approaches to Dismantling. Health Affairs 2022;41:171-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Structural racism has been described as the hidden base of the “discrimination iceberg” as it supports underlying stereotypical beliefs, overt racism, and discrimination (Figure 22) (862)Wiley. Asian American Communities and Health: Context, Research, Policy, and Action. [updated April 2009, cited 2022 April 22].. For example, redlining is a discriminatory practice in which financial and other services are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as “hazardous” for investment based on race/ethnicity. A growing body of evidence shows that community disinvestment and residing in historically redlined neighborhoods negatively impact physical and mental health (Figure 23) (863)Huang SJ, Sehgal NJ. Association of Historic Redlining and Present-Day Health in Baltimore. PLOS ONE 2022;17:e0261028. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](864)O’Campo P, Xue X, Wang MC, Caughy M. Neighborhood Risk Factors for Low Birthweight in Baltimore: A Multilevel Analysis. American Journal of Public Health 1997;87:1113-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](865)Krieger N, Wye GV, Huynh M, Waterman PD, Maduro G, Li W, et al. Structural Racism, Historical Redlining, and Risk of Preterm Birth in New York City, 2013–2017. American Journal of Public Health 2020;110:1046-53. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](866)Lynch EE, Malcoe LH, Laurent SE, Richardson J, Mitchell BC, Meier HCS. The Legacy of Structural Racism: Associations between Historic Redlining, Current Mortgage Lending, and Health. SSM – Population Health 2021;14:100793. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Alarmingly, residing in historically redlined neighborhoods is also associated with late-stage breast cancer diagnosis and increased rates of mortality in Black women (867)Aghdam N, Carrasquilla M, Wang E, Pepin AN, Danner M, Ayoob M, et al. Ten-Year Single Institutional Analysis of Geographic and Demographic Characteristics of Patients Treated with Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. Front Oncol 2020;10:616286. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](see Social and Built Environments). The complex interplay between social and environmental factors presents several opportunities for government agencies, private funders, and the research community to prioritize cancer equity research.

Cancer health equity would be achieved only when everyone has equal opportunities and capabilities to prevent cancer, detect cancer early, and receive appropriate treatment and survivorship care (868)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Equity in Cancer Prevention and Control. [updated December 16, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Health equity cannot be achieved, however, without considering SDOH, which are conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship and age that affect quality of life outcomes and health risks (87)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social Determinants of Health. [updated August 18, 2020, cited 2022 April 22]. (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities).

As described in Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Health Disparities, biological vulnerabilities at the individual level need to be considered when investigating cancer risks between and across racial and ethnic minorities. Equally important to reaching cancer equity is supporting collaborative efforts among communities, educators, scientists, academic institutions, and federal agencies. Several NIH programs and funding opportunities seek to address disparities and strengthen the cancer workforce pipeline via community engagement.

More than 20 years ago, the NCI CRCHD initiated the Partnerships to Advance Cancer Health Equity (PACHE) program, which provides institutional awards that support partnerships between institutions serving underserved populations and NCI-Designated Cancer Centers (869)National Cancer Institute. Partnerships to Advance Health Equity Pache. [updated February 17, 2015, cited. A promising example of PACHE investment in community-based efforts occurs in Illinois, one of the top states for breast cancer-related deaths among Black and Hispanic women (870)Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative. Background. [updated January 25, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].(871)National Cancer Institute. State Cancer Profiles Illinois. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].(872)Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021;71:7-33. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative (ChicagoCHEC) is a PACHE supported, tri-institutional partnership between Northwestern University, Northeastern Illinois University, and the University of Illinois at Chicago seeking to achieve cancer health equity and support the STEMM workforce (873)Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative. Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. The shared governance model and a community engagement core are bridging the gap between academic institutions, researchers, community residents and leaders, and health care providers to improve cancer health equity (874)Simon MA. Architecture Matters-Moving Beyond “Business as Usual”: The Chicago Cancer Health Equity Collaborative. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2019;13:1-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Similar efforts are underway at Duke Cancer Institute (DCI) in North Carolina, a state with a diverse populace at high risk for cancer and limited access to cancer prevention and treatment resources (875)Barrett NJ, Ingraham KL, Bethea K, Hwa-Lin P, Chirinos M, Fish LJ, et al. Chapter Eight – Project Place: Enhancing Community and Academic Partnerships to Describe and Address Health Disparities. In: Ford ME, Esnaola NF, Salley JD, editors. Advances in Cancer Research: Academic Press; 2020. p 167-88. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Within the DCI patient serving area, the extensive NCI-funded community and academic health assessment, called Project PLACE (Population Level Approaches to Cancer Elimination), was distributed to diverse community partners and collaborators. Respondents included representation from racial and ethnic communities, faith-based organizations, sexual and gender minority community centers, Minority-Serving Institutions, Panhellenic organizations, senior centers, and health clinics. As a result, a five-step blueprint for proactively engaging underserved communities has been designed, with the potential to improve the quality of patient care received at DCI (876)Duke Cancer Institute. Closing the Cancer Disparities Gap in the Age of COVID. [updated March 12, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Federal investments that encourage and strengthen collaboration between NCI, academic institutions, and community-based organizations are imperative to address cancer disparities.

Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Prevention

Regulations to Reduce the Disparate Harms of Tobacco Products

Tobacco use is known to cause 18 different cancers and is the top preventable cause of cancer and cancer-related deaths (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors). Policies such as smoke-free laws, tobacco taxes, advertising restrictions, evidence-based smoking cessation programs, and awareness campaigns have successfully reduced the national cigarette smoking rate from approximately 40 percent to 12.5 percent the past 60 years (213)Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco Product Use among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, predatory marketing practices from the tobacco industry toward racial and ethnic as well as sexual and gender minority individuals have resulted in persistently higher smoking rates compared to NHW individuals, especially among youth (877)Public Health Law Center at Mitchell Hamline School of Law. The Tobacco Industry and the Black Community: The Targeting of African Americans. [updated June 2021, cited 2022 April 22].(878)Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the Prevalence and Correlates of Menthol Cigarette Use in the USA, 2004-2014. Tob Control 2016;25:ii14-ii20. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The tobacco industry has used menthol-flavored cigarettes to aggressively target minority communities (Figure 24). Overall, 38.8 percent of Americans who smoke use menthol cigarettes, and largely due to predatory marketing practices, 85 percent of African Americans who smoke use menthol cigarettes (878)Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Delnevo CD, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Giovino GA. Changes in the Prevalence and Correlates of Menthol Cigarette Use in the USA, 2004-2014. Tob Control 2016;25:ii14-ii20. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Extensive evidence indicates that menthol cigarettes increase smoking initiation, progression to frequent smoking, and exposure to nicotine, and reduce smoking cessation success (230)Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS, Gagosian SY, Abrams DB. Menthol Cigarettes and the Public Health Standard: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2017;17:983. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](879)Ross KC, Dempsey DA, St. Helen G, Delucchi K, Benowitz NL. The Influence of Puff Characteristics, Nicotine Dependence, and Rate of Nicotine Metabolism on Daily Nicotine Exposure in African American Smokers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2016;25:936-43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](880)Okuyemi KS, Faseru B, Sanderson Cox L, Bronars CA, Ahluwalia JS. Relationship between Menthol Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation among African American Light Smokers. Addiction 2007;102:1979-86. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Yet the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (TCA) allowed the tobacco industry to continue marketing menthol cigarettes, while asking FDA to determine if this was “appropriate for the protection of public health.”

In 2013, FDA concluded that “menthol cigarettes pose a public health risk above that seen with nonmenthol cigarettes” (881)Los Angeles Times. FDA Moves toward Restricting Menthol in Cigarettes. [updated July 23, 2013, cited 2022 April 29].. AACR and other public health-focused organizations have consistently urged FDA to prohibit menthol cigarettes, including through a formal Citizen Petition in 2013 (882)Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Citizen Petition to Food & Drug Admin., Prohibiting Mentol as a Characterizing Flavor in Cigarettes. [updated April 12, 2013, cited 2022 April 22].. In April 2022, FDA responded to the Citizen Petition with a draft product standard to prohibit the manufacture, distribution, or sale of menthol cigarettes (883)National Archives and Records Administration. Tobacco Product Standard for Menthol in Cigarettes. [updated April 22, 2022, scited 2022 April 22].. Several studies suggest that between 25 and 64 percent of adults who smoke menthol cigarettes would stop if menthol cigarettes were not available (884)Cadham CJ, Sanchez-Romero LM, Fleischer NL, Mistry R, Hirschtick JL, Meza R, et al. The Actual and Anticipated Effects of a Menthol Cigarette Ban: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1055. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is estimated that a federal menthol ban can save 650,000 lives by 2060, with a large proportion of those lives saved among Black individuals (327)327.Levy DT, Meza R, Yuan Z, Li Y, Cadham C, Sanchez-Romero LM, et al. Public Health Impact of a US Ban on Menthol in Cigarettes and Cigars: A Simulation Study. Tobacco Control 2021:tobaccocontrol-2021-056604. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Concurrent with any ban on menthol, it would be important to increase evidence-based smoking cessation resources and programs to support these new cessation attempts.

In addition to menthol, all flavored tobacco products significantly increase smoking initiation (885)Nyman AL, Sterling KL, Weaver SR, Majeed BA, Eriksen MP. Little Cigars and Cigarillos: Users, Perceptions, and Reasons for Use. Tob Regul Sci 2016;2:239-51. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](886)Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, Conway KP, Borek N, Hyland A, et al. Flavored Tobacco Product Use among US Youth Aged 12-17 Years, 2013-2014. JAMA 2015;314:1871-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](887)Kong G, Bold KW, Simon P, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for Cigarillo Initiation and Cigarillo Manipulation Methods among Adolescents. Tob Regul Sci 2017;3:s48-s58. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While the TCA prohibited flavored cigarettes, it exempted other tobacco products like flavored little cigars and cigarillos. Two thirds of adults who currently use these products have smoked cigars with flavors other than tobacco (885)Nyman AL, Sterling KL, Weaver SR, Majeed BA, Eriksen MP. Little Cigars and Cigarillos: Users, Perceptions, and Reasons for Use. Tob Regul Sci 2016;2:239-51. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, Black and Hispanic adults are more than twice as likely as White adults to smoke little cigars or cigarillos. In April 2022, FDA proposed a draft product standard banning the manufacture, distribution, or sale of flavored cigars (888)National Archives and Records Administration. Tobacco Product Standard for Characterizing Flavors in Cigars. [updated April 3, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. This policy is estimated to prevent 112,000 youth and young adults from initiating cigar smoking every year, and therefore decrease premature deaths from cigar smoking by 21 percent (889)L. Rostron B, G. Corey C, Holder-Hayes E, K. Ambrose B. Estimating the Potential Public Health Impact of Prohibiting Characterizing Flavors in Cigars Throughout the US. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019;16:3234. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

AI/AN adults are nearly 40 percent more likely to smoke cigarettes compared to any other population groups in the United States (890)Odani S, Armour BS, Graffunder CM, Garrett BE, Agaku IT. Prevalence and Disparities in Tobacco Product Use among American Indians/Alaska Natives – United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1374-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], partly due to predatory marketing practices from the tobacco industry (891)Lempert LK, Glantz SA. Tobacco Industry Promotional Strategies Targeting American Indians/Alaska Natives and Exploiting Tribal Sovereignty. Nicotine & Tobacco Research : Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 2019;21:940-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In 2022, the Navajo Nation took bold action to reduce tobacco-related health disparities among Navajo communities by implementing a comprehensive ban on commercial tobacco products on tribal lands, except for private use in the home or traditional tobacco for ceremonial purposes (892)National Cancer Institute. Air Is Life: The Navajo Nation’s Historic Commercial Tobacco Ban. [updated February 7, 2022, cited 2022 April 22]..

