- Eligibility for Cancer Screening

- Importance of Cancer Screening and Follow-up

- Disparities in Cancer Screening

- Breast Cancer Screening

- Cervical Cancer Screening

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

- Lung Cancer Screening

- Prostate Cancer Screening

- Eliminating Disparities in Cancer Screening Through Evidence-based Interventions

Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection

In this section, you will learn:

- Screening for cancer means looking for cancer or abnormal cells that may become cancerous in people who do not have any signs of the disease.

- Routine cancer screening and follow-up care saves lives.

- Racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations experience disparities in adherence to routine cancer screening and follow-up care.

- A multitude of systemic factors contribute to disparities in cancer screening.

- Research has identified a series of evidence-based interventions that are proving successful in reducing disparities in adherence to recommended cancer screening and follow-up care.

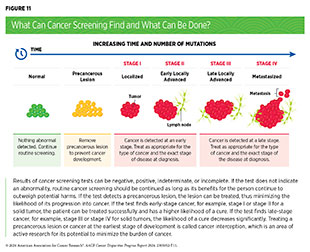

Cancer screening refers to checking for cancer, or abnormal cells that may become cancerous, in people who do not have signs or symptoms of the disease. The purpose of screening is to detect abnormalities at the earliest possible phase when cancer can be more effectively treated and is potentially curable (see Figure 11). Different kinds of tests are used for early detection, including laboratory tests that can detect cancer-related cellular or molecular changes in biospecimen samples, and imaging or endoscopic procedures that can look for cancer-specific abnormalities in the tissue (see Sidebar 20). Information obtained from cancer screening tests helps health care providers decide whether to monitor or treat precancerous lesions or early-stage cancer before they progress to a more advanced stage.

Eligibility for Cancer Screening

Guidelines for cancer screening are carefully developed by groups of subject matter experts convened by government agencies and some professional societies focused on public health. In this report, we use the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—a congressionally mandated independent panel of experts convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the US Health and Human Services (HHS) department—and its process for developing guidelines as an example. USPSTF’s mandate includes making evidence-based recommendations that can be used in primary care settings to prevent disease, including cancer.

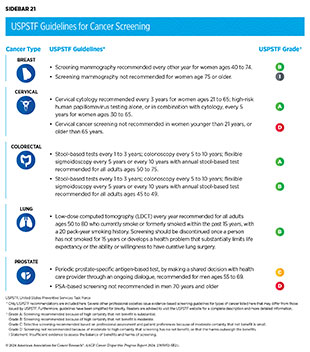

USPSTF guidance for cancer screening includes recommendations for screening certain individuals at certain intervals and recommendations against screening that has been shown to be harmful, as well as information that there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. For the finalized guidelines, USPSTF assigns a grade to its recommendations. The grade reflects confidence in the available evidence for the recommendation and also informs which services are covered without out-of-pocket costs under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). USPSTF can also assign different grades to different population groups within the same cancer type as part of its screening guidelines (see Sidebar 21). Throughout the process, USPSTF seeks input from the public. The finalized recommendations and review of the scientific evidence used to develop recommendations are published in a scientific journal and on the USPSTF website.

USPSTF develops cancer screening guidelines for individuals who are at an average risk of being diagnosed with cancer, as well as for those who are at a higher-than-average risk. Individuals at average risk of being diagnosed with cancer are those who do not have a family history of cancer or personal history of cancer, and do not have an inherited genetic condition that places them at a higher risk of developing cancer. Two key considerations for recommending screening in average-risk individuals are gender and age. Individuals at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer are those who have a strong family history of cancer, a personal history of cancer, certain tissue make-up, an inherited genetic condition, or who are exposed to one or more cancer risk factors, all of which place them at a higher risk of developing cancer. One example is individuals who smoke, which significantly increases their likelihood of developing lung cancer and dying from it (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors).

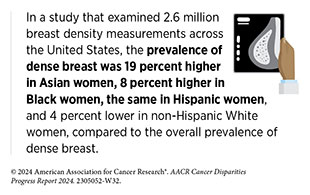

Another example of individuals at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer is women with extremely dense breast tissue. Density of the breast tissue in a mammogram is determined by the comparative amounts of fibrous, glandular, and fat tissues that make up the breast. The higher the amount of fibrous and glandular tissue, the denser the breast tissue appears in the mammogram. Having dense breast tissue is not considered abnormal, but it is one of the risk factors for developing breast cancer (495)Bodewes FTH, et al. (2022) Breast, 66: 62. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

People with inherited cancer susceptibility syndromes, also called hereditary cancer syndromes, constitute another group of individuals who are at higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer. Hereditary cancer syndromes are caused by genetic mutations that can be passed on from one generation to the next and can predispose an individual to develop certain types of cancer. For example, individuals who have Lynch syndrome, which is caused by mutations in genes important for repairing damaged DNA, have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer and several other types of cancer.

