Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors

In this section, you will learn:

- In the United States, four out of 10 cancer cases are associated with modifiable risk factors.

- Decades of systemic inequities and social injustices have led to adverse differences in drivers of health causing a disproportionately higher burden of cancer risk factors among US racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations.

- Vaccinating against human papillomavirus and hepatitis B and not using tobacco are some of the most effective ways a person can prevent cancer from developing.

- Nearly 20 percent of US cancer diagnoses are estimated to be related to excess body weight, alcohol intake, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity.

- Certain segments of the US population have higher than average exposure to occupational and environmental carcinogens, increasing their risk of cancer.

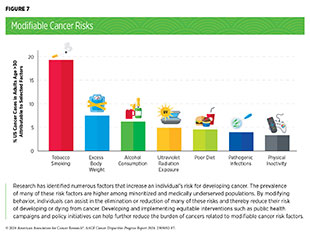

Research in basic, translational, and population sciences has broadened our understanding of the factors that increase an individual’s risk of developing cancer. Modifiable risk factors, including tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, ultraviolet (UV) light exposure, alcohol consumption, pathogenic infections, and obesity, contribute to the development of 40 percent of all cancers. Given that several of these risks can be avoided, such as eliminating tobacco use or receiving vaccinations against pathogenic infections, many cases of cancer could potentially be prevented (see Figure 7). It is recognized, however, that some of these risk factors are less avoidable in some communities because of many structural barriers they face. Environmental risk factors, such as air pollution, water contamination, and naturally occurring radon gas, increase a person’s risk for certain types of cancer, including common cancers like lung cancer. Furthermore, occupations such as firefighting and those involving night-shift work can expose individuals to factors that increase their risk of developing cancer.

Emerging data indicate that certain cancer risk factors are also associated with worse outcomes after a cancer diagnosis, including development of secondary cancers. In addition, cancer risk factors contribute to other chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and diabetes. Strategies that mitigate exposure to the wide range of avoidable cancer risk factors have the potential to reduce the burden of cancer and other debilitating conditions.

Systemic Inequities and Social Injustices

Long-standing inequities in numerous social drivers of health (SDOH) (see Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities) contribute to significant disparities in the burden of preventable cancer risk factors among socially, economically, and geographically disadvantaged populations. These disparities stem from decades of structural, social, and institutional injustices, placing disadvantaged populations in unfavorable living environments and contributing to behaviors that increase cancer risk.

Public education and policies aimed at reducing the burden of cancer risk factors, such as tobacco cessation or physical activity–promoting interventions, are useful. For example, adherence to nutrition and physical activity guidelines led to a 28 percent to 42 percent reduction in the risk of obesity-related cancers in both Black and Latina women, respectively (290)Pichardo MS, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128: 3630. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, it is important to note that individual behaviors are strongly influenced by the surrounding environment. Unfortunately, neighborhoods where socioeconomically disadvantaged populations reside are often characterized by low walkability, reduced availability of healthy food options including fresh fruits and vegetables, and limited outdoor space for recreation and exercise (291)Shams-White MM, et al. (2021) Prev Med Rep, 22: 101358. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](292)Heredia NI, et al. (2020) J Immigr Minor Health, 22: 555. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These areas, often with historic redlining, have reduced tree canopy cover, which increases average temperatures (293)American Forests. Tree Equity Score National Explorer. Accessed: March 26, 2024. .

Socioeconomically vulnerable populations are also more likely to reside in less favorable locations such as near highways, busy roads, or industries, which increases their exposure to air pollution increasing cancer risk (97)Lane HM, et al. (2022) Environ Sci Technol Lett, 9: 345. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](294)Hajat A, et al. (2015) Curr Environ Health Rep, 2: 440. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](295)Boing AF, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2213540. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Occupations that increase exposure to cancer risk factors are also more likely to be staffed by minoritized and underserved populations (296)Juon HS, et al. (2021) Prev Med, 143: 106355. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For instance, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) and Hispanic/Latino individuals are more likely to have permanent night-shift work, which has been shown to increase the likelihood of certain types of cancers (297)Ferguson JM, et al. (2023) Chronobiol Int, 40: 310. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Cancer risk factors can intersect with other population characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and disability status, among others, to drive cancer disparities. As one example, individuals with disabilities, who may have fewer occupational opportunities and lower income, also have higher prevalence of smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity. It is imperative that public health experts prioritize cancer prevention efforts that account for the complex and interrelated factors across institutional, social, and individual levels that influence personal risk exposure and disparate health outcomes. There is an urgent need for all members of the medical research community to come together and develop strategies that enhance the dissemination of our current knowledge of cancer risk reduction and implement evidence-based interventions for reducing the burden of cancer for everyone.

Tobacco Use

The use of tobacco products is the leading preventable cause of cancer and is associated with the development of 17 different types of cancer in addition to lung cancer. Nearly 20 percent of all cancer cases and 30 percent of all cancer-related deaths are caused by tobacco products (131)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2023-2024. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . In the United States, between 80 percent and 90 percent of lung cancer deaths are attributable to smoking (298)Warren GW, et al. (2013) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013:359 [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. On average, people who smoke die 10 years younger than those who have never smoked (299)Jha P, et al. (2013) N Engl J Med, 368: 341. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Research over the past 50 years has consistently demonstrated that byproducts released from smoking tobacco products, such as cigarettes, cause permanent cellular and molecular alterations, which lead to cancer (300)Alexandrov LB, et al. (2016) Science, 354: 618. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](301)Pezzuto A, et al. (2019) Future Sci OA, 5: FSO394. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](302)Yang Y, et al. (2023) J Hazard Mater, 455: 131556. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, smoking causes many other chronic conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and many types of cardiovascular diseases.

Thanks to nationwide tobacco control initiatives, cigarette smoking among US adults has been declining. In fact, cigarette smoking rates among US adults have decreased from 42.4 percent in 1965 to 11.5 percent in 2021 (303)Cornelius ME, et al. (2023) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 72: 475. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, even in 2021, the most recent year for which such data are available, an estimated 46 million US adults reported using any tobacco product (e.g., cigarettes, cigars, pipes) (303)Cornelius ME, et al. (2023) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 72: 475. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In the most recent decade between 2011 and 2020, there have been decreases in smoking among non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black, and Hispanic adults. However, during the same time period, there was an increase of 29,700 American Indian or Alask Native (AI/AN) individuals who smoked, even though rates of smoking among NH AI/AN adults remained the same (304)Arrazola RA, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E45. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are striking sociodemographic disparities in the use of tobacco products as well as in exposure to secondhand smoke. Overall tobacco use is higher among US residents who live in rural areas and in the Midwest, those with lower levels of household income and educational attainment, those who are uninsured or insured by Medicaid, and those experiencing psychological distress or have a disability (303)Cornelius ME, et al. (2023) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 72: 475. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](305)Loretan CG, et al. (2022) Prev Chronic Dis, 19: E87. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, US adults who identify as belonging to the SGM populations have higher rates of using tobacco products.

