Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors

In this section, you will learn:

- Decades of systemic inequities and social injustices have led to adverse differences in social determinants of health causing a disproportionately higher burden of cancer risk factors among U.S. racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations.

- In the United States, four out of 10 cancer cases are associated with preventable risk factors.

- Not using tobacco is one of the most effective ways a person can prevent cancer from developing.

- Nearly 20 percent of U.S. cancer diagnoses are related to excess body weight, alcohol intake, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity.

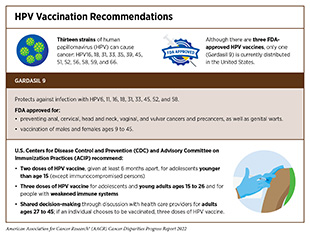

- Nearly all cases of cervical cancer, as well as many cases of head and neck and anal cancers, can be prevented by HPV vaccination.

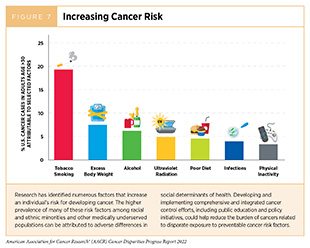

Factors that increase a person’s chances of developing cancer are referred to as cancer risk factors. Decades of research have led to the identification of numerous cancer risk factors (Figure 7) such as tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, obesity, infection with certain pathogens, and exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Given that several of these risks can be avoided, many cases of cancer can potentially be prevented. In the United States, the most recent data available indicate that more than 40 percent of all new cancer cases diagnosed in 2014 were attributable to preventable risk factors (210)Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and Number of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Emerging data indicate that certain cancer risk factors are also associated with worse outcomes after a cancer diagnosis, including development of secondary cancers (211)Sung H, Hyun N, Leach CR, Yabroff KR, Jemal A. Association of First Primary Cancer with Risk of Subsequent Primary Cancer among Survivors of Adult-Onset Cancers in the United States. JAMA 2020;324:2521-35. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](212)Petrelli F, Cortellini A, Indini A, Tomasello G, Ghidini M, Nigro O, et al. Association of Obesity with Survival Outcomes in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e213520. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition, many cancer risk factors contribute to other chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases, and diabetes. Therefore, reducing or eliminating exposure has the potential to reduce the burden of cancer as well as several other diseases.

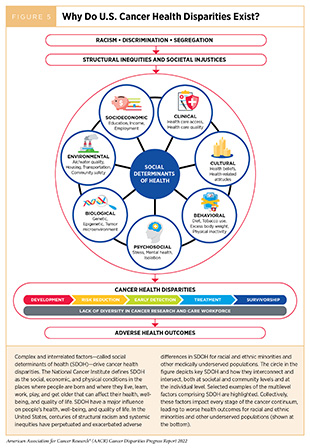

Systemic Inequities and Social Injustices

In the United States, many of the greatest reductions in cancer morbidity and mortality have been achieved through implementation of effective public education and policies in cancer prevention. For example, such initiatives have helped reduce cigarette smoking rates among U.S. adults by 70 percent from 1965 to 2020 (213)Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco Product Use among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](214)National Center for Chronic Disease P, Health Promotion Office on S, Health. Reports of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], which has contributed significantly to the dramatic decline in overall U.S. cancer mortality rates (1)Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2022;72:7-33. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, long-standing inequities in numerous SDOH (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities; and Figure 5) contribute to significant disparities in the burden of preventable cancer risk factors among socially, economically, and geographically disadvantaged populations. These disparities stem from decades of structural, social, and institutional injustices and not only place disadvantaged populations in unfavorable living environments (e.g., with higher exposure to environmental carcinogens) (see Social and Built Environments) but also contribute to behaviors that increase cancer risk (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption, or unhealthy diet) (215)Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, Yabroff KR, Guerra CE, Wender RC. Understanding and Addressing Social Determinants to Advance Cancer Health Equity in the United States: A Blueprint for Practice, Research, and Policy. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2020;70:31-46. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

It must be noted that an individual’s personal behaviors and exposures are strongly influenced by living environments. For example, lack of quality housing (e.g., those without smoke-free policies) may expose disadvantaged communities to high levels of secondhand smoke, a known cause of lung cancer. Moreover, the neighborhoods where socioeconomically disadvantaged populations reside are often characterized by food deserts with reduced availability of healthy food options such as fresh fruits and vegetables, and limited outdoor space for recreation and/or exercise. These living environments create barriers to behaviors that are important in lowering cancer risk, such as maintaining a healthy weight, eating a balanced diet, and being physically active. Socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are also more likely to be in less favorable locations such as in close proximity to highways and busy roads, which increase exposure of residents to air pollution (see Social and Built Environments). It is also important to consider that socioeconomic and geographic disadvantages intersect with other population characteristics such as race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability status, among others. As one example, individuals with disabilities, who may have fewer occupational opportunities and lower income, also have a higher prevalence of smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity (13)Islami F, Guerra CE, Minihan A, Yabroff KR, Fedewa SA, Sloan K, et al. American Cancer Society’s Report on the Status of Cancer Disparities in the United States, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:112-43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is imperative that public health experts prioritize cancer prevention efforts that account for the complex and interrelated factors across institutional, social, and individual levels, which influence personal risk behavior and disparate health outcomes. Furthermore, there is an urgent need for all stakeholders in the medical research community to come together and develop better strategies which enhance the dissemination of our current knowledge of cancer prevention and implement evidence-based interventions for reducing the burden of cancer for everyone.

Tobacco Use

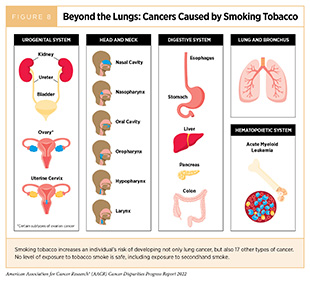

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer. Smoking increases the risk of developing at least 17 different types of cancer in addition to lung cancer (Figure 8), because it exposes individuals to many harmful chemicals that cause genetic and epigenetic alterations leading to cancer development (2)American Association for Cancer Research. Aacr Cancer Progress Report. [updated October 13, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Fortunately, quitting at any age reduces the risk of cancer occurrence and cancer-related death. In addition, smoking cessation also reduces risk for many adverse health effects including cardiovascular diseases and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), among others (216)United States Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon G, National Center for Chronic Disease P, Health Promotion Office on S, Health. Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Thus, one of the most effective ways a person can lower the risk of developing cancer and other smoking-related conditions is to avoid or eliminate tobacco use.