Some of the factors used to determine eligibility for cancer screening, such as exposure to cancer risk factors, are different for each person and may change throughout life. It is also noteworthy that cancer screening is a process and not a single test or scan. Depending upon the findings of the initial screening test, an individual may need follow-up exams and additional medical procedures. Therefore, it is important that people empower themselves with the most up-to-date information on cancer screening eligibility by having an ongoing dialogue with their health care providers and develop a personalized cancer screening plan that considers their specific risks and tolerance of potential harms from screening tests.

Importance of Cancer Screening and Follow-up

The overall goal of cancer screening is to reduce the burden of cancer in the general population. There are several benefits of adherence to the recommended cancer screening. Studies using real-world observations or computer models have shown that screening for cancer in eligible individuals prevents cancer deaths. Recent findings from a large, international study revealed that routine screening detected stage I lung cancer in 81 percent of 1,257 study participants who were diagnosed for the first time; 81 percent of those detected with, and treated for, stage I lung cancer were living 20 years after diagnosis (497)Henschke CI, et al. (2023) Radiology, 309: e231988. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent study using a mathematical model estimated that routine cancer screening has saved 12.2 to 16.2 million life-years, amounting to approximately $6.5 to $8.6 trillion in economic savings, since the introduction of USPSTF recommendations in 1996 (498)Philipson TJ, et al. (2023) BMC Health Serv Res, 23: 829. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another modeling study projected that just a 10-percentage point increase in adherence to the USPSTF-recommended cancer screening can prevent an estimated 15,580 additional deaths from lung, colorectum, breast, and cervix cancers combined (499)Knudsen AB, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2344698. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

While the benefits of routine cancer screening are many, cancer screening tests are medical procedures and do carry potential risks (see Sidebar 22). Researchers use several ways to assess and describe harms from cancer screening tests. One such method assesses the harms from cancer screening tests in four broad categories: physical effects, psychological effects, financial strain, and opportunity costs (500)Harris RP, et al. (2014) JAMA Intern Med, 174: 281. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Experts carefully consider risks and benefits of cancer screening tests when developing screening recommendations. Thus, findings of a recent study that some cancer screening recommendations and guidelines did not include potential harms associated with the tests are concerning (501)Kamineni A, et al. (2022) Ann Intern Med, 175: 1582. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is critical that the information about benefits and potential harms of cancer screening is clearly and easily available so that people can make an informed decision in consultation with their health care providers.

Disparities in Cancer Screening

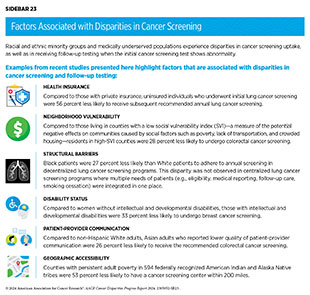

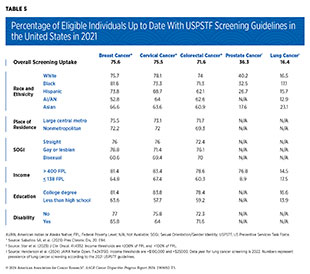

Following the recommended cancer screening is one of the most important ways to reduce cancer burden at the population level. Unfortunately, adherence to cancer screening remains suboptimal. Furthermore, screening patterns vary for different types of cancer among racial and ethnic minority groups, citizens of sovereign Native Nations, and medically underserved populations (see Table 5). Disparities in genetic testing for cancer risk are also prevalent (502)Mak J (2023) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 21: 430. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Multiple barriers contribute to low rates of cancer screening and genetic testing, including social and structural barriers; bias and discrimination against minoritized populations in the health care system; mistrust of health care professionals among minoritized populations; lack of access to quality health insurance and coverage; low health literacy; and miscommunication between patients and providers (see Sidebar 23). In this report, we discuss disparities in screening for five cancer types for which USPSTF currently has screening guidelines for individuals who are at an average risk of developing breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate cancers, as well as for individuals who are at a higher risk of developing lung cancer. We also highlight some of the interventions that have helped close disparities in cancer screening.

