Disparities in Cancer Survivorship

In this section, you will learn:

- Cancer survivorship encompasses the physical and mental health-related issues, as well as the social and financial challenges, encountered by anyone who has received a cancer diagnosis.

- Those belonging to racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations experience higher rates of adverse side effects, poorer quality of life, and higher financial toxicity resulting from a cancer diagnosis.

- Pediatric, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors who belong to medically underserved populations experience increased financial toxicity, adverse side effects, and differences in the types of palliative care services they receive.

- To improve the survivorship experience for racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations, patient navigators, patient advocates, and culturally sensitive intervention/navigation programs need to be used.

A cancer survivor is anyone who has been diagnosed with any cancer. Cancer survivorship includes the time from initial diagnosis (often called the acute phase) until end of life (also called the chronic phase). With nearly 17 million cancer survivors in the United States as of 2019, many more people are living through and beyond their cancer. While these numbers are promising, medically underserved populations have higher rates of incidence and mortality for many types of cancers (17)Miller KD, Ortiz AP, Pinheiro PS, Bandi P, Minihan A, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer Statistics for the US Hispanic/Latino Population, 2021. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2021;71:466-87. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](642)Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer Statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. With the projected increase in cancer survivors who belong to racial and ethnic minorities, disparities across the cancer continuum will potentially widen, because both the numbers of U.S. individuals over the age of 65 and the diversity of the U.S. population are increasing (643)Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of Cancer Incidence in the United States: Burdens Upon an Aging, Changing Nation. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2758-65. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](644)Lee Smith J, Hall IJ. Advancing Health Equity in Cancer Survivorship: Opportunities for Public Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2015;49:S477-S82. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](645)Nguyen J, Napalkov P, Richie N, Arndorfer S, Zivkovic M, Surinach A. Impact of US Population Demographic Changes on Projected Incident Cancer Cases from 2019 to 2045 in Three Major Cancer Types. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:e19044. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](646)The Chance That Two People Chosen at Random Are of Different Race or Ethnicity Groups Has Increased since 2010. [updated April 22, 2022, cited.

As more people are living longer and fuller lives after a cancer diagnosis, thanks to improved diagnosis and treatment options, greater attention is needed to understand the survivorship experience. These experiences include the physical, psychosocial, and economic adversities caused by a cancer diagnosis, such as the need for long-term follow-up care and the increased risk of secondary cancers, among others. While all survivors of cancer have unique experiences, it is becoming clear that those belonging to medically underserved populations shoulder a disproportionate burden of the adverse effects of cancer survivorship. Outlining the challenges faced by these groups will help inform cancer care strategies and personalized recommendations for those who are more vulnerable, leading to better quality of life.

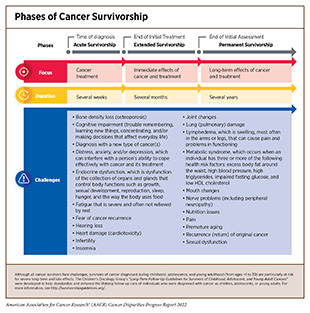

Long-Term and Late Effects of Cancer Treatment

Cancer treatments can impact a patient’s physical and mental health. When a cancer survivor experiences adverse side effects that begin during treatment and continue afterward, these are called long-term side effects; nearly one-third of cancer survivors experience long-term side effects (647)Wu H-S, Harden JK. Symptom Burden and Quality of Life in Survivorship: A Review of the Literature. Cancer Nursing 2015;38(1):E29-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Late-term side effects happen after the conclusion of treatment and can occur for the lifetime of the survivor. Side effects are unique to each individual and are dependent on multiple factors such as cancer type, treatment, physical health, and mental well-being. Recent studies are highlighting the disparities in both long- and late-term effects of cancer treatments in medically underserved populations. As evident from such studies, these groups experience lower rates of fertility preservation (648)Meernik C, Engel SM, Wardell A, Baggett CD, Gupta P, Rodriguez-Ormaza N, et al. Disparities in Fertility Preservation Use among Adolescent and Young Adult Women with Cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], neurological challenges such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (433)Mazor M, Wisnivesky JP, Goel M, Harris YT, Lin JJ. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Post-Traumatic Stress and Illness Coherence in Breast Cancer Survivors with Comorbid Diabetes. Psycho-Oncology 2021;30:1789-98. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](469)White PM, Itzkowitz SH. Barriers Driving Racial Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening in African Americans. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2020;22:41. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], lymphedema (650)Chang DW, Suami H, Skoracki R. A Prospective Analysis of 100 Consecutive Lymphovenous Bypass Cases for Treatment of Extremity Lymphedema. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2013;133(6):887e-888e. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], metabolic disorders (651)Yoshida Y, Schmaltz CL, Jackson-Thompson J, Simoes EJ. The Effect of Metabolic Risk Factors on Cancer Mortality among Blacks and Whites. Translational Cancer Research 2019:S389-S96. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], diabetes (652)Yao Yuan MT, and Avonne E. Connor. The Effects of Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health on the Relationship between Race and Health Status in U.S. Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Women’s Health 2019;28:1632-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], heart failure (653)Noyd DH, Yasui Y, Li N, Chow EJ, Bhatia S, Landstrom A, et al. Disparities in Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Race/Ethnicity among Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivorship Study (CCSS). J Clin Oncol 2021;39:10017. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], cardiac dysfunction (654)Yuan Y, Taneja M, Connor AE. The Effects of Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health on the Relationship between Race and Health Status in U.S. Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Women’s Health 2018;28:1632-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](655)Williams MS, Beech BM, Griffith DM, Jr. Thorpe RJ. The Association between Hypertension and Race/Ethnicity among Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2020;7:1172-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], recurrence of cancer (656)Manz CR, Schrag D. Racial Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Recurrence and Mortality: Equitable Care, Inequitable Outcomes? JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2021;113:656-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](657)Kabat GC, Ginsberg M, Sparano JA, Rohan TE. Risk of Recurrence and Mortality in a Multi-Ethnic Breast Cancer Population. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2017;4:1181-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and development of new, secondary cancers (659)Lindström L. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Rates of Invasive Secondary Breast Cancer among Women with Ductal Carcinoma in Situ in Hawai‘i. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2130925. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](660)Scott LC, Yang Q, Dowling NF, Richardson LC. Predicted Heart Age among Cancer Survivors – United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (see sidebar on Phases of Cancer Survivorship).

Many common cancer treatments damage the cardiovascular system, further exacerbating complications in cancer survivors. Research has shown that cancer survivors have an “excess heart age”—a measure of cardiovascular damage and risk for a heart attack—of eight and a half years in men and six and half years in women compared to those individuals who have never received a cancer diagnosis (660)Scott LC, Yang Q, Dowling NF, Richardson LC. Predicted Heart Age among Cancer Survivors – United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Average excess heart age was shown to be higher in cancer patients who are NHB, less educated, and have lower income. Other cardiovascular conditions like thrombosis, which is a result of blood clots in veins and arteries, are more common in patients who are Black, regardless of cancer type (except myeloma) and can lead to pain and swelling as well as stroke and heart attack (661)Datta T, Brunson A, Mahajan A, Keegan TH, Wun T. Racial Disparities in Cancer-Associated Thrombosis. Blood Adv 2022;6:3167–3177. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, several studies have shown disproportionately higher rates of cardiovascular disease in Black cancer patients (655)Williams MS, Beech BM, Griffith DM, Jr. Thorpe RJ. The Association between Hypertension and Race/Ethnicity among Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2020;7:1172-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](662)Ohman RE, Yang EH, Abel ML. Inequity in Cardio-Oncology: Identifying Disparities in Cardiotoxicity and Links to Cardiac and Cancer Outcomes. Journal of the American Heart Association 2021;10:e023852. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](663)Collin LJ, Troeschel AN, Liu Y, Gogineni K, Borger K, Ward KC, et al. A Balancing Act: Racial Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease Mortality among Women Diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Annals of Cancer Epidemiology 2020;4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](664)Stoltzfus KC, Zhang Y, Sturgeon K, Sinoway LI, Trifiletti DM, Chinchilli VM, et al. Fatal Heart Disease among Cancer Patients. Nature communications 2020;11:2011. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], with one study of over 400,000 patients with breast cancer showing mortality related to cardiovascular disease occurring in 13.3 percent of NHB patients compared to only 8.9 percent of NHW patients (665)Troeschel AN, Liu Y, Collin LJ, Bradshaw PT, Ward KC, Gogineni K, et al. Race Differences in Cardiovascular Disease and Breast Cancer Mortality among US Women Diagnosed with Invasive Breast Cancer. International Journal of Epidemiology 2019;48:1897-905. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Further concerning are data indicating that NHB breast cancer survivors were 15 percent more likely not to adhere to cardiovascular medication schedules after treatment, increasing the likelihood of having a cardiac event (666)Hershman DL, Accordino MK, Shen S, Buono D, Crew KD, Kalinsky K, et al. Association between Nonadherence to Cardiovascular Risk Factor Medications after Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Incidence of Cardiac Events. Cancer 2020;126:1541-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

One challenge faced by cancer survivors is infertility or the inability to conceive a child that can be a consequence of cancer treatments. This can occur in both men and women as a result of surgery on reproductive organs or effects of cancer medications on reproductive cells. In anticipation of impaired reproductive abilities, patients may choose to store reproductive material in a process called fertility preservation prior to cancer treatment. Rates of fertility preservation among patients with cancer is an area of active investigation, but emerging data show that rates vary among men and women, cancer type, treating institution, and age (667)Lambertini M, Del Mastro L, Pescio MC, Andersen CY, Azim HA, Jr., Peccatori FA, et al. Cancer and Fertility Preservation: International Recommendations from an Expert Meeting. BMC Med 2016;14:1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](668)Pinelli S, Basile S. Fertility Preservation: Current and Future Perspectives for Oncologic Patients at Risk for Iatrogenic Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. BioMed Research International 2018;2018:6465903. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](669)Patel P, Kohn TP, Cohen J, Shiff B, Kohn J, Ramasamy R. Evaluation of Reported Fertility Preservation Counseling before Chemotherapy Using the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative Survey. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2010806. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Trends show, however, that women cancer survivors who were Black, poor, or lived in rural areas, had decreased rates of fertility preservation (648)Meernik C, Engel SM, Wardell A, Baggett CD, Gupta P, Rodriguez-Ormaza N, et al. Disparities in Fertility Preservation Use among Adolescent and Young Adult Women with Cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](670)Voigt P, Persily J, Blakemore JK, Licciardi F, Thakker S, Najari B. Sociodemographic Differences in Utilization of Fertility Services among Reproductive Age Women Diagnosed with Cancer in the USA. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022;39:963-972. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Currently, cancer-focused organizations have guidelines that discuss fertility preservation and sexual health as an essential part of cancer management, especially in AYA populations (671)Coccia PF, Pappo AS, Beaupin L, Borges VF, Borinstein SC, Chugh R, et al. Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, Version 2.2018, Nccn Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018;16:66-97. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, as of February 2022, 10 states have mandates, and 12 more have active legislation, requiring insurance coverage of fertility preservation for patients facing infertility due to treatments such as anticancer therapies (672)Alliance for Fertility Preservation. State Laws & Legislation. [updated March 28, 2022, cited 2022 April 22]..

Lymphedema is a common long-term side effect among survivors of colorectal, endometrial, and breast cancer that results from damage to the lymphatic system after cancer surgery (673)Zhang X, McLaughlin EM, Krok-Schoen JL, Naughton M, Bernardo BM, Cheville A, et al. Association of Lower Extremity Lymphedema with Physical Functioning and Activities of Daily Living among Older Survivors of Colorectal, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e221671. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This damage disrupts normal draining of lymphatic fluid, instead leading to accumulation in the surrounding tissue, resulting in painful swelling most commonly in the arms and legs (673)Zhang X, McLaughlin EM, Krok-Schoen JL, Naughton M, Bernardo BM, Cheville A, et al. Association of Lower Extremity Lymphedema with Physical Functioning and Activities of Daily Living among Older Survivors of Colorectal, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e221671. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](674)Hayes SC, Janda M, Cornish B, Battistutta D, Newman B. Lymphedema after Breast Cancer: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Effect on Upper Body Function. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3536-42. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](675)Armer JM, Ballman KV, McCall L, Ostby PL, Zagar E, Kuerer HM, et al. Factors Associated with Lymphedema in Women with Node-Positive Breast Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Axillary Dissection. JAMA Surgery 2019;154:800-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Black women are 3.85 times and Hispanic women 1.47 times more likely to develop breast cancer-related lymphedemas compared with White women (676)Kwan ML, Yao S, Lee VS, Roh JM, Zhu Q, Ergas IJ, et al. Race/Ethnicity, Genetic Ancestry, and Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema in the Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2016;159:119-29. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](677)Barrio AV, Montagna G, Sevilimedu V, Gomez EA, Mehrara B, Morrow M. Abstract Gs4-01: Impact of Race and Ethnicity on Incidence and Severity of Breast Cancer Related Lymphedema after Axillary Lymph Node Dissection: Results of a Prospective Screening Study. Cancer Research 2022;82:GS4-01. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Limited access to medical resources including surgery, physical therapy, and medical equipment, coupled with barriers to maintaining a healthy diet and exercise to reduce swelling, increase lymphedema occurrence and severity and reduce quality of life (326)Rock CL, Thomson CA, Sullivan KR, Howe CL, Kushi LH, Caan BJ, et al. American Cancer Society Nutrition and Physical Activity Guideline for Cancer Survivors. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians;72:230-262. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Implementation of behavioral strategies that reduce the risk of developing adverse health conditions by promoting risk reduction strategies (e.g., smoking cessation and maintaining a healthy weight) in patients with cancer are important for reducing side effects of cancer treatment. Lifestyle programs to reduce obesity such as the obesity-related behavioral intervention trials (ORBIT) can help combat these risks and are being evaluated in specific vulnerable populations (678)Porter KJ, Moon KE, LeBaron VT, Zoellner JM. A Novel Behavioral Intervention for Rural Appalachian Cancer Survivors (Wesurvive): Participatory Development and Proof-of-Concept Testing. JMIR Cancer 2021;7:e26010. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, activities such as walking have been shown to reduce obesity and improve health outcomes in cancer survivors (679)Robinson JRM, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Schwartz AG, Ruterbusch JJ, Baird TE, Pandolfi SS, et al. Neighborhood Walkability and Body Mass Index in African American Cancer Survivors: The Detroit Research on Cancer Survivors Study. Cancer 2021;127:4687-93. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For example, one study has shown that exercise benefited the physical well-being of Black breast cancer survivors to a greater degree than White breast cancer survivors (680)Owusu C, Margevicius S, Nock NL, Austin K, Bennet E, Cerne S, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effect of Supervised Exercise on Functional Outcomes in Older African American and Non-Hispanic White Breast Cancer Survivors: Are There Racial Differences in the Effects of Exercise on Functional Outcomes? Cancer 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, neighborhood walkability, (i.e. how much a neighborhood supports walking) is much lower in neighborhoods that are majority Black or have high poverty compared to those that are White and highly affluent, reducing opportunities for exercise among minority and underserved populations. (681)Conderino SE, Feldman JM, Spoer B, Gourevitch MN, Thorpe LE. Social and Economic Differences in Neighborhood Walkability across 500 U.S. Cities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2021;61:394-401. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Because of the importance of the built environment to improving outcomes for patients with cancer, equal access to outdoor spaces is essential to improve health for everyone.

Health-related Quality of Life

Adverse physical effects are only a part of the impact that a cancer diagnosis can have on cancer survivors. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) offers a comprehensive view of the impact a disease and its treatment have on a patient’s physical, functional, psychological, social, and financial well-being (682)Oh H-JS, Menéndez ÁF, Santos VS, Martínez ÁR, Ribeiro FF, Vilanova-Trillo L, et al. Evaluating Health Related Quality of Life in Outpatients Receiving Anti-Cancer Treatment: Results from an Observational, Cross-Sectional Study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2021;19:245. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. HRQOL is becoming an important consideration in cancer care, the approval of new drugs, and prediction of long-term survival (683)Bottomley A, Pe M, Sloan J, Basch E, Bonnetain F, Calvert M, et al. Moving Forward toward Standardizing Analysis of Quality of Life Data in Randomized Cancer Clinical Trials. Clinical Trials 2018;15:624-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](684)Mierzynska J, Piccinin C, Pe M, Martinelli F, Gotay C, Coens C, et al. Prognostic Value of Patient-Reported Outcomes from International Randomised Clinical Trials on Cancer: A Systematic Review. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:e685-e98. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](685)Efficace F, Collins GS, Cottone F, Giesinger JM, Sommer K, Anota A, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes as Independent Prognostic Factors for Survival in Oncology: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Value in Health 2021;24:250-67. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Research has shown that HRQOL is lower for cancer survivors than individuals who have never had a cancer diagnosis or other type of chronic condition. Low HRQOL is exacerbated in cancer survivors who are pediatric (under 1 to 14 years of age) or adolescent and young adult (15-39 years of age) due to a range of factors (see sidebar on Survivorship Disparities in Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Patients). Cancer survivors that belong to medically underserved populations are at an elevated risk of worse HRQOL, which has been shown to increase the likelihood of cancer recurrence and mortality (686)Sitlinger A, Zafar SY. Health-Related Quality of Life: The Impact on Morbidity and Mortality. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2018;27:675-84. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](687)Park J, Rodriguez JL, O’Brien KM, Nichols HB, Hodgson ME, Weinberg CR, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes among Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer 2021;127:1114-25. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](688)Eichler M, Singer S, Hentschel L, Richter S, Hohenberger P, Kasper B, et al. The Association of Health-Related Quality of Life and 1-Year-Survival in Sarcoma Patients—Results of a Nationwide Observational Study (Prosa). Br J Can 2022;126:1346–1354. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Women cancer survivors who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) report increased depression, anxiety, and PTSD compared to heterosexual women (689)Schefter A, Thomaier L, Jewett P, Brown K, Stenzel AE, Blaes A, et al. Cross-Sectional Study of Psychosocial Well-Being among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Gynecologic CancerSurvivors. Cancer Reports 2022;5:e1461. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](690)Megan L. Hutchcraft AAT, Lauren Montemorano, and Joanne G. Patterson. Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life and Health Behaviors among Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Women Surviving Cancer from the 2013 to 2018 National Health Interview Survey. LGBT Health 2021;8:68-78. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A similar trend has been observed in gay men with prostate cancer, who reported worse mental health, greater fear of cancer recurrence, and general dissatisfaction with their medical care (691)Hart TL, Coon DW, Kowalkowski MA, Zhang K, Hersom JI, Goltz HH, et al. Changes in Sexual Roles and Quality of Life for Gay Men after Prostate Cancer: Challenges for Sexual Health Providers. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 2014;11:2308-17. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The disparity widens if the individuals are also Black or Hispanic, who experience poor overall health and physical health, and poor activity, explained by sociodemographic and access-to-care factors, further highlighting the key influence of intersectionality in cancer health disparities (692)Boehmer U, Jesdale BM, Streed Jr CG, Agénor M. Intersectionality and Cancer Survivorship: Sexual Orientation and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Physical and Mental Health Outcomes among Female and Male Cancer Survivors. Cancer 2022;128:284-91. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Sexual orientation is not a routinely discussed topic between physicians and survivors, which limits the ability to understand the cancer care needs of this population. There is increased interest in implementing standards to collect information on sexual and gender minorities (693)Griggs J, Maingi S, Blinder V, Denduluri N, Khorana AA, Norton L, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Position Statement: Strategies for Reducing Cancer Health Disparities among Sexual and Gender Minority Populations. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2203-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Routine assessment of sexual orientation would establish the need for sensitive and culturally appropriate health care discussions, foster healthy behaviors, and strengthen patient-physician relationships in addition to gathering data to assess cancer outcomes in sexual minorities (690)Megan L. Hutchcraft AAT, Lauren Montemorano, and Joanne G. Patterson. Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life and Health Behaviors among Lesbian, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Women Surviving Cancer from the 2013 to 2018 National Health Interview Survey. LGBT Health 2021;8:68-78. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Research into the health of SGM populations is necessary to improve outcomes, with nationally funded offices such as the NIH Sexual and Gender Minority Office launched in 2016 (694)National Institutes of Health – Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office. About SGMRO. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22]. providing resources to more clearly understand these needs.

Studies of breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer survivors who are Black report poorer quality of life, and physical and mental health compared to cancer survivors who are White (695)Samuel CA, Pinheiro LC, Reeder-Hayes KE, Walker JS, Corbie-Smith G, Fashaw SA, et al. To Be Young, Black, and Living with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review of Health-Related Quality of Life in Young Black Breast Cancer Survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2016;160:1-15. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](696)Pinheiro LC, Wheeler SB, Chen RC, Mayer DK, Lyons JC, Reeve BB. The Effects of Cancer and Racial Disparities in Health-Related Quality of Life among Older Americans: A Case-Control, Population-Based Study. Cancer 2015;121:1312-20. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](697)Claridy MD, Ansa B, Damus F, Alema-Mensah E, Smith SA. Health-Related Quality of Life of African-American Female Breast Cancer Survivors, Survivors of Other Cancers, and Those without Cancer. Quality of Life Research 2018;27:2067-75. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](698)Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, Berbaum ML, Manfredi C. Correlates of Quality of Life among African American and White Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nursing 2012;35:355-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Even when sociodemographic and psychosocial factors are accounted for, disparities in survivors’ mental health remain (698)Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, Berbaum ML, Manfredi C. Correlates of Quality of Life among African American and White Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nursing 2012;35:355-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Continued evaluation of quality of life in medically underserved populations and assessment of the contributing factors such as income, education, and stress are important to identify avenues for intervention. For instance, Black cancer survivors report increased social support and spirituality (697)Claridy MD, Ansa B, Damus F, Alema-Mensah E, Smith SA. Health-Related Quality of Life of African-American Female Breast Cancer Survivors, Survivors of Other Cancers, and Those without Cancer. Quality of Life Research 2018;27:2067-75. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] as well as communication among family members (699)Dickey SL, Matthews C, Millender E. An Exploration of Precancer and Post-Cancer Diagnosis and Health Communication among African American Prostate Cancer Survivors and Their Families. American Journal of Men’s Health 2020;14:1557988320927202. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] compared to those who are White. These data underscore the importance of culturally targeted regimens to improve quality of life for cancer survivors (698)Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, Berbaum ML, Manfredi C. Correlates of Quality of Life among African American and White Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nursing 2012;35:355-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](699)Dickey SL, Matthews C, Millender E. An Exploration of Precancer and Post-Cancer Diagnosis and Health Communication among African American Prostate Cancer Survivors and Their Families. American Journal of Men’s Health 2020;14:1557988320927202. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](700)Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and Quality of Life in Black Patients with Cancer Pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2018;56:390-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. To understand the myriad factors that contribute to these disparities, the NCI funded the Detroit Research on Cancer Survivors (ROCS) study which will look at cancer progression, recurrence, mortality, and quality of life of 5,560 African American cancer survivors across three counties surrounding Detroit, Michigan. The study seeks to identify how cancer type, genetics, social, psychological, and racial discrimination influence cancer survivorship in this group through interviews, medical records, and biospecimen collection; the study will also include survivors’ family members, to understand how a cancer diagnosis affects caregivers (701)National Institutes of Health. Nci Launces Study of African-American Cancer Survivors. [updated February 27, 2017, cited 2022 April 22]..

Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors experience lower HRQOL compared to other racial and ethnic groups (702)Samuel CA, Mbah OM, Elkins W, Pinheiro LC, Szymeczek MA, Padilla N, et al. Calidad De Vida: A Systematic Review of Quality of Life in Latino Cancer Survivors in the USA. Quality of Life Research 2020;29:2615-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](703)Graves KD, Jensen RE, Cañar J, Perret-Gentil M, Leventhal K-G, Gonzalez F, et al. Through the Lens of Culture: Quality of Life among Latina Breast Cancer Survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2012;136:603-13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Worse survival rates of colorectal, prostate, and breast cancers lead to this population experiencing higher psychosocial burden compared to NHW individuals (704)McNulty J, Kim S, Thurston T, Kim J, Larkey L. Interventions to Improve Quality of Life, Well Being and Cancer Care in Hispanic/Latino Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Literature Review. Oncology Nursing Forum 2016;43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](705)Ramirez AG, Gallion KJ, Perez A, Munoz E, Long Parma D, Moreno PI, et al. Improving Quality of Life among Latino Cancer Survivors: Design of a Randomized Trial of Patient Navigation. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2019;76:41-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, side effects of cancer treatment such as lymphedema may lower the physical and mental quality of life among these patients (706)Acebedo JC, Haas BK, Hermanns M. Breast Cancer–Related Lymphedema in Hispanic Women: A Phenomenological Study. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 2019;32:41-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Finally, food insecurity, a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food is experienced by 26 percent of Hispanic/Latino households and is more prevalent in Hispanics/Latinos as well as other underserved minorities with cancer (707)Gany F, Leng J, Ramirez J, Phillips S, Aragones A, Roberts N, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life of Food-Insecure Ethnic Minority Patients with Cancer. Journal of oncology practice 2015;11:396-402. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Higher rates of food insecurity experienced by patients and survivors of cancer that are Hispanic/ Latino as well as other underserved groups have been shown to lead to lower HRQOL compared with other races or ethnicities. Other research has shown that persistent food insecurity in cancer patients has led to lower treatment adherence (708)McDougall JA, Anderson J, Adler Jaffe S, Guest DD, Sussman AL, Meisner ALW, et al. Food Insecurity and Forgone Medical Care among Cancer Survivors. JCO Oncol Pract 2020;16:e922-e32. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is important for providers to screen for food insecurity in highly vulnerable groups in order to increase adherence to treatment, increase HRQOL, and improve patient outcomes.

Intervention strategies that address HRQOL in Hispanic/Latino populations, such as The National Latino Cancer Research Network and LIVESTRONG cancer navigation services patient navigation program, demonstrate the importance of providing culturally relevant patient navigation to improve quality of life in cancer survivors (705)Ramirez AG, Gallion KJ, Perez A, Munoz E, Long Parma D, Moreno PI, et al. Improving Quality of Life among Latino Cancer Survivors: Design of a Randomized Trial of Patient Navigation. Contemporary Clinical Trials 2019;76:41-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Avanzando Caminos (Leading Pathways): The Hispanic/Latino Cancer Survivorship Study is a 6-year study that aims to recruit 3,000 survivors of breast, colorectal, kidney, lung, prostate, stomach, and cervical cancers to understand the social, cultural, behavioral, psychosocial, biological, and medical influences during cancer survivorship. Studies like these are important in understanding recovery, disease burden, and quality of life after treatment and the unique biological and social burdens experienced by Hispanic/Latino cancer survivors (709)University of Texas Health. New $9.8 Million Study Is the 1st to Seek Full Understanding of the Latino Cancer Survivorship Journey. [updated May 4, 2021, cited 2022 April 22]..

American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) groups, which represents highly diverse communities with 560 federally recognized and 100 state tribes in the U.S., experience disparities in cancer survival rates and social and physical quality of life, and have the poorest 5-year survival rate from cancer of any racial group (710)Bastian TD, Burhansstipanov L. Sharing Wisdom, Sharing Hope: Strategies Used by Native American Cancer Survivors to Restore Quality of Life. JCO Global Oncology 2020:161-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](711)Burhansstipanov L, Dignan M, Jones KL, Krebs LU, Marchionda P, Kaur JS. A Comparison of Quality of Life between Native and Non-Native Cancer Survivors. Journal of Cancer Education 2012;27:106-13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](712)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Native American Priorities. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. Due to diversity among AI/AN tribal groups, spirituality characteristics are highly individualistic, and AI/AN cancer survivors have higher spiritual quality of life compared to those who belong to other races and ethnicities (711)Burhansstipanov L, Dignan M, Jones KL, Krebs LU, Marchionda P, Kaur JS. A Comparison of Quality of Life between Native and Non-Native Cancer Survivors. Journal of Cancer Education 2012;27:106-13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In one study of AN cancer survivors insight into navigating life after cancer, common themes pointed to the unique challenges survivors faced, such as balancing their responsibility to care for themselves while simultaneously embracing cultural values of selflessness (710)Bastian TD, Burhansstipanov L. Sharing Wisdom, Sharing Hope: Strategies Used by Native American Cancer Survivors to Restore Quality of Life. JCO Global Oncology 2020:161-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], which necessitates the study and use of culturally relevant approaches to cancer care and patient navigation such as those utilized by the Native American Cancer Survivors’ Support Network (NACES) (712)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Native American Priorities. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].(713)Burhansstipanov L, Krebs LU, Seals BF, Bradley AA, Kaur JS, Iron P, et al. Native American Breast Cancer Survivors’ Physical Conditions and Quality of Life. Cancer 2010;116:1560-71. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](714)Petereit D, Guadagnolo B, Wong R, Coleman C. Addressing Cancer Disparities among American Indians through Innovative Technologies and Patient Navigation: The Walking Forward Experience. Frontiers in Oncology 2011;1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Palliative Care

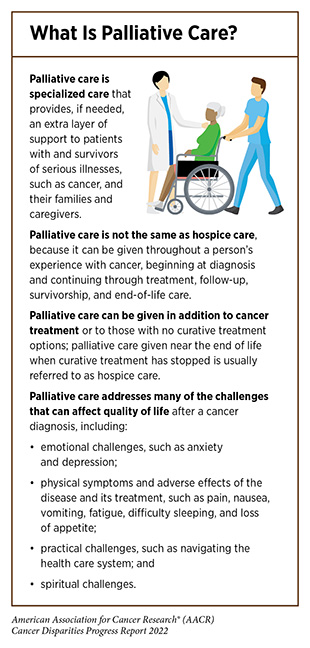

Palliative care is an approach to prevent or treat the symptoms and side effects of any disease, including cancer, by addressing the physical, psychological, financial, social, and spiritual needs that arise from the disease and associated treatments (see sidebar on What Is Palliative Care?). Palliative care is facilitated by a multidisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, dieticians, pharmacists, therapists, spiritual leaders, and social workers and has been shown to improve quality of life for patients, families, and caregivers (715)Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, Wenk R, Ali Z, Bhatnaghar S, et al. Redefining Palliative Care—a New Consensus-Based Definition. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2020;60:754-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Despite the advantages of palliative care, there are disparities (716)Elk R, Felder TM, Cayir E, Samuel CA. Social Inequalities in Palliative Care for Cancer Patients in the United States: A Structured Review. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 2018;34:303-15. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] in utilization by racial and ethnic minorities, SGM populations (717)Haviland K, Burrows Walters C, Newman S. Barriers to Palliative Care in Sexual and Gender Minority Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Health & Social Care in the Community 2021;29:305-18. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and those living in geographically remote areas (718)Bakitas MA, Elk R, Astin M, Ceronsky L, Clifford KN, Dionne-Odom JN, et al. Systematic Review of Palliative Care in the Rural Setting. Cancer Control 2015;22:450-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](719)Cancer Network. Challenges of Rural Cancer Care in the United States. [updated September 15, 2015, cited 2022 April 22].. Unfortunately, most studies examining palliative care in medically underserved populations focus on the end-of-life care and not care during cancer treatment or survivorship. Additional focus needs to be given to identifying the unique needs of cancer patients from medically underserved groups, developing innovative methods to overcome barriers, and implementing policies that provide equitable care (720)Polite BN, Adams-Campbell LL, Brawley OW, Bickell N, Carethers JM, Flowers CR, et al. Charting the Future of Cancer Health Disparities Research: A Position Statement from the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2017;67:353-61. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] during the chronic phase of cancer survivorship (see sidebar on Phases of Cancer Survivorship).

End-of-life care is one component of palliative care that places emphasis on improving patient comfort and quality of life through management of pain, psychological burden, and medical events. Unfortunately, there are disparities in access to appropriate end-of-life care services. For instance, over 70 percent of patients with multiple myeloma who are in the final stages of the disease develop bone lesions and related skeletal events, leading to pain. Palliative radiotherapy is an effective treatment to reduce pain. However, based on a recent study, Black patients were 13 percent less likely to receive this treatment compared to NHW patients (721)Fossum CC, Navarro S, Farias AJ, Ballas LK. Racial Disparities in the Use of Palliative Radiotherapy for Black Patients with Multiple Myeloma in the United States. Leukemia & Lymphoma 2021;62:3235-43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Management of care during terminal stages of cancer comes with tremendous mental and physical challenges for patients, caregivers, family, and friends. Current guidelines during end-of-life care favor highest quality of life over intense treatment interventions, which can be aggressive, invasive, and expensive (722)Bickel KE, McNiff K, Buss MK, Kamal A, Lupu D, Abernethy AP, et al. Defining High-Quality Palliative Care in Oncology Practice: An American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Guidance Statement. Journal of Oncology Practice 2016;12:e828-e38. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](723)Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Alesi ER, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. Integration of Palliative Care into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96-112. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](724)Deeb S, Chino FL, Diamond LC, Tao A, Aragones A, Shahrokni A, et al. Disparities in Care Management During Terminal Hospitalization among Adults with Metastatic Cancer from 2010 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2125328-e. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, it has been shown that patients from racial and ethnic minorities and those on Medicare or Medicaid that have metastatic cancers and are receiving end of life care are more likely to receive more aggressive, higher cost medical interventions that are not beneficial (724)Deeb S, Chino FL, Diamond LC, Tao A, Aragones A, Shahrokni A, et al. Disparities in Care Management During Terminal Hospitalization among Adults with Metastatic Cancer from 2010 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2125328-e. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. More research is needed to understand why patients belonging to these groups are more likely to receive this type of care and to develop prospective interventions that can be implemented in the future.

Financial Toxicity

Financial toxicity refers to the detrimental effects experienced by cancer survivors and their family members caused by the financial strain after a cancer diagnosis. Estimates indicate that out-of-pocket costs for cancer care are higher than for any other chronic illness (743)Bernard DSM, Farr SL, Fang Z. National Estimates of out-of-Pocket Health Care Expenditure Burdens among Nonelderly Adults with Cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2821-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and at least 50 percent of patients with cancer report financial difficulties irrespective of cancer type or treatment regimen (744)Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR. Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2016;109. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](745)de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, Blinder V, Araújo FS, Hlubocky FJ, et al. Measuring Financial Toxicity as a Clinically Relevant Patient-Reported Outcome: The Validation of the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (Cost). Cancer 2017;123:476-84. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These financial strains lead to financial coping behaviors including taking medications less frequently (e.g. skipping doses, taking less medication than prescribed, or not filling a prescription); taking on debt; reduced follow-up care; and decreased preventative services, all of which increase cancer-related mortality (746)Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, Chino F, Samsa GP, Altomare I, et al. Patient-Oncologist Cost Communication, Financial Distress, and Medication Adherence. Journal of Oncology Practice 2014;10:162-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](747)Doherty M, Gardner D, Finik J. The Financial Coping Strategies of US Cancer Patients and Survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer 2021;29:5753-62. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](748)Gu C, Jewett PI, Yabroff KR, Vogel RI, Parsons HM, Gangnon RE, et al. Forgoing Physician Visits Due to Cost: Regional Clustering among Cancer Survivors by Age, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity. J Cancer Surviv 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](749)Bridgette Thom CB. The Impact of Financial Toxicity on Psychological Well-Being, Coping Self-Efficacy, and Cost-Coping Behaviors in Young Adults with Cancer. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 2019;8:236-42. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](750)Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality among Patients with Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:980-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The burden of cancer disproportionately affects those who are poor or are living in poverty (see Cancer Health Disparities Among Other Medically Underserved Populations). Additionally, chronic diseases such as cancer have consistently high costs of care and unfairly impact populations from low SES pushing them deeper into poverty. To that end, low-income Americans have difficulty paying for cancer care, even when insured. With increasing enrollment of many U.S. workers in high-deductible health insurance plans (751)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. High-Deductible Health Plan Enrollment among Adults Aged 18–64 with Employment-Based Insurance Coverage. [updated August 9, 2018, cited 2022 April 22]., which offer lower up-front costs in exchange for high deductibles (anywhere from $2,500 to $5,000) (752)Yousuf Zafar S. Financial Toxicity of Cancer Care: It’s Time to Intervene. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2015;108. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], even insured patients with cancer may struggle with debt related to treatment and follow up care. In fact, roughly 50% of Americans are not able to afford to pay their deductibles using savings (752)Yousuf Zafar S. Financial Toxicity of Cancer Care: It’s Time to Intervene. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2015;108. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, the inability to afford treatments or accumulation of debt leads to the increased likelihood of bankruptcy among cancer survivors. Furthermore, finding a new job or returning to a previous job is more difficult after any cancer diagnosis (753)Meernik C, Sandler DP, Peipins LA, Hodgson ME, Blinder VS, Wheeler SB, et al. Breast Cancer–Related Employment Disruption and Financial Hardship in the Sister Study. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 2021;5. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](754)Hallgren E, Ayers BL, Moore R, Purvis RS, McElfish PA, Maraboyina S, et al. Facilitators and Barriers to Employment for Rural Women Cancer Survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2022 Feb 10. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], further straining survivors financially (755)Mols F, Tomalin B, Pearce A, Kaambwa B, Koczwara B. Financial Toxicity and Employment Status in Cancer Survivors. A Systematic Literature Review. Supportive Care in Cancer 2020;28:5693-708. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Those who experience financial toxicity are also less likely to enroll in clinical trials (756)Chino F, Zafar SY. Financial Toxicity and Equitable Access to Clinical Trials. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2019:11-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](757)Winkfield KM, Phillips JK, Joffe S, Halpern MT, Wollins DS, Moy B. Addressing Financial Barriers to Patient Participation in Clinical Trials: ASCO Policy Statement. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:3331-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], preventing access to potentially lifesaving treatments and furthering the low participation of medically underserved populations (see Disparities in Cancer Clinical Trial Participation).

Individuals who belong to medically underserved groups including racial and ethnic minorities, those who live in rural areas, and/or those who are elderly are at a higher risk of experiencing financial toxicity as a result of a cancer diagnosis (143)Panzone J, Welch C, Pinkhasov R, Jacob JM, Shapiro O, Basnet A, et al. The Influence of Race on Financial Toxicity among Cancer Patients. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:1525. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](759)Jagsi R, Pottow JAE, Griffith KA, Bradley C, Hamilton AS, Graff J, et al. Long-Term Financial Burden of Breast Cancer: Experiences of a Diverse Cohort of Survivors Identified through Population-Based Registries. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1269-76. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](760)Wheeler SB, Spencer JC, Pinheiro LC, Carey LA, Olshan AF, Reeder-Hayes KE. Financial Impact of Breast Cancer in Black Versus White Women. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1695-701. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](761)Shah K, Zafar SY, Chino F. Role of Financial Toxicity in Perpetuating Health Disparities. Trends in Cancer 2022;8:266-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Compared to 44.5 percent of NHWs, 68 percent of African Americans and 58 percent of Hispanics reported experiencing financial hardships one year after cancer diagnosis (762)Pisu M, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, Drentea P, Ashing KT, Fouad M, et al. Economic Hardship of Minority and Non-Minority Cancer Survivors 1 Year after Diagnosis: Another Long-Term Effect of Cancer? Cancer 2015;121:1257-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In a study that examined the effects of cancer on financial wellness, both Black and Hispanic groups reported being negatively impacted financially twice as often as White individuals (759)Jagsi R, Pottow JAE, Griffith KA, Bradley C, Hamilton AS, Graff J, et al. Long-Term Financial Burden of Breast Cancer: Experiences of a Diverse Cohort of Survivors Identified through Population-Based Registries. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1269-76. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This led to increased use of financial coping behaviors like skipping medications (747)Doherty M, Gardner D, Finik J. The Financial Coping Strategies of US Cancer Patients and Survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer 2021;29:5753-62. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Among rural populations, such as those residing in the Appalachian region of the eastern United States, two thirds of cancer survivors reported financial distress (763)Vanderpool RC, Chen Q, Johnson MF, Lei F, Stradtman LR, Huang B. Financial Distress among Cancer Survivors in Appalachian Kentucky. Cancer Reports 2020;3:e1221. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Compared to NHWs, elderly Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander were less likely to be able to pay medical bills, more likely to experience psychological distress about paying bills, and more likely to delay or forgo medical care due to cost (764)Li C, Narcisse M-R, McElfish PA. Medical Financial Hardship Reported by Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Cancer Survivors Compared with Non-Hispanic Whites. Cancer 2020;126:2900-14. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Even after treatment, cancer survivors especially those from racial and ethnic minorities, experience difficulties in obtaining health and life insurance. Compared to NHWs, Black cancer survivors were three to five times more likely to be denied health insurance (765)Panzone J, Welch C, Morgans A, Bhanvadia SK, Mossanen M, Shenhav-Goldberg R, et al. Association of Race with Cancer-Related Financial Toxicity. JCO Oncology Practice 2022;18:e271-e83. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], while Hispanic cancer survivors were twice as likely to be denied health insurance (766)Lent AB, Garrido CO, Baird EH, Viela R, Harris RB. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health and Life Insurance Denial Due to Cancer among Cancer Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022;19:2166. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Lack of, or insufficient, health insurance coverage can further increase mortality among racial and ethnic minorities from side effects of cancer, such as cardiovascular disease, which is increased in NHB cancer survivors (767)Shi T, Jiang C, Zhu C, Wu F, Fotjhadi I, Zarich S. Insurance Disparity in Cardiovascular Mortality among Non-Elderly Cancer Survivors. Cardio-Oncology 2021;7:11. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Combating financial toxicity for cancer survivors must occur at multiple levels such as lowering of drug prices, implementation of financial planners, evaluation of high-deductible insurance plans, and practical decision-making about what treatments are necessary such as through the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choose Wisely campaign. This campaign helps patients choose treatment that has been proven to be effective and avoid unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures. In order to navigate the financial burdens of cancer care, the use of patient navigators and patient advocates, and discussions with the health care team, will be necessary to reduce financial toxicity, which disproportionately affects medically underserved groups.

Adherence to Follow-Up Care

The cancer experience does not end at the completion of the initial treatment plan, as 60 percent of adults diagnosed with cancer are expected to become long-term cancer survivors (768)DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, et al. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2014;64:252-71. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Follow-up care for cancer survivors includes developing a survivorship care plan with the health care team, monitoring for signs of cancer recurrence, managing the long- and late-term side effects of treatments, and monitoring overall health. Due to the uniqueness of each individual, their cancer, and their treatment, the needs of each survivor are highly complex and variable, which creates challenges to effective follow-up care.

Following completion of the treatment, continuity of care is an important component of a successful transition to living with and beyond cancer. This includes the coordinated and uninterrupted care of a patient’s physical, mental, and social needs. Fragmentation of care can lead to duplicated services which can increase costs; reduce patient-clinician trust and communication; and decrease a patient’s satisfaction with care and quality of life (769)Plate S, Emilsson L, Söderberg M, Brandberg Y, Wärnberg F. High Experienced Continuity in Breast Cancer Care Is Associated with High Health Related Quality of Life. BMC Health Services Research 2018;18:127. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](770)Chen Y-Y, Hsieh C-I, Chung K-P. Continuity of Care, Followup Care, and Outcomes among Breast Cancer Survivors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019;16:3050. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](771)Aubin M, Vézina L, Verreault R, Simard S, Hudon É, Desbiens J-F, et al. Continuity of Cancer Care and Collaboration between Family Physicians and Oncologists: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. The Annals of Family Medicine 2021;19:117. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As one example, a higher continuity of care benefited Black prostate cancer survivors over two years after the conclusion of treatment and was associated with fewer emergency room visits, lower cost, and lower all-cause mortality compared to White cancer survivors (772)Chhatre S, Malkowicz SB, Jayadevappa R. Continuity of Care in Acute Survivorship Phase, and Short and Long-Term Outcomes in Prostate Cancer Patients. The Prostate 2021;81:1310-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The success of continuity of care immediately following treatment in improving outcomes, especially in medically underserved groups, highlights the importance of incorporating such regimens into the current standard of care.

Follow-up care can be delayed because of lack of insurance and out-of-pocket costs, transportation and language barriers, scheduling challenges, and childcare issues, especially in groups at risk of experiencing difficulties related to these factors such as those in rural communities or immigrants (774)Milam JE, Meeske K, Slaughter RI, Sherman-Bien S, Ritt-Olson A, Kuperberg A, et al. Cancer-Related Follow-up Care among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Childhood Cancer Survivors: The Project Forward Study. Cancer 2015;121:605-13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](775)Rosales M, Ashing K, Napoles A. Quality of Cancer Follow-up Care: A Focus on Latina Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2014;8:364-71. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](776)Jiang C, Yabroff KR, Deng L, Wang Q, Perimbeti S, Shapiro CL, et al. Self-Reported Transportation Barriers to Health Care among US Cancer Survivors. JAMA Oncol 2022;8:775-778. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, breast cancer survivors who were Black reported increased difficulty in accessing follow-up care due to one or more of these factors at a higher rate than survivors who were White (777)Palmer NRA, Weaver KE, Hauser SP, Lawrence JA, Talton J, Case LD, et al. Disparities in Barriers to Follow-up Care between African American and White Breast Cancer Survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer 2015;23:3201-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Those living in rural areas are less likely to continue follow-up care because of greater distance from large research hospitals, which are usually located in metropolitan areas. This creates barriers for rural residents, such as those living in Appalachia, Mississippi Delta, and Rocky Mountain regions of the United States; for AI/AN communities that live on reservations; or for those in rural communities with limited transportation options. Long travel times compounded by financial strains lead to a reluctance to travel to specialists, opting for local primary care providers who may lack experience and/or access to state-of-the-art facilities and adequate knowledge about frequency of surveillance testing for cancer recurrence (778)Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kutner JS, Najita JS, et al. Caring for Cancer Survivors. Cancer 2009;115:4409-18. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Transfer of care to primary care physicians from oncologists can often create gaps in follow-up care for doctors and patients (779)Schootman M, Homan S, Weaver KE, Jeffe DB, Yun S. The Health and Welfare of Rural and Urban Cancer Survivors in Missouri. Preventing Chronic Disease 2013;10:E152. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](780)Blanch-Hartigan D, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Smith T, Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, et al. Provision and Discussion of Survivorship Care Plans among Cancer Survivors: Results of a Nationally Representative Survey of Oncologists and Primary Care Physicians. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1578-85. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Recommendations to improve transfer of care among patients living in remote areas include the use of telehealth strategies. Although telehealth is highly effective, lack of access to high-speed Internet and computers can limit access to telehealth for medically underserved groups and could exacerbate disparities. Recruitment and retention of oncology providers in rural hospitals through incentives, including loan repayments are also important ways to improve care in rural areas for patients after treatment (781)ASCO. Asco Announces New Program Designed to Increase Workforce Diversity and Reduce Cancer Care Disparities. Journal of Oncology Practice 2009;5:315-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Impact of COVID-19 on Disparities in Cancer Survivorship

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a more severe impact on mental and physical health of cancer survivors compared to those without a history of cancer (782)Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, et al. Clinical Impact of COVID-19 on Patients with Cancer (Ccc19): A Cohort Study. The Lancet 2020;395:1907-18. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](783)Zhao F, Henderson TO, Cipriano TM, Copley BL, Liu M, Burra R, et al. The Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 on the Quality of Life and Treatment Disruption of Patients with Breast Cancer in a Multiethnic Cohort. Cancer 2021;127:4072-80. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](784)Ciazynska M, Pabianek M, Szczepaniak K, Ulanska M, Skibinska M, Owczarek W, et al. Quality of Life of Cancer Patients During Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Psycho-Oncology 2020;29:1377-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](785)Koinig KA, Arnold C, Lehmann J, Giesinger J, Köck S, Willenbacher W, et al. The Cancer Patient’s Perspective of COVID-19-Induced Distress—a Cross-Sectional Study and a Longitudinal Comparison of Hrqol Assessed before and During the Pandemic. Cancer Medicine 2021;10:3928-37. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](786)Katz AJ, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Kubik R, Chen RC. Evaluation of Telemedicine Use among US Patients with Newly Diagnosed Cancer by Socioeconomic Status. JAMA Oncol 2022;8:161-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The pandemic has increased social isolation, financial stress, and food insecurity, as well as timely access to routine follow-up care. As many of these factors are commonly known mechanisms for disparities in cancer survivorship, COVID-19 has disproportionately affected cancer survivors belonging to racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations. Furthermore, Black, Hispanic, and AI/AN individuals have experienced a higher burden of COVID-19 compared to NHW individuals. These compounding factors place racial and ethnic minority survivors at risk of negative outcomes necessitating increased support for these groups through and beyond the pandemic. AACR has outlined many of these challenges in the AACR Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Research and Patient Care with a Call to Action to bolster access to health care services, like telehealth, which has been less accessible to minorities but can potentially address health care disparities (786)Katz AJ, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Kubik R, Chen RC. Evaluation of Telemedicine Use among US Patients with Newly Diagnosed Cancer by Socioeconomic Status. JAMA Oncol 2022;8:161-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](787)Jewett PI, Vogel RI, Ghebre R, Hui JYC, Parsons HM, Rao A, et al. Telehealth in Cancer Care During COVID-19: Disparities by Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Residential Status. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2022;16:44-51. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Paving the Way for Health Equity in Cancer Survivorship

The disparities in various aspects of cancer survivorship as highlighted in this chapter necessitate a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach to address the deficiencies experienced by underserved groups. This includes researchers, health care systems, professional organizations, insurance groups, and care teams working together to meet the specific needs of the community and the patient.

Community-centered approaches that meet patients where they are, are required if we are to better understand the challenges faced by cancer survivors who belong to racial and ethnic minorities and underserved populations. Patient advocates, such as Sandra Morales and Marlena Murphy, who themselves are often cancer survivors and support those living with and through cancer, are uniquely positioned to bridge a critical gap between survivors and researchers. Patient advocates have immense social capital within their communities because they understand the unique needs and challenges within the community; this can help inform research questions and clinical study designs. Patient advocates can also help disseminate new information gleaned from research studies into the community so that it is readily accessible and favorably received. Organizations such as Turning Point and Guiding Researchers and Advocates to Scientific Partnerships (GRASP) bridge the gap by bringing together all stakeholders including researchers, advocates, and survivors. Utilization of patient advocates is necessary to reduce health disparities, voice community concerns, increase research of underserved groups, increase survival, increase quality of life, and reduce financial strain on survivors.

Patient navigators are individuals dedicated to assisting patients with cancer, survivors, family, and caregivers by facilitating and navigating through the health care system for access to timely and quality care. Utilization of patient navigation has been shown to benefit patients across the cancer care continuum, especially in medically underserved population groups, and to reduce the overall costs associated with cancer (788)Kline RM, Rocque GB, Rohan EA, Blackley KA, Cantril CA, Pratt-Chapman ML, et al. Patient Navigation in Cancer: The Business Case to Support Clinical Needs. Journal of Oncology Practice 2019;15:585-90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](789)Dixit N, Rugo H, Burke NJ. Navigating a Path to Equity in Cancer Care: The Role of Patient Navigation. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2021:3-10. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](790)The Cancer Center Cessation Initiative Diversity E, and Inclusion Working Group Members. Use of Community Health Workers and Patient Navigators to Improve Cancer Outcomes among Patients Served by Federally Qualified Health Centers: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Equity 2017;1:61-76. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In fact, the first patient navigation program in the U.S. was designed specifically to address racial disparities of breast cancer screening and follow-up in Black women, which led to a 70 percent increase in 5-year survival in this group (791)Oluwole SF, Ali AO, Adu A, Blane BP, Barlow B, Oropeza R, et al. Impact of a Cancer Screening Program on Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis in a Medically Underserved Urban Community. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:180-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](792)Freeman HP. Patient Navigation: A Community Based Strategy to Reduce Cancer Disparities. Journal of Urban Health 2006;83:139-41. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Recognition of the benefits of patient navigators on health outcomes has led to legislative efforts to increase access to patient navigation including the Patient Navigation Outreach and Chronic Disease Prevention Act in 2005 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010, the latter of which requires each state health insurance exchange to establish a navigator program.

To further increase the use of patient navigators, the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) required all organizations accredited by the CoC to have a patient navigation program by 2015. Despite this requirement, there is high variability in the organization and training of patient navigators in the United States, leading to heterogeneous navigation (793)Ustjanauskas AE, Bredice M, Nuhaily S, Kath L, Wells KJ. Training in Patient Navigation:A Review of the Research Literature. Health Promotion Practice 2016;17:373-81. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]; for instance, navigators can be classified as either health care or non-health care workers leading to confusion surrounding their credentials. Additionally, there is often confusion abou(794)Pratt-Chapman M, Willis A. Community Cancer Center Administration and Support for Navigation Services. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 2013;29:141-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]t coverage and financial benefits of patient navigator services through Medicare, Medicaid, and private/commercial insurers (794)Pratt-Chapman M, Willis A. Community Cancer Center Administration and Support for Navigation Services. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 2013;29:141-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Broad implementation of patient navigators to assist all patients with cancer will require standardization guidelines and population-specific training, support from government and health care providers, and more universal access through implementation of telehealth (see Sustainably Supporting Patient Navigators and Community Health Workers).

A key to charting an equitable path forward for cancer survivors who belong to medically underserved populations is the use of community-based tailored solutions that meet the specific needs of every patient and include patient advocates and patient navigators as key partners. Such an approach will help implement strategies that address the specific social, psychological, medical, and physical needs of the patient while tying in cultural norms and perceptions, ultimately increasing quality of life; bolstering adherence to follow-up care; identifying financial concerns; providing equitable health care; and reducing the overall cost of cancer care (795)Walls M, Chambers R, Begay M, Masten K, Aulandez K, Richards J, et al. Centering the Strengths of American Indian Culture, Families and Communities to Overcome Type 2 Diabetes. Frontiers in Public Health 2022;9:788285. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].