Lack of health insurance and inconsistent coverage of evidence-based smoking cessation therapies also contribute to smoking-related health disparities. Among U.S. adults who attempted to stop smoking in 2015, 34.3 percent of NHW adults used evidence-based medication or counseling (893)Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting Smoking among Adults – United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;65:1457-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In comparison, 28.9 percent of Black adults, 20.5 percent of Asian adults, and 19.2 percent of Hispanic adults used evidence-based cessation methods. A key reason for these disparities was the lack of health insurance; only 21.4 percent of adults without health insurance used evidence-based methods. Expanding Medicaid, improving cessation benefits within Medicaid and Medicare, and eliminating other barriers could greatly improve the use of evidence-based cessation methods that reduce overall health care costs (894)Richard P, West K, Ku L. The Return on Investment of a Medicaid Tobacco Cessation Program in Massachusetts. PLOS ONE 2012;7:e29665. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](895)Ramsey AT, Prentice D, Ballard E, Chen L-S, Bierut LJ. Leverage Points to Improve Smoking Cessation Treatment in a Large Tertiary Care Hospital: A Systems-Based Mixed Methods Study. BMJ open 2019;9:e030066. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, increased funding for federal awareness campaigns and cessation support services, such as SmokeFree.gov and CDC’s “Tips from Former Smokers,” with focused initiatives for racial and ethnic and/or SGM populations could help address tobacco-related disparities (896)Smokefree.gov. Tools & Tips. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].(897)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips from Former Smokers. [updated April 25, 2022, cited 2022 April 29]..

Eliminating Cervical Cancer and Reducing the Burden of Other HPV-Driven Cancers

HPV is known to cause six different types of cancer among men and women, including nearly all cases of cervical cancer (see Infectious Agents). Fortunately, HPV vaccines significantly reduce the risk of developing an HPV infection and related cancers when administered before the age of 17 years (884)Cadham CJ, Sanchez-Romero LM, Fleischer NL, Mistry R, Hirschtick JL, Meza R, et al. The Actual and Anticipated Effects of a Menthol Cigarette Ban: A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1055. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](898)Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, Moreira ED, Penny ME, Aranda C, et al. Efficacy of Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine against HPV Infection and Disease in Males. New England Journal of Medicine 2011;364:401-11. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](899)Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, Moreira ED, Aranda C, Jessen H, et al. HPV Vaccine against Anal HPV Infection and Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia. New England Journal of Medicine 2011;365:1576-85. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, only 58.6 percent of Americans ages 13 to 17 years were fully vaccinated against HPV in 2020 (365)Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage among Adolescents Aged 13-17 Years – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1183-90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and NHW adolescents, particularly those living in rural areas, persistently experience the lowest vaccination rates (900)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Supplementary Tables for Estimated Vaccination Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Doses among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years and Total Survey Error—National Immunization Survey–Teen, United States, 2020. [updated.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires health insurance plans, including Medicaid expansion plans, to cover all vaccines recommended by the CDC Advisory Council on Immunization Practices without a copayment (901)Department of Health Policy School of Public Health and Health Services The George Washington University Medical Center. The Affordable Care Act: U.S. Vaccine Policy and Practice. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. State-level vaccination requirements to attend public schools for other deadly diseases, like measles and polio, have been effective strategies to nearly eradicate those viruses (902)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization. [updated August 3, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. However, only Hawaii, Rhode Island, Virginia, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia have such requirements for HPV vaccination (903)National Conference of State Legislatures. HPV Vaccine: State Legislation and Regulation. [updated May 26, 2020, cited 2022 April 22].. Also, tailored and culturally sensitive communication is critical to improving vaccination rates.

In addition to HPV vaccines, cervical cancer can be effectively prevented with routine cancer screenings and minor surgical removal of precancerous or early-stage cancerous lesions. By utilizing vaccines, early detection, and follow-up care, the World Health Organization has called on public health authorities around the world to eliminate cervical cancer globally by 2030 (904)World Health Organization. Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. [updated June 22, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. More than 80 U.S.-based public health organizations, including AACR, have signed on to related recommendations to eliminate cervical cancer within the United States (905)American Association for Cancer Research. Health Organizations, Patient Advocates to Congress: We Can and Must Eliminate HPV-Related Cancer. [updated June 27, 2019, cited 2022 April 22].. As described earlier, low access to screening and especially follow-up treatment services for racial and ethnic minority women, and uninsured women, drives disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the United States (see Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection). Increased funding for CDC’s NBCCEDP, as well as mobile screening units organized by cancer centers, is critical for improving access to cervical cancer screening in medically underserved communities (see sidebar on Guidelines for and Disparities in Screening for Five Cancer Types). Legislation such as the PREVENT HPV Cancers Act (H.R. 1550) would enhance awareness efforts by authorizing $25 million to support national awareness campaigns about HPV vaccinations and early detection, with a focus on rural areas and communities with lower rates of vaccination or screening.