Exposure to secondhand smoke, which occurs when people inhale smoke exhaled by people who smoke or from burning tobacco products, has declined from 27.7 percent between 2009 and 2010 to 20.7 percent between 2017 and 2018 (306)Brody D, et al. (2021) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 70: 224. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], the most recent time for which such data were available. Despite this decline, secondhand smoke is estimated to cause 41,000 deaths each year among adults in the United States, with 7,300 deaths attributed to lung cancer, the primary cancer associated with secondhand smoking (307)US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Unfortunately, Black adults who do not smoke are consistently exposed to nearly twice as much secondhand smoke as Hispanic, NH White, and Asian adults (306)Brody D, et al. (2021) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 70: 224. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Black individuals are 16 percent less likely to survive 5 years after diagnosis with lung cancer compared to NH White individuals (308)American Lung Association. State of Lung Cancer 2023. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Although the exact mechanisms are not known, increased exposure to secondhand smoke, comorbidities, and higher use of mentholated cigarettes among Black adults could contribute to this disparity. (306)Brody D, et al. (2021) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 70: 224. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]

Because lung cancer is often associated with smoking, patients with lung cancer without a history of smoking or very brief history of smoking, such as Daniel West, may experience societal stigma (309)Williamson TJ, et al. (2020) Ann Behav Med, 54: 535. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](310)Diaz D, et al. (2022) Tob Induc Dis, 20: 38. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](311)Carter-Harris L (2015) J Am Assoc Nurse Pract, 27: 240. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](312)Cataldo JK, et al. (2012) Eur J Oncol Nurs, 16: 264. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It should be noted that about 12 percent of newly diagnosed lung cancer cases occur in individuals who have never smoked (313)Siegel DA, et al. (2021) JAMA Oncol, 7: 302. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is an urgent need for more research to identify lung cancer risk factors among these individuals and to determine whether the incidence rate of lung cancer among those without a history of smoking is increasing.

There is strong evidence that smoking cessation has both immediate and long-term health benefits, especially when stopping at a younger age. Evidence from a large cohort study demonstrated that among individuals who stopped smoking before age 45, all-cause mortality was similar to that of a person who never smoked (314)Thomson B, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2231480. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Those who stop smoking reduce their risk of developing cancers of the larynx, oral cavity, and pharynx by half after 10 years of cessation (315)Ahmed AA, et al. (2015) Circ Heart Fail, 8: 694. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](316)Duncan MS, et al. (2019) JAMA, 322: 642. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. After 20 years, the risk of developing these cancers is lowered to the same level as someone who never smoked (315)Ahmed AA, et al. (2015) Circ Heart Fail, 8: 694. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](316)Duncan MS, et al. (2019) JAMA, 322: 642. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

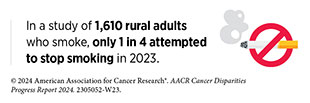

People who smoke often have difficulty stopping and, while more than half attempt smoking cessation every year, only 7.3 percent of smokers manage to successfully stop smoking (317)Watkins SL, et al. (2020) Nicotine Tob Res, 22: 1560. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), it was found that 63.4 percent of Black, 69.4 percent of Asian, and 69 percent of NHOPI people who smoke attempted to quit smoking within the previous year, compared to only 53.3 percent of NH White people (318)Babb S, et al. (2017) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65: 1457. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Evidence-based interventions at local, state, and federal levels, including tobacco price increases, public health campaigns, marketing restrictions, cessation counseling, FDA-approved medications, and smoke-free laws, must be utilized to continue the downward trend of tobacco use. Unfortunately, while certain groups, including Black individuals, are more likely to report their willingness to stop smoking (28)Giaquinto AN, et al. (2022) CA Cancer J Clin, 72: 202. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], there are disparities in access to tobacco cessation interventions. A large analysis of Medicaid beneficiaries across all 50 US states from 2009 to 2014 found that Black, Latino, Asian, and AI/AN individuals had lower rates of access to smoking cessation medication and counseling compared to White beneficiaries (319)Flores MW, et al. (2024) J Racial Ethn Health Disp, 11: 755. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Over 70 percent of NH Black adults who smoke report that they want to stop; however, this population does not receive information to the same degree as NH White people (318)Babb S, et al. (2017) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65: 1457. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Only 56 percent of NH Black adults report receiving advice from their doctors about ways to quit smoking, and NH Black adults are 65 percent less likely to receive this advice compared to White people who smoke (318)Babb S, et al. (2017) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65: 1457. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](321)Zhang L, et al. (2019) Am J Prev Med, 57: 478. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The use of culturally tailored smoking cessation programs that incorporate individual-level counseling can significantly improve engagement and increase abstinence and rates of attempted cessation across many groups (322)Wen KY, et al. (2023) J Racial Ethn Health Disp, DOI: 10.1007/ s40615-023-01760-w. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](323)Presant CA, et al. (2023) J Clin Med, 12: 1275. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](324)Casas L, et al. (2023) Addict Behav Rep, 17: 100478. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](325)Tan ASL, et al. (2023) Am J Prev Med: 66: 840. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Flavored tobacco products, such as menthol cigarettes, pose a significant health risk because they lead to increased nicotine dependence and reduced smoking cessation compared to nonmentholated cigarettes (326)Villanti AC, et al. (2021) Nicotine Tob Res, 23: 1318. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](327)Watkins SL, et al. (2022) J Adolesc Health, 71: 226. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Overall, 38.8 percent of Americans who smoke use menthol cigarettes (328)Villanti AC, et al. (2016) Tob Control, 25: ii14. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Use of menthol cigarettes is higher among certain racial and ethnic minority populations, particularly NH Black people, with 85 percent of Black individuals who smoke using menthol cigarettes (328)Villanti AC, et al. (2016) Tob Control, 25: ii14. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The disparity in menthol cigarette use can be attributed to tobacco industries aggressively marketing to these populations through advertisements, giveaways, price reductions, lifestyle branding, and event sponsorships. It has been estimated that between 1980 and 2018, 1.5 million NH Black individuals began smoking menthol cigarettes and 157,000 NH Black individuals died prematurely because of menthol cigarette smoking (329)Mendez D, et al. (2022) Nicotine Tob Control, 31: 569. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Evidence shows that young adults are more likely to try menthol cigarettes and those who do are more likely to continue smoking into adulthood (326)Villanti AC, et al. (2021) Nicotine Tob Res, 23: 1318. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition, 40.4 percent of middle and high school students who smoke report using menthol cigarettes (305)Loretan CG, et al. (2022) Prev Chronic Dis, 19: E87. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This is greater than the percentage of adults who smoke menthol cigarettes. Use of menthol cigarettes is 20 percent higher in NH Black and 18 percent higher in Hispanic youth compared to NH White youth who smoke (330)Sawdey MD, et al. (2020) Nicotine Tob Res, 22: 1726. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The use of other combustible tobacco products (e.g., cigars), smokeless tobacco products (e.g., chewing tobacco and snuff), and waterpipes (e.g., hookahs) is also associated with adverse health outcomes including cancer.