Breast Cancer Screening

Racial and ethnic minority populations and medically underserved communities experience substantial disparities in receiving the recommended breast cancer screening, as well as in the follow-up care if the screening mammogram shows an abnormality. In 2021 in the United States, only 52.8 percent American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) and 66.6 percent of Asian women were up to date with breast cancer screening, compared to 75.7 percent of non-Hispanic (NH) White women (see Table 5). Similar disparities in the receipt of breast cancer screening were apparent based on education, income, and sexual orientation (see Table 5). Furthermore, women under the age of 65 who had private insurance were about twice as likely to be up to date with breast cancer screening as those without any insurance (80.1 versus 42.3 percent, respectively) (509)Sabatino SA, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E94. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One study found that in 2019 in the United States, the rate of NH Asian women who were eligible for breast cancer screening but never received it was 12.6 percent, the highest among racial and ethnic minority populations (510)Lei F, et al. (2023) Cancer Control, 30: 10732748231202462. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Researchers are continually working to improve screening guidelines to capture cancers early, particularly in populations that may be at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. One study of nearly half a million women who died of breast cancer between 2011 and 2020—recommended start age for breast cancer screening was 50 years during this time—found that screening guidelines could be tailored specifically for women belonging to different racial and minority groups. For example, the findings suggested that screening for breast cancer could start 8 years earlier for Black women (511)Chen T, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e238893. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. USPSTF is currently finalizing recommendations to start breast cancer screening at age 40, which is expected to save 19 percent more lives from breast cancer (512)United States Preventive Services Taskforce. Draft Recommendation: Breast Cancer: Screening. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . Other professional societies are recommending that all Black women should undergo baseline assessment for future risk of breast cancer by a trained health care professional no later than age 25 years (513)Fayanju OM, et al. (2023) Ann Surg Oncol, 30: 58. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

A systematic review of the literature identified multiple barriers to adherence to breast cancer screening among vulnerable populations, including those with unemployment, lack of private health insurance, limited access to transportation, low income, and recency of immigration (515)Ponce-Chazarri L, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 604. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One study found that Asian women who recently immigrated to the United States had low rates of breast cancer screening compared to long-term immigrants or US-born Asian women (516)La Frinere-Sandoval Q, et al. (2023) Ethn Health, 28: 895. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another review found that compared to their heterosexual counterparts, lesbian and bisexual women were less likely to participate in mammography. Furthermore, transgender individuals had lower rates of screening than cisgender individuals for all cancer types (517)Heer E, et al. (2023) Prev Med, 170: 107478. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The study found that better communication with health care providers was the strongest facilitator among SGM individuals to stay up to date with routine cancer screening.

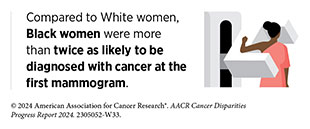

Research has also identified disparities across the cancer screening continuum. For example, findings from a recent study show that Black women had lower rates of referrals for breast cancer screening by a provider, compared to White women (9 percent vs. 13 percent, respectively), and 15 percent to 26 percent lower likelihood of completing mammography (518)Ganguly AP, et al. (2023) Cancer, 129: 3171. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study found that Black and Hispanic women living in rural Texas were, respectively, 33 percent and 22 percent less likely to be regular users of mammography compared to their urban counterparts (519)Liu Z, et al. (2024) Geriatr Nurs, 55: 14. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The study identified the lack of primary care physicians as one of the major barriers to routine breast cancer screening.

Cervical Cancer Screening

There are stark disparities in adherence to screening for cervical cancer. In 2021, only about 64 percent of eligible Asian and AI/ AN individuals were up to date with USPSTF-recommended cervical cancer screening compared to 78 percent of White individuals. Additionally, significant disparities existed based on income level, educational attainment, disability, and insurance status (see Table 5) (509)Sabatino SA, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E94. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Studies have also found that older eligible women (ages 60 to 64) were less likely to be up to date with cervical cancer screening (520)Sokale IO, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 82. .