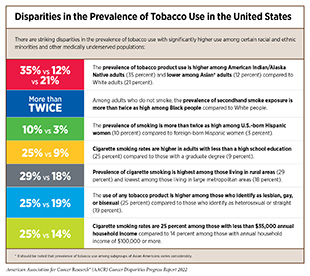

Thanks to the implementation of nationwide comprehensive tobacco control initiatives, cigarette smoking among U.S. adults has been declining steadily. In 2020, the most recent year for which such data are available, 12.5 percent of U.S. adults age 18 and older smoked cigarettes, a significant decline from 42.4 percent of adults in 1965 (213)Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco Product Use among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](214)National Center for Chronic Disease P, Health Promotion Office on S, Health. Reports of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Exposure to secondhand smoke, which increases the risk of lung cancer among nonsmokers, has also dropped substantially over the past three decades (217)Tsai J, Homa DM, Gentzke AS, Mahoney M, Sharapova SR, Sosnoff CS, et al. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke among Nonsmokers – United States, 1988-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1342-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Despite these positive trends, more than 47 million adults in the United States reported using a tobacco product in 2020 (213)Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco Product Use among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It has been documented that most adult users initiate smoking in their youth. Therefore, it is concerning that 5.2 million high school students and 1.34 million middle school students in the United States used some type of tobacco product in 2021 (218)Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, et al. Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors among Middle and High School Students – National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71:1-29. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, there are striking sociodemographic disparities in the use of tobacco products as well as in the exposure to secondhand smoke (see sidebar on Disparities in the Prevalence of Tobacco Use in the United States). Overall, tobacco use is higher among residents of the U.S. Midwest and South compared to the rest of the country; among individuals with lower levels of household income; among adults who lack private health insurance; and among individuals with disabilities or serious psychological distress (213)Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco Product Use among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition, tobacco use is higher among American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults compared to any other racial or ethnic groups. The prevalence of cigarette smoking among AI/AN adults varies by geographic region, which leads to geographic variation in lung cancer incidence rates among these populations (219)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lung Cancer Incidence in the American Indian and Alaska Native Population, United States Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Areas—2012–2016. [updated October 22, 2019, cited 2022 April 22]..

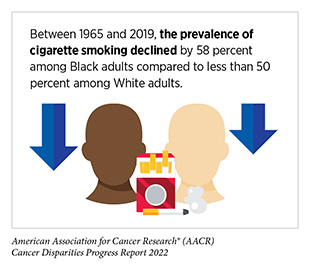

Although Black adults smoke at comparable levels to NHW adults, tobacco-related cancer morbidity and mortality rates are disproportionately higher among this population (220)Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer Statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians;2022;72:202-229. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to a recent report, even at relatively low levels of smoking intensity, Black as well as Native Hawaiian adults who smoke have significantly higher risk of lung cancer compared to Japanese Americans, Hispanic, and White adults (223)Stram DO, Park SL, Haiman CA, Murphy SE, Patel Y, Hecht SS, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Lung Cancer Incidence in the Multiethnic Cohort Study: An Update. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2019;111:811-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The reason for the differential risk is not fully understood and is likely to be multifactorial, including socioeconomic differences impacting access to quality care, prevalence of additional risk factors such as obesity, exposure to secondhand smoke, and prevalence of mentholated cigarette use. In addition, there is emerging evidence that current measures of nicotine intake and dependence and smoke exposure may underestimate the risk to Black adults who smoke (224)Ho JTK, Tyndale RF, Baker TB, Amos CI, Chiu A, Smock N, et al. Racial Disparities in Intensity of Smoke Exposure and Nicotine Intake among Low-Dependence Smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2021;221:108641. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to recent data, tobacco-related cancer mortality in the U.S. is declining rapidly because of significant reductions in smoking over the past five decades (1)Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2022;72:7-33. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The steeper reductions in smoking initiation in recent years, especially among Black men, have led to a faster decline in tobacco-related cancer mortality among Black people compared to White people (220)Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer Statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians;2022;72:202-229. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Smoking cessation through medications or counseling can lower risk for cancer development or death from cancer (226)Department of Health and Human Services. What You Need to Know About Quitting Smoking: Advice from the Surgeon General. [updated December 10, 2020, cited 2022 April 29].. Unfortunately, the rate of successful smoking cessation is lower among Black and AI/AN adults compared to White adults (227)Carroll DM, Cole A. Racial/Ethnic Group Comparisons of Quit Ratios and Prevalences of Cessation-Related Factors among Adults Who Smoke with a Quit Attempt. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 2022;48:58-68. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], even though Black adults are more likely to report their willingness to stop smoking compared to other racial and ethnic groups (220)Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer Statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians;2022;72:202-229. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similarly, despite a higher prevalence of smoking in rural areas compared to urban areas, a recent study reported that rural smokers were nearly three times less likely than their urban counterparts to receive any smoking cessation treatment (228)Ramsey AT, Baker TB, Pham G, Stoneking F, Smock N, Colditz GA, et al. Low Burden Strategies Are Needed to Reduce Smoking in Rural Healthcare Settings: A Lesson from Cancer Clinics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020;17:1728. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study which examined the role of health care access in the receipt of smoking cessation advice from health care providers found that among those with limited access to health care, Hispanic smokers had significantly lower odds of being advised to stop smoking compared to NHW smokers (229)Li L, Zhan S, Hu L, Wilson KM, Mazumdar M, Liu B. Examining the Role of Healthcare Access in Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Receipt of Provider-Patient Discussions About Smoking: A Latent Class Analysis. Prev Med 2021;148:106584. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Therefore, increasing health insurance coverage and reducing additional health care access barriers may facilitate provider-patient discussion and promote tobacco cessation among minority populations. Further progress in reducing smoking and smoking-related cancer burden will require the implementation of culturally tailored, evidence-based, and equitably accessible smoking cessation interventions. It is vital for these interventions to be available to all populations irrespective of their geographic location or socioeconomic status.