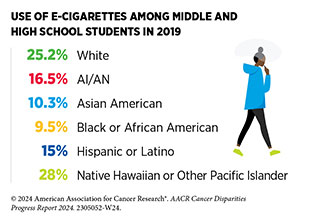

E-cigarettes, first introduced in 2006 in the United States, have gained popularity among those who have never smoked, with the long-term health consequences of these products still unknown. Therefore, it is concerning that in 2023, 10 percent of middle and high school students used e-cigarettes, with 25 percent of those using e-cigarettes daily (331)Birdsey J, et al. (2023) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 72: 1173. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Of middle and high school students who used e-cigarettes daily, nearly nine out of 10 reported using flavored e-cigarette products (331)Birdsey J, et al. (2023) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 72: 1173. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Fortunately, the use of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products among middle and high school students are declining, with a 10 percent reduction in the use of these products between 2022 and 2023 (331, 332). Despite the downward trends, these numbers are still of concern, as research shows that nine out of 10 adults who smoke cigarettes daily first try smoking by age 18 (333)Hu T, et al. (2020) J Am Heart Assoc, 9: e014381. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The landscape of e-cigarette devices has evolved over the years to include different types of products, such as prefilled pods (e.g., JUUL) or cartridge-based and disposable devices (e.g., Puff Bar), among others. E-cigarettes can deliver nicotine, a highly addictive substance that is harmful to the developing brain, at levels similar to those of traditional cigarettes (334)Prochaska JJ, et al. (2022) Tob Control, 31: e88. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unlike combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes come in flavors, such as cotton candy and bubblegum, that appeal to youth and are key drivers of e-cigarette use among youth and young adults (335)National Academy of Sciences. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Accessed: July 6, 2023. .

Recent estimates show that e-cigarette usage was highest among individuals ages 18 to 24 years, with 18.6 percent reporting current use (337)Erhabor J, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2340859. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. E-cigarette use is higher among bisexual individuals compared to heterosexual individuals, as well as among transgender individuals compared to cisgender individuals (337)Erhabor J, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2340859. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

While e-cigarettes emit fewer carcinogens than combustible tobacco, they still expose individuals to many toxic chemicals, including metals that can damage DNA and trigger inflammation (338)Goniewicz ML, et al. (2018) JAMA Netw Open, 1: e185937. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](339)Herbst RS, et al. (2022) Clin Cancer Res, 28: 4861. . Furthermore, people who use e-cigarettes (among other electronic nicotine delivery systems) are between 2.9 and 4 times more likely to ever smoke a combustible cigarette than people who have never used e-cigarettes (339)Herbst RS, et al. (2022) Clin Cancer Res, 28: 4861. . Further research is warranted on e-cigarettes and their long-term effects, especially in teens and young adults so that appropriate preventive interventions could be implemented.

Another area where more research is needed is the health consequences of smoking marijuana; for example, there is concern among public health experts that it could cause cancer because it involves the burning of an organic material, much like smoking tobacco (340)Ghasemiesfe M, et al. (2019) JAMA Netw Open, 2: e1916318. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The need for this research is driven by the growing number of states that have legalized marijuana use for medical and/or recreational purposes. Currently in the United States, 74 percent of Americans live in a state where marijuana is legal for either recreational or medical use (341)Pew Research Center. Most Americans now live in a legal marijuana state – and most have at least one dispensary in their county. Accessed: March 26, 2024. .

Body Weight, Diet, and Physical Activity

Nearly 20 percent of new cancer cases and 16 percent of cancer deaths in US adults are attributable to a combination of excess body weight, poor diet, physical inactivity, and alcohol consumption (342)Islami F, et al. (2018) CA Cancer J Clin, 68: 31. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](343)Islami F, et al. (2019) JAMA Oncol, 5: 384. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Following a healthier lifestyle may reduce the risk of developing certain cancers as well as other adverse health outcomes. In the United States, decades of systemic and structural racism have contributed to adverse differences in SDOH in racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations (see Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities). Racial inequality in income, employment, and homeownership, stemming from structural racism, has led to built environments that limit opportunities to maintain a healthy weight, such as participating in physical activities and recreation, and eating a healthy diet.

Obesity

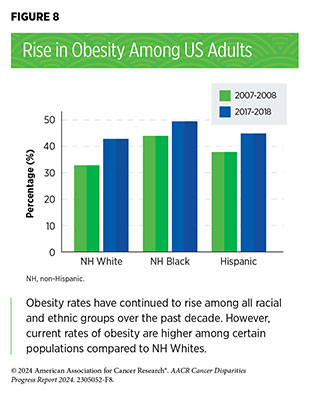

Among US adults, the rate of obesity was 41.9 percent from 2017 to 2020 (344)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . This is a 37 percent increase from the year 2000, when the rate was 30.5 percent (344)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . During the same time, severe obesity among US adults nearly doubled, with an increase from 4.7 percent to 9.1 percent (344)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The rise in obesity rates has been observed in most racial and ethnic groups (see Figure 8). As with smoking, adults who are obese have a higher risk of many chronic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer (289)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2022. Accessed: July 5, 2023. .

Of increasing concern is the rise in obesity among children and teens (2 to 19 years of age), rising 300 percent in the past five decades, from 5 percent in the 1970s to approximately 19.7 percent during the period from 2017 to 2020 (346)National Health Statistics Reports. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Recent data show that being overweight or obese during childhood increases the likelihood of developing cancer as adults (347)Jensen BW, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As in adults, racial and ethnic minority children have higher rates of obesity, with 26.2 percent of Hispanic and 24.8 percent of NH Black children being obese compared to 16.6 percent of NH White children between 2017 and 2020 (348)National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. In: National Center for Health S, editor. National Health Statistics Reports, NHSR No. 158. Hyattsville, MD; 2021. .

Concurrent with the rise in obesity, there has been a rise in obesity-related cancers in the United States (349)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity: Data, Trends, and Maps. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Almost one-tenth of cancers in the United States can be attributed to obesity (350)Pati S, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 485. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Increasing incidence of a subset of obesity-related cancers including kidney, pancreatic, gallbladder, endometrium, and colon or rectum, as well as multiple myeloma, has been more prominent in young adults (25 to 39 years of age) compared to adults 50 years of age or older (351)Sung H, et al. (2019) Lancet Public Health, 4: e137. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In young women, rates of obesity-associated cancers are increasing the most among Hispanic women when compared to NH Black and NH White women (132)Cotangco KR, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