Many other vulnerable populations also experience disparities in receipt of cervical cancer screening. For instance, members of the SGM community, especially those identifying as transgender, experience substantial disparities in routine screening for cervical cancer. According to a recent study, between 2016 and 2018, nearly 25 percent of transgender individuals reported that they have never been screened for cervical cancer in their lifetime, compared to 7 percent of cisgender individuals (521)Lin E, et al. (2024) Cancer Causes Control, 35: 133. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, 41.3 percent of Hispanic and 67.7 percent of API respondents who identified as transgender men indicated that they had never been screened for cervical cancer, compared to 20.5 percent of NH White respondents who identified as transgender men (521)Lin E, et al. (2024) Cancer Causes Control, 35: 133. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study found that women with two or more disabilities were 12 percent less likely to receive cervical cancer screening than women who did not have any disabilities (522)Orji AF, et al. (2024) Am J Prev Med, 66: 83. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Research has identified multiple factors, such as access to, and accommodation by, health care systems, that can help increase adherence to cervical cancer screening. For example, racial and ethnic minority patients and individuals with low household income often seek care at community health centers, as these facilities offer services to everyone, regardless of factors such as health insurance status (523)National Association of Community Health Centers. Community Health Center Chartbook 2020. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . One study investigated the association of ethnicity and preferred language with adherence to cancer screening at community health centers. Findings show that patients seen at clinics with higher concentrations of Spanish-preferring Hispanics were significantly more likely to be up to date with cervical cancer screening, as were individuals residing in areas with higher percentages of Spanish-speaking residents. Compared to NH White adults, Spanish-preferring Hispanic adults were 53 percent more likely and English-preferring Hispanic adults were 14 percent more likely to be up to date with cervical cancer screening. Furthermore, adherence to cervical cancer screening increased with an increase in the Spanish-speaking staff at the community health care facility (524)Springer R, et al. (2024) SSM Popul Health, 25: 101612. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It would be important to further examine how strategies that contribute to higher cervical cancer screening at community health centers can be implemented to other health care systems.

Another study found that having routine health care checkups was a strong predictor of being up to date with cervical cancer screening. The study compared a racially and ethnically diverse population of women who had a routine health care checkup within the past year with women who had a routine health care checkup more than 5 years ago or never had one (520)Sokale IO, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 82. . Findings revealed that women with a routine checkup within the year were significantly more likely to be up to date with cervical cancer screening, ranging from nearly nine times more likely for NH Asian women to 19 times more likely for NH Black women. Furthermore, women who received a mammogram for breast cancer screening were more than twice as likely to also be up to date with cervical cancer screening compared to women who did not receive a screening mammogram (520)Sokale IO, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 82. .

Immigration status also appears to play a significant role in adherence to the recommended cervical cancer screening. For example, immigrant NH Asian and Hispanic women were, respectively, 71 percent and 49 percent less likely to be up to date with cervical cancer screening compared to US-born NH White women. When adjusted for SES and access to care, the disparity was eliminated for immigrant Hispanic women, but not for immigrant Asian women (516)La Frinere-Sandoval Q, et al. (2023) Ethn Health, 28: 895. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Colorectal Cancer Screening

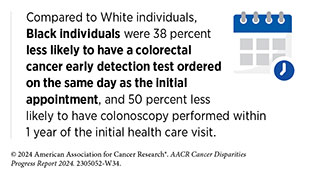

The percentage of adults up to date with colorectal cancer screening in 2021 was 72.2 percent (509)Sabatino SA, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E94. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, significant disparities existed among various population groups. Compared to NH White adults, uptake of colorectal cancer screening was substantially lower in Hispanic, Asian, and AI/AN adults. Furthermore, those living 138 percent below the federal poverty level, as well as those with less than a high school education, were less likely to be up to date with colorectal cancer screening (see Table 5). Similarly, compared to those with private insurance, uninsured individuals were 60 percent less likely to be up to date with colorectal cancer screening and 47 were percent less likely to receive a follow-up colonoscopy (509)Sabatino SA, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E94. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](525)Khoong EC, et al. (2023) J Gen Intern Med, 38: 21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Another study, evaluating data from more than 220,000 adults, reported that individuals from all racial and ethnic minority populations had significantly lower likelihood of being up to date with colorectal cancer screening, compared to NH White individuals. Importantly, accounting for certain SDOH, such as income and education; behavioral factors, such as smoking status, i.e., those who are currently smoking; and other demographics, such as age and sex; either eliminated or significantly reduced this disparity (526)Kane WJ, et al. (2023) Dis Colon Rectum, 66: 1223. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For example, after accounting for these factors, the disparity in the receipt of colorectal cancer screening decreased by 21 percentage points for Black adults, 25 percentage points for Hispanic adults, and 20 percentage points for AI/AN adults, although it remained lower compared to NH White adults (526)Kane WJ, et al. (2023) Dis Colon Rectum, 66: 1223. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These findings indicate that addressing SDOH can help decrease disparities in adherence to colorectal cancer screening and follow-up care.