Addressing Obesity, Malnutrition, and Physical Inactivity

When the interconnected impacts of obesity, malnutrition, and physical inactivity on cancer risk are combined, these factors are associated with increased risk of 15 types of cancer and cause nearly as many cases of cancer as smoking tobacco (906)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and Cancer. [updated February 18, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Obesity promotes cancer by elevating growth signals and increasing the availability of nutrients that collectively enable cancer cells to grow more rapidly. Obesity also poses unique challenges for patients with cancer undergoing active treatment, such as surgical complications and restrictions on chemotherapy options (907)Slawinski CGV, Barriuso J, Guo H, Renehan AG. Obesity and Cancer Treatment Outcomes: Interpreting the Complex Evidence. Clinical Oncology 2020;32:591-608. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are many social, cultural, and economic factors that contribute to disparities in obesity rates, including: economic and educational discrimination that results in lower incomes; lack of green spaces to safely exercise outdoors; absence of grocery stores in a community (areas that are considered “food deserts”); overabundance of fast foods in a community (areas that are considered “food swamps”); lack of education on healthy nutrition; inability to walk or bike around a neighborhood; discrimination in housing through practices such as redlining; ongoing and historic injustices against racial and ethnic minorities; and many others. Since factors driving obesity are multifaceted and often driven by structural racism and wide-ranging policies, reducing obesity and eliminating disparities will require broad policy changes at all levels of government, private industry, and health systems (see Body Weight, Diet, and Physical Activity).

With devastating job losses during the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affecting racial and ethnic minorities (908)U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity, 2020. [updated November 2021, cited 2022 April 22]., there was a concern that the ability to afford healthy food could decrease and thus worsen disparities. In response, Congress increased nutritional and unemployment benefits in several COVID-19 relief bills in 2020 and 2021 (909)Kiaser Family Foundation. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Summary of Key Provisions. [updated March 23, 2020, cited 2022 April 22].(910)Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. States Are Using Much-Needed Temporary Flexibility in Snap to Respond to COVID-19 Challenges. [updated October 4, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Additionally, USDA revised the federal “Thrifty Food Plan” benchmark for nutrition programs to reflect the growing cost of healthy foods in August 2021 (911)U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA Modernizes the Thrifty Food Plan, Updates Snap Benefits. [updated August 16, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. This action increased Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits by $36.24 per month per beneficiary, the largest increase in the program’s history. This increase particularly benefited children, who comprised 43 percent of SNAP beneficiaries in 2019, as well as African American and Hispanic residents who comprised 30.8 percent and 19.1 percent of beneficiaries, respectively (912)U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support. Characteristics of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Households: Fiscal Year 2019. [updated March 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, CDC programs, such as REACH, supported community partners to promote physical activity and access to fresh fruit and vegetables in underserved communities (913)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reach Program Impact | Dnpao. [updated March 10, 2020, cited 2022 April 22]..

To comprehensively address the obesity epidemic, policies to address SDOH, like housing affordability, availability of healthy food, walkable neighborhoods, educational opportunities, and green spaces for physical activity, must be considered (914)Trust for America’s Health. The State of Obesity 2021: Better Policies for a Healthier America. [updated September 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. These efforts will require collaboration with a wide variety of stakeholders outside the health sector.

Policies to Promote Environmental Justice

As detailed earlier in the report (see Exposure to Environmental Carcinogens), exposure to environmental carcinogens disproportionately impacts racial and ethnic minorities (391)Lane HM, Morello-Frosch R, Marshall JD, Apte JS. Historical Redlining Is Associated with Present-Day Air Pollution Disparities in U.S. Cities. Environmental Science & Technology Letters 2022;9(4):345-350. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For example, radon exposure was estimated to cause approximately 10 percent of all lung cancers in the United States during the 1990s (915)Gaskin J, Coyle D, Whyte J, Krewksi D. Global Estimate of Lung Cancer Mortality Attributable to Residential Radon. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126:057009. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Families with lower incomes and/or those who rent their homes are less likely to have their properties tested for radon or have mitigating technology installed if high radon levels are found (916)Minnesota Department of Health. Radon Mitigation Rates in Metro Area Reflect Disparities in Income, Housing, Home Values. [updated January 7, 2020, cited 2022 April 22].(917)Stanifer SR, Rayens MK, Wiggins A, Hahn EJ. Social Determinants of Health, Environmental Exposures and Home Radon Testing. West J Nurs Res. 2022;44:636-642. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In 2015, EPA launched a public private partnership with nonprofit and industry organizations to create the National Radon Action Plan (NRAP), which has saved an estimated 2,000 lives per year (196)NIIH’s All of Us Research Program Releases First Genomic Dataset of Nearly 100,000 Whole Genome Sequences. [updated cited(918)U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The National Radon Action Plan – a Strategy for Saving Lives. [updated January 28, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].(919)U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Epa and Partners Make Progress on the National Radon Action Plan, Saving Nearly 2,000 Lives Yearly from Radon-Induced Lung Cancer. [updated May 20, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. NRAP has improved building codes to become more radon-resistant; increased testing requirements in the mortgage process; created and shared technical standards; and raised awareness. In partnership with EPA, Kansas State University operates the National Radon Program Services, which provides low-cost radon test kits(920)Kansas State University National Radon Program. Radon Test Kits Available for Purchase. [updated October 23, 2020, cited 2022 April 22]., and many states have programs to provide free or low-cost radon testing and mitigation services. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development announced a new $4 million pilot grant program in January 2022 to provide radon testing and mitigation for low-income families (921)U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Hud Announces $4 Million Radon Testing Notice of Funding Opportunity. [updated January 26, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. These programs have greatly helped mitigate radon exposures, and necessitate new research to update estimates for the impact of radon on lung cancer rates.