Flavored tobacco products, such as mentholated cigarettes, pose a significant public health risk. People who smoke menthol cigarettes report increased nicotine dependence and reduced smoking cessation compared to those who smoke nonmenthol cigarettes (230)Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS, Gagosian SY, Abrams DB. Menthol Cigarettes and the Public Health Standard: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2017;17:983. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The prevalence of menthol cigarette use is higher among individuals who are Black, from the SGM population, or from low socioeconomic background (220)Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer Statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians;2022;72:202-229. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](231)Ehlke SJ, Ganz O, Kendzor DE, Cohn AM. Differences between Adult Sexual Minority Females and Heterosexual Females on Menthol Smoking and Other Smoking Behaviors: Findings from Wave 4 (2016–2018) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Addictive Behaviors 2022;129:107265. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](232)Usidame B, Hirschtick J, Zavala-Arciniega L, Mattingly DT, Patel A, Meza R, et al. Exclusive and Dual Menthol/Non-Menthol Cigarette Use with Ends among Adults, 2013–2019. Preventive Medicine Reports 2021;24:101566. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For example, based on a recent report, lesbian and bisexual females are 27 percent more likely to initiate smoking with a menthol cigarette and 24 percent more likely to report menthol cigarette use compared to heterosexual females (231)Ehlke SJ, Ganz O, Kendzor DE, Cohn AM. Differences between Adult Sexual Minority Females and Heterosexual Females on Menthol Smoking and Other Smoking Behaviors: Findings from Wave 4 (2016–2018) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Addictive Behaviors 2022;129:107265. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition, certain medically underserved populations not only use menthol cigarettes at a disproportionately higher rate, but also exhibit dual menthol cigarette and other tobacco product use (232)Usidame B, Hirschtick J, Zavala-Arciniega L, Mattingly DT, Patel A, Meza R, et al. Exclusive and Dual Menthol/Non-Menthol Cigarette Use with Ends among Adults, 2013–2019. Preventive Medicine Reports 2021;24:101566. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Among people who smoke menthol cigarettes, Black individuals have lower odds of smoking cessation compared to White or Hispanic individuals. Furthermore, Black and low-income communities are at a higher risk of being exposed to targeted advertisements, including storefront ads and price promotions, specifically for menthol cigarettes (233)Cook S, Hirschtick JL, Patel A, Brouwer A, Jeon J, Levy DT, et al. A Longitudinal Study of Menthol Cigarette Use and Smoking Cessation among Adult Smokers in the US: Assessing the Roles of Racial Disparities and E-Cigarette Use. Prev Med 2022;154:106882. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](234)Smiley SL, Cho J, Blackman KCA, Cruz TB, Pentz MA, Samet JM, et al. Retail Marketing of Menthol Cigarettes in Los Angeles, California: A Challenge to Health Equity. Prev Chronic Dis 2021;18:E11. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Thus, tobacco control policies that restrict menthol cigarette sales including restrictive laws and menthol bans are a potential policy target for reducing tobacco-related health disparities. As one example, a comprehensive flavor ban on tobacco products in Massachusetts was associated with a significant reduction in state-level menthol— and all— cigarette sales (235)Asare S, Majmundar A, Westmaas JL, Bandi P, Xue Z, Jemal A, et al. Association of Cigarette Sales with Comprehensive Menthol Flavor Ban in Massachusetts. JAMA Internal Medicine 2022;182:231-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Therefore, it is encouraging that FDA has proposed a nationwide menthol ban that will restrict the manufacturing, marketing, and sale of menthol cigarettes (see Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Prevention(236)U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Fda Commits to Evidence-Based Actions Aimed at Saving Lives and Preventing Future Generations of Smokers. [updated April 29, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Ongoing research is needed to monitor the effectiveness of such policies and to address potential limitations (e.g., menthol smokers switching to unflavored cigarettes) that can undermine the effectiveness of the policies.

Historically, tobacco companies have marketed their products more heavily to minority and low-income populations. Tobacco retailer densities are highly concentrated in neighborhoods with more Black and Hispanic residents (237)Mills SD, Kong AY, Reimold AE, Baggett CD, Wiesen CA, Golden SD. Sociodemographic Disparities in Tobacco Retailer Density in the United States, 2000–2017. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2022 [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and these sociodemographic disparities in marketing contribute to inequities in smoking and the burden of smoking-related diseases. Therefore, identifying communities that need to be prioritized for tobacco-restrictive policies and regulation and rapidly implementing evidence-based interventions are urgent public health needs. Increasing cigarette prices via tobacco tax increases is another approach to reduce tobacco use and prevent smoking initiation (214)National Center for Chronic Disease P, Health Promotion Office on S, Health. Reports of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2014. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent analysis reported that a one dollar increase in cigarette pack price corresponded with a 72 percent decrease in smoking initiation and a 70 percent decrease in progression to daily smoking (238)Parks MJ, Patrick ME, Levy DT, Thrasher JF, Elliott MR, Fleischer NL. Cigarette Pack Price and Its within-Person Association with Smoking Initiation, Smoking Progression, and Disparities among Young Adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2022;24:519-28. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Whether such interventions can reduce the sociodemographic disparities in smoking rates and related illnesses needs to be evaluated (239)Parks MJ, Patrick ME, Levy DT, Thrasher JF, Elliott MR, Fleischer NL. Tobacco Taxation and Its Prospective Impact on Disparities in Smoking Initiation and Progression among Young Adults. J Adolesc Health 2021;68:765-72. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Nonetheless, these data clearly highlight the urgent need for all stakeholders to work together to develop and implement evidence-based, population-level interventions to reduce the burden of tobacco use for racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations.

The use of other combustible tobacco products (e.g., cigars), smokeless tobacco products (e.g., chewing tobacco and snuff), and waterpipes (hookahs) is also associated with adverse health outcomes including cancer (241)Christensen CH, Rostron B, Cosgrove C, Altekruse SF, Hartman AM, Gibson JT, et al. Association of Cigarette, Cigar, and Pipe Use with Mortality Risk in the US Population. JAMA Internal Medicine 2018;178:469-76. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) has increased dramatically in the past ten years, and their long-term health impacts are unknown (242)National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Health, Medicine D, Board on Population H, Public Health P, et al. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. In: Eaton DL, Kwan LY, Stratton K, editors. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US);2018. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While promoted by manufacturers as a smoking cessation tool, the benefit of e-cigarettes in cessation is currently unclear (2)American Association for Cancer Research. Aacr Cancer Progress Report. [updated October 13, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. It is known, however, that in addition to nicotine, a highly addictive substance, e-cigarettes contain and emit numerous potentially toxic chemicals including heavy metals and volatile organic compounds. Therefore, an alarming trend in recent years is the growing popularity of e-cigarettes among U.S. youth and young adults. These trends are concerning because the use of e-cigarettes increases the probability of youth or young adults transitioning to conventional cigarettes (2)American Association for Cancer Research. Aacr Cancer Progress Report. [updated October 13, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Additionally, there are emerging data showing that the use of e-cigarettes may cause inflammation and disease (243)Tommasi S, Pabustan N, Li M, Chen Y, Siegmund KD, Besaratinia A. A Novel Role for Vaping in Mitochondrial Gene Dysregulation and Inflammation Fundamental to Disease Development. Scientific reports 2021;11:22773. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Currently the NHW population has higher use of e-cigarettes compared to other racial and ethnic groups (213)Cornelius ME, Loretan CG, Wang TW, Jamal A, Homa DM. Tobacco Product Use among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](218)Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Cornelius M, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Sawdey MD, et al. Tobacco Product Use and Associated Factors among Middle and High School Students – National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71:1-29. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Continuing research on the health effects of e-cigarettes and their use across different population groups is necessary to ensure that use of e-cigarettes does not increase existing disparities in smoking behavior and health outcomes. Additionally, any potential efficacy of these products for supporting smoking cessation must be investigated in randomized clinical trials with diverse representation of participants.