In 2021, USPSTF revised its recommendation to start colorectal cancer screening at the age of 45 (189)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2021. Accessed: June 30, 2023. . However, researchers have raised concerns that the implementation of revised recommendations can further increase colorectal cancer disparities, especially for Black and AI/AN populations. As one example, an estimated 10.7 million additional colonoscopies may be required as a result of the recommendation change, which can limit access among medically underserved populations unless the number of facilities with a capacity to perform colonoscopies are expanded (528)Mehta SJ, et al. (2021) JAMA Netw Open, 4: e2112593. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Immigration status and length of stay in the United States is also an important determinant of adherence to colorectal cancer screening. One study found that individuals who immigrated to the United States within the past 15 years were 21 percent less likely to be up to date with colorectal cancer screening compared to those who were born in the United States (529)Santiago-Rodriguez EJ, et al. (2023) Am J Prev Med, 65: 74. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The analysis showed additional variations among different racial and ethnic populations. Asian and Hispanic individuals who immigrated to the United States within the past 15 years were, respectively, 26 percent and 14 percent less likely to be up to date with colorectal cancer screening compared to those who were born in the United States (529)Santiago-Rodriguez EJ, et al. (2023) Am J Prev Med, 65: 74. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Benefits of colorectal cancer screening are highlighted by a recent modeling study (530)Rutter CM, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 2023: 196. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers used incidence rates of colorectal cancer among White and Black people from 1979 to 2018 to estimate the effect of colorectal screening on lifetime incidence rates. The model projected that routine colorectal cancer screening would decrease lifetime incidence rates for colorectal cancer and increase total life-years saved in both populations, but the benefit was greater for Black people (530)Rutter CM, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 2023: 196. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Lung Cancer Screening

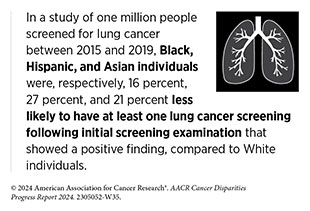

Despite the evidence that adhering to screening reduces lung cancer-related deaths by more than 20 percent (531)Aberle DR, et al. (2011) N Engl J Med, 365: 395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](532)de Koning HJ, et al. (2020) N Engl J Med, 382: 503. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], only 5.8 percent of eligible individuals in the United States were up to date with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in 2021 (311)Carter-Harris L (2015) J Am Assoc Nurse Pract, 27: 240. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, a recent study found that adherence to the recommended follow-up annual lung cancer screening after a positive LDCT finding was only 22.3 percent among more than one million patients who underwent initial screening between 2015 and 2019 (503)Silvestri GA, et al. (2023) Chest, 164: 241. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition to the overall low adherence rates for LDCT, significant disparities exist between White individuals and those belonging to racial and ethnic minority populations (see Table 5).

A systematic review and meta-analysis of nine studies found that Black individuals were 33 percent less likely than White individuals to adhere to follow-up recommendations after the initial LDCT. Furthermore, compared to White individuals, Black individuals were 44 percent less likely to follow up after a positive LDCT finding (533)Kunitomo Y, et al. (2022) Chest, 161: 266. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These findings are concerning because Black people are more likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer at an advanced stage (2)Islami F, et al. (2023) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 136 [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], highlighting the critical need for adhering to routine screening and follow-up.

Researchers are continually improving eligibility criteria for lung cancer screening. In March 2021, USPSTF revised its recommendation for lung cancer screening, which significantly increased the number of eligible people who are considered at high risk for lung cancer, including women and Black individuals. Initial evaluation suggested that revised guidelines have reduced eligibility disparities, especially for Black adults (534)Ritzwoller DP, et al. (2021) JAMA Netw Open, 4: e2128176. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](535)Pu CY, et al. (2022) JAMA Oncol, 8: 374. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, recent studies have shown that the guidelines still fall short of accounting for all the racial and ethnic differences in lung cancer risk. For example, two recent studies compared the updated 2021 USPSTF guidelines, which are based on age and smoking history, with a risk-based criteria that accounted for additional factors, including family history and other health issues, such as previous cancer diagnoses (536)Aredo JV, et al. (2022) JNCI Cancer Spectr, 6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](537)Choi E, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 1640. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One study of nearly 6,000 lung cancer cases from a diverse patient population found that, compared to 2021 USPSTF guidelines, using the guidelines founded on a risk-based model has the potential to reduce the lung cancer screening disparity by more than half for Black adults, but increased it by more than double for Hispanic individuals compared to White adults (536)Aredo JV, et al. (2022) JNCI Cancer Spectr, 6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The second study used data from more than 100,000 adults from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds with a history of smoking. Similar to the first study their findings also show that the risk-based guidelines have a greater potential to reduce lung cancer screening disparities between Black and White populations (537)Choi E, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 1640. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Disparities in adherence to lung cancer screening also exist in other racial and ethnic populations. As one example, a recent study from Hawai‘i showed that there was a 14 percent to 15 percent gap in completion of lung cancer screening among various population groups (538)Oshiro CES, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2144381. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Findings from the study show that Asian individuals had the highest screening completion rate (86 percent), followed by Native Hawaiian (80 percent) and NH White individuals (80 percent), and Pacific Islander individuals (79 percent). Within Asian subpopulations, Korean (94 percent) and Japanese (88 percent) individuals had the highest completion rates followed by Chinese individuals (82) and Filipino individuals (79 percent) (538)Oshiro CES, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2144381. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Evidence indicates that racial disparities in lung cancer screening are attributable to multilevel factors that include socioeconomic factors, such as cost, as well as structural barriers, such as transportation. However, a recent study found that disparities in the completion of lung cancer screening between White and Black patients persisted at a Veterans Affairs health care system, where health care system–related barriers are minimal. Of the 4,562 veterans who were referred for lung cancer screening, only 37 percent completed screening overall, and Black veterans were 34 percent less likely to complete screening compared to White veterans (539)Navuluri N, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2318795. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study of individuals with a history of smoking found that the receipt of annual lung cancer screening was significantly less among Black patients compared to White patients (23.6 percent vs. 33.6 percent, respectively) (540)Kim RY, et al. (2023) Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 207: 777. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The study also showed that as the neighborhood SES where patients lived improved, adherence to lung cancer screening for both White and Black patients also increased, eliminating half of the racial disparity. These findings further indicate that racial disparities in lung cancer screening are not fully explained by SES differences.