Since 1990, EPA has regulated 188 hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act to protect public health (922)U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Initial List of Hazardous Air Pollutants with Modifications. [updated January 5, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. Unfortunately, elevated rates of cancer incidence as well as severe respiratory and neurological health complaints in heavily polluted communities have persisted over the past three decades (923)ProPublica. Poison in the Air. [updated November 2, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].(924)Reuters. Formosa Plastics to Pay Nearly $3 Mln to Settle Air Pollution Charges. [updated September 13, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].(925)NOLA.com. Firestone Polymers of Sulphur to Pay More Than $3.35m to Settle Air Pollution Complaints. [updated February 23, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].(926)Tampa Bay Times. Poisoned. [updated March 24, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Partly due to housing discrimination and low incomes preventing residents from leaving, many of the areas most impacted by heavy industrial pollution are predominantly racial and ethnic minority communities. In early 2022, EPA announced the Environmental Justice initiative (927)U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Journey to Justice. [updated February 10, 2022, cited 2022 April 22]., which included some of the strongest actions ever taken to reduce industrial air pollution, primarily in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. These are as follows:

- Create a new Pollution Accountability Team to increase unannounced inspections.

- Utilize $20 million of grants from the 2021 American Rescue Plan to increase air pollution monitoring capabilities in historically polluted communities.

- Require some heavily polluting sites to install new monitoring systems or pollution reduction devices.

- Reduce allowable emissions of the carcinogen, ethylene oxide, by 2,000-fold.

- Appoint a Senior Advisor for Environmental Justice.

- Reinstate regulations for power plant emissions of hazardous air pollutants from 2016.

In October 2021, EPA also announced the first-ever agency-wide strategic plan to address pollution from poly- or perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) (928)U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. PFAS Strategic Roadmap: EPA’s Commitments to Action 2021-2024. [updated January 27, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. PFAS are carcinogens known for their long-lasting stability in nature and human bodies. Emerging evidence suggests racial and ethnic minorities are disproportionately impacted by PFAS pollution from industrial, military, and food packaging sources (929)Park SK, Peng Q, Ding N, Mukherjee B, Harlow SD. Determinants of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Midlife Women: Evidence of Racial/Ethnic and Geographic Differences in Pfas Exposure. Environ Res 2019;175:186-99. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](930)Union of Concerned Scientists. PFAS Contamination Is an Equity Issue, and President Trump’s EPA Is Failing to Fix It. [updated October 30, 2019, cited 2022 April 22].. Rural areas in Michigan that use PFAS-contaminated biosolid waste from water treatment plants as agricultural fertilizer have dangerously high levels of PFAS in the soil, water, and livestock (931)Michigan Live. Advisory Warns of Pfas in Beef from Michigan Cattle Farm. [updated January 28, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. A key provision of EPA’s new plan is to create an enforceable safe drinking water standard that will require routine testing for the two most common PFAS chemicals in tap water systems. Other plans include new regulations to limit discharge of PFAS into waterways; requiring polluters to pay for decontaminating PFAS within the Superfund program; leveraging $10 billion from the bipartisan infrastructure law to clean up PFAS in drinking water; and researching additional types of PFAS and emissions sources to inform future actions. In addition to these bold new actions, the House-passed PFAS Action Act will provide greater regulatory authority to EPA over PFAS pollution if it becomes law.

