Disparities in Clinical Research and Cancer Treatment

In this section, you will learn:

- Clinical trials establish whether new cancer treatments are safe and effective for everyone who will use them if they are approved; the substantial lack of sociodemographic diversity among clinical trial participants represents a major barrier to advancing cancer care for the entire patient population.

- Achieving cancer health equity through access to care must include equitable access to participation in clinical research opportunities. Physicians must play an active role in this effort, by ensuring that all patients are offered appropriate clinical trial options, regardless of race/ethnicity or socioeconomics.

- Improved diversity among clinical trial participants requires attention to study design regarding accrual sites and outreach; involvement of a diverse trial workforce and patient navigators; use of culturally tailored patient education materials; and minimizing the costs associated with trial participation, such as those related to frequency of clinic visits.

- Despite many advances in the main pillars of cancer treatment, patients from racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations are less likely to receive the standard of care recommended for the type and stage of cancer with which they have been diagnosed.

- Several recent studies have shown that racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes for several types of cancer can be eliminated if every patient has equitable access to standard treatment.

- Clinical interventions that utilize patient navigation and community engagement can reduce disparities in cancer treatment among underserved groups and potentially improve outcomes for all patients with cancer.

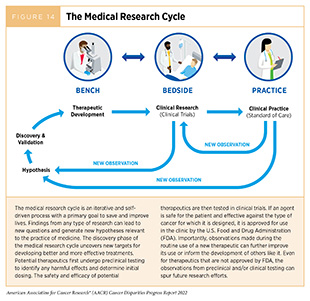

Medical research is an iterative process that is set in motion when a discovery with the potential to affect the practice of medicine or public health is made in any area of research or clinical practice (Figure 14). One way that researchers build on a discovery is by asking questions that can be tested through experiments in a wide range of models that mimic healthy and diseased conditions. Results from these experiments can lead to the identification of potential therapeutic targets, or biomarkers—cellular and molecular characteristics measurable in tissue and/or bodily fluid by which normal and/or abnormal processes can be recognized and/or monitored. They also can feed back into the medical research cycle by providing new discoveries that lead to more questions or hypotheses.

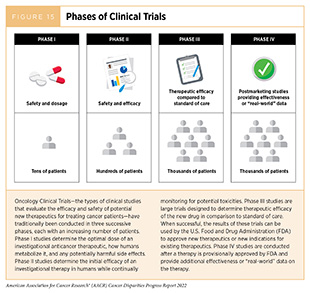

Once a potential therapeutic target is identified, it takes many more years of preclinical research before a candidate therapeutic is developed and ready for testing in clinical trials. During this time, several drug candidates are rigorously tested to identify any potential toxicity and to determine the appropriate doses and dosing schedules for testing in the first clinical trial. There are many types of clinical trials, each designed to answer different research questions (see sidebar on Types of Clinical Studies). All clinical trials are reviewed and approved by institutional review boards before they can begin and are monitored throughout their duration. Clinical trials testing the safety and efficacy of candidate anticancer therapeutics have traditionally been done in three successive phases (Figure 15).

Disparities in Cancer Clinical Trial Participation

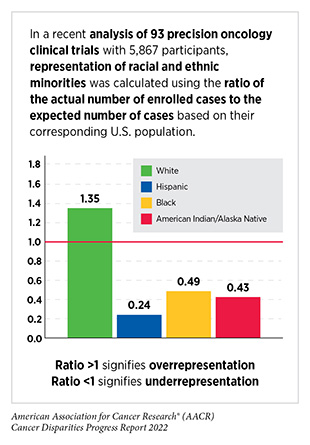

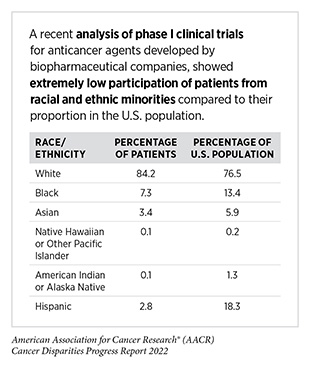

While researchers are continually identifying and implementing new ways of designing, conducting, and reviewing clinical trials that are yielding advances in patient care, there are still numerous opportunities for improvements. The most pressing challenges that need to be urgently addressed are low participation in clinical trials, in particular, among individuals living in rural areas, adolescents and young adults, and the elderly, as well as the lack of representation from racial and ethnic minorities (see sidebar on Disparities in Clinical Trial Participation). Participation of racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations in clinical trials is critical to accurately determine the efficacy as well as potential toxicities of new treatments in these populations. Diversity among participants is even more vital during evaluation of cancer types with a disparately higher burden in racial or ethnic minorities, as well as during evaluation of cutting-edge precision medicine, e.g., molecularly targeted therapeutics or immunotherapeutics, because these treatments are closely tied to the unique characteristics of an individual’s cancer, immune system, and lifestyle, among other factors. Enrollment of diverse participants in clinical trials, as well as the race- and ethnicity-specific reporting of the benefits and potential risks, can enable a comprehensive understanding of ancestry-related differences in cancer biology, disease biomarkers, or treatment responses including adverse events and ensure that newly approved anticancer agents can be safely used in the real-world patient population for whom these treatments are ultimately intended.

The NIH Revitalization Act was implemented in 1993 to improve the representation of women and minority populations in clinical trials. Since then, additional initiatives have been put forward by federal organizations including FDA and NCI to address the lack of diversity in clinical trials. Unfortunately, despite these efforts, minority participation in clinical trials and race and ethnicity reporting have improved only minimally (496)Javier-DesLoges J, Nelson TJ, Murphy JD, McKay RR, Pan E, Parsons JK, et al. Disparities and Trends in the Participation of Minorities, Women, and the Elderly in Breast, Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials. Cancer 2022;128:770-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](497)Herremans KM, Riner AN, Winn RA, Trevino JG. Diversity and Inclusion in Pancreatic Cancer Clinical Trials. Gastroenterology 2021;161:1741-6.e3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](498)Jayakrishnan T, Aulakh S, Baksh M, Nguyen K, Ailawadhi M, Samreen A, et al. Landmark Cancer Clinical Trials and Real-World Patient Populations: Examining Race and Age Reporting. Cancers 2021;13:5770. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and certain segments of the U.S. population continue to be severely underrepresented in clinical research. A recent analysis of FDA’s Drug Trials Snapshots website, which was created to improve diversity and transparency of pivotal clinical trials of newly approved drugs, indicated that since the implementation of the initiative fewer than 20 percent of therapeutics included data regarding benefits or side effects among Black patients (499)Angela K. Green NT, Jennifer J. Hsu, Nancy L. Yu, Peter B. Bach, and Susan Chimonas. Despite the Fda’s Five-Year Plan, Black Patients Remain Inadequately Represented in Clinical Trials for Drugs. Health Affairs 2022;41:368-74. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A separate assessment of patient enrollment in clinical trials that led to FDA approvals of 75 new anticancer agents between 2014 and 2018 indicated that Black patients were significantly underrepresented in breast, prostate, lung, and blood cancer clinical trials relative to their disease burden in the U.S. while White patients were overrepresented (500)Al Hadidi S, Mims M, Miller-Chism CN, Kamble R. Participation of African American Persons in Clinical Trials Supporting U.S. Food and Drug Administration Approval of Cancer Drugs. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:320-2. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similar trends have been noted among early-phase clinical trials (501)Camidge DR, Park H, Smoyer KE, Jacobs I, Lee LJ, Askerova Z, et al. Race and Ethnicity Representation in Clinical Trials: Findings from a Literature Review of Phase I Oncology Trials. Future Oncology 2021;17:3271-80. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation

Numerous studies have investigated the existing barriers that limit participation of racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations in cancer clinical trials. These data indicate a range of structural barriers and societal injustices that operate at individual (patient and health care provider) and systemic (health care system) levels (512)Kahn JM, Gray DM, 2nd, Oliveri JM, Washington CM, DeGraffinreid CR, Paskett ED. Strategies to Improve Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Clinical Trials. Cancer 2022;128:216-21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The individual-level barriers for patients include lack of awareness of clinical trials, limited health literacy, and mistrust of the health care system, as well as financial barriers such as costs of cancer treatment and medication, transportation, child care, lost work, and inadequate or complete lack of insurance, among others. A recent study that assessed the clinical and nonclinical barriers to participation of Black patients in cancer clinical trials at a safety-net hospital identified lack of understanding of cancer clinical trials and perceptions and fears of cancer clinical trials as two prominent themes (513)Hernandez ND, Durant R, Lisovicz N, Nweke C, Belizaire C, Cooper D, et al. African American Cancer Survivors’ Perspectives on Cancer Clinical Trial Participation in a Safety-Net Hospital: Considering the Role of the Social Determinants of Health. J Cancer Educ 2021;10.1007/s13187-021-01994-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Most participants stated that their health care providers never informed them of clinical trials, and many reported fear and mistrust of the health care system as a barrier to clinical trial participation. It is important to note that safety-net practices provide a disproportionately larger share of care to racial and ethnic minorities, as well as low-income and/or uninsured individuals, among other medically underserved populations. Thus, addressing barriers to clinical trial participation at these facilities is vital if we are to reduce cancer health disparities. Careful consideration must be given to the adverse influences of SDOH, including poverty, food insecurity, housing insecurity, and psychosocial stressors (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities), while approaching interventions for patients receiving care at safety-net hospitals. In this regard, it should be noted that among cancer patients participating in clinical trials, those living in areas with high socioeconomic deprivation are still at an increased risk of worse outcomes (514)Unger JM, Moseley AB, Cheung CK, Osarogiagbon RU, Symington B, Ramsey SD, et al. Persistent Disparity: Socioeconomic Deprivation and Cancer Outcomes in Patients Treated in Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:1339-48. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Future research should examine how to eliminate additional sources of disparities that are not mitigated even after equal access to clinical trials.

Lack of health literacy including limited understanding of clinical trials has been reported as a barrier for participation in clinical trials (513)Hernandez ND, Durant R, Lisovicz N, Nweke C, Belizaire C, Cooper D, et al. African American Cancer Survivors’ Perspectives on Cancer Clinical Trial Participation in a Safety-Net Hospital: Considering the Role of the Social Determinants of Health. J Cancer Educ 2021;10.1007/s13187-021-01994-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Evaluation of barriers among Hispanic patients indicates that poor understanding of the purpose of a clinical trial, poor communication with health care providers, and fear of uncertainty over experimental treatment may adversely affect their enrollment in clinical trials (515)Overcoming Barriers for Latinos on Cancer Clinical Trials. [updated December 13, 2019, cited 2022 April 22].. Low health literacy has also been reported as a barrier to parents in making informed decisions for their child’s participation in clinical research (516)Aristizabal P, Ma AK, Kumar NV, Perdomo BP, Thornburg CD, Martinez ME, et al. Assessment of Factors Associated with Parental Perceptions of Voluntary Decisions About Child Participation in Leukemia Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e219038. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Financial costs are another key patient-level barrier to clinical trial enrollment. According to a recent survey of 213 cancer patients enrolled in early-phase clinical trials, half of the respondents reported out-of-pocket costs of at least 1,000 US dollars every month (517)Huey RW, George GC, Phillips P, White R, Fu S, Janku F, et al. Patient-Reported out-of-Pocket Costs and Financial Toxicity During Early-Phase Oncology Clinical Trials. The Oncologist 2021;26:588-96. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. More than half of participants reported unanticipated medical and nonmedical expenses including for travel and housing. Racial and ethnic minority individuals as well as those with lower income experienced disproportionately higher unanticipated medical costs (517)Huey RW, George GC, Phillips P, White R, Fu S, Janku F, et al. Patient-Reported out-of-Pocket Costs and Financial Toxicity During Early-Phase Oncology Clinical Trials. The Oncologist 2021;26:588-96. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Transportation difficulties including lack of free parking in urban locations are a known barrier to minority participation in clinical research (518)Rogers CR, Matthews P, Brooks E, Duc NL, Washington C, McKoy A, et al. Barriers to and Facilitators of Recruitment of Adult African American Men for Colorectal Cancer Research: An Instrumental Exploratory Case Study. JCO Oncology Practice 2021;17:e686-e94. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It has been reported that cancer patients may face substantial nonmedical costs through parking fees at NCI-designated cancer treatment centers, especially in cities with a high cost of living (519)Lee A, Shah K, Chino F. Assessment of Parking Fees at National Cancer Institute–Designated Cancer Treatment Centers. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1295-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The high financial burden for patients, especially those from minority and underserved populations, may deter these patients from participating in clinical research trials and must be addressed during the design and implementation of these studies.

Many barriers exist at the provider level including lack of knowledge of clinical trials; implicit biases among health care providers; lack of dedicated staff to serve minority populations; and lack of cultural competence and appropriate communication skills, among other factors. Patients ages 15 to 39, who are collectively referred to as adolescents and young adults (AYA), are an underserved population who often experience unfavorable cancer outcomes. Cancer is a leading cause of death in this population and AYA patients remain especially vulnerable, given their predisposition to certain cancer types, distinct cancer biology, and unique physical and mental health needs during survivorship (see Survivorship Disparities in Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Patients). Recent studies that evaluated the barriers to enrollment of AYA patients identified limited research staff and resources, lack of awareness of available trials among health care staff, and lack of communication between pediatric and medical oncologists as frequent reasons for not enrolling in cancer clinical trials (520)Nupur Mittal A-ML, Wade Kyono, David S. Dickens, Allison Grimes, John M. Salsman, Brad H. Pollock, and Michael Roth. Barriers to Pediatric Oncologist Enrollment of Adolescents and Young Adults on a Cross-Network National Clinical Trials Network Supportive Care Cancer Clinical Trial. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 2022;11:117-21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](521)Mittal N, Saha A, Avutu V, Monga V, Freyer DR, Roth M. Shared Barriers and Facilitators to Enrollment of Adolescents and Young Adults on Cancer Clinical Trials. Scientific reports 2022;12:3875. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Implicit biases among heath care staff who are responsible for recruiting patients on clinical trials can contribute to exclusion of minority groups. In a recent study, researchers interviewed 91 individuals (from research staff to cancer center leaders) across five major U.S. cancer centers (522)Niranjan SJ, Martin MY, Fouad MN, Vickers SM, Wenzel JA, Cook ED, et al. Bias and Stereotyping among Research and Clinical Professionals: Perspectives on Minority Recruitment for Oncology Clinical Trials. Cancer 2020;126:1958-68. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Prominent themes from these interviews included perceptions that minority participants are less knowledgeable about clinical trials and therefore more difficult to communicate with; that minorities wouldn’t follow trial protocols; and that race should not be a consideration when recruiting for trials. A framework for addressing such biases is urgently needed, including diversification of the cancer research and care workforce.

Beyond individual-level factors, there are barriers that operate at the level of the health care system, as well as the community and/or society. Many of these barriers are driven by structural inequities and social injustices and negatively impact SDOH (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities). Some of the major system-level and structural barriers include lack of trial availability; complexity of clinical trials; time constraints for proper informed consent and clinical trial paperwork; patient exclusion due to narrow eligibility criteria; medical distrust; and lack of facilitators, such as translators or patient navigators and community engagement in low-resource settings (512)Kahn JM, Gray DM, 2nd, Oliveri JM, Washington CM, DeGraffinreid CR, Paskett ED. Strategies to Improve Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Clinical Trials. Cancer 2022;128:216-21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](523)Garrick O, Mesa R, Ferris A, Kim ES, Mitchell E, Brawley OW, et al. Advancing Inclusive Research: Establishing Collaborative Strategies to Improve Diversity in Clinical Trials. Ethn Dis 2022;32:61-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Lack of trial availability in areas with a high proportion of racial and ethnic minorities can significantly limit their enrollment in clinical research. While Black men have a disproportionately higher incidence and mortality from prostate cancer, a recent study showed that U.S. counties with a higher proportion of Black residents were 15 percent less likely to have cancer care facilities (524)Wang W-J, Ramsey SD, Bennette CS, Bansal A. Racial Disparities in Access to Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials: A County-Level Analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 2021;6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, among counties with cancer care facilities, those with a higher proportion of Black residents had significantly fewer prostate cancer trials available. It should be noted that many clinical trials enroll participants from outside the United States. According to a new study, underrepresentation of Black patients in cancer clinical trials may be exacerbated with increasing globalization of clinical research (525)Tharakan S, Zhong X, Galsky MD. The Impact of the Globalization of Cancer Clinical Trials on the Enrollment of Black Patients. Cancer 2021;127:2294-301. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. When clinical trials are conducted in other countries, Black patients are enrolled at less than half the rate of U.S. studies. Between 2015 and 2018, 64 percent of patients in 21 clinical trials that led to FDA approvals of 18 anticancer drugs were enrolled outside the U.S., and Black patients accounted for only three percent of participants. As a result, researchers are concerned about the effectiveness of these therapeutics in Black patients. These data highlight the importance of adequate availability of enrollment sites in locations with a higher proportion of racial and ethnic minority residents.

Achieving Equity in Clinical Cancer Research

Overcoming barriers to clinical trial participation for all segments of the population will require all stakeholders in the cancer research and care community to actively come together and develop multifaceted approaches that include the implementation of new, more effective education and policy initiatives. Intervention strategies need to address barriers across all levels from dismantling structural racism to catering to the individual needs of cancer patients. Ongoing research from academia, biopharmaceutical industry, and federal organizations has identified many approaches that can facilitate enrollment of participants from diverse sociodemographic backgrounds (512)Kahn JM, Gray DM, 2nd, Oliveri JM, Washington CM, DeGraffinreid CR, Paskett ED. Strategies to Improve Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Clinical Trials. Cancer 2022;128:216-21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](526)Owens-Walton J, Williams C, Rompré-Brodeur A, Pinto PA, Ball MW. Minority Enrollment in Phase II and III Clinical Trials in Urologic Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2022;40(14):1583-1589. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](527)U.S. Food & Drug. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations—Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry. [updated November 13, 2020, cited 2022 April 22].(528)Fashoyin-Aje L, Beaver JA, Pazdur R. Promoting Inclusion of Members of Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups in Cancer Drug Development. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1445-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The goals of these strategies are to improve access to clinical trials for diverse populations in the community, increase patient awareness and understanding of clinical research, build trust in communities, improve support of clinical trial sites and their health care staff, and report race/ethnicity-related information while publishing clinical trial data.

Community Engagement and Patient Navigation

Research has shown that community outreach and patient navigation can enhance minority participation in clinical trials. As one example, a culturally tailored educational intervention that used trained community health educators to deliver presentations at town halls held at local churches, community health clinics, and other community centers, was able to increase knowledge about clinical trials, trust in medical researchers, and intent for clinical trial participation among Black and Hispanic participants (529)Cunningham-Erves J, Mayo-Gamble TL, Hull PC, Lu T, Barajas C, McAfee CR, et al. A Pilot Study of a Culturally-Appropriate, Educational Intervention to Increase Participation in Cancer Clinical Trials among African Americans and Latinos. Cancer Causes Control 2021;32:953-63. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Connecting with the community and building trust are particularly important when engaging with racial and ethnic minorities who may distrust research and the health care system due to historical injustices. For instance, researchers have indicated that community based participatory research utilizing tribal and academic collaboration is a promising approach when collecting genetic data from AI/AN populations (530)Carroll DM, Hernandez C, Braaten G, Meier E, Jacobson P, Begnaud A, et al. Recommendations to Researchers for Aiding in Increasing American Indian Representation in Genetic Research and Personalized Medicine. Per Med 2021;18:67-74. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Specifically, the investigators recommended becoming familiar with tribal governance and its structure, building trust with the AI/AN community, being clear about expectations and ideal communication strategies, developing a research agreement and plan for using and sharing genetic data with participants, and ensuring appropriate review by the tribe for ethical and cultural considerations. In another study, a focus group conducted at a safety-net hospital identified fear of clinical trials as a major barrier to clinical trial participation for Black patients and recommended patient navigation to provide social, emotional, and logistical support as a potential facilitating factor (513)Hernandez ND, Durant R, Lisovicz N, Nweke C, Belizaire C, Cooper D, et al. African American Cancer Survivors’ Perspectives on Cancer Clinical Trial Participation in a Safety-Net Hospital: Considering the Role of the Social Determinants of Health. J Cancer Educ 2021;10.1007/s13187-021-01994-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Trust-based interventions that promote relationships between investigators, minority-serving physicians, and their minority patients have been shown to increase minority recruitment to clinical trials (531)Tilley BC, Mainous AG, 3rd, Amorrortu RP, McKee MD, Smith DW, Li R, et al. Using Increased Trust in Medical Researchers to Increase Minority Recruitment: The Recruit Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2021;109:106519. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The vital role of community engagement and patient navigation was highlighted in a recent study that evaluated the impact of a multifaceted intervention on enrollment of Black patients in clinical trials (532)Guerra CE, Sallee V, Hwang W-T, Bryant B, Washington AL, Takvorian SU, et al. Accrual of Black Participants to Cancer Clinical Trials Following a Five-Year Prospective Initiative of Community Outreach and Engagement. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:100. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The intervention included culturally tailored marketing, partnerships with faith-based organizations serving Black communities to conduct educational events, collaboration with Lyft and Ride Health to address transportation barriers, and patient education by nurse navigators regarding cancer clinical trials (532)Guerra CE, Sallee V, Hwang W-T, Bryant B, Washington AL, Takvorian SU, et al. Accrual of Black Participants to Cancer Clinical Trials Following a Five-Year Prospective Initiative of Community Outreach and Engagement. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:100. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While Black residents comprise 19 percent of the population and 17 percent of cancer cases in the study’s catchment area, only 11 percent of patients were Black prior to the intervention. Furthermore, only 12 percent and eight percent of Black participants accrued onto treatment and nontherapeutic interventional clinical trials, respectively. After implementation of the community outreach and engagement intervention these numbers increased to 24 percent and 33 percent respectively. The initiative utilized community venues including churches, neighborhoods, parks, and health centers with formats ranging from educational forums to wellness fairs and reached over 10,000 individuals.

Addressing the System-Level and Structural Barriers

While certain system-level barriers to clinical trial participation may be more difficult to tackle, some could be addressed in the short term. One immediate approach could be to conduct clinical trials at facilities that treat a high percentage of racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved patients. Currently, many late-phase clinical trials are conducted outside the United States, and those within the United States are often limited to the high-volume cancer centers where minority patients are underrepresented (533)Kanapuru B, Singh H, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Myers A, Kim G, Farrell A, et al. FDA Analysis of Patient Enrollment by Region in Clinical Trials for Approved Oncological Indications. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2539. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, nearly 85 percent of cancer patients are treated in community centers, compared with only about 15 percent in larger, academic centers (534)Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, Minasian LM, Fleury ME. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Magnitude of Structural, Clinical, and Physician and Patient Barriers to Cancer Clinical Trial Participation. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2019;111:245-55. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is, therefore, crucial that these studies be available to Minority-Serving Institutions including at safety-net hospitals, which often operate in inner-city communities and provide a larger share of care to low-income and uninsured populations. Additionally, the clinical trial infrastructures must be set up to address social needs and alleviate common barriers such as food and housing insecurity, out-of-pocket costs, time off work, child and elder care, etc. To encourage cancer patients to participate in clinical studies, research teams need to reach out and to work with minority patient populations. As one example, the NCI’s Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) is successfully bringing cancer clinical trials into diverse community settings.

Another key strategy to diversify clinical trial participants is to simplify and expand eligibility criteria that often lead to exclusion of racial and ethnic minority patients. These criteria need to keep up with scientific innovation, be pragmatic, and allow flexibility for patients with medical or physical limitations other than their cancer. If candidate anticancer therapeutics are to be given to a broad range of patients once approved, they should be tested in a broad range of patients including those who may have coexisting medical conditions. Furthermore, clinical trials should include collection of real-world data and evidence in the form of patient-reported outcomes, to help us better understand the patient experience from diverse populations.

Data from recent studies indicate that cutting edge technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) platforms can play a critical role in these efforts. A new report, which used an AI platform to harness data from electronic health records from more than 60,000 lung cancer patients and publicly available trial eligibility criteria from clinicaltrials.gov to evaluate the real-world impact of eligibility criteria on patient recruitment and outcomes, found that many patients who were excluded from certain trials due to restrictive criteria could have benefited from treatments provided in the trials (535)Liu R, Rizzo S, Whipple S, Pal N, Pineda AL, Lu M, et al. Evaluating Eligibility Criteria of Oncology Trials Using Real-World Data and Ai. Nature 2021;592:629-33. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In fact, when the researchers broadened the eligibility criteria using the AI-guided approach, the estimated number of eligible patients more than doubled. In addition, the study also concluded that trials with broader eligibility may not have any more adverse event-related treatment withdrawals compared to trials with strict eligibility criteria. These data highlight the need for innovation in the future design of more inclusive clinical trials while still maintaining patient safety.

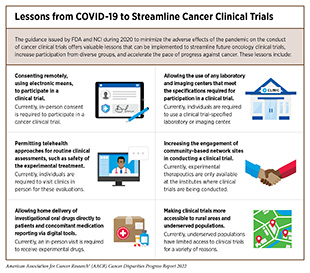

FDA has prioritized improving representation of racial, ethnic, and gender minority populations in oncology clinical trials (see Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers for Patients). The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) at FDA released a guidance in November 2020 to encourage clinical trial sponsors to implement strategies that would increase representation of racial and ethnic minorities (527)U.S. Food & Drug. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations—Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry. [updated November 13, 2020, cited 2022 April 22].. Among the recommendations included in the guidance are broadening eligibility criteria for late-stage efficacy trials when more patients with comorbidities can be safely included; encouraging trials or follow-up studies to include representation of racial and ethnic minorities, when possible, to definitively determine differences in safety and efficacy; conducting trials at decentralized local health facilities while maintaining data integrity and patient safety; and advancing the appropriate use of real-world evidence to fill evidence gaps where randomized clinical trials may not be feasible. It must be noted that the COVID-19 pandemic, despite its adverse effects on nearly all aspects of cancer science and medicine, also offered a blueprint of success to further revise and reform the clinical trial enterprise and the drug approval process (see the sidebar on Lessons from COVID-19 to Streamline Cancer Clinical Trials). Guidance issued by FDA and NCI during 2020 to minimize the adverse effects of the pandemic on the conduct of cancer clinical trials offers valuable lessons that can be implemented to streamline future oncology clinical trials, increase participation from racial and ethnic minorities and other historically underrepresented populations by eliminating system-level and structural barriers, and accelerate the pace of progress against cancer.

Disparities in Cancer Treatment

The dedicated efforts of individuals working throughout the medical research cycle are constantly powering the translation of new research discoveries into advances in cancer treatment that are improving survival and quality of life for patients in the United States like Faye Belvin and Ray Spells and around the world. Much of the most recent progress was highlighted in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2021, which documented many new cancer treatments approved by FDA in the 12 months covered in this eleventh edition of the annual report (2)American Association for Cancer Research. Aacr Cancer Progress Report. [updated October 13, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Despite these advances, racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations continue to experience more frequent and higher severity of multilevel barriers to quality cancer treatment including treatment delays, lack of access to guideline-concordant treatment, and higher rates of treatment-related financial toxicities. The same population groups may also experience overt discrimination and/or implicit bias during the delivery of care (536)Torres TK, Chase DM, Salani R, Hamann HA, Stone J. Implicit Biases in Healthcare: Implications and Future Directions for Gynecologic Oncology. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2022; S0002-9378(22)00005-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](537)Berrahou IK, Snow A, Swanson M, Obedin-Maliver J. Representation of Sexual and Gender Minority People in Patient Nondiscrimination Policies of Cancer Centers in the United States. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2022;20:253-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Most of the disparities in cancer care can be attributed to adverse differences in SDOH (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities). According to a recent survey of 165 cancer physicians practicing in community- or hospital-based settings, 93 percent of respondents agreed that SDOH negatively impacted their patients’ outcomes (538)Zettler ME, Feinberg BA, Jeune-Smith Y, Gajra A. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Cancer Care: A Survey of Community Oncologists. BMJ Open 2021;11:e049259. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Financial insecurity, lack of health insurance, and access to transportation were identified as the greatest obstacles in accessing quality health care services. These obstacles can be compounded for those living in remote or rural areas with limited access to health care facilities, as well as for patients who lack health literacy and have language barriers (see sidebar on Multilevel Barriers to Quality Cancer Treatment). Notably, while evidence suggests that receiving health care from a provider who is of the same race and/or ethnicity, or speaks the same language as the patient can improve patient satisfaction and quality of care (539)Seible DM, Kundu S, Azuara A, Cherry DR, Arias S, Nalawade VV, et al. The Influence of Patient-Provider Language Concordance in Cancer Care: Results of the Hispanic Outcomes by Language Approach (HOLA) Randomized Trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;111:856-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], fewer Black adults (22 percent) report having providers who are of the same race compared to White adults (74 percent) (527)U.S. Food & Drug. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations—Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry. [updated November 13, 2020, cited 2022 April 22].. Among Hispanic/Latino adults, only 23 percent report having the same race and/or ethnicity or language preference as their provider. Fear of discrimination and cultural incompetency are major barriers for patients from SGM populations and often leads to avoidance of care and nondisclosure of sexual orientation and gender identity (540)Russell S, Corbitt N. Addressing Cultural Competency: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Cancer Care. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2022;26:183-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Therefore, it is encouraging that a recent survey that assessed patient services, support, patient and community engagement, and policies at leading health care facilities across the United States, reported significant improvement in the adoption of SGM-inclusive policies and practices (541)Human Rights Campaign Foundation. Healthcare Equality Index 2022. [updated March 2022, cited 2022 April 22]..

The multilevel barriers result in racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations experiencing greater incidence, mortality, and morbidity from several types of cancers due to delayed diagnosis, a more advanced stage of disease at diagnosis, more rapid progression to aggressive disease, increased rates of development of treatment resistance, higher cancer-specific and cancer-related mortality rates, and worse survival. It should be noted that patients with intersectional identities often experience multilevel barriers to cancer care that adversely impact screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. As one example, recent data have shown that Black and AI/AN populations living in rural areas experience greater poverty and lack of access to quality care, which expose them to greater risk of experiencing poorer cancer outcomes (551)Zahnd WE, Murphy C, Knoll M, Benavidez GA, Day KR, Ranganathan R, et al. The Intersection of Rural Residence and Minority Race/Ethnicity in Cancer Disparities in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021;18:1384. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is a critical need for additional research to understand the intersections of geography, race/ethnicity, socioeconomics, sexual orientation, and gender identity on disparities in cancer treatment and mitigate these disparities through reduced structural barriers and interpersonal biases in cancer care, increased access, and implementation of evidence-based interventions.

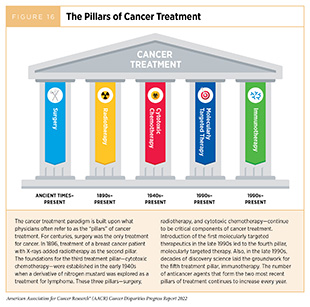

In the following sections, we discuss major disparities among racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations in the use of the main pillars of cancer treatment (Figure 16) and highlight areas where advances have been made in achieving equity in cancer treatment. Importantly, several recent studies have pointed out that disparities in the receipt of care as well as outcomes for many cancers can be eliminated if every patient has equivalent access to quality health care services (553)Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, Vitzthum LK, Deka R, Sarkar RR, et al. Survival of African American and Non-Hispanic White Men with Prostate Cancer in an Equal-Access Health Care System. Cancer 2020;126:1683-90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](554)Fillmore NR, Yellapragada SV, Ifeorah C, Mehta A, Cirstea D, White PS, et al. With Equal Access, African American Patients Have Superior Survival Compared to White Patients with Multiple Myeloma: A Va Study. Blood 2019;133:2615-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](555)Cykert S, Eng E, Walker P, Manning MA, Robertson LB, Arya R, et al. A System-Based Intervention to Reduce Black-White Disparities in the Treatment of Early Stage Lung Cancer: A Pragmatic Trial at Five Cancer Centers. Cancer Medicine 2019;8:1095-102. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](556)Chu QD, Hsieh MC, Gibbs JF, Wu XC. Treatment at a High-Volume Academic Research Program Mitigates Racial Disparities in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol 2021;12:2579-90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](557)Kotha NV, Kumar A, Qiao EM, Qian AS, Voora RS, Nalawade V, et al. Association of Health-Care System and Survival in African American and Non-Hispanic White Patients with Bladder Cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2022;114(4):600-608. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Treatment with Surgery, Radiotherapy, and Chemotherapy

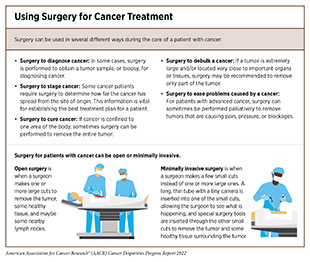

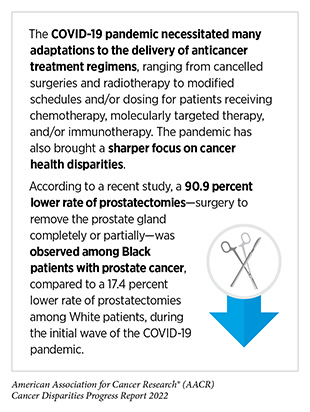

For many decades, surgery was the only pillar (Figure 16) of cancer treatment and remains an important treatment option for many patients (see sidebar on Using Surgery for Cancer Treatment). Surgery is the foundation of treatment for many cancer types for which there are significant disparities in mortality and morbidity experienced by racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations. For cancers associated with high mortality, such as lung and pancreatic cancers, surgical resection is key to survival when these tumors are detected at an early stage. For cancers with better prognosis, specialty surgeries are necessary to optimize quality of life after the treatment, such as reconstruction surgery for certain breast cancer patients requiring mastectomy and sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer patients. Researchers are continuously innovating new and improved strategies to maximize the benefit and minimize harms from surgery for cancer patients. Thanks to such efforts, overall mortality rates after surgery for many common types of cancer have declined over the past decade (558)Lam MB, Raphael K, Mehtsun WT, Phelan J, Orav EJ, Jha AK, et al. Changes in Racial Disparities in Mortality after Cancer Surgery in the US, 2007-2016. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2027415. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Post surgery mortality rates have improved for both White and Black patients. However, the mortality gap between Black and White patients, overall, or for individual cancer surgery procedures, has not narrowed (558)Lam MB, Raphael K, Mehtsun WT, Phelan J, Orav EJ, Jha AK, et al. Changes in Racial Disparities in Mortality after Cancer Surgery in the US, 2007-2016. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2027415. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

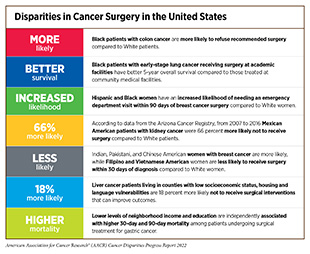

Racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations often experience disparities in surgical management of cancer including treatment delays or refusals and lack of guideline-concordant care (see sidebar on Disparities in Cancer Surgery in the United States). These disparities are seen across many cancer types including the most diagnosed cancers in the U.S. and may contribute to worse outcomes (559)Namburi N, Timsina L, Ninad N, Ceppa D, Birdas T. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Management of Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am J Surg 2021;S0002-9610(21)00614-0. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](560)Obeng-Gyasi S, Asad S, Fisher JL, Rahurkar S, Stover DG. Socioeconomic and Surgical Disparities Are Associated with Rapid Relapse in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:6500-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](561)Cho B, Han Y, Lian M, Colditz GA, Weber JD, Ma C, et al. Evaluation of Racial/Ethnic Differences in Treatment and Mortality among Women with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1016-23. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As one example, Black women with nonmetastatic TNBC have a 28 percent higher risk of breast cancer mortality compared to White women, partly attributable to their disparities in the receipt of surgery and chemotherapy (561)Cho B, Han Y, Lian M, Colditz GA, Weber JD, Ma C, et al. Evaluation of Racial/Ethnic Differences in Treatment and Mortality among Women with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1016-23. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The most prominent barriers to cancer surgery include adverse SDOH such as lack of health insurance, lack of social support, and poverty, among other factors (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities). According to a recent report, Black patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are almost twice as likely to delay surgery compared to White patients and 26 percent of the racial disparity can be attributed to SDOH (569)Neroda P, Hsieh MC, Wu XC, Cartmell KB, Mayo R, Wu J, et al. Racial Disparity and Social Determinants in Receiving Timely Surgery among Stage I-Iiia Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients in a U.S. Southern State. Front Public Health 2021;9:662876. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. NSCLC patients experiencing adverse SDOH are also likely to have worse long-term survival (559)Namburi N, Timsina L, Ninad N, Ceppa D, Birdas T. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Management of Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am J Surg 2021;S0002-9610(21)00614-0. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent study showed that Black and Hispanic liver cancer patients residing in counties with a high level of social vulnerability (a composite measure for SDOH) were significantly more likely not to have received surgical intervention for their cancer compared to those living in less vulnerable counties (567)Azap RA, Hyer JM, Diaz A, Paredes AZ, Pawlik TM. Association of County-Level Vulnerability, Patient-Level Race/Ethnicity, and Receipt of Surgery for Early-Stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JAMA Surgery 2021;156:197-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Racial and ethnic minority patients are less likely to travel long distances to seek surgical treatment and are more likely to receive their cancer care in safety-net and public hospitals, which often lack multidisciplinary programs that can support complex cancer perioperative needs compared with academic hospitals or specialty cancer centers (570)Kirkpatrick DR, Markov NP, Fox JP, Tuttle RM. Initial Surgical Treatment for Breast Cancer and the Distance Traveled for Care. Am Surg 2021;87:1280-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](571)Sarkar RR, Courtney PT, Bachand K, Sheridan PE, Riviere PJ, Guss ZD, et al. Quality of Care at Safety-Net Hospitals and the Impact on Pay-for-Performance Reimbursement. Cancer 2020;126:4584-92. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]

. In this regard, it should be noted that even at safety-net settings, multidisciplinary cancer care and appropriate initiation of treatment can lead to equitable outcomes (572)Kelly KN, Hernandez A, Yadegarynia S, Ryon E, Franceschi D, Avisar E, et al. Overcoming Disparities: Multidisciplinary Breast Cancer Care at a Public Safety Net Hospital. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021;187:197-206. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Implicit biases among health care providers may also contribute to disparities in cancer surgery. As one example, Black women with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy surgery were less likely to be referred for breast reconstruction compared to White patients. Additionally, even when referred to a plastic surgeon, Black patients were less likely to be offered reconstruction (573)Tseng JF, Kronowitz SJ, Sun CC, Perry AC, Hunt KK, Babiera GV, et al. The Effect of Ethnicity on Immediate Reconstruction Rates after Mastectomy for Breast Cancer. Cancer 2004;101:1514-23. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Lack of or limited access to surgical facilities is a major barrier in seeking cancer surgery. It is known that a greater distance to a surgical facility is associated with a decreased likelihood of treatment (574)Tang C, Lei X, Smith GL, Pan HY, Hoffman KE, Kumar R, et al. Influence of Geography on Prostate Cancer Treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;109:1286-95. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Patients from the rural U.S. are particularly vulnerable. Recent data show that density of surgical specialists is considerably lower in rural areas compared to urban areas and the rural-urban gap has been exacerbated between 2004 and 2017 with the largest increase in disparity being among colorectal surgeons (575)Herb J, Holmes M, Stitzenberg K. Trends in Rural-Urban Disparities among Surgical Specialties Treating Cancer, 20042017. J Rural Health 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The remote location of many AI/AN reservations is a contributing factor to the surgical disparities among these populations. In a recent study, researchers found that, compared to White women, AI/AN women with early-stage breast cancer had higher rates of mastectomies (41 percent versus 34 percent) and lower rates of lumpectomies (59 percent versus 66 percent) (576)Erdrich J, Cordova-Marks F, Monetathchi AR, Wu M, White A, Melkonian S. Disparities in Breast-Conserving Therapy for Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native Women Compared with Non-Hispanic White Women. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2022;29:1019-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], albeit with significant regional variations. These data are concerning because lumpectomy followed by radiation can decrease complications and pain post surgery with similar survival compared to mastectomy. Lack of knowledge of available treatment options as well as distance and transportation to medical centers can contribute to these disparities. Higher use of mastectomy in certain vulnerable populations may also stem from mistrust of the health care system since mastectomy is more definitive and may reduce the need for follow-up encounters with the health care system.

Taken together these data highlight the need for multilevel interventions to ensure equitable delivery of guideline-recommended surgery for all cancer patients. All stakeholders must work together to improve effective communication and access to health care resources for patients while continuing further research into the mechanisms that perpetuate disparities. The vital importance of access to surgical treatment is highlighted by studies showing that disparities in survival between Black and White patients are eliminated in health care setting where all patients receive guideline-concordant treatment (579)Hoehn RS, Rieser CJ, Winters S, Stitt L, Hogg ME, Bartlett DL, et al. A Pancreatic Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic Eliminates Socioeconomic Disparities in Treatment and Improves Survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:2438-46. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](580)Zhao S, Xian X, Tian P, Li W, Wang K, Li Y. Efficacy of Combination Chemo-Immunotherapy as a First-Line Treatment for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients with HER2 Alterations: A Case Series. Frontiers in Oncology 2021;11:633522. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, concerted efforts from all stakeholders are needed to diversify the current surgical oncology workforce which significantly lacks representation from minorities and women (581)Morrow M, Newman LA. Disparities in Cancer Care: Educational Initiatives. Ann Surg Oncol 2022;29:2136-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Radiotherapy uses high energy rays or particles to control the growth of and/or eradicate cancer cells. Discovery of X-rays in 1895 allowed visualization of internal organs at low doses. A year later, the effective use of X-rays at high doses to treat a breast cancer patient firmly established radiotherapy as the second pillar of cancer treatment. Today, about 50 percent of all cancer patients in the United States receive radiotherapy as part of their treatment regimens. There are many types and uses of radiotherapy (see sidebar on Using Radiation in Cancer Treatment). It is important to note that radiotherapy may also have adverse side effects, partly because of the radiation-induced damage to healthy organs surrounding the tumor tissue. Researchers are continuously refining the use of radiotherapy to make it safer and more effective while designing novel radiotherapeutics (to be used alone or in combination with other types of treatments) to target more cancer types.

Unfortunately, reduced access to and utilization of radiation therapy have been well documented among U.S. racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations and contribute to cancer health disparities. A recent analysis, which examined the receipt of more than 250,000 treatments using Medicare claims and beneficiary data between 2016 and 2018, found that failure to initiate radiation treatment was 29 percent greater for Black, Hispanic, and AI/AN patients compared to White patients (582)Mantz CA, Thaker NG, Deville C, Jr., Hubbard A, Pendyala P, Mohideen N, et al. A Medicare Claims Analysis of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Access to Radiation Therapy Services. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2022; 10.1007/s40615-022-01239-0. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Even when radiation treatment was initiated, Black and Hispanic patients required significantly more days for completion of the treatment compared to White patients. Additionally, studies have shown that interruptions to radiation treatment disproportionately affect financially and socially vulnerable patients and can be mapped to disadvantaged neighborhoods such as urban, majority Black, low-income neighborhoods as well as rural, majority White, low-income regions (583)Wakefield DV, Carnell M, Dove APH, Edmonston DY, Garner WB, Hubler A, et al. Location as Destiny: Identifying Geospatial Disparities in Radiation Treatment Interruption by Neighborhood, Race, and Insurance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;107:815-26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Disparities in the utilization of radiation therapy are evident across cancer types. Lack or underutilization of the treatment among the disadvantaged population groups is also evident for state-of-the-art treatment regimens such as stereotactic body radiotherapy, hypofractionated radiotherapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy, all of which have been shown to improve outcomes for patients while reducing the adverse side effects of radiation (574)Tang C, Lei X, Smith GL, Pan HY, Hoffman KE, Kumar R, et al. Influence of Geography on Prostate Cancer Treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;109:1286-95. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](584)Woodward SG, Varshney K, Anne PR, George BJ, Willis AI. Trends in Use of Hypofractionated Whole Breast Radiation in Breast Cancer: An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;109:449-57. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](585)Laucis AM, Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Dominello MM, Walker EM, Abu-Isa EI, et al. The Role of Facility Variation on Racial Disparities in Use of Hypofractionated Whole Breast Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;107:949-58. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As one example, a recent advance is the emergence of hypofractionated radiotherapy, whereby patients receive fewer but higher doses of radiotherapy compared with the traditional course and complete treatment over a shorter period. In 2018, new guidelines were introduced which recommended expanding the use of hypofractionated radiotherapy for treating breast cancer (586)Smith BD, Bellon JR, Blitzblau R, Freedman G, Haffty B, Hahn C, et al. Radiation Therapy for the Whole Breast: Executive Summary of an American Society for Radiation Oncology (Astro) Evidence-Based Guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol 2018;8:145-52. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This change was spurred by research showing that hypofractionated radiotherapy is as effective as the traditional course of radiotherapy and has fewer adverse effects (587)Haviland JS, Owen JR, Dewar JA, Agrawal RK, Barrett J, Barrett-Lee PJ, et al. The Uk Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (Start) Trials of Radiotherapy Hypofractionation for Treatment of Early Breast Cancer: 10-Year Follow-up Results of Two Randomised Controlled Trials. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1086-94. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](588)Shaitelman SF, Schlembach PJ, Arzu I, Ballo M, Bloom ES, Buchholz D, et al. Acute and Short-Term Toxic Effects of Conventionally Fractionated Vs Hypofractionated Whole-Breast Irradiation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2015;1:931-41. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While use of hypofractionated radiotherapy has increased in recent years, the likelihood of receiving treatment is greater among patients with higher median income, those with private insurance, and those being treated at an academic center (584)Woodward SG, Varshney K, Anne PR, George BJ, Willis AI. Trends in Use of Hypofractionated Whole Breast Radiation in Breast Cancer: An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;109:449-57. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, a recent analysis indicated that after undergoing breast-conserving surgery, Black and Asian patients receive hypofractionated radiation therapy less often than White patients, and these disparities are driven by variations in treatment facility-specific hypofractionation use (585)Laucis AM, Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Dominello MM, Walker EM, Abu-Isa EI, et al. The Role of Facility Variation on Racial Disparities in Use of Hypofractionated Whole Breast Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;107:949-58. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Adverse differences in SDOH as well as clinical factors are associated with disparities in timely radiation treatment. Research has shown that lack of or inadequate health insurance, low socioeconomic status, limited access to care facilities, and having additional comorbidities, are among the prominent drivers of inequities in the utilization of radiation treatment (585)Laucis AM, Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Dominello MM, Walker EM, Abu-Isa EI, et al. The Role of Facility Variation on Racial Disparities in Use of Hypofractionated Whole Breast Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;107:949-58. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](589)Noyes EA, Burks CA, Larson AR, Deschler DG. An Equity-Based Narrative Review of Barriers to Timely Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol 2021;6:1358-66. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](590)Boyce-Fappiano D, Nguyen KA, Gjyshi O, Manzar G, Abana CO, Klopp AH, et al. Socioeconomic and Racial Determinants of Brachytherapy Utilization for Cervical Cancer: Concerns for Widening Disparities. JCO Oncol Pract 2021;17:e1958-e67. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Disparities in access to radiation therapy facilities have been identified as a major barrier to receiving treatment for racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations. For instance, research has identified significant disparities in access to radiation therapy facilities in Washington State specifically for AI/AN and rural residents (591)Greer MD, Amiri S, Denney JT, Amram O, Halasz LM, Buchwald D. Disparities in Access to Radiation Therapy Facilities among American Indians/Alaska Natives and Hispanics in Washington State. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2022;112:285-93. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, regions with greater geographic access to radiation therapy tend to be of higher socioeconomic status and better insured (592)Maroongroge S, Wallington DG, Taylor PA, Zhu D, Guadagnolo BA, Smith BD, et al. Geographic Access to Radiation Therapy Facilities in the United States. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2022;112:600-10. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] and increasing distance from treatment facility is known to be associated with lower receipt of radiation treatment (593)Arega MA, Yang DD, Royce TJ, Mahal BA, Dee EC, Butler SS, et al. Association between Travel Distance and Use of Postoperative Radiation Therapy among Men with Organ-Confined Prostate Cancer: Does Geography Influence Treatment Decisions? Practical Radiation Oncology 2021;11:e426-e33. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Rural residents are at a particularly higher risk of living farther away from radiation facilities, specifically those offering emerging treatment options such as stereotactic body radiotherapy or particle therapy (see sidebar on Using Radiation in Cancer Treatment) (574)Tang C, Lei X, Smith GL, Pan HY, Hoffman KE, Kumar R, et al. Influence of Geography on Prostate Cancer Treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2021;109:1286-95. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Overall, these findings call for new evidence-based strategies to improve access to radiotherapy services for cancer patients from all medically underserved populations. When developing such interventions, health care providers must consider not only clinical factors but also the adverse influences of SDOH. For maximal benefits in cancer outcomes there must be structural changes in public health and health care delivery to promote equitable access to care for all. Encouragingly, it has been shown in many settings that equitable use of standard of care radiotherapy can overcome the racial and ethnic disparities seen in cancer outcomes (590)Boyce-Fappiano D, Nguyen KA, Gjyshi O, Manzar G, Abana CO, Klopp AH, et al. Socioeconomic and Racial Determinants of Brachytherapy Utilization for Cervical Cancer: Concerns for Widening Disparities. JCO Oncol Pract 2021;17:e1958-e67. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Chemotherapy remains the backbone of cancer treatment for many patients. First introduced as a pillar of cancer treatment in the early to mid-20th century, use of chemotherapy is continually evolving to minimize its potential harms to cancer patients, while maximizing its benefits.

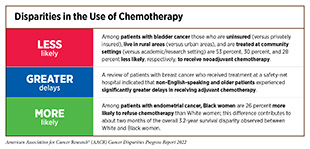

Unfortunately, many reports have documented that patients with cancer from racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations are less likely to receive recommended chemotherapy (see sidebar on the Disparities in the Use of Chemotherapy). These disparities arise due to a range of issues from socioeconomic disadvantages including poverty, lack of health insurance, being treated at community hospital setting, and language barriers to clinical factors such as advanced age. Results from recent studies suggest that even among those with private health insurance, Black and Hispanic patients are still less likely to receive chemotherapy, highlighting the need for additional research to identify factors beyond health insurance that are preventing underserved patients from receiving the standard of care for their cancers (594)Mitsakos AT, Irish W, Parikh AA, Snyder RA. The Association of Health Insurance and Race with Treatment and Survival in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. PLoS One 2022;17:e0263818. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is also evidence suggesting clinical differences in the response to chemotherapy for patients from different racial and ethnic backgrounds, with minority patients benefiting less from the chemotherapy exposure (595)Hoeh B, Würnschimmel C, Flammia RS, Horlemann B, Sorce G, Chierigo F, et al. Effect of Chemotherapy in Metastatic Prostate Cancer According to Race/Ethnicity Groups. Prostate 2022;82:676-86. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These data underscore the importance of diversifying accrual in cancer clinical trials to ensure the safety and efficacy of therapeutics for patients from all sociodemographic backgrounds.

Treatment with chemotherapeutics can have adverse effects on patients. These effects can arise during treatment and continue in the long term, or they can appear months or even years later. As a result, researchers are investigating ways to identify patients who may benefit most from these treatments (599)Spring LM, Fell G, Arfe A, Sharma C, Greenup R, Reynolds KL, et al. Pathologic Complete Response after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Impact on Breast Cancer Recurrence and Survival: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Clinical Cancer Research 2020;26:2838-48. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers use a test known as the Oncotype DX score to measure how aggressive a woman’s breast cancer is and to decide whether she needs chemotherapy after surgery (600)Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, Pritchard KI, Albain KS, Hayes DF, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Guided by a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2018;379:111-21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The test works by looking at the activity of 21 genes within the tumor and calculating a score between 0 and 100. Oncotype DX scores fall into three categories that reflect the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Scores under 10 indicate a low risk, between 11 and 25 are intermediate risk, while 26 and above are considered high risk. Most patients with low and intermediate risk scores get hormone therapy after surgery, whereas those with high scores get chemotherapy in addition to hormone therapy. Recent data suggest that, in addition to recurrence scores, menopausal status of the patient should be taken into consideration while making decisions on chemotherapy (601)Kalinsky K, Barlow WE, Gralow JR, Meric-Bernstam F, Albain KS, Hayes DF, et al. 21-Gene Assay to Inform Chemotherapy Benefit in Node-Positive Breast Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2021;385:2336-47. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Oncotype DX testing followed by guideline-concordant treatment is associated with improved outcomes. Unfortunately, among breast cancer patients who are recommended chemotherapy following a high Oncotype DX score, many refuse treatment and the rates of refusal are higher among women who are Black, older, and lack private health insurance (602)Bilani N, Ladki S, Yaghi M, Main O, Jabbal IS, Elson L, et al. Factors Associated with the Decision to Decline Chemotherapy in Patients with Early-Stage, ER+/HER2- Breast Cancer and High-Risk Scoring on Genomic Assays. Clinical Breast Cancer 2022;(4):367-373. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

While there are some variations in the published data, some recent studies have indicated that the Oncotype DX test may be less accurate at predicting the risk of breast cancer death for Black women compared to White women (603)Hoskins KF, Danciu OC, Ko NY, Calip GS. Association of Race/Ethnicity and the 21-Gene Recurrence Score with Breast Cancer– Specific Mortality among US Women. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:370-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](604)Collin LJ, Yan M, Jiang R, Ward KC, Crawford B, Torres MA, et al. Oncotype Dx Recurrence Score Implications for Disparities in Chemotherapy and Breast Cancer Mortality in Georgia. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019;5:32. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Specifically, the researchers found that overall, Black women had higher Oncotype DX scores than White women and even among women with similar scores, Black patients were more likely to die of breast cancer compared to White women. These data highlight the importance of additional research into the cellular and molecular characteristics within tumors and/or other treatment-related factors that are not captured by Oncotype DX tests and may be driving racial disparities in breast cancer. Furthermore, these results reinforce the need for greater racial diversity in clinical trial populations as researchers develop new tests such as the Oncotype DX, because there can be ancestry-related biological differences among patients from different population groups that influence the performance of these tests.

Treatment with Molecularly Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

Therapeutics directed to the molecules influencing cancer cell multiplication and survival target the cells within a tumor more precisely than cytotoxic chemotherapeutics that target all rapidly dividing cells, thereby limiting damage to healthy tissues. The greater precision of these molecularly targeted therapeutics tends to make them more effective and less toxic than cytotoxic chemotherapeutics. Molecularly targeted therapeutics have become the fourth pillar of cancer care and are not only saving the lives of patients with cancer, but also allowing these individuals to have a higher quality of life. The effective use of molecularly targeted therapeutics often requires tests called companion diagnostics. Companion diagnostics detect specific molecular abnormalities, e.g., genetic mutations within tumors, often referred to as biomarkers, to identify those patients who are most likely to benefit from the corresponding targeted therapy. This also allows patients identified as very unlikely to respond to forgo treatment and thus be spared any adverse side effects. The use of molecularly targeted therapeutics has ushered in a new era of precision medicine in which patients are treated based on their disease characteristics.

Unfortunately, many recent reports have highlighted striking disparities in the utilization of molecularly targeted treatments among patients from racial and ethnic minorities. For example, among women with stage III HER2 positive breast cancer, only 56 percent of Black patients compared to 74 percent of White patients received the HER2-targeted therapeutic trastuzumab (Herceptin) (605)Reeder-Hayes K, Peacock Hinton S, Meng K, Carey LA, Dusetzina SB. Disparities in Use of Human Epidermal Growth Hormone Receptor 2-Targeted Therapy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2003-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to another recent study, among women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer who are eligible for adjuvant endocrine therapy, 71 percent of AI/AN, 70 percent of Black, and 63 percent of Hispanic patients underutilize (i.e., fail to initiate or adhere to) treatment compared to 59 percent of White patients (606)Emerson MA, Achacoso NS, Benefield HC, Troester MA, Habel LA. Initiation and Adherence to Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy among Urban, Insured American Indian/Alaska Native Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer 2021;127:1847-56. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Yet another study reported that Black patients with NSCLC, are less likely to be tested to determine whether their cancer has an EGFR mutation compared with White patients and are less likely to be treated with the EGFR-targeted therapeutic erlotinib (Tarceva) (607)Palazzo LL, Sheehan DF, Tramontano AC, Kong CY. Disparities and Trends in Genetic Testing and Erlotinib Treatment among Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019;28:926-34. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Genetic testing of tumors to detect cancer-causing mutations is a critical step before receiving treatment with molecularly targeted therapeutics. Patients who are at high-risk for inherited cancers may also benefit from genetic testing. Unfortunately, recent reports indicate that the utilization of tumor genetic testing, overall, is suboptimal (608)Kehl KL, Lathan CS, Johnson BE, Schrag D. Race, Poverty, and Initial Implementation of Precision Medicine for Lung Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:431-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Rates of testing are particularly low among medically underserved populations, including racial and ethnic minorities. For example, a recent analysis of genetic testing rates among lung cancer patients showed that only 14 percent of Black patients received testing compared with 26 percent of White patients (204)Kehl KL, Lathan CS, Johnson BE, Schrag D. Race, Poverty, and Initial Implementation of Precision Medicine for Lung Cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2018;111:431-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similar trends have been noted in other types of cancer, including ovarian cancer (609)Kurian AW, Ward KC, Howlader N, Deapen D, Hamilton AS, Mariotto A, et al. Genetic Testing and Results in a Population-Based Cohort of Breast Cancer Patients and Ovarian Cancer Patients. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:1305-15. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Black women with ovarian cancer who report low income or discrimination at their place of work are significantly less likely to receive genetic testing (610)McBride CM, Pathak S, Johnson CE, Alberg AJ, Bandera EV, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, et al. Psychosocial Factors Associated with Genetic Testing Status among African American Women with Ovarian Cancer: Results from the African American Cancer Epidemiology Study. Cancer 2022;128:1252-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Reducing financial barriers and providing credible assurances that health information will not be disclosed and will not affect socioeconomic factors, such as employment, may increase uptake of genetic testing among these women. Additionally, educational interventions are needed to address biases among physicians’ perceived barriers to genetic testing among minority patients (611)Ademuyiwa FO, Salyer P, Tao Y, Luo J, Hensing WL, Afolalu A, et al. Genetic Counseling and Testing in African American Patients with Breast Cancer: A Nationwide Survey of US Breast Oncologists. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:4020-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Recent data indicate that there are racial and ethnic differences in the patterns of cancer-associated genetic alterations (see Figure 6). As one example, among patients with colorectal cancer age 50 and younger (often referred to as early-onset colorectal cancer), Black patients have higher rates of mutations in the KRAS gene (612)Hein DM, Deng W, Bleile M, Kazmi SA, Rhead B, De La Vega FM, et al. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Genomic Profiling of Early Onset Colorectal Cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2022;114(5):775-778. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This information can be critical in making treatment decisions, since many KRAS-targeted therapeutics are currently being evaluated in clinical trials and one therapeutic has recently received FDA approval (2)American Association for Cancer Research. Aacr Cancer Progress Report. [updated October 13, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Equally important among early-onset colorectal cancer patients is the detection of inherited mutations which may guide their treatment and/or future surveillance options. Unfortunately, a recent analysis of a diverse population of early-onset colorectal cancer patients indicated racial/ethnic differences in referral to and receipt of genetic testing (613)Gamble CR, Huang Y, Wright JD, Hou JY. Precision Medicine Testing in Ovarian Cancer: The Growing Inequity between Patients with Commercial Vs Medicaid Insurance. Gynecol Oncol 2021;162:18-23. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is also concerning that disparities in genetic testing rates have worsened in recent years, particularly between patients with and without private health insurance (207)Sheinson DM, Wong WB, Meyer CS, Stergiopoulos S, Lofgren KT, Flores C, et al. Trends in Use of Next-Generation Sequencing in Patients with Solid Tumors by Race and Ethnicity after Implementation of the Medicare National Coverage Determination. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2138219. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](613)Gamble CR, Huang Y, Wright JD, Hou JY. Precision Medicine Testing in Ovarian Cancer: The Growing Inequity between Patients with Commercial Vs Medicaid Insurance. Gynecol Oncol 2021;162:18-23. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Receiving care at equal-access health care systems, for instance the Veterans Health Administration, the U.S. military health care system, has been shown to reduce disparities in genetic testing among underserved populations (614)Vargason AB, Turner CE, Shriver CD, Ellsworth RE. Genetic Testing in Non-Hispanic Black Women with Breast Cancer Treated within an Equal-Access Healthcare System. Genetics in Medicine 2022;24:232-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Therefore, future public health policies must aim at equitable access to the benefits of precision medicine including tumor genetic testing and the receipt of molecularly targeted therapeutics for all patients.

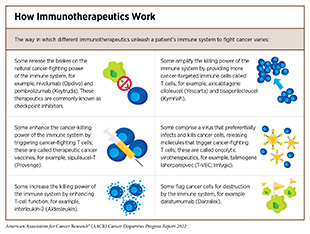

Cancer immunotherapeutics work by unleashing the power of a patient’s immune system to fight cancer the way it fights pathogens like the virus that causes flu and the bacterium that causes strep throat. There are many ways by which immunotherapeutics can eliminate cancer (see sidebar on How Immunotherapeutics Work). Immunotherapy has emerged as the fifth pillar of cancer care and as one the most exciting new approaches to cancer treatment. This is, in part, because many patients with metastatic cancer who have been treated with these revolutionary treatments have had remarkable and durable responses. In fact, the rapid advances in the field of immunotherapeutics have transformed the treatment landscape for patients with formerly intractable cancers such as NSCLC or metastatic melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. As reported in AACR Cancer Progress Report 2021, dramatic reductions in lung cancer and melanoma death rates in recent years, due in part to molecularly targeted therapeutics and immunotherapeutics, are largely responsible for the steady decline in overall age-adjusted U.S. cancer death rates (2)American Association for Cancer Research. Aacr Cancer Progress Report. [updated October 13, 2021, cited 2022 April 22]..

Despite the high efficacy of immunotherapies, less than half of all patients with advanced melanoma and less than 10 percent of patients with NSCLC receive treatment with these lifesaving therapeutics (615)Ashrafzadeh S, Asgari MM, Geller AC. The Need for Critical Examination of Disparities in Immunotherapy and Targeted Therapy Use among Patients with Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1115-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are sociodemographic disparities in the utilization of immunotherapies. For example, according to a recent analysis, patients with metastatic melanoma are less likely to receive immunotherapy if they are older, uninsured or lack private insurance, receive treatment at a community setting, or live in zip codes with low level of education (616)Rai P, Shen C, Kolodney J, Kelly KM, Scott VG, Sambamoorthi U. Factors Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Use among Older Adults with Late-Stage Melanoma: A Population-Based Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e24782. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](617)Moyers JT, Patel A, Shih W, Nagaraj G. Association of Sociodemographic Factors with Immunotherapy Receipt for Metastatic Melanoma in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2015656. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, data show that Black patients with melanoma may experience a longer time to immunotherapy initiation compared to White patients (618)Tripathi R, Archibald LK, Mazmudar RS, Conic RRZ, Rothermel LD, Scott JF, et al. Racial Differences in Time to Treatment for Melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2020;83:854-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similarly, NSCLC patients who are Black, live in less-educated areas, or are uninsured or lack private health insurance are less likely to receive immunotherapy (208)Verma V, Haque W, Cushman TR, Lin C, Simone CBI, Chang JY, et al. Racial and Insurance-Related Disparities in Delivery of Immunotherapy-Type Compounds in the United States. Journal of Immunotherapy 2019;42:55-64. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It should be noted that treatment responses and toxic side effects from immunotherapies might differ among patients from different racial and ethnic populations (619)Olsen TA, Martini DJ, Goyal S, Liu Y, Evans ST, Magod B, et al. Racial Differences in Clinical Outcomes for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients Treated with Immune-Checkpoint Blockade. Frontiers in Oncology 2021;11:701345. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](620)Thompson LL, Pan CX, Chang MS, Krasnow NA, Blum AE, Chen ST. Impact of Ethnicity on the Diagnosis and Management of Cutaneous Toxicities from Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021;84:851-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is critical that ongoing research continue to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and utilization of these therapeutics among racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved patient populations through increased participation in clinical trials as well as from assessing data in real-world practice (see Achieving Equity in Clinical Cancer Research).