Prostate Cancer Screening

According to the most recent estimates, in 2021, 40.2 percent of White men, 32.5 percent of Black men, and 26.7 percent of Hispanic men ages 55 to 69 years had a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test to screen for prostate cancer within the past year (see Table 5) (541)National Cancer Institute. Cancer Treads Progress Reports. Prostate Cancer Screening. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Recent evidence from the US Veterans Health Administration comparing PSA screening tests and prostate cancer diagnoses between 2005 and 2019 across 128 facilities suggests that facilities with higher PSA screening rates had lower rates of metastatic prostate cancer 5 years later (542)Bryant AK, et al. (2022) JAMA Oncol, 8: 1747. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Current USPSTF guidelines for individuals at an average risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer recommend shared decision-making in which individuals should routinely discuss benefits and potential harms of receiving PSA testing with their health care provider (see Sidebar 21). The guidance for a shared decision is because data are lacking to make a specific recommendation. As one example, even though Black men have an estimated 70 to 110 percent higher incidence and mortality rate for prostate cancer than White men (543)Schafer EJ, et al. (2023) Eur Urol, 84: 117. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], they were poorly represented in the screening studies that informed current guidelines (544)Oren O, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: e18057. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers are suggesting that a discussion about prostate cancer screening between Black individuals and their health care provider should start at a younger age (e.g., 45 to 50 years) and at more frequent intervals compared to other racial and ethnic groups (545)Kensler KH, et al. (2024) J Natl Cancer Inst, 116: 34. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Although large-scale data remain sparse, there is accumulating evidence of significant disparities in prostate cancer screening for transgender individuals. Researchers have found that prostate cancer screening rates are significantly lower among eligible transgender women (546)Premo H, et al. (2023) Urology, 176: 237. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One study found that transgender women were 35 percent less likely to have received prostate cancer screening compared to cisgender men (547)Kalavacherla S, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2356088. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Importantly, when providers recommended the PSA test and initiated a discussion of its advantages and disadvantages, the disparity was nearly eliminated, and transgender women were 12 times more likely to have recently undergone screening (547)Kalavacherla S, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2356088. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Research has shown that shared decision-making between a patient and a provider is critical to increasing uptake in prostate cancer screening. One study found that, compared to men who received no information about PSA testing from their health care provider, men who received information about both benefits and harms were three times more likely to undergo PSA testing (548)McCormick ME, et al. (2023) J Cancer Educ, 38: 1313. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similarly, another study of nearly seven million men who received PSA screening for prostate cancer in 2020 showed that shared decision-making more than doubled the likelihood of PSA screening (549)Frego N, et al. (2024) Am J Prev Med, 66: 27. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, Black and Hispanic men were less likely to report shared decision-making and were, respectively, 23 percent and 49 percent less likely to undergo PSA screening compared to White men (549)Frego N, et al. (2024) Am J Prev Med, 66: 27. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Eliminating Disparities in Cancer Screening Through Evidence-based Interventions

Disparate adherence to cancer screening and follow-up care contributes to disproportionately higher rates of advanced-stage cancer diagnoses and cancer-related deaths in racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations. However, eliminating disparities in cancer screening requires that the root causes of suboptimal uptake in screening and follow-up care are identified and addressed. All sectors must work in concert to develop and implement multipronged approaches to dismantle structural racism, discrimination, and other societal inequities that pose significant barriers in equitable access to all aspects of the cancer screening continuum. In the following sections, we highlight some of the evidence-based interventions that have proven to be effective in increasing cancer screening awareness, adherence, and follow-up in racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations. It is also important to note that not all evidence-based interventions are effective for all communities, and additional work is required to refine these approaches for specific populations.