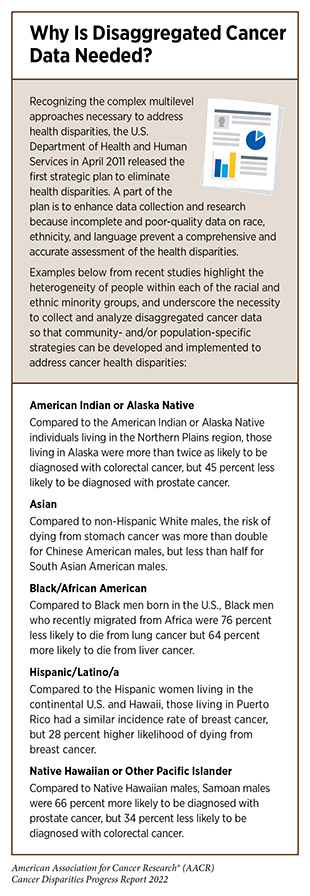

Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Screening and Follow Up

As described in Collaborative Resources to Build Health Equity Partnerships, structural racism is an underlying driver for cancer health disparities (see also Figure 5; and Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities). Routine cancer screenings are necessary to detect precancerous lesions as early as possible in cancer development; however, variability along the cancer screening continuum presents challenges to improving equity (see Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection). For example, cancer screenings for cervical (932)Lee D-C, Liang H, Chen N, Shi L, Liu Y. Cancer Screening among Racial/Ethnic Groups in Health Centers. International Journal for Equity in Health 2020;19:43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], breast (933)Susan G. Komen. How Do Breast Cancer Screening Rates Compare among Different Groups in the U.S. [updated March 3, 2022, cited 2022 April 22]., colorectal (932)Lee D-C, Liang H, Chen N, Shi L, Liu Y. Cancer Screening among Racial/Ethnic Groups in Health Centers. International Journal for Equity in Health 2020;19:43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and lung (934)Lozier JW, Fedewa SA, Smith RA, Silvestri GA. Lung Cancer Screening Eligibility and Screening Patterns among Black and White Adults in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2130350. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] cancer are equally or more likely to occur in minority communities at health centers when compared to NHW populations. Follow-up care, however, is less likely to occur in minority populations for several reasons including being uninsured or underinsured, decreased access to care, healthcare system bias, and miscommunication with health care providers (4)Kaiser Family Foundation. Racial Disparities in Cancer Outcomes, Screening, and Treatment. [updated February 3, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. For sexual and gender minorities, cancer screening data are limited because national cancer screening programs do not collect sexual orientation or gender identification data (935)Haviland KS, Swette S, Kelechi T, Mueller M. Barriers and Facilitators to Cancer Screening among LGBTQ Individuals with Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2020;47:44-55. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (see Cancer Health Disparities Among Other Medically Underserved Populations). Self-reported concerns regarding discrimination are an additional barriers to cancer screenings for sexual and gender minorities (935)Haviland KS, Swette S, Kelechi T, Mueller M. Barriers and Facilitators to Cancer Screening among LGBTQ Individuals with Cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2020;47:44-55. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These knowledge gaps, screening eligibility criteria, concerns about discrimination, and variable screening data among racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minorities present opportunities for policies that increase insurance coverage for low-income individuals. Collecting disaggregated cancer data (see sidebar on Why Is Disaggregated Cancer Data Needed?), providing opportunities to report sexual orientation, and improving cultural competency across the health care system are viable approaches to improving equity.

Inadequate health insurance coverage is more prevalent among racial and ethnic minorities and is associated with not completing recommended care (936)Fiscella K, Humiston S, Hendren S, Winters P, Jean-Pierre P, Idris A, et al. Eliminating Disparities in Cancer Screening and Followup of Abnormal Results: What Will It Take? J Health Care Poor Underserved 2011;22:83-100. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Addressing cancer screening needs of the underinsured and those that are low income is a priority of the CDC’s NBCCEDP and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP). However, funding challenges prevent servicing all program-eligible individuals (937)Tangka F, Kenny K, Miller J, Howard DH. The Eligibility and Reach of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program after Implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Cancer Causes & Control. 2020;31:473-89. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Increased federal investment is needed to achieve equity in cancer screening and follow-up. There is growing evidence that expanding Medicaid is associated with detecting breast cancer at an earlier stage (938)Le Blanc JM, Heller DR, Friedrich A, Lannin DR, Park TS. Association of Medicaid Expansion under the Affordable Care Act with Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis. JAMA Surgery 2020;155:752-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], demonstrating that expanding Medicaid coverage to historically underserved populations is another substantive approach to achieving health equity.

Community health centers are patient-directed organizations that deliver comprehensive, culturally and linguistically competent, and high-quality care and that accept patients without insurance (939)Health Resources and Services Administration. What Is a Health Center? [updated August 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Community health centers receive Health Center Program federal grant funding to improve the health of underserved populations, but cancer prevention services vary due to underfunding, high staff turnover, and differences in the meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) (940)Huguet N, Hodes T, Holderness H, Bailey SR, DeVoe JE, Marino M. Community Health Centers, Performance in Cancer Screening and Prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2022;62:e97-e106. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A March 2022 workshop held by the National Cancer Policy Forum and the Computer Science and Telecommunications Board discussed opportunities to redevelop the use of EHRs in oncology care, research, and surveillance as the first generation EHRs were intended for medical billing and not health care research (941)National Academies. Innovation in Electronic Health Records for Oncology Care Research and Surveillance a Workshop. [updated February 21, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. Transforming EHRs has the potential to standardize cancer management pathways, collect data for evidence-based care, and minimize provider burden. This will require coordinated efforts between the federal government, state, tribal, local, and territorial health professionals, and EHR vendors.

Policies to Address Disparities in Clinical Research and Care

Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers in Trial Design

Participating in clinical trials often improves outcomes for patients with cancer (942)Han JJ, Kim JW, Suh KJ, Kim J-W, Kim SH, Kim YJ, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Enrolled in Clinical Trials Compared with Those of Patients Outside Clinical Trials in Advanced Gastric Cancer. Asia-Pacific J Clin Oncol 2019;15:158-65. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](943)Koo KC, Lee JS, Kim JW, Han KS, Lee KS, Kim DK, et al. Impact of Clinical Trial Participation on Survival in Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Multi-Center Analysis. BMC Cancer 2018;18:468. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](944)Narui K, Ohno S, Mukai H, Hozumi Y, Miyoshi Y, Yoshino H, et al. Overall Survival of Participants Compared to Non-Participants in a Randomized-Controlled Trial (Select Bc): A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2527. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] and drives improvements in overall survival rates (945). Historically, racial and ethnic minority populations have been underrepresented in clinical trials, resulting in FDA-approved medical products that have not been adequately tested in a diverse sampling of patients that reflects how the products will be used in clinical practice (see Disparities in Clinical Research and Cancer Treatment). Unfortunately, more than 75 percent of patients with cancer are ineligible to participate in clinical trials because either a trial is unavailable for their disease or strict eligibility criteria exclude them from studies (534).

In November 2020, FDA issued voluntary guidance to encourage trial sponsors to increase representation of historically underserved minorities in clinical trials (527). Some key provisions are:

- Expand eligibility criteria for large clinical trials when safety data for the new therapies should be well established;

- Propose strategies to ensure the intended patient population is adequately represented in clinical trials;

- Recommend studies to include sufficient numbers of participants from key demographics, when possible, to conclusively identify differences in safety and efficacy;

- Decentralize clinical trials by collaborating with local health facilities; and

- Leverage real-world evidence to fill in knowledge gaps when randomized clinical trials may not be possible.