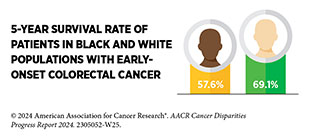

Early-onset cancers are also rising globally, with a striking 79 percent increase in new cases of cancer among individuals under 50 over the past 30 years (352)Zhao J, et al. (2023) BMJ Oncology, 2: e000049. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is estimated that in the next 10 years, 25 percent of rectal cancers and 11 percent of colorectal cancers will be diagnosed in individuals younger than 50 (353)Ullah F, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 3202. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Being overweight or obese increases the likelihood of developing early-onset colorectal cancer by 1.2 and 1.5 times, respectively, compared to maintaining a healthy weight (354)Hua H, et al. (2023) Front Oncol, 13: 1132306. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Weight loss interventions have proven to be effective in reducing or eliminating the risk of cancers associated with obesity (356)Schauer DP, et al. (2017) Obesity (Silver Spring), 25 Suppl 2: S52. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](357)Bruno DS, et al. (2020) Ann Transl Med, 8: S13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Barriers exist in attaining weight loss among certain racial and ethnic minority groups. When participants in weight loss programs are not engaged, it leads to nonadherence and unsuccessful outcomes (358)Newton RL, Jr., et al. (2024) Obesity (Silver Spring), 32: 476. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Structural barriers including long work and commute hours, inconvenient class times and locations, and limited disposable income for weight loss activities result in disparities in the ability of Hispanic and NH Black people to lose weight (359)Saju R, et al. (2022) J Gen Intern Med, 37: 3715. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Bariatric surgery, a term used to describe a collection of procedures that are done to help people who are obese lose weight, has been shown to lower the risk of developing and/ or dying from certain obesity-associated cancers (360)Adams TD, et al. (2023) Obesity (Silver Spring), 31: 574. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](361)Aminian A, et al. (2022) JAMA, 327: 2423. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, it is important to note that compared to White patients, Black patients experience higher adverse events 30 days following surgery, including postoperative mortality, morbidity, readmission, and reoperation (362)Stone G, et al. (2022) Am J Surg, 223: 863. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Eliminating disparities in obesity and obesity-related cancers necessitates further research to identify culturally tailored, community-based interventions that are scalable across settings including limited resource settings. Research shows that positive community support, more flexible or convenient work schedules, and low- or no-cost lifestyle resources such as gym memberships or one-on-one consultations can help reduce obesity among underserved groups (359)Saju R, et al. (2022) J Gen Intern Med, 37: 3715. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For example, Black women who participated in a 6 month weight loss program that was followed by a patient-centered, culturally sensitive weight loss maintenance intervention continued to lose weight compared to those who participated in a standard weight loss maintenance intervention (363)Tucker CM, et al. (2022) Clin Obes, 12: e12553. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Diet

Complex and interrelated factors ranging from socioeconomic, environmental, and biological to individual lifestyle factors contribute to obesity. There is, however, sufficient evidence that consumption of high-calorie, energy-dense foods and beverages and insufficient physical activity play a significant role. Poor diet, consisting of processed foods and lacking fresh fruits or vegetables, is responsible for the development of about 5 percent of all cancers, with several studies demonstrating a link between consumption of highly processed foods and cancer incidence (364)Morales-Berstein F, et al. (2024) Eur J Nutr, 63: 377. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](365)Jin Q, et al. (2023) Br J Cancer, 129: 1978. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](366)Chang K, et al. (2023) EClinicalMedicine, 56: 101840. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Conversely, consumption of a diet rich in fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, whole grains, and fish can help lower the risk of developing certain cancers and many other chronic conditions. One study of nearly 80,000 men from diverse backgrounds found that adherence to a healthy diet lowered risk for certain types of colorectal cancers (367)Hang D, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 155. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

It is concerning that US adults consumed 7 percent more highly processed foods in 2017–2018 than they did in 2001–2002 (368)National Center for Health Services. Fast food consumption among adults in the United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 322. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Consumption of fast food—food that can be prepared quickly and easily and is sold in restaurants and snack bars—is higher among racial or ethnic minority individuals, with 43 percent of NH Black adults versus 36 percent of NH White adults consuming fast food between 2013 and 2016, the most recent timeframe for which these data are available (368)National Center for Health Services. Fast food consumption among adults in the United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 322. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Disparities in diet quality among different segments of the US population can be attributed to socioeconomic and geographic factors, which contribute to food insecurity. As defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), food insecurity is the lack of access by all people in a household at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. Studies show that food insecurity is higher among racial or ethnic minorities and those who live in poverty (370)Taylor LC, et al. (2023) Med Res Arch, 11: DOI:10.18103/mra. v11i12.4593. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These communities are often located in neighborhoods considered “food deserts,” which are areas that have low availability of healthy foods like fresh fruit and vegetables and an abundance of fast-food options. Community-driven initiatives administered through key partners, such as faith-based organizations, schools, and local food retailers, are one mechanism to promote healthy eating among underserved populations.

Sugar-sweetened beverages are a major contributor to caloric intake among US youth and adults, and there are emerging data indicating that consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages may be associated with an increased risk of cancer (189)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2021. Accessed: June 30, 2023. (371)Zhao L, et al. (2023) JAMA, 330: 537. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In certain rural areas—for example, the Appalachia region—local interventions have led to a reduction in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and increased consumption of vegetables (372)Norman-Burgdolf H, et al. (2021) Prev Med Rep, 24: 101642. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The Philadelphia Beverage Tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, implemented in 2017, increased the cost by 1.5 cents per ounce of sodas and juices that contain sugar. The tax led to significant reductions in the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (373)Hua SV, et al. (2023) Jama Network Open, 6: e2323200. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](374)Kaplan S, et al. (2024) JAMA Health Forum, 5: e234737. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], with one study indicating as much as a 42 percent drop in the sale of these types of beverages after 2 years (375)Bleich SN, et al. (2021) JAMA Netw Open, 4: e2113527. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The tax revenue generated is used to fund early-education programs (including free universal pre-K), healthy messaging, and upgrades to playground equipment. Pilot initiatives like these are a step in the right direction and continuous evaluation will further determine their long-term health benefits and impact on diet, obesity, and cancer burden.

Physical Activity

Engaging in regular physical activity can reduce the risk of nine different types of cancer, with research indicating that over 46,000 US cancer cases annually could potentially be avoided if everyone met the recommended CDC guidelines for physical activity (see Sidebar 16) (376)Lopez-Bueno R, et al. (2023) JAMA Intern Med, 183: 982. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](377)Minihan AK, et al. (2022) Med Sci Sports Exerc, 54: 417. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. People who engage in 4 to 5 minutes of vigorous physical activity daily can reduce their cancer risk by up to 32 percent (378)Stamatakis E, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 1255. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are many barriers that may prevent individuals from being physically active, including cost and access to fitness facilities, low neighborhood walkability, lack of green spaces, inadequate tree canopy cover, and family obligations (380)Withall J, et al. (2011) BMC Public Health, 11: 507. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](381)Patel NA, et al. (2022) Kans J Med, 15: 267. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](382)Engelberg JK, et al. (2016) BMC Public Health, 16: 395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](383)Thornton CM, et al. (2016) SSM Popul Health, 2: 206. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These barriers are exacerbated in racial and ethnic minority individuals and medically underserved populations (see Figure 3). Based on recent data, physical inactivity is higher among Hispanic (31.7 percent) and NH Black (30.3 percent) populations, compared to those who are NH White (23.4 percent) (384)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Inactivity is More Common among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in Most States. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . There are also geographic disparities, with only 16 percent of people in suburban and rural areas meeting the recommended physical activity guidelines, compared to 27.8 percent of those living in urban areas (385)Abildso CG, et al. (2023) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 72: 85. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Alcohol Consumption