Adverse influence of SDOH (Figure 5) (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities including lack of homeownership, lower income, and greater neighborhood problems may significantly contribute to racial disparities in smoking cessation (245)Nollen NL, Mayo MS, Sanderson Cox L, Benowitz NL, Tyndale RF, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Factors That Explain Differences in Abstinence between Black and White Smokers: A Prospective Intervention Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:1078-87. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additional factors such as dwellings with higher population density, increased volume of tobacco retailers, and lack of smoke free housing laws, increase smoking initiation and exposure to secondhand smoke in underserved neighborhoods. These factors also make it more challenging for residents to quit smoking. Lack of quality health care coverage can reduce access to FDA-approved medications or evidence-based counseling, both of which are known to help with smoking cessation. Collectively, these challenges highlight the need for multilevel (institutional, community, and individual) interventions to address disparities in tobacco use. Policy interventions can reduce tobacco-related cancer disparities by preventing people from starting to smoke, helping people quit smoking, and reducing exposure to secondhand smoke. This can be accomplished through enacting comprehensive smoke-free laws, increasing taxes on tobacco products, reducing predatory advertising, and offering comprehensive and evidence-based cessation services.

Going forward, it is vital that tobacco-related policies provide equal benefit to everyone, particularly to vulnerable populations including racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved population groups. For instance, smoking cessation clinical trials must implement strategies to recruit a sociodemographically diverse cohort of participants to ensure that the interventions are effective in diverse populations (246)Asfar T, Koru-Sengul T, Antoni MA, Dorsey A, Ruano Herreria EC, Lee DJ, et al. Recruiting Racially and Ethnically Diverse Smokers Seeking Treatment: Lessons Learned from a Smoking Cessation Randomized Clinical Trial. Addict Behav 2022;124:107112. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is also vital that the interventions be culturally sensitive. Two recent studies showed that tailored interventions were effective in discouraging smoking among urban American Indian youth and encouraging smoking cessation among Spanish-speaking Hispanics in the United States (247)Yzer M, Rhodes K, Nagler RH, Joseph A. Effects of Culturally Tailored Smoking Prevention and Cessation Messages on Urban American Indian Youth. Prev Med Rep 2021;24:101540. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](248)Simmons VN, Sutton SK, Medina-Ramirez P, Martinez U, Brandon KO, Byrne MM, et al. Self-Help Smoking Cessation Intervention for Spanish-Speaking Hispanics/Latinxs in the United States: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cancer 2022;128:984-94. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, the NCI’s Cancer Center Cessation Initiatives is evaluating numerous innovative approaches to reduce the disproportionate tobacco-related burden and eliminate tobacco-related cancer disparities (249)The Cancer Center Cessation Initiative Diversity E, and Inclusion Working Group Members. Integrating Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Approaches into Treatment of Commercial Tobacco Use for Optimal Cancer Care Delivery. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:s4-s7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](250)Group TCCCITW. Telehealth Delivery of Tobacco Cessation Treatment in Cancer Care: An Ongoing Innovation Accelerated by the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021;19:s21-s4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Body Weight, Diet, and Physical Activity

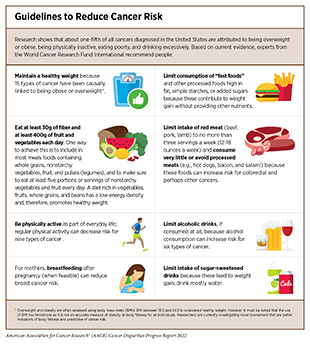

Nearly 20 percent of new cancer cases and 16 percent of cancer deaths in U.S. adults are attributable to a combination of excess body weight, lack of healthful diet, physical inactivity, and alcohol consumption (210)Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and Number of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Therefore, maintaining a healthy weight, being physically active, consuming a balanced diet, and avoiding alcohol are effective strategies for individuals to lower their risk of developing or dying from cancer (see sidebar on Guidelines to Reduce Cancer Risk). In the United States, decades of systemic and structural racism have contributed to adverse differences in SDOH in racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations (see Factors That Drive Cancer Health Disparities. Racial inequality in income, employment, and homeownership, stemming from structural racism, in turn, has been associated with obesity (251)Bell CN, Kerr J, Young JL. Associations between Obesity, Obesogenic Environments, and Structural Racism Vary by County-Level Racial Composition. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019;16:861. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](252)Mackey ER, Burton ET, Cadieux A, Getzoff E, Santos M, Ward W, et al. Addressing Structural Racism Is Critical for Ameliorating the Childhood Obesity Epidemic in Black Youth. Child Obes 2022;18:75-83. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. SDOH can shape an individual’s education, employment, financial security, and available choices around healthful diet and physical activity through psychosocial influences such as stress as well as environmental influences such as the availability of fresh food and green spaces in the community. Collectively, these factors may impact body weight and subsequent health outcomes.