Guidance from federal agencies represent important first steps in loosening eligibility criteria and improving clinical trial design. However, enforcement mechanisms could greatly accelerate change. It is critical to engage stakeholders in the policy-making process to help identify solutions to change traditional patterns and increase access to clinical trials for all patients. As stated in the AACR Call to Action, Congress should pass the Diverse and Equitable Participation in Clinical Trials (DEPICT, H.R. 6584) Act to provide FDA with the authority to require diverse representation in clinical trials (946).

Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers for Patients

When offered, 58.4 percent of Black patients with cancer and 55.1 percent of White patients with cancer choose to join a clinical trial (150). However, many patients are never asked by their health care providers. Additional barriers such as the absence of clinical trial sites in the community, financial costs associated with trial participation, dependent care responsibilities, lack of paid leave from work, and many other factors reduce clinical trial participation (150,534,947,948).

Financial barriers to clinical trial participation include medical costs, transportation costs, lodging costs, and loss of wages. The ACA required Medicare and private insurance plans to cover routine medical costs related to clinical trial participation, but deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs can still pose significant challenges. Following passage of the CLINICAL TREATMENT Act in December 2020, all Medicaid programs are also required to cover medical costs of clinical trial participation. As included in FDA’s 2020 guidance, further decentralization of clinical trials and use of telemedicine could be powerful tools to reduce the time and financial burdens of participating in trials (see Achieving Equity in Clinical Cancer Research) (527,949). The Diversifying Investigations Via Equitable Research Studies for Everyone (DIVERSE) Trials Act (H.R. 5030/S. 2706) would further support decentralization of trials through telemedicine and remote data collection, as well as allow trial sponsors to help offset the costs of transportation and other expenses related to participation (950).

Engaging community partners to raise awareness about clinical trials is a powerful tool to increase diversity. For example, in April 2019, FDA Oncology Center of Excellence created Project Community to promote the benefits of clinical trials participation in historically underserved areas (951). Furthermore, research networks like NCORP conduct clinical trials at sites outside of large research centers—the traditional sites for clinical trials— and have developed strong partnerships with the communities served. Numerous studies have shown that trusted patient navigators, community health workers, and patient advocates can effectively support enrollment and retention of racial and ethnic minority patients in clinical trials, as well as educating patients about their disease and the trial process. However, funding streams for these crucial workers are often temporary and unsustainable. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and/or Congress should support routine reimbursement for these essential members of the health care workforce.

Improving Access to High-Quality Clinical Care

Insurance coverage is well-demonstrated to increase patient access to health care services, including for treatment and management of cancer. Following passage of the ACA, roughly 20 million people who lacked insurance gained coverage through ACA marketplaces or Medicaid expansion (931). In 2020, an estimated 70 percent (232 million) of Americans were covered by private or public health plans included in the ACA provision that requires coverage of preventive services, such as most cancer screening recommended by the USPSTF, without any out-of-pocket expenses (952). The largest gain in access to cancer treatment was found in states that chose to expand Medicaid under the ACA; in expansion states the percentage of low-income patients with cancer who lacked health insurance decreased from 9.6 percent to 3.6 percent between 2011 and 2013, compared to a decrease from 14.7 percent to 13.3 percent in states that did not expand Medicaid (953). The ACA and Medicaid expansion were also correlated with increased detection of early-stage colorectal, lung, breast, melanoma, and pancreatic cancers and increased access to cancer surgeries (954). Other studies found that Medicaid expansion increased access to cancer survivorship care (955), and nearly eliminated racial disparities related to timely cancer treatment (955).

The ACA and Medicaid expansion have also decreased the rates of patients with cancer who delayed care or were unable to afford prescriptions or services, especially women and NHB patients (956-959). However, patients with high-deductible plans or limited provider networks, known as undersinsured, may still face financial challenges with health care (960-962). Therefore, underinsurance can continue to exacerbate health disparities by incentivizing patients to wait to seek medical care until they can no longer tolerate their symptoms. This leads to more advanced cancers being diagnosed that entail more expensive procedures and medications. It is important to address gaps in access to care that ultimately drive up overall health care costs and premiums. Additionally, states that have not yet expanded Medicaid could significantly decrease cancer disparities and improve access to care by choosing to expand.

Furthermore, IHS provides comprehensive health care services for 2.6 million AI/AN (963). Unfortunately, chronic underfunding of IHS has contributed to severe health disparities and dangerously outdated health care facilities that have an average age of 40 years, compared to the national average of 10.6 years (964,965). Additionally, IHS spends less than $4,000 per year per beneficiary on health care, compared to more than $13,000 per Medicare beneficiary (3.5-fold greater) or $9,500 for veterans (2.5-fold greater) in the Veterans Affairs health system. IHS is in desperate need of additional investment from Congress to adequately serve the health needs of AI/AN, especially those living in remote rural areas without other options for health care services.

Special categories of hospitals, such as Safety Net Hospitals, Critical Access Hospitals, and Sole Community Hospitals, are essential for providing access to health care for their respective patient populations and addressing cancer disparities (966,967). These types of hospitals provide the majority of uncompensated care to uninsured and underinsured patients, as well as disproportionately care for patients who live in rural and underserved urban areas (967a). It is estimated that nearly thirty million adults in the United States were uninsured in 2019 (967b). Since poverty, unemployment, and uninsured rates are disproportionately high among racial and ethnic minority populations, the safety net system provides care to a disproportionately high volume of these patients (967c). Safety net institutions by definition have fewer per capita dollars available for health care, and are therefore less likely to have the financial resources available to support clinical trials infrastructure or remain operational during times of crisis and financial strain. As a consequence, inadequate funding of public hospitals contributes to the underrepresentation of minorities in cancer clinical research.