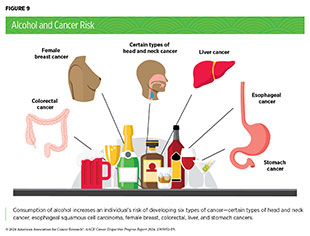

Alcohol consumption increases the risk for six different types of cancer (see Figure 9) and is linked to more than 200 diseases. Nearly 4 percent of cancers diagnosed worldwide in 2020 were attributed to alcohol consumption and in the United States, it is estimated that from 2013 to 2016, 75,000 cancer cases and 19,000 cancer deaths were linked to alcohol (386)Rumgay H, et al. (2021) Lancet Oncol, 22: 1071. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](387)Goding Sauer A, et al. (2021) Cancer Epidemiol, 71: 101893. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are sociodemographic disparities in consumption of alcohol.

The greatest risks are associated with long-term alcohol consumption and binge-drinking, i.e., when large amounts of alcohol are consumed in a short period of time (389)White AJ, et al. (2017) Am J Epidemiol, 186: 541. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Even light intake of alcohol can increase an individual’s risk for certain cancers, while moderate drinking can increase the risk of developing certain cancers of the head and neck, breast, and colon and rectum (390)Cao Y, et al. (2015) BMJ, 351: h4238. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](391)Choi YJ, et al. (2018) Cancer Res Treat, 50: 474. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](392)Yoo JE, et al. (2021) JAMA Netw Open, 4: e2120382. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Those who experience structural racism consume more alcohol. As one example, a recent study found that structural racism experienced by Black individuals increased the level of binge drinking frequency and smoking (393). Increasingly, studies show that exposure to or lived experiences with racism, micro-aggressive behavior, and stress leads to an increase in levels of alcohol consumption (393)Woodard N, et al. (2024) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 33: 261. (394)Desalu JM, et al. (2019) Addiction,114: 957. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](395)Buckner JD, et al. (2023) J Racial Ethn Health Disp, 10: 987. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

UV Exposure

UV radiation is a type of light emitted primarily from the sun but also from artificial sources, such as tanning beds. Exposure to UV radiation can lead to the development of skin cancers, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma, which is the most aggressive form of skin cancer. In fact, UV radiation accounts for 95 percent of skin melanomas and 6 percent of all cancers (342)Islami F, et al. (2018) CA Cancer J Clin, 68: 31. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This is because UV radiation can damage cellular DNA, with continued exposure leading to cancer. In the United States, 33,000 sunburns requiring emergency room visits are reported annually. Past sunburns are a strong predictor of future skin cancer, especially melanoma. One study reported that women who experienced at least five episodes of severe sunburns between the ages of 15 and 20 years were 80 percent more likely to develop melanoma later in life, compared to those who did not experience sunburns (397)Wu S, et al. (2014) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 23: 1080. .

While those who are light skinned are more susceptible to sunburn, those with darker skin are also at risk. Black and Hispanic individuals, who typically have darker skin tones compared to NH White individuals, are less likely to engage in sun-safe habits, such as wearing long sleeves, seeking shade, and using sunscreen while outdoors (398)Calderon TA, et al. (2019) Prev Med Rep, 13: 346. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These behaviors are attributable to lack of information and education on how sunburn increases the risk of skin cancer. In a survey of high school students in Texas, those from racial minority populations, and individuals of low socioeconomic status, showed poorer knowledge of melanoma and skin cancer risk (399)Zamil DH, et al. (2023) Dermatol Pract Concept, 13: e2023014. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These groups are also less knowledgeable about the appearance of melanoma, understanding the importance of skin self-examinations, and less likely to be examined for skin lesions by a doctor (400)Harvey VM, et al. (2014) Cancer Control, 21: 343. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Exacerbating the lack of knowledge about skin cancer risk are “sunscreen deserts,” which are areas that have lower availability and lesser variety of sunscreen compared to other areas. One study found that sunscreen deserts were more prominent in majority Black areas compared to majority White areas (401)Onamusi TA, et al. (2023) Arch Dermatol Res, 316: 32. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The disparity in skin cancer preventive behavior is of public health concern because Black, Hispanic, and NHOPI people tend to be diagnosed at more advanced stages despite having a lower incidence of skin cancer (402)Qian Y, et al. (2021) J Am Acad Dermatol, 84: 1585. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](403)Kim DY, et al. (2024) J Am Acad Dermatol, 90: 623. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Patients from racial and ethnic minority populations also have distinct characteristics of skin cancer, differing clinical features, and unique genetic risk factors compared to NH White patients (404)Blumenthal LY, et al. (2022) J Am Acad Dermatol, 86: 353. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](405)Kolla AM, et al. (2022) J Am Acad Dermatol, 87: 1220. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

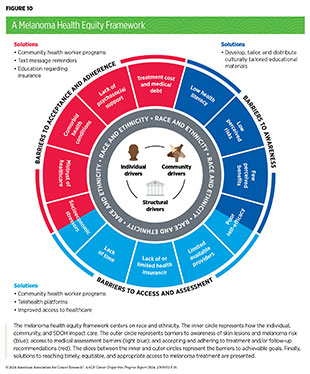

To address the disparities in skin cancer risk among racial and ethnic minority populations, developing a health equity framework for dermatologists and other constituents in the public health sector has been proposed (405)Kolla AM, et al. (2022) J Am Acad Dermatol, 87: 1220. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This framework addresses several barriers, including appropriate medical assessment, awareness concerning skin lesions and melanoma risk, and acceptance and adherence to treatment and/or follow-up recommendations (see Figure 10).

Indoor tanning exposes individuals to the same harmful UV radiation of the sun but in an artificial setting. Fortunately, rates of indoor tanning have been declining over the past decade, particularly among US youth (406)Holman DM, et al. (2019) Journal of Community Health, 44: 1086. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Currently, 44 states and the District of Columbia either ban or regulate the use of indoor tanning devices by minors (407)Skin Cancer Foundation. Indoor Tanning Legislation: Here’s Where We Stand. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . All states should enact legislation banning indoor tanning for minors, to continue the downward trend of tanning bed usage, especially among youth.