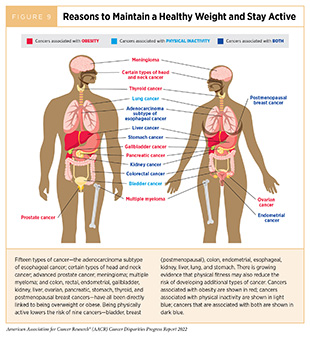

Being overweight or obese as an adult increases a person’s risk for 15 types of cancer; being physically active reduces risk for nine types of cancer (Figure 9). Identifying the underlying mechanisms by which obesity, unhealthy diet, alcohol, and physical inactivity increase cancer risk and quantifying the magnitude of such risks are areas of active research. Accumulating evidence indicates a role of chronic inflammation and the immune system in mediating the effects of obesity on cancer development (262)Rathmell JC. Obesity, Immunity, and Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2021;384:1160-2. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](263)Foley JF. Obesity and Antitumor Immunity. Science Signaling 2022;15:eabq0080. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are significant differences in the quality of diet, prevalence of obesity, physical activity, and alcohol consumption among different populations (see sidebar on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obesity, Diet, and Physical Activity in the United States) and several cancers with a higher burden among racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations are associated with obesity and physical inactivity. Emerging data indicate that the association between obesity and cancer risk may vary among different racial and ethnic groups (264)Brown JC, Yang S, Mire EF, Wu X, Miele L, Ochoa A, et al. Obesity and Cancer Death in White and Black Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Obesity 2021;29:2119-25. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](265)Ballinger TJ, Jiang G, Shen F, Miller KD, Sledge GW, Jr., Schneider BP. Impact of African Ancestry on the Relationship between Body Mass Index and Survival in an Early-Stage Breast Cancer Trial. Cancer 2022;128:2174-2181. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, the distribution of body fat can vary by racial or ethnic group, and this distribution may also affect cancer risk. Although the increased cancer risk associated with excess body weight and weight gain is clear, mechanisms underlying the variation in risk among different populations are not fully understood. Ongoing research is investigating the biological underpinnings including ancestry-related genetic alterations that may contribute to the differential susceptibility of racial and ethnic groups to obesity-related diseases such as cancer (266)Guha A, Wang X, Harris RA, Nelson AG, Stepp D, Klaassen Z, et al. Obesity and the Bidirectional Risk of Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases in African Americans: Disparity Vs. Ancestry. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021;8:761488. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The prevalence of obesity has been rising steadily in the United States. In 2018, which is the most recent year for which data are available, 21 percent of youth ages 12 to 19, and 42 percent of adults ages 20 and older were considered obese (272)Trust for America’s Health. The State of Obesity 2020: Better Policies for a Healthier America. [updated May 5, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].(273)Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, Freedman DS, Carroll MD, Gu Q, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence by Race and Hispanic Origin-1999-2000 to 2017-2018. Jama 2020;324:1208-10. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are, however, notable disparities based on geography and levels of income, as well as race/ethnicity (see sidebar on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Obesity, Diet, and Physical Activity in the United States). Studies have shown that socioeconomic inequalities, which are driven largely by structural and social inequities, are associated with obesity (274)Trust for America’s Health. State of Obesity 2021: Better Policies for a Healthier America. [updated November 5, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. For example, according to a recent study, favorable social and built environment in a neighborhood can promote healthy weight maintenance during adolescence and young adulthood (275)Niu L, Hoyt LT, Pickering S, Nucci-Sack A, Salandy A, Shankar V, et al. Neighborhood Profiles and Body Mass Index Trajectory in Female Adolescents and Young Adults. Journal of Adolescent Health 2021;69:1024-31. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It should be noted that focusing on obesity in early life is key to reducing disparities in obesity and cancer because risk of adult obesity is greater among individuals who were obese as children. Another recent report indicated that among U.S. adults, long-term improvement in neighborhood socioeconomic status is associated with lower risk while long-term decline in neighborhood socioeconomic status is associated with higher risks for excessive weight gain among residents (276)Zhang D, Bauer C, Powell-Wiley T, Xiao Q. Association of Long-Term Trajectories of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status with Weight Change in Older Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2036809. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A variety of factors such as absence of grocery stores and prevalence of fast-food restaurants in the neighborhood, as well as social contexts, such as chronic stress, may contribute to the environment-induced effect on obesity (274)Trust for America’s Health. State of Obesity 2021: Better Policies for a Healthier America. [updated November 5, 2021, cited 2022 April 22]..

One major concern among U.S. public health experts is the significantly higher prevalence of obesity among rural adults. There are complex and interrelated factors that contribute to this disparity (277)Okobi OE, Ajayi OO, Okobi TJ, Anaya IC, Fasehun OO, Diala CS, et al. The Burden of Obesity in the Rural Adult Population of America. Cureus 2021;13:e15770. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Rural residents are less likely to be physically active and eat healthily compared to urban residents. Rural Americans may also have lower income and lack access to resources such as healthy food or recreational facilities to assist them in weight reduction compared to urban residents (277)Okobi OE, Ajayi OO, Okobi TJ, Anaya IC, Fasehun OO, Diala CS, et al. The Burden of Obesity in the Rural Adult Population of America. Cureus 2021;13:e15770. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Further research to gain a comprehensive understanding of the major contributors of obesity among rural residents is needed to develop interventions and policies that can effectively reduce cancer risks and cancer health disparities among rural residents, who account for 15 percent of the U.S. population (221)National Cancer Institute. Rural-Urban Disparities in Cancer. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22]..

There are emerging data showing that weight loss interventions may lower the future risk of certain obesity-related cancers (278)Tao W, Santoni G, von Euler-Chelpin M, Ljung R, Lynge E, Pukkala E, et al. Cancer Risk after Bariatric Surgery in a Cohort Study from the Five Nordic Countries. Obes Surg 2020;30:3761-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](280)docwirenews. Weight Loss Surgery Cuts Risk of Pancreatic Cancer for Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. [updated October 14, 2020, cited 2022 April 22].. Eliminating disparities in obesity and obesity-related cancers necessitates further research to identify culturally tailored, community-based interventions that can be implemented at population levels, especially in low-resource and diverse settings. In this regard, a lifestyle-based obesity intervention delivered in an underserved, low-income primary care population resulted in clinically significant weight loss among participants within 24 months (281)Katzmarzyk PT, Martin CK, Newton RL, Apolzan JW, Arnold CL, Davis TC, et al. Weight Loss in Underserved Patients—a Cluster-Randomized Trial. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;383:909-18. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Yet another lifestyle program addressing obesity among U.S. Mexicans identified family as a primary motivator for behavior change while barriers to intervention adoption included time and workplace-related factors (282)Leng J, Lui F, Narang B, Puebla L, González J, Lynch K, et al. Developing a Culturally Responsive Lifestyle Intervention for Overweight/Obese U.S. Mexicans. J Community Health 2022;47:28-38. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is evidence that weight control programs need to be designed with population-specific incentives to maximize population reach and reduce health disparities (283)You W, Yuan Y, Boyle KJ, Michaud TL, Parmeter C, Seidel RW, et al. Examining Ways to Improve Weight Control Programs’ Population Reach and Representativeness: A Discrete Choice Experiment of Financial Incentives. Pharmacoecon Open 2022;6:193-210. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. To reduce the burden of cancer in racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations, implementation of evidence-based interventions to address obesity must be a top priority among U.S. public health efforts. Such interventions must also address weight-based discrimination, especially within health care settings. Weight stigma has been related to avoidance or delay in receiving health care (284)Alberga AS, Edache IY, Forhan M, Russell-Mayhew S. Weight Bias and Health Care Utilization: A Scoping Review. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2019;20:e116. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] and negative health outcomes (285)Tomiyama AJ, Carr D, Granberg EM, Major B, Robinson E, Sutin AR, et al. How and Why Weight Stigma Drives the Obesity ‘Epidemic’ and Harms Health. BMC Medicine 2018;16:123. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](286)Prunty A, Clark MK, Hahn A, Edmonds S, O’Shea A. Enacted Weight Stigma and Weight Self Stigma Prevalence among 3821 Adults. Obes Res Clin Pract 2020;14:421-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