Public Health Campaigns

In 2015, CDC funded the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) with the goal of increasing CRC screening. The program provided funds to states, organizations, and institutes to develop partnerships with primary care clinics and implement four evidence-based interventions: patient reminders, provider reminders, reduction of structural barriers, and provider assessment and feedback. In its current iteration, initiated in 2020, CRCCP has funded 35 awardees that include state public health departments, universities and institutes, and tribal organizations (551)Subramanian S, et al. (2022) Implement Sci Commun, 3: 110. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Since its launch, awardees of the CRCCP program have taken several approaches to increase CRC screening among populations they serve. For example, the Iowa Get Screened: Colorectal Cancer Program, which helps people with low income get screened for CRC, offered patients payment for gas if they had to travel to the clinic to drop off their fecal immunochemical test kit. The intervention increased CRC screening from about 33 percent in 2015 to 57 percent in 2020 (552)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal Cancer Control Program. Award Recipient Highlights. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

As part of the intervention, a health center in Chicago trained medical assistants about CRC and how to educate patients about it; they sent reminder text messages to patients to get screened, and, on provider reports, included information about the number of patients who should have been offered a screening. As a result of this multipronged approach, the overall CRC screening nearly doubled in 4 years. During the same time, the number of tests ordered for Hispanic patients increased nearly three times (from 17 percent to 49 percent), while the returned completed test increased more than 10 times (from 3.5 percent to almost 37 percent) (552)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal Cancer Control Program. Award Recipient Highlights. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

CDC also administers the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), which provides those with low income and without adequate insurance access to breast and cervical cancer screening, among other services (e.g., patient navigation) to overcome structural barriers and get quality care (see Funding Research and Supporting Innovative Programs to Address Disparities and Promote Health Equity). Currently in its 33rd year, the program provided more than 300,000 breast and cervical cancer screenings in 2022 alone, the most recent year for which such data are available (152)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Access to Health Insurance

Access to, and quality of, health care insurance is a significant contributor to disparities in uptake of cancer screening. In a recent study, researchers used data from National Health Interview Surveys (2010, 2015, 2018, 2019, and 2021) to address the role of access to health insurance in adherence to cancer screening. The findings show that patients without health insurance coverage had the lowest screening rates (553)Shi KS, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: 116. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, patients who had continuous private health insurance coverage had higher screening rates for breast cancer (80.5 percent), colorectal cancer (65.4 percent), and cervical cancer (80 percent). In contrast, patients who had gaps in health insurance coverage had lower screening rates (63.1 percent for breast cancer, 47.1 percent for colorectal cancer, and 73.1 percent for cervical cancer) (553)Shi KS, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: 116. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The ACA and the associated expansion in Medicaid eligibility adopted by most states has positively impacted access of medically underserved populations to health care (see Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Screening and Follow-up Care) (554)Ercia A (2021) BMC Health Serv Res, 21: 920. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One study found a 16 percent increase in colorectal cancer screening among low-income individuals living in states with expanded Medicaid eligibility compared to those living in states with no Medicaid expansion (555)Qian Z, et al. (2023) Dig Dis Sci, 68: 1780. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Culturally Tailored Strategies

Researchers are also taking innovative approaches by engaging communities to increase awareness about the importance of undergoing routine cancer screening, participating in clinical trials, and reducing exposure to modifiable cancer risk factors. For example, researchers developed a culturally tailored approach—using bilingual community health workers to give presentations, develop educational materials, and follow up with participants—to promote the use of HPV self-sampling tests among low-income Asian women with low English proficiency. Among the 156 participants, HPV knowledge doubled and the comfort of participants with the HPV self-sample test increased significantly (556)Ma GX, et al. (2022) Cancer Control, 2022: 29. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