Infectious Agents

Cancer-causing agents or pathogens (bacteria, viruses, and parasites) increase a person’s risk for several types of cancer. Infection with these agents can change the way a cell behaves, weaken the immune system, and cause chronic inflammation, all of which can lead to cancer. In the United States about 3 percent of all cancer cases can be attributed to infection with pathogens (342)Islami F, et al. (2018) CA Cancer J Clin, 68: 31. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Globally, an estimated 13 percent (2.2 million) of all cancer cases in 2018 were attributable to pathogenic infections, with more than 90 percent of these cases caused by four pathogens: human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) (409)de Martel C, et al. (2020) Lancet Glob Health, 8: e180. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV is a group of more than 200 related viruses that are responsible for almost all cervical cancers, 90 percent of anal cancers, and 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancers, as well as most penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancers. While most HPV infections do not cause cancer, those that are persistent and with high-risk strains of HPV can lead to cancer. These high-risk HPVs cause 2 percent and 3 percent of all cancers in men and women, respectively, in the United States. Globally, HPV-related cancers make up about 5 percent of all cancers (410)National Cancer Institute. HPV and Cancer. Accessed: August 11, 2022. .

Incidence of HPV is higher among certain racial and ethnic minority populations. Rates of HPV infection are higher in young Black women compared to young White women (411)Hirth J (2019) Hum Vaccin Immunother, 15: 146. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Gay and bisexual men and men who have sex with men are twice as likely to have anal HPV infection compared to men who have sex with women due to lower rates of contraceptive use during intercourse (412)Wei F, et al. (2021) Lancet HIV, 8: e531. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](413)Chambers C, et al. (2023) J Infect Dis. 228: 89. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The higher rate of HPV infection among gay and bisexual men may partly explain why this population is 17 times more likely to develop anal cancer compared to heterosexual men (414)Chidobem I, et al. (2022) Vaccines (Basel), 10: 604. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

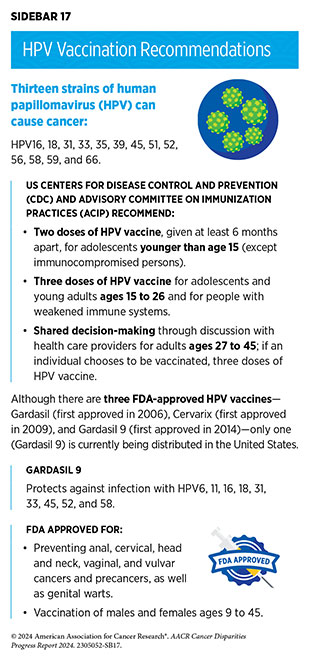

The HPV vaccine is approved for males and females ages 9 to 45, with recommendations for the first doses beginning at age 11 to 12 (see Sidebar 17). There are 13 different types of HPV that can cause cancers; the HPV vaccine currently used in the United States, Gardasil 9, can protect against nine of these HPV strains.

Despite the clear evidence of the HPV vaccine reducing cervical cancer incidence, the uptake of the HPV vaccine has been suboptimal in the United States (415)Mix JM, et al. (2021) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 30: 30. . This stands in stark contrast to other countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia, which have very high rates of vaccination among adolescents and young adults. The United States does not require HPV vaccination to attend school. In 2021, 76.9 percent of adolescents ages 13 to 17 had received one dose of the HPV vaccine and only 61.7 percent had received the recommended two doses (416)Pingali C, et al. (2022) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 71: 1101. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While initial uptake of the HPV vaccine was extremely low among racial and ethnic minority populations, there have been significant improvements in the past decade, especially among Black adolescent girls. Disparities still exist, however, due to location, income level, and by educational attainment (411)Hirth J (2019) Hum Vaccin Immunother, 15: 146. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](417)Stephens ES, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2343325. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](418)Castaneda-Avila MA, et al. (2022) Hum Vaccin Immunother, 18: 2077065. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

HPV vaccination for gay and bisexual men has been low among those eligible, with an estimated 63 percent of gay and bisexual men ages 18 to 26 having received any dose of the HPV vaccine (419)Nadarzynski T, et al. (2021) Vaccine, 39: 3565. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The lack of HPV vaccination awareness can be explained by a lack of education and trust (i.e., “vaccine hesitancy”) (420)Klassen AC, et al. (2024) Vaccine, 42: 1704. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](421)Boucher JC, et al. (2023) BMC Public Health, 23: 694. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] about the importance of HPV vaccination and the risk of cancer from HPV infection (422)Alhazmi H, et al. (2024) J Immigr Minor Health, 26: 117. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In a study of over 15,000 people, only 40.4 percent of those with less than a high school diploma, compared to 78.2 percent with a college degree or higher, had awareness of how vaccination against HPV would reduce HPV infection (417)Stephens ES, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2343325. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Among those with HPV awareness, only 51.7 percent of those with less than a high school diploma knew that HPV causes cervical cancer, compared to 84.7 percent of adults with a college degree or higher (417)Stephens ES, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2343325. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Developing evidence-based strategies to improve HPV vaccination uptake among all eligible individuals could have immense public health benefits.

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

Chronic infection from HBV and HCV can cause liver cancer and can be a risk factor for other malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Globally, the most common risk factor for liver cancer is chronic infection with HBV and HCV. In the United States, after new reported cases of HBV remained stable from 2013 through 2019, there was an abrupt decrease of 32 percent in reported cases in 2020, with a further decrease of 14 percent between 2020 and 2021 (423)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Hepatitis B. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. Accessed: March 26, 2024. . These decreases are potentially attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have led to reduced testing but not necessarily reduced infections (423)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020 Hepatitis B. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. Accessed: March 26, 2024. . In contrast, cases of acute HCV have doubled during 2013–2020, with an increase of 7 percent between 2020 and 2021 (424)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. Accessed: March 26, 2024. .

Rates of HBV infection are highest among NH Asian adults (21.1 percent) and NH Black adults (10.8 percent) compared to White adults (2.1 percent) (425)National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence and trends in hepatitis B virus infection in the United States, 2015–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 361. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Additionally, there are disparities based on place of birth: 11.9 percent of adults born outside the United States have past or present HBV infection compared to 2.5 percent of those born in the United States (425)National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence and trends in hepatitis B virus infection in the United States, 2015–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 361. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Recent estimates show that HBV infections are likely higher than the 1.8 million as reported in 2020 because of imprecise tracking of infections in immigrant populations. Appropriate tracking of HBV infections is important to predict future incidence of liver cancer, which is expected to increase by 31 percent in the United States from 2019 to 2030 (426)Razavi-Shearer D, et al. (2023) Lancet Reg Health Am, 22: 100516. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Compared to all other racial and ethnic groups, acute HCV infection is highest among AI/AN individuals, with 2.7 cases of HCV reported per 100,000 in 2021, the most recent year for which such data are available. The rate of newly reported chronic HCV cases was also highest among AI/AN persons compared to all other groups, with 68.9 cases per 100,000 population reported in 2021 (427)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance National Profile of Viral Hepatitis. Accessed:March 17, 2024. . To reduce the burden of HCV, the Indian Health Service recommends universal screening of all AI/AN adults (428)Indian Health Service. Hepatitis C: Universal Screening and Treatment. Accessed: March 26, 2024. . Further, to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat, US HHS department released the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021–2025) in 2022. The primary goals are to prevent new infections, improve health outcomes for infected individuals, reduce disparities and health inequities, increase surveillance, and bring together all relevant constituents in coordinating efforts to address the hepatitis epidemic.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

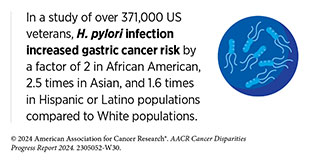

H. pylori is a type of bacteria that has been shown to cause gastric cancer if left untreated. Among those diagnosed with H. pylori infection, racial and ethnic minority populations (429)Garman KS, et al. (2024) Gastric Cancer, 27: 28. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] and those who smoked (430)Kumar S, et al. (2020) Gastroenterology, 158: 527. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] were at a greater risk of gastric cancer. Fortunately, treatment of H. pylori infection decreases gastric cancer risk (430)Kumar S, et al. (2020) Gastroenterology, 158: 527. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Overall, H. pylori–associated gastric cancer has declined over the past two decades; however, rates of H. pylori–associated gastric cancer are not equal among all population groups (431)Lai Y, et al. (2022) Front Public Health, 10: 1056157. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Infection with H. pylori is higher among AI/AN communities. Among Navajo adults in Arizona, the H. pylori prevalence is 62 percent, while 75 percent of the Alaska Native population are reportedly infected with H. pylori, compared to 36 percent in the overall US population (432)Monroy FP, et al. (2022) Diseases, 10: 19. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](433)Nolen LD, et al. (2018) Int J Circumpolar Health, 77: 1510715. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](434)Shah S, et al. (2023) Sci Rep, 13: 1375. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This high incidence may explain why AI/AN populations experience higher rates of gastric cancer compared to the White population (435)Cordova-Marks FM, et al. (2022) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The causes of high rates of infection are multifactorial and include genetics, environmental factors, and socioeconomic factors (436)Harris RB, et al. (2022) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19: 797. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While living conditions in the Navajo Nation have improved over the past decades, crowded and substandard housing, which relies on untreated well water, increases the likelihood of H. pylori transmission and infection (437)Rolle-Kampczyk UE, et al. (2004) Int J Hyg Environ Health, 207: 363. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Environmental Exposures

Built environment describes the physical environment of a neighborhood in which people live, and includes transportation, infrastructure, clear air, buildings that abide by radon regulations and asbestos abatement procedures, clean water, healthy food access, community gardens, walkability, public services, and policies and regulations (see Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities). Environmental exposures are the substances people encounter in their built environment or occupations, including sunlight, chemical pollutants, social interactions, and/or stress, which can impact human health.

In this section, we focus on the physical environment and highlight the disparities in exposure to toxic substances, such as environmental carcinogens, which are also associated with increased risk for cancer and poorer cancer outcomes. It can be difficult for people to avoid or reduce their exposure to environmental carcinogens because modifying the amounts of most environmental exposures requires regulation by local, state, or national bodies.

Exposure to higher than acceptable levels of certain pollutants, without appropriate protection, can increase the risk of certain diseases. Environmental carcinogens, which are substances that can lead to cancer and are present in the environment, include arsenic, asbestos, radon, lead, radiation, and other chemical pollutants including heavy metals and endocrine disrupting chemicals. Coordinated efforts such as those being initiated by Cohorts for Environmental Exposures and Cancer Risks (CEECR) build collaborative infrastructure and facilitate integrated scientific research for enhancing the understanding of environmental exposures influencing cancer etiology, and the genetic, behavioral, and structural factors that modify risk across diverse populations.

Of increasing concern among public health experts is climate change, which refers to a change in temperature and weather patterns across the globe directly attributable to human activity. There is strong scientific evidence for climate change, which has the potential to worsen human exposure to carcinogens. For instance, wildfires in the western United States and Canada, which have increased in intensity in recent years due to climate change (438)US Global Change Research Program. Fourth National Climate Assessment. Volume II: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , have led to increased exposure to certain metal toxins, such as carcinogenic forms of chromium, known to increase cancer risk (439)Lopez AM, et al. (2023) Nat Commun, 14: 8007. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Those living in rural communities or those who participate in firefighting activities may be at a higher risk of developing cancer as climate change continues to increase wildfire intensity.

Radon

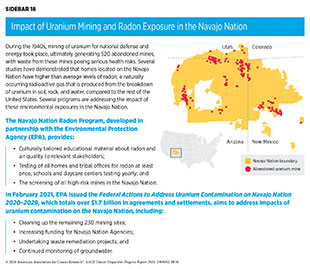

Radon, a naturally occurring radioactive gas that is produced from the breakdown of uranium in soil, rock, and water, is the second leading cause of lung cancer death in the United States. Although levels of naturally occurring radon vary widely based on geographic location, certain populations, such as the Navajo Nation, are situated on land rich in radioactive ores containing uranium (see Sidebar 18).

Pollutants and Endocrine-disrupting Chemicals

Living near industrial areas can increase exposure to toxic chemicals and metals. Most industries are usually adjacent to neighborhoods with low SES and with a high proportion of racially and ethnically minoritized populations (442)Collins MB, et al. (2016) Environ Res Lett, 11: 015004. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](443)Johnston J, et al. (2020) Curr Environ Health Rep, 7: 48. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These exposures can increase the risk for certain types of cancer, such as hematologic malignancies and thyroid, lung, breast, and uterine cancers (444)Jephcote C, et al. (2020) Environ Health, 19: 53. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](445)van Gerwen M, et al. (2023) EBioMedicine, 97: 104831. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](446)Liu H, et al. (2023) Front Oncol, 13: 1282651. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](447)Cheng I, et al. (2022) Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 206: 1008. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](448)Carroll R, et al. (2023) Environ Res, 239: 117349. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The endocrine system is made up of the glands and organs that make hormones and release them directly into the blood so they can travel to, and regulate functions of, body tissues and organs. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals can be natural or human-made, and may mimic, block, or interfere with the body’s hormones. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals, such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), have been shown to increase the risk of certain cancers, such as thyroid and breast cancers (445)van Gerwen M, et al. (2023) EBioMedicine, 97: 104831. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](446)Liu H, et al. (2023) Front Oncol, 13: 1282651. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. An emerging concern is the use of personal care products such as hair straightening products, which contain hazardous chemicals with hormone-disrupting properties and have been shown to increase the risk of uterine cancers (449)Chang CJ, et al. (2022) J Natl Cancer Inst, 114: 1636. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The use of chemical hair relaxers among Black women is shown to increase the risk of uterine cancer in postmenopausal women (450)Bertrand KA, et al. (2023) Environ Res, 239: 117228. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The use of hair dye, relaxers, and other hair products have also been shown to be associated with breast cancer risk (451)Llanos AAM, et al. (2017) Carcinogenesis, 38: 883. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

PFAS as well as other contaminants including asbestos, arsenic, radon, agricultural chemicals, and hazardous waste can be present in drinking water (452)Morris RD (1995) Environ Health Perspect, 103 Suppl 8: 225. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. AI/AN individuals are 19 times more likely than White individuals to live in a household without indoor plumbing, requiring them to source water from communal wells (453)VanDerslice J (2011) Am J Public Health, 101 Suppl 1: S109. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](454)Tanana H, et al. (2021) Health Secur, 19: S78. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These water sources are more prone to being contaminated with bacteria, arsenic, and uranium (436)Harris RB, et al. (2022) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19: 797. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](454)Tanana H, et al. (2021) Health Secur, 19: S78. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], all of which increase the risk of several types of cancer including gastric, liver, lung, bladder, and kidney cancer (436)Harris RB, et al. (2022) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 19: 797. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](452)Morris RD (1995) Environ Health Perspect, 103 Suppl 8: 225. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](455)Wroblewski LE, et al. (2010) Clin Microbiol Rev, 23: 713. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Studies have also found that community water systems contaminated with PFAS are more likely to provide water to communities with greater proportions of Latino and NH Black populations (456)Liddie JM, et al. (2023) Environ Sci Tech, 57: 7902. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Evidence demonstrates that exposure to PFAS pollution is linked to these communities’ proximity to polluting industries such as airports, industrial sites, wastewater treatment plants, and military fire training areas (456)Liddie JM, et al. (2023) Environ Sci Tech, 57: 7902. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the specialized cancer agency of the World Health Organization (WHO), classifies outdoor air pollution as a potential cause of cancer in humans (457)Loomis D, et al. (2013) Lancet Oncol, 14: 1262. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One type of air pollution is called particle pollution, which refers to a mix of tiny solid and liquid particles that are in the air. In 2013, IARC concluded that particle pollution may cause lung cancer (458)American Lung Association. State of the Air 2023. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . Air pollution also contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) which have been associated with a number of cancers including cancers of the lung and breast (459)Shen J, et al. (2017) Br J Cancer, 116: 1229. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](460)Korsh J, et al. (2015) Breast Care (Basel), 10: 316. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In 2023, 119.6 million people lived in places with unhealthy levels of particulate pollution and 63.7 million people living in the United States were exposed to daily, unhealthy spikes in particle pollution (461)American Lung Association. State of the Air 2023 Report. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Low-income populations and minority groups are among those who often face higher exposure to pollutants (462)Bradley AC, et al. (2024) Environ Sci Technol, DOI: 10.1021/acs. est.3c03230.. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](463)Tessum CW, et al. (2021) Sci Adv, 7: eabf4491. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Those who live in urban areas, particularly with low socioeconomic status, are exposed to higher levels of certain traffic-related air pollution risks, which have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of lung cancer (447)Cheng I, et al. (2022) Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 206: 1008. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](448)Carroll R, et al. (2023) Environ Res, 239: 117349. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Occupational Exposures

Higher than normal levels of exposure to carcinogens have led IARC to classify certain occupations, such as firefighting and industrial painting, and work environments, such as iron and steel foundries or working around welding fumes, as class 1 carcinogens, meaning they are cancer-causing to humans.

Racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to work in jobs that have high levels of exposure to carcinogenic chemicals (464)Bonner SN, et al. (2024) JAMA Oncol, 10: 122. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One study found that among roofers and welders, who can be exposed to carcinogenic fumes, those who were African American had increased risk of adenocarcinoma and large cell lung cancer compared to other races and ethnicities (465)Calvert GM, et al. (2012) Am J Ind Med, 55: 412. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. African American workers also have increased occupational exposures to silica and asbestos compared to White individuals, which can increase the risk of lung cancer (296)Juon HS, et al. (2021) Prev Med, 143: 106355. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Mexican American individuals are more than twice as likely to develop lung cancer caused by conventional and antimicrobial pesticide exposure compared to other groups, attributable to their employment in agricultural occupations (466)McHugh MK, et al. (2010) Cancer Causes Control, 21: 2157. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](467)Ashing KT, et al. (2022) JCO Oncol Pract, 18: 15. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Studies show that firefighters are also at increased risk of multiple types of cancer because of exposure to smoke and other hazardous materials (see Sidebar 19). Of interest, Hispanic and Black firefighters are at higher risk to develop these cancers compared to their White counterparts (468)Tsai RJ, et al. (2015) Am J Ind Med, 58: 715. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](469)Goodrich JM, et al. (2021) Epigenet Insights, 14:25168657211006159. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Other risk factors associated with a person’s occupation, including lack of sleep and night-shift work, have also been shown to increase their risk of developing certain types of cancers. CDC reports that about 11 million adults in the United States frequently work night shifts, with certain groups, such as men, and Black and non-Hispanic individuals, more likely to do this type of work. In one recent study, researchers found that women age 50 or older who worked both day and night shifts were twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who only worked day shifts (478)IARC Working Group on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. Night Shift Work. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Although the underlying mechanisms are not clear, researchers believe that disruption of the body’s circadian rhythm (i.e., the internal clock) can alter biological processes that normally help prevent cancer development (479)Huang C, et al. (2023) Cancer Biol Med, 20: 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Emerging research indicates that avoiding lighting that disrupts circadian rhythms, for example, lighting that is low in blue light, may help reduce cancer risk (480)Sahin L, et al. (2022) LR & T, 54: 441. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](481)Figueiro MG, et al. (2010) Int J Endocrinol, 2010: 829351. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](482)Faraut B, et al. (2019) Front Neurosci, 13: 1366. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Long-term research is needed to understand how avoiding exposure to certain light sources, particularly at night, may help regulate the circadian rhythms and thus may reduce cancer risk.

Social and Behavioral Stress

Stress-inducing social and behavioral factors have been considered as possible cancer risk factors. Several studies link elevated psychosocial stress with biological changes associated with cancer such as increased epigenetic aging, which are reversible changes to the DNA and RNA (483)Skinner HG, et al. (2024) J Am Geriatr Soc, 72: 349. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](484)Lawrence WR, et al. (2023) Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 16: 259. . This is concerning because it has been reported that patients with cancer from racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to report psychosocial stress compared to those who are White (485)Sanchez-Diaz CT, et al. (2021) Cancer Causes Control, 32: 357. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](486)Mazor M, et al. (2021) Psychooncology, 30: 1789. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](487)Garrett E, et al. (2024) J Natl Cancer Inst, 116: 258. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

One area of active investigation in cancer disparities research is understanding the contribution of the allostatic load—the combined influences of stresses, lifestyle, and environmental exposures—on the lifetime risk of cancer and other diseases (488)Obeng-Gyasi S, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2313989. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](489)Guan Y, et al. (2023) Breast Cancer Res, 25: 155. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](490)Obeng-Gyasi S, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2221626. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](491)Parker HW, et al. (2022) Am J Prev Med, 63: 131. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Heightened allostatic load due to stressors related to SDOH (see Figure 3) is linked to worse cancer outcomes, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities and medically underserved populations (492)Li C, et al. (2023) BMC Womens Health, 23: 448. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](493)Moore JX, et al. (2022) SSM Popul Health, 19: 101185. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers are evaluating interventions, including lifestyle factors, that may alleviate allostatic load in populations that are at an increased risk for cancer.

Next Section: Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection Previous Section: Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Disparities