One key public policy aimed at reducing obesity is the introduction of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages in several local jurisdictions in the United States (121)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2021-2022. [updated January 12, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Sugar-sweetened beverages are a major contributor to caloric intake among U.S. youth and adults, and there are some emerging data indicating that consumption may be associated with an increased risk of cancer incidence and mortality (287)Koyratty N, McCann SE, Millen AE, Nie J, Trevisan M, Freudenheim JL. Sugar-Sweetened Soda Consumption and Total and Breast Cancer Mortality: The Western New York Exposures and Breast Cancer (Web) Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2021;30:945-52. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](288)Hur J, Otegbeye E, Joh HK, Nimptsch K, Ng K, Ogino S, et al. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake in Adulthood and Adolescence and Risk of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer among Women. Gut 2021;70:2330-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](289)Chazelas E, Srour B, Desmetz E, Kesse-Guyot E, Julia C, Deschamps V, et al. Sugary Drink Consumption and Risk of Cancer: Results from Nutrinet-Santé Prospective Cohort. Bmj 2019;366:l2408. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](290)Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption among U.S. Youth, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief 2017:1-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](291)Rosinger A, Herrick K, Gahche J, Park S. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption among U.S. Adults, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief 2017:1-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](292)Joh HK, Lee DH, Hur J, Nimptsch K, Chang Y, Joung H, et al. Simple Sugar and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake During Adolescence and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Precursors. Gastroenterology 2021;161:128-42.e20. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Thus, it is encouraging that the prevalence of heavy sugar-sweetened beverage intake (consumption of 500 kcal or more from sugar-sweetened beverages per day) has declined among U.S. children and adults in recent years (293)Jiang N, Yi SS, Russo R, Bu DD, Zhang D, Ferket B, et al. Trends and Sociodemographic Disparities in Sugary Drink Consumption among Adults in New York City, 2009–2017. Preventive Medicine Reports 2020;19:101162. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](294)Vercammen KA, Moran AJ, Soto MJ, Kennedy-Shaffer L, Bleich SN. Decreasing Trends in Heavy Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption in the United States, 2003 to 2016. J Acad Nutr Diet 2020;120:1974-85.e5. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, there are persistent disparities in consumption across racial and ethnic populations, with Black, Mexican American, and other Hispanic adults and children being more likely to drink sugar-sweetened beverages than their White counterparts (293)Jiang N, Yi SS, Russo R, Bu DD, Zhang D, Ferket B, et al. Trends and Sociodemographic Disparities in Sugary Drink Consumption among Adults in New York City, 2009–2017. Preventive Medicine Reports 2020;19:101162. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](295)Health Food America. Sugary Drinks in America: Who’s Drinking What and How Much? [updated June 2018, cited 2022 April 22].(296)Mendez MA, Miles DR, Poti JM, Sotres-Alvarez D, Popkin BM. Persistent Disparities over Time in the Distribution of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake among Children in the United States. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018;109:79-89. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers estimate that sugar-sweetened beverage taxes can be cost effective and can potentially result in significant health gains as well as economic benefits for all populations including those who experience cancer health disparities (297)Du M, Griecci CF, Kim DD, Cudhea F, Ruan M, Eom H, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of a National Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax to Reduce Cancer burdens and Disparities in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2020;4:pkaa073. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Continued research is necessary to identify effective policies related to food and nutrition that maximize health benefits and to evaluate the long-term effects of these policies on obesity and obesity-related health outcomes such as cancer.

Complex and interrelated factors ranging from socioeconomic, environmental, and biological to individual lifestyle factors contribute to obesity. There is, however, sufficient evidence that consumption of high-calorie, energy-dense foods and beverages and insufficient physical activity play a significant role (274)Trust for America’s Health. State of Obesity 2021: Better Policies for a Healthier America. [updated November 5, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. To achieve and maintain good health, USDA and HHS, in Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, recommend that individuals follow a healthy dietary pattern at every stage of life (298)U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. [updated December 2020, cited 2022 April 22].. According to the guidelines, all individuals should fulfill their nutritional needs by consuming nutrient-dense food and beverages including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, lean meat, eggs, seafood, beans, legumes, nuts, and vegetable oil, and limit foods and beverages that are high in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, as well as alcoholic beverages (298)U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. [updated December 2020, cited 2022 April 22]..

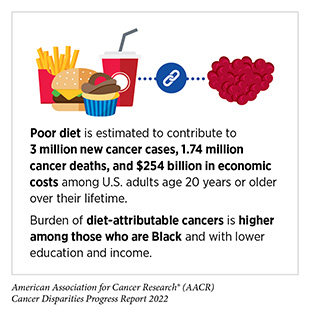

In the United States, more than 5 percent of all newly diagnosed cancer cases among adults are attributable to eating a poor diet (300)Zhang FF, Cudhea F, Shan Z, Michaud DS, Imamura F, Eom H, et al. Preventable Cancer Burden Associated with Poor Diet in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectrum 2019;3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Research shows that daily intake of five servings of fruit and vegetables is associated with a 10 percent reduction in overall cancer mortality when compared to intake of two servings per day (301)Wang DD, Li Y, Bhupathiraju SN, Rosner BA, Sun Q, Giovannucci EL, et al. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Mortality. Circulation 2021;143:1642-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Higher intake of red meat is associated with increased risk, whereas higher intake of dietary fiber and whole grains is associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer incidence (121)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2021-2022. [updated January 12, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].(302)Veettil SK, Wong TY, Loo YS, Playdon MC, Lai NM, Giovannucci EL, et al. Role of Diet in Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Prospective Observational Studies. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2037341. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](303)Gurjao C, Zhong R, Haruki K, Li YY, Spurr LF, Lee-Six H, et al. Discovery and Features of an Alkylating Signature in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov 2021;11:2446-55. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations are at a higher risk of poor dietary habits. For example, consumption of whole grains is lower among Hispanic (11 percent) and Black (14 percent) adults compared to White (17 percent) and Asian (18 percent) adults (121)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2021-2022. [updated January 12, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].; federal guideline-concordant vegetable intake is lower among Black adults (seven percent) compared to White (10 percent) or Hispanic adults (11 percent)(304)Lee SH, Moore LV, Park S, Harris DM, Blanck HM. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations – United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:1-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is concerning that, according to a recent analysis, there was a greater increase in the consumption of unhealthy ultraprocessed foods between 1999 and 2018 among Black and Mexican American youths compared to White youths (305)Wang L, Martínez Steele E, Du M, Pomeranz JL, O’Connor LE, Herrick KA, et al. Trends in Consumption of Ultraprocessed Foods among US Youths Aged 2-19 Years, 1999-2018. JAMA 2021;326:519-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, while overall dietary patterns in the U.S. have improved over the past two decades, the progress has been uneven across different populations (121)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2021-2022. [updated January 12, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. As one example, according to a recent analysis, diet quality has improved over the past two decades for Black and White young adults (ages 18-39), while remaining the same for Mexican Americans. The data further indicate that even though individuals from all income levels experienced some improvement in diet quality, the disparity between low- and high-income groups increased considerably (306)Patetta MA, Pedraza LS, Popkin BM. Improvements in the Nutritional Quality of US Young Adults Based on Food Sources and Socioeconomic Status between 1989–1991 and 2011–2014. Nutrition Journal 2019;18:32. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are also regional differences in dietary patterns. For instance, consumption of recommended fruits and vegetables is lower in Puerto Rico compared to the continental U.S. (121)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2021-2022. [updated January 12, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Intensive efforts by all stakeholders are needed if we are to increase the number of people who consume a balanced diet such as that recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025.

A major barrier to a healthy diet is food insecurity, defined by the USDA as the lack of access by all people in a household at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. Many studies have found an association between food insecurity and excess body weight (274)Trust for America’s Health. State of Obesity 2021: Better Policies for a Healthier America. [updated November 5, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. It is concerning that the prevalence of food insecurity has increased from approximately nine percent to 18 percent between 2000 and 2016, and that racial and ethnic minorities and individuals living in poverty have significantly higher likelihood of living with food insecurity (310)Myers CA, Mire EF, Katzmarzyk PT. Trends in Adiposity and Food Insecurity among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2012767. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, low-income and racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods are often located in “food deserts,” lacking access to healthy food retail such as supermarkets, while having an overabundance of convenience stores with unhealthy, highly processed, and fast-food options (274)Trust for America’s Health. State of Obesity 2021: Better Policies for a Healthier America. [updated November 5, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].(311)Bower KM, Thorpe RJ, Jr., Rohde C, Gaskin DJ. The Intersection of Neighborhood Racial Segregation, Poverty, and Urbanicity and Its Impact on Food Store Availability in the United States. Prev Med 2014;58:33-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Higher food insecurity rates are associated with increased likelihood of late-stage cancer (312)Ojinnaka CO, Christ J, Bruening M. Is There a Relationship between County-Level Food Insecurity Rates and Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis? Nutr Cancer 2021:1-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is growing recognition that systemic inequities and social injustices contribute to food insecurity (313)Odoms-Young A, Bruce MA. Examining the Impact of Structural Racism on Food Insecurity: Implications for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities. Fam Community Health 2018;41 Suppl 2 Suppl, Food Insecurity and Obesity:s3-s6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is imperative that all sectors work together to identify evidence-based public policies and programs that address structural racism and discrimination and alleviate disparities in access to healthy food options. Public education to improve nutritional knowledge must be a key component of such policies considering recent observations that the association between greater access to grocery stores and increased fruit and vegetable consumption varies widely by race/ethnicity and that high educational attainment rather than high income or access to grocery stores has the strongest association with healthy eating behavior in racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods (314)Althoff T, Nilforoshan H, Hua J, Leskovec J. Large-Scale Diet Tracking Data Reveal Disparate Associations between Food Environment and Diet. Nature communications 2022;13:267. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