A systematic review of studies evaluating interventions to increase cancer screening rates found that video interventions were particularly effective in increasing cervical and breast cancer screening, especially in low-income Black women. Furthermore, videos that included culturally tailored educational material were generally more effective than information-only videos (558)Richardson-Parry A, et al. (2023) J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 0: 00. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study combined culturally adapted education material with patient navigation to increase breast and cervical cancer screening among Muslim women in New York City. Between the start of the intervention and the 4-month follow-up, mammography increased from 16 percent to 49 percent, and cervical cancer screening increased from 17 percent to 42 percent (559)Wyatt LC, et al. (2023) J Cancer Educ, 38: 682. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Colorectal cancer adversely affects Indigenous populations (see Table 1), further highlighting the needs for effective and culturally tailored interventions to raise the awareness and utilization of colorectal cancer screening in these communities. In a recent study, Indigenous and rural community outreach teams partnered with a community advisory board to provide an indigenized/ruralized version of the NCI Screen to Save program to both Indigenous and rural/suburban communities (560)Maybee W, et al. (2024) J Cancer Educ, 39: 65. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Findings show that Indigenous/rural participants who received the culturally tailored educational material successfully identified smoking and tobacco use, as well as physical inactivity, as risk factors for colorectal cancer. Importantly, participants reported that their cancer screening experiences have increased their likelihood, as well as the likelihood of their family and friends, to receive subsequent routine screening for colorectal cancer. This example further underscores that culturally tailored interventions are effective for increasing screening awareness and adherence among Indigenous and rural populations (560)Maybee W, et al. (2024) J Cancer Educ, 39: 65. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Community Engagement and Patient Navigation

One of the key reasons that many people are not up to date with the recommended cancer screening is structural barriers, such as the lack of transportation and language barriers, among others. In an effort to improve adherence to cancer screening, constituents across the cancer care continuum are implementing a variety of interventions to reduce these barriers. For example, one cancer center in Florida implemented a multilevel strategy to improve uptake of lung cancer screening. The center alerted eligible patients about screening through electronic notifications, provided culturally competent patient navigators, arranged for interpreters to address language barriers, and held teaching sessions for providers about lung cancer and motivational communication skills (561)Gay NA, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 6518. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. During the 1-year pilot program (January 2022 through December 2022), the overall lung cancer screening increased from 20 percent to 25 percent, and screening rates were higher among Hispanic and Black patients (12 and 8 percent, respectively), compared to NH White patients (6 percent) (561)Gay NA, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 6518. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

In another study, researchers implemented an innovative multidisciplinary strategy to improve access to cancer screening for the predominantly Black, medically underserved residents in West Philadelphia (562)Ginzberg SP, et al. (2023) Acad Radiol, 30: 3153. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A “one-stop-shop” health fair, held in the heart of the community, included eight core stations that provided various services from screening exams to financial counseling. The health fair was attended by 350 participants, and a total of 232 screening tests or assessments were completed. An additional 153 women underwent screening mammography during the subsequent 3 weeks at the mobile mammography unit (562)Ginzberg SP, et al. (2023) Acad Radiol, 30: 3153. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Cancer screening rates are lower in populations with limited English proficiency, who experience additional barriers to care. Many of these populations are served by community health care centers, where uptake of cancer screening is low. For example, uptake of colorectal cancer screening at community health care centers is 43 percent compared to the national average of 80 percent (564)Glaser KM, et al. (2024) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. To overcome these barriers, one urban community health care center implemented patient navigation and culturally tailored education at one of its two sites; the other site was used as a reference point to examine the impact of the interventions. Findings show that patient navigation helped increase colorectal cancer screening from 31 percent to 59 percent between August 2016 and December 2018, with the most notable increase in patients with low English proficiency (564)Glaser KM, et al. (2024) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. At the end of the pilot program in December 2018, compared to English-speaking patients, non– English-speaking patients were, respectively, two times and three times more likely to receive colorectal cancer screening by colonoscopy or a stool-based test (564)Glaser KM, et al. (2024) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Improved Patient-Provider Communications

Research has shown that clear communication between patients and providers improves delivery of quality health care. One study evaluated the effectiveness of different communication methods after the initial LDCT for lung cancer screening showed a positive finding (565)Henderson LM, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2320409. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers found that patients whose communications mentioned “benign” findings were 46 percent less likely to receive recommended follow-up care compared to those whose communications did not mention “benign.” In contrast, patients whose communications mentioned “abnormal” or “suspicious” findings were 51 percent more likely to receive a follow-up exam. The study also found that patients who spoke to their health care providers about the initial findings by phone were three times more likely to receive follow-up care than those whose results were communicated by letter, voicemail, text, e-mail, or online portal (565)Henderson LM, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2320409. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Next Section: Disparities in Clinical Research and Cancer Treatment Previous Section: Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors