- The State of US Cancer Disparities in 2024

- Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities

- Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Health Disparities

- Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors

- Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection

- Disparities in Clinical Research and Cancer Treatment

- Disparities in Cancer Survivorship

- Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce

- Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Science-based Public Policy

- AACR Call to Action

Executive Summary

This is an exciting time in cancer science and medicine. Thanks to research, we are making unprecedented progress against the many diseases we call cancer. However, these advances have not benefited everyone equally. Because of a long history of structural inequities and systemic injustices in the United States, many segments of the US population continue to shoulder a disproportionate burden of cancer. Disparities in health care are among the most significant forms of inequity and injustice, and it is imperative that everyone plays a role in eliminating the barriers to health equity, which is one of the most basic human rights.

As the first and largest professional organization in the world dedicated to preventing and curing all cancers for all populations, the American Association for Cancer Research® (AACR) is committed to accelerating the pace of research to address the disparities across the cancer continuum. AACR is also dedicated to increasing public awareness of cancer disparities and underscoring the importance of cancer disparities research in saving lives, as well as to advocating for increased annual federal funding for the government entities that fuel progress against cancer disparities, in particular, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024 to Congress and the American public is a cornerstone of AACR’s educational and advocacy efforts to achieve health equity. This report highlights areas of recent progress in reducing cancer disparities. It also emphasizes the vital need for continued transformative research and for increased collaborations to ensure that research-driven advances benefit all people, regardless of their race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or geographic location.

The State of US Cancer Disparities in 2024

Even though we are making great progress against cancer in the United States, as illustrated by the declining overall cancer death rate and the increasing number of cancer survivors, it is projected that there will still be 2,001,140 new cases diagnosed in 2024 and 611,720 deaths from the disease. The burden of cancer is disproportionally higher among certain segments of the US population.

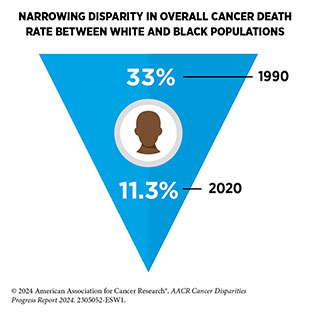

Racial and ethnic minority population groups in the United States have long experienced cancer disparities. Despite promising trends in narrowing disparities in some instances, cancer disparities remain a serious challenge to public health and a significant barrier to achieving health equity. As discussed in this report, compared to White people, incidence rates for colorectal and cervical cancers are higher among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people and for cervical cancer among Hispanic women. Compared to the White population, the overall cancer death rate is higher among Black and AI/AN populations. Furthermore, all racial and ethnic minority groups have a lower 5‐year relative survival compared to the White population. Other concerning trends include the increasing burden of certain cancers such as the rising incidence rates of cancer among adults younger than 50 years, also called early-onset cancers. Two examples of this trend include rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer in AI/AN people, and of lung cancer in Asian women who have never smoked.

In addition to racial and ethnic minority groups, many segments of the US population shoulder a disproportionate burden of cancer. These groups include rural residents, people living under poverty, and individuals who belong to sexual and gender minority (SGM) communities. The decline in the overall cancer death rates has been slower in rural residents compared to those living in urban counties. Counties with persistent poverty have a 7 percent higher death rate from all cancers combined compared to non-persistent poverty counties. Additionally, population-level cancer data on members of SGM communities are lacking, making it difficult to understand the true burden of cancer in this population.

It is increasingly evident that each of the US population groups is diverse, and collecting comprehensive, disaggregated cancer data for subgroups is critical to fully understand the extent of cancer disparities within and among these populations. As one example, combining Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) with Asian populations can hide significant cancer disparities experienced by the NHOPI population as well as by the Asian subgroups. The impact of cancer disparities is felt not only by the patient populations, but also by the US economy. The economic cost of racial and ethnic health disparities in 2018 alone was $451 billion, a majority of which was disproportionately borne by AI/ AN, Black, and NHOPI populations. As outlined in the AACR Call to Action, the bold vision of health equity can only be realized if the US Congress continues to provide sustained, robust, and predictable increases in funding for the federal agencies that are spearheading efforts to address and eliminate cancer disparities.

Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities

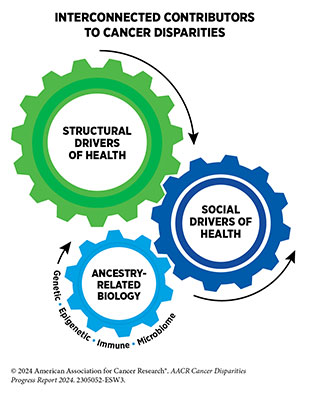

Health disparities, including cancer disparities, adversely impact racial and ethnic minorities and medically underserved populations. These disparities have stemmed from a long history of structural racism and contemporary injustices in the US and continue to have lasting, multigenerational adverse effects on marginalized populations in all aspects of life, including on health outcomes. Researchers have proposed many frameworks to understand and address influences that determine health outcomes and contribute to cancer disparities. These frameworks are based on a complex network of interrelated factors, called social drivers of health (SDOH), also referred to as social determinants of health.

According to NCI, SDOH are the social, economic, and physical conditions in the places where people are born and where they live, learn, work, play, and get older that can affect their health, well-being, and quality of life. Social drivers of health include factors such as education level; income; employment; housing; transportation; and access to healthy food, clean air, water, and health care services. The interplay between SDOH, biological, and environmental factors impacts all aspects of a person’s lived experiences, including health outcomes across the lifespan. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, digital health, and liquid biopsies, also have the potential to influence health outcomes, and inequitable utilization can drive cancer disparities.

Ongoing research is identifying the multilevel and multifaceted impacts of SDOH on the health of individuals, communities, and populations. It is increasingly evident that SDOH impact cancer incidence and outcomes. Thus, addressing SDOH can not only improve overall health, but also help reduce the cancer disparities which are deeply rooted in social and economic disadvantages experienced by racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations. Constituents across the continuum of cancer care are taking multipronged approaches to address SDOH at various levels, with the overarching goal of achieving health equity for everyone.

Evidence-based interventions and policies implemented at the population level have the potential to not only improve the nation’s health, but also strengthen the economy. The federal government has implemented numerous programs that are focused on providing stable and safe housing, nutrition and food access, and economic mobility. Similarly, NIH, NCI, CDC, and cancer-focused organizations are collaborating with each other and with institutes across the nation to investigate, develop, and implement interventions that are meaningful to the communities that they serve. Research has shown that racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations substantially benefit from community engagement and patient navigation that can enhance participation in healthy behaviors; increase adherence to cancer screening; and improve participation in clinical trials and receipt of treatment. Ongoing evaluation of the implemented strategies is essential to fully understand the impact of such efforts on addressing cancer disparities.

Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Disparities

Cancer is a collection of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell multiplication. Cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis—the spread of cancer cells from primary sites to distant organs—are all complex, multistep processes that are influenced by alterations both inside and outside the cell.

Cancer-driving changes inside the cell include alterations in the DNA, RNA, and/or protein. Research has also shown that tumor initiation and progression are largely dependent upon complex interactions between cancer cells and the surrounding tissue, known as the tumor microenvironment. Among the key components of the tumor microenvironment are immune cells and blood vessels. While immune cells can identify and eliminate cancer cells under normal circumstances, in many cases, the immune system is suppressed, permitting the formation and progression of tumors. The blood and lymphatic networks are the primary conduits for the process of metastasis. Additionally, emerging evidence indicates that the microbiome, which is the collection of all microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi) living in the body, can also influence cancer development.

Research has shown that there are ancestry-related differences in cancer-driving cellular and molecular alterations, such as those occurring in tumor and immune cells. Cancer disparities among racial and ethnic minority groups are driven by a complex interplay between structural and social drivers of health as well as biological factors that are attributable to ancestral differences between population groups. A major challenge in cancer science is the fact that most currently available data on cancer etiology are based on studies of individuals that are of European ancestry. Researchers are addressing this challenge through ongoing efforts to increase racial, ethnic, and ancestral diversity in cancer biology research investigations. Notably, biological differences among cancers in patients of different ancestries could provide novel targets for therapies and improve precision medicine.

Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors

Research in basic, translational, and population sciences has broadened our understanding of the factors that increase an individual’s risk of developing cancer. Modifiable risk factors, including tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, UV exposure, alcohol consumption, pathogenic infections, and obesity, contribute to 40 percent of all cancer cases. Because several of these risks can be modified, many cases of cancer could potentially be prevented.

Environmental risk factors, such as air pollution, water contamination, and naturally occurring radon gas, among others, can also increase a person’s risk of certain types of cancer. Furthermore, occupations such as firefighting and night shift work can expose individuals to factors that increase their cancer risk.

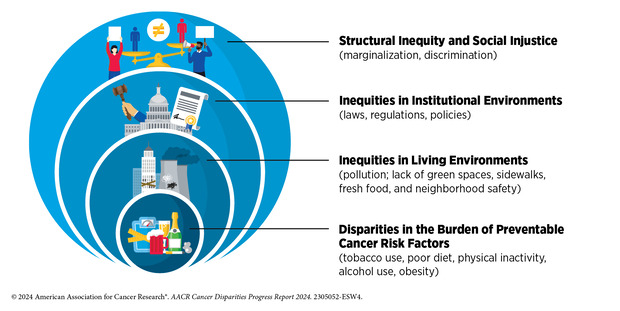

Individuals can reduce their risk of developing cancer through behavioral and lifestyle changes. However, long-standing inequities in numerous SDOH contribute to significant disparities in the prevalence of modifiable cancer risk factors among socially, economically, and geographically disadvantaged populations. These disparities stem from decades of structural, social, and institutional injustices, placing disadvantaged populations in unfavorable living environments that contribute to behaviors that increase cancer risk.

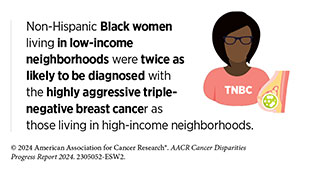

Individual behaviors are strongly influenced by the surrounding environment. Unfortunately, neighborhoods where socioeconomically disadvantaged populations reside are often characterized by low walkability, reduced availability of healthy food options, including fresh fruits and vegetables, and limited outdoor space for recreation and exercise. Socioeconomically vulnerable populations are also more likely to reside in less favorable locations such as near highways, near busy roads, or near industries, which increases their exposure to environmental pollutants to a greater degree, thereby increasing cancer risk. Additionally, occupations that increase exposure to cancer risk factors are also more likely to be staffed by minoritized populations.

Risk factors can intersect with other population characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability status among others, to drive cancer disparities. As one example, individuals with disabilities, who may have fewer occupational opportunities and lower income, also have higher prevalence of smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity. It is imperative that public health experts prioritize cancer prevention efforts that account for the complex and interrelated factors across institutional, social, and individual levels influencing personal risk exposure and disparate health outcomes. There is an urgent need for all members of the medical research community to come together and develop strategies that enhance the dissemination of our current knowledge of cancer risk reduction and implement evidence-based interventions for reducing the burden of cancer for everyone.

Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection

Cancer screening means finding precancerous lesions and cancers at their earliest stage when they are easier to treat and potentially curable. In the United States, government-affiliated agencies or other professional societies convene independent panels of experts in preventive medicine to develop population-level screening guidelines; the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is one such panel. USPSTF recommends screening for breast, prostate, cervical, and colorectal cancers for individuals who are at an average risk of being diagnosed with these cancer types. In addition, USPSTF also issues screening guidelines for individuals who are at an increased risk of being diagnosed with certain cancers, e.g., lung cancer screening guidelines for current or former smokers.

Many of the disparities in cancer screening experienced by racial and ethnic minority populations and medically underserved groups stem from systemic and structural barriers. For example, residents of low-income neighborhoods have less access to affordable and quality health care facilities that can perform cancer screening tests. Deeply rooted mistrust of the health care system, originating from a history of injustices committed by the health care establishment of the time, also contributes to cancer screening disparities. In some population groups, cultural beliefs, as well as lack of knowledge about cancer screening, play a role in exacerbating disparities in cancer screening. Another major source of disparities in cancer screening is barriers to follow-up exam(s) if the initial screening test indicates that the individual may have cancer. Further contributing to the disparities is the lack of participant diversity in the clinical studies that were used to develop the current cancer screening guidelines.

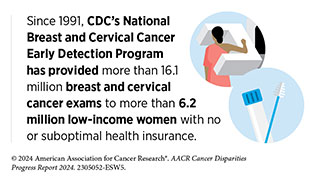

Researchers are taking multilevel approaches to address disparities in cancer screening and follow-up exams. Many of the approaches have been effective and provide a blueprint to effectively reach racially and ethnically minoritized communities and medically underserved populations. These strategies include developing comprehensive public health campaigns for eligible individuals to receive cancer screening; reducing mistrust in the health care systems; increasing access to health insurance to minimize out-of-pocket costs for certain types of screening tests; and developing culturally tailored interventions through patient navigation and community engagement.

Disparities in Clinical Research and Cancer Treatment

The dedicated efforts of individuals working in medical research are constantly translating new research discoveries into advances in cancer treatments that are improving survival and quality of life for people in the United States and around the world. Clinical trials are a vital part of medical research because they establish whether new cancer treatments are safe and effective. Therefore, it is imperative that participants in clinical trials represent the entire population who may use these treatments if they are approved. Despite this knowledge, participation in cancer clinical trials is low, and there is a serious lack of sociodemographic diversity among those who do participate. Recent data indicate that community outreach and patient navigation can enhance participation of racial and ethnic minority population groups in clinical trials. It is imperative that researchers and policymakers work together to address the many barriers to clinical trial participation.

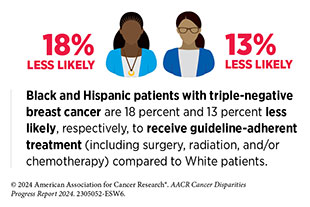

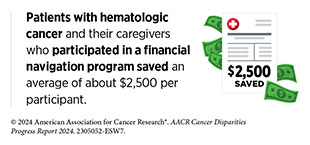

Remarkable advances in novel and innovative approaches to surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, molecularly targeted therapy, and immunotherapy—the five pillars of cancer treatment—are saving and improving lives. Despite these advances, racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations continue to experience more frequent and higher severity of multilevel barriers to quality cancer treatment, including treatment delays, lack of access to guideline-adherent treatment, undertreatment, refusal or early termination of treatment, treatment receipt at low-volume hospitals and community settings rather than comprehensive cancer centers, and higher rates of treatment-related and/or financial toxicities. Patients from disadvantaged population groups may also experience overt discrimination and/or implicit bias during the receipt of care.

Encouragingly, recent data show that racial and ethnic disparities in cancer outcomes can be eliminated if every patient has equitable access to guideline-adherent care. In fact, researchers have shown that certain patients with cancer from racial and ethnic minority populations may respond better to select treatments compared to White patients and have better outcomes when offered similar access to standard and quality care. All sectors must work together to urgently address the challenges of disparities in cancer treatment. In this regard, it should be noted that clinical studies, including the Accountability for Cancer through Undoing Racism and Equity (ACCURE) program, have shown that multilevel interventions that include addressing system-level barriers to care, connecting to resources, and providing psychosocial support through patient advocacy and navigation can address the current disparities in cancer treatment and improve outcomes for all patients.

Disparities in Cancer Survivorship

According to NCI, a person is considered a cancer survivor from the time of cancer diagnosis through the balance of the person’s life. With 18.1 million cancer survivors in the United States as of 2022, many more people are living through and beyond their cancer diagnosis. While these numbers are promising, medically underserved populations have higher rates of morbidity and mortality for many types of cancers. With the number of US individuals over the age of 65 and the diversity of the US population increasing, the number of cancer survivors who belong to racially and ethnically minoritized groups is projected to grow over the next few decades. Unless more equitable cancer control efforts are put in place, disparities across the cancer continuum, including survivorship, will widen, potentially increasing the future cancer burden.

Cancer treatments can be difficult for a patient’s physical and mental health and can contribute to potentially adverse side effects during or after cessation of treatment. Individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups and other medically underserved populations experience side effects at higher rates than those who are White. The adverse physical effects, coupled with worsened functional, psychological, social, and financial challenges, contribute to inferior health-related quality of life (HRQOL), an increasingly important consideration in cancer care, US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) drug approvals, and long-term survival predictions. It has long been recognized that HRQOL is lower in cancer survivors compared to individuals who have never been diagnosed with cancer. Furthermore, cancer survivors from medically underserved populations are at an increased risk of experiencing worse HRQOL.

Healthy behaviors, such as increasing physical activity, eating a healthy diet, reducing alcohol consumption, and not smoking, can significantly improve both health outcomes and HRQOL for cancer survivors. Unfortunately, many of the same barriers to participating in healthy behaviors discussed earlier in the context of cancer prevention also exist for cancer survivors. As one example, lack of access to exercise facilities and other types of recreational activity for racially and ethnically minoritized and medically underserved cancer survivors reduces participation in physical activity.

A key to charting an equitable path forward for cancer survivors who belong to disadvantaged populations is to implement community-based, culturally tailored solutions that include patient advocates and patient navigators as key partners to meet the specific needs of every patient. Such strategies can address the specific social, psychological, medical, and physical needs of the patient while tying in cultural norms and perceptions, and ultimately increasing HRQOL; bolstering adherence to follow-up survivorship care; identifying financial concerns; providing equitable health care; and reducing the overall cost of cancer care.

Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce

A diverse cancer research and patient care workforce includes individuals who represent a wide range of backgrounds, life experiences, and demographic groups, including differences in race, ethnicity, sexual orientation and gender identity, disability status, and socioeconomic background. A cancer care workforce that reflects the diversity of the US population enhances cultural competence and humility in delivering care to a diverse patient population, fosters innovation by integrating different perspectives and approaches, and elevates role models and mentors to inspire and support the next generation of historically underrepresented professionals in the cancer research and patient care workforce.

Some key strategies to increase diversity in the cancer research and care training pathway and workforce include ensuring early exposure to cancer research among students from underrepresented backgrounds; strengthening partnerships with minority-serving institutions; providing scholarships, grants, and loan repayment programs to help students from underrepresented groups overcome financial barriers to pursuing careers in cancer science and medicine; developing tailored recruitment programs to attract underrepresented minorities to cancer-related fields; implementing support systems and mentorship programs to retain the cancer workforce; and ensuring that leadership at cancer centers and research institutions is committed to diversity and health equity.

While there have been efforts to increase diversity in the cancer workforce, progress has been slow compared to the overall health care field. The underrepresentation of women, as well as racial and ethnic minority populations, in cancer science and medicine, remains a significant concern and may contribute to cancer disparities. In June 2023, the Supreme Court banned affirmative action in college admissions, striking down the use of race as an admissions factor. With affirmative action severely curtailed nationwide, substantial additional drops in historically underrepresented student admissions are expected, thus threatening diversity gains. Therefore it is vital that all constituents in the medical research and public health community work with policymakers to identify new and improved strategies that ensure continued progress toward a diverse and representative cancer care workforce.

Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Science-based Public Policy

Public policy is instrumental in addressing systemic barriers and promoting health equity to improve cancer outcomes for historically marginalized populations. Evidence-based policymaking can increase access to high-quality health care, enhance diverse representation in clinical studies, and remove barriers to facilitate access to cancer screening and preventive services.

Historically, the tobacco industry has aggressively targeted racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minority groups. Increased tobacco regulation is urgently needed to mitigate the disproportionately high disease burden from tobacco use among these populations.

Several government agencies, including NIH, FDA, and CDC, have developed policies and implemented programs to reduce disparities across the cancer care continuum. Sustained and meaningful collaboration across all branches of government is a promising strategy to reduce cancer disparities. Achieving long-term health equity in cancer outcomes will ultimately require intentional and multidimensional efforts from government, community organizations, health systems, researchers, nonprofit organizations, and all other stakeholders.

AACR Call to Action

Economic inequities, social injustices, and systemic barriers continue to adversely affect all facets of cancer research and patient care leading to a disproportionate burden of cancer for many US population groups. These disparities are driven by exposure to environmental carcinogens, limited access to health care and clinical trials, policies that exacerbate modifiable risk factors, such as smoking and lack of access to healthy food, and impediments to the development of a research and health care workforce that is broadly representative of our society.

Many programs and initiatives, both public and private, have been undertaken to address these challenges, but additional efforts and investments are urgently needed.

To make further progress toward eliminating cancer disparities, AACR calls on US policymakers to:

- Provide robust, sustained, and predictable funding increases for the US federal agencies and programs that are tasked with reducing cancer disparities.

- Support data collection initiatives to reduce cancer disparities.

- Increase access to and participation in clinical trials.

- Prioritize cancer control initiatives and increase screening for early detection and prevention.

- Implement policies to ensure equitable patient care.

- Reduce cancer disparities by building a more diverse and inclusive workforce.

- Enact comprehensive legislation to eliminate health inequities.

[A comprehensive list of recommendations is available in the AACR Call to Action.]

AACR has been a leader in advancing science to eliminate cancer disparities. The AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024 showcases the progress that has been made to address these disparities, while it highlights the many challenges that must be overcome. To fulfill the aims of the Call to Action and further advance health equity, partnerships will be required among diverse stakeholders, including federal, state, and local governments; the biopharmaceutical industry; academic and medical institutions; patient-centric and community-based organizations; and professional organizations. These collaborations must synergize with broader efforts in society to overcome economic inequities, dismantle structural barriers, and rectify social injustices to ensure the health and well-being of all patient populations.

Next Section: A Snapshot of US Cancer Disparities in 2024 Previous Section: A Message from AACR