The costs of caring for patients with COVID-19 devastated Safety Net Hospitals, because of the pandemic severity and resulting economic losses among racial and ethnic minority groups. As the safety net institutions resumed routine health maintenance practices following the pandemic shutdown, they were faced with the burden of catching up with cancer screening and treatment for an even larger population of uninsured and underinsured patients, but with even more constrained budgets (967d). Partnering with cancer centers is one effective strategy to increase capacity to care for patients with cancer and conduct cancer screenings (967e).

Additionally, the ACA authorized Medicare and Medicaid to provide reimbursement adjustment bonuses to help subsidize uncompensated care at safety net hospitals (968). The federal 340B Drug Pricing Program also allows eligible facilities to buy prescription drugs at a discount from pharmaceutical companies and then be reimbursed at the full cost through private and public insurance plans (969). Despite these subsidies, more than 100 rural hospitals closed between 2013 and February 2020 (970), and several dozen more closed or declared bankruptcy during the pandemic (971). Increased investment in these critical medical facilities is vital to ensure underserved communities continue to have local access to health care.

Sustainably Supporting Patient Navigators and Community Health Workers

As described throughout this report, patient navigators and community health workers can greatly assist health prevention initiatives and help connect patients to health systems, clinical trials, and community resources (859). Furthermore, patient navigators and community health workers are instrumental in addressing health disparities by connecting patients with health care and community resources (638,856,858). However, funding for these vital health care workers is often short-term and unsustainable. A crucial step to increase the sustainability of patient navigation is the recognition of the profession by creation of a Payroll-Based Journal job title code by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which would enable reimbursement. Currently, 15 states reimburse community health workers through Medicaid programs, and another 10 hire community health workers through Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (972). Expanding sustainable reimbursement models within Medicare and private insurance plans for community health workers and patient navigators could greatly improve the health status of historically medically underserved communities while reducing costs.

Enhancing Coverage of Lymphedema Maintenance Treatments

As described earlier (see Disparities in Cancer Survivorship), disparities in lymphedema contribute to worse outcomes in quality of life for cancer survivors who are racial and ethnic minorities and patients without private health insurance. The standard to treat lymphedema is “comprehensive decongestive therapy,” delivered in two phases (973-975): 1) acute therapy with trained providers performing manual lymph drainage, assisting with exercises, and applying compression bandages; 2) maintenance therapy at home with manual lymph drainage, exercises, and compression garments. While Medicare covers acute therapy (976), it is not allowed by law to cover compression bandages because they fall into a grey zone of nondurable medical equipment (977). The Lymphedema Treatment Act was originally introduced to Congress in 2010 with the goal of requiring Medicare coverage of compression garments; the current version of the bill has bipartisan cosponsors representing strong majorities of both the Senate and the House (978,979), but has not yet been enacted. Addressing this gap in coverage would greatly improve the affordability and access to lymphedema-related garments to reduce disparities in cancer survivorship.

Advocacy for Universal Access to High-Speed Broadband Internet

The COVID-19 pandemic and widespread adoption of telehealth have highlighted the importance of reliably fast Internet speeds in the modern era. However, an estimated 42 million Americans do not have access to broadband Internet with download speeds of at least 25 Mbps needed to stream video (980). Rural communities and historically marginalized urban communities are disproportionately impacted by limited Internet access. Lack of high-speed Internet harms many aspects of the communities affected, including the ability to receive telehealth, attend school remotely and do homework, start businesses, and work from home (981,982).

Through the Telecommunications Act of 1996, Congress and the Federal Communications Commission created a nonprofit organization, Universal Service Administrative Co. (USAC), to oversee federal programs to expand high-speed Internet access to underserved areas. USAC now leverages more than $8 billion per year in federal funds to support Internet infrastructure and telehealth (983). Additionally, the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure law provided $65 billion to further support broadband access and lower costs for low-income families (984). Several local governments, mainly in rural areas, have also created their own broadband and fiber Internet networks that effectively and affordably connect their communities with some of the highest Internet speeds in the country (985). Unfortunately, 18 states restrict or prohibit municipal Internet projects (986). Federal and local support for Internet access will be vital for bridging the digital divide and creating equity in health care and in educational and economic opportunities.

Coordination of Health Disparities Research and Programs Within the Federal Government

As described throughout this chapter, the negative impact of structural racism is pervasive throughout the cancer care continuum. There are several initiatives across all branches of the U.S. federal government aimed at addressing the impact of structural racism on perpetuating cancer disparities. CRCHD manages and coordinates several disparities-related research and training programs; NCORP engages communities across the United States in clinical research to actively recruit minority and underserved patients to clinical trials; and NIMHD supports research on the influence of SDOH on disease risks.

Within the judicial and legislative branches, there are also increased efforts to reduce the impact of structural racism on health outcomes. As of October 2021, the Department of Justice announced the launch of the “Combating Redlining Initiative,” its most powerful initiative to address lending discrimination in the past 50 years (987). Concurrently, there are hundreds of introduced bills in Congress that have the potential to promote health equity. In addition to increasing coordination between these programs across all branches of government, it is necessary to recognize the importance of disaggregating racial and ethnic demographics data. Underrepresented minorities and historically undeserved groups are not monolithic. It will take concerted efforts to understand the diversity that lies within each group to address and remedy cancer disparities. To intentionally address the health care needs of historically underserved groups and improve cancer outcomes, continued, meaningful collaboration across all branches of government and sustained, robust, and predictable funding for CDC and NIH, specifically NCI, are needed.