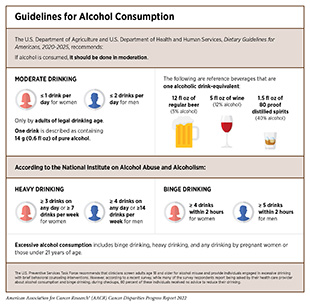

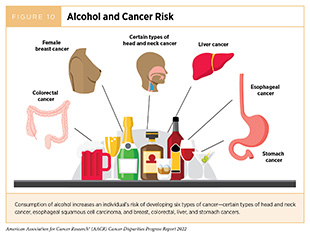

Alcohol consumption increases the risk for six different types of cancer (260)World Cancer Research Fund International. Diet, Activity and Cancer. [updated April 22, 2022, cited 2022 April 22]. (Figure 10), and emerging evidence suggests that there may be increased risks for additional cancer types (315)315.Papadimitriou N, Markozannes G, Kanellopoulou A, Critselis E, Alhardan S, Karafousia V, et al. An Umbrella Review of the Evidence Associating Diet and Cancer Risk at 11 Anatomical Sites. Nature communications 2021;12:4579. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Even modest use of alcohol may increase cancer risk, but the greatest risks are associated with excessive and/or long-term consumption (316)Hydes TJ, Burton R, Inskip H, Bellis MA, Sheron N. A Comparison of Gender-Linked Population Cancer Risks between Alcohol and Tobacco: How Many Cigarettes Are There in a Bottle of Wine? BMC Public Health 2019;19:316. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](317)LoConte NK, Brewster AM, Kaur JS, Merrill JK, Alberg AJ. Alcohol and Cancer: A Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:83-93. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](318)White AJ, DeRoo LA, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP. Lifetime Alcohol Intake, Binge Drinking Behaviors, and Breast Cancer Risk. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186:541-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](319)Xi B, Veeranki SP, Zhao M, Ma C, Yan Y, Mi J. Relationship of Alcohol Consumption to All-Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer-Related Mortality in U.S. Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:913-22. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (see sidebar on Guidelines for Alcohol Consumption). In the United States, alcohol consumption accounted for greater than 75,000 cancer cases and nearly 19,000 cancer deaths annually between 2013 and 2016 (320)Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Bandi P, Minihan AK, Stoklosa M, Drope J, et al. Proportion of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Alcohol Consumption by US State, 2013-2016. Cancer Epidemiol 2021;71:101893. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Consumption is higher among men with lower education and income compared to men who are college graduates and have higher income, as well as among certain SGM individuals compared to those who identify as straight (270)Bandi P, Minihan AK, Siegel RL, Islami F, Nargis N, Jemal A, et al. Updated Review of Major Cancer Risk Factors and Screening Test Use in the United States in 2018 and 2019, with a Focus on Smoking Cessation. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2021;30:1287-99. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Ongoing efforts focused on public education, evidence-based policy interventions such as regulating alcohol retail density, taxes, and prices, along with clinical strategies are being evaluated to reduce the consumption of alcohol and the burden of alcohol-related cancers. There is compelling evidence that racial and ethnic discrimination is associated with depression and social anxiety leading to hazardous drinking among Black and Hispanic adults (323)Buckner JD, Glover NI, Shepherd JM, Zvolensky MJ. Racial Discrimination and Hazardous Drinking among Black Drinkers: The Role of Social Anxiety in the Minority Stress Model. Subst Use Misuse 2022;57:256-62. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Prevention and treatment efforts must therefore consider the psychosocial and cultural factors that play a role in alcohol-related health problems in minorities and underserved populations.

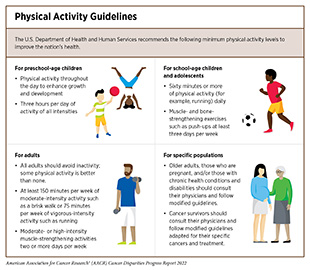

Three percent of overall cancer cases in the United States can be attributed to physical inactivity (210)Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and Number of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Engaging in recommended amounts of physical activity (see sidebar on Physical Activity Guidelines) can lower the risks for developing nine types of cancer (Figure 9), and there is emerging evidence that there may be risk reduction for even more cancer types (257)Matthews CE, Moore SC, Arem H, Cook MB, Trabert B, Håkansson N, et al. Amount and Intensity of Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Lower Cancer Risk. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:686-97. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](258)Patel AV, Friedenreich CM, Moore SC, Hayes SC, Silver JK, Campbell KL, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Cancer Prevention and Control. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019;51:2391-402. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](259)Moore SC, Lee IM, Weiderpass E, Campbell PT, Sampson JN, Kitahara CM, et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity with Risk of 26 Types of Cancer in 1.44 Million Adults. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:816-25. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Considering this evidence, it is concerning that more than a quarter of U.S. adults reported no physical activity in 2018 (270)Bandi P, Minihan AK, Siegel RL, Islami F, Nargis N, Jemal A, et al. Updated Review of Major Cancer Risk Factors and Screening Test Use in the United States in 2018 and 2019, with a Focus on Smoking Cessation. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2021;30:1287-99. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are also striking sociodemographic disparities among those who are physically active with a higher prevalence of activity recorded among adults who are White, have a graduate level education, higher income, and private health insurance (13)Islami F, Guerra CE, Minihan A, Yabroff KR, Fedewa SA, Sloan K, et al. American Cancer Society’s Report on the Status of Cancer Disparities in the United States, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:112-43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Living in low-income neighborhoods, which are more likely to lack safe and affordable options for physical exercise, such as gyms, biking and hiking trails, and biking and walking paths, contributes to disparities in the burden of obesity-related diseases in minorities and other underserved populations. Studies have shown that living in neighborhoods that are perceived to be safe and have attributes of walkability is associated with higher levels of physical activity among low-income and racial and ethnic minority populations (324)Shams-White MM, D’Angelo H, Perez LG, Dwyer LA, Stinchcomb DG, Oh AY. A National Examination of Neighborhood Socio-Economic Disparities in Built Environment Correlates of Youth Physical Activity. Prev Med Rep 2021;22:101358. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](325)Heredia NI, Fernandez ME, Durand CP, Kohl Iii HW, Ranjit N, van den Berg AE. Factors Associated with Use of Recreational Facilities and Physical Activity among Low-Income Latino Adults. J Immigr Minor Health 2020;22:555-62. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is imperative that health care professionals and policy makers work in concert to increase awareness of the benefits of physical activity and support programs and policies that facilitate an active lifestyle for all individuals in the United States.

It is equally important to include racially, ethnically, and geographically diverse populations in clinical trials on cancer prevention. Identifying social, cultural, behavioral, technological, and health care-related factors that encourage adherence to an active lifestyle in minorities and other medically underserved populations is critical to achieving health equity in cancer and other chronic diseases. In this regard, recent clinical trials provide valuable insights into strategies that may promote healthy behaviors in underserved populations as observed in rural Hispanic women in the state of Washington, residents in Alabama’s rural Black Belt region, and Hispanic adults along the Texas/Mexico border, among others (327)327.Levy DT, Meza R, Yuan Z, Li Y, Cadham C, Sanchez-Romero LM, et al. Public Health Impact of a US Ban on Menthol in Cigarettes and Cigars: A Simulation Study. Tobacco Control 2021:tobaccocontrol-2021-056604. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](328)Thirumalai M, Brown N, Niranjan S, Townsend SN, Powell MA, Neal W, et al. An Interactive Voice Response System to Increase Physical Activity and Prevent Cancer in the Rural Alabama Black Belt: Design and Usability Study. JMIR Hum Factors 2022;9:e29494. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](329)Heredia NI, Lee M, Reininger BM. Hispanic Adults’ Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Profiles: Examining Existing Data to Drive Prospective Research. J Public Health (Oxf) 2020;42:e120-e5. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The data from these trials identify positive influences on physical activity such as emotional and social support from promotoras (community health workers) or a romantic partner as well as technologies such as the interactive voice response system (327)327.Levy DT, Meza R, Yuan Z, Li Y, Cadham C, Sanchez-Romero LM, et al. Public Health Impact of a US Ban on Menthol in Cigarettes and Cigars: A Simulation Study. Tobacco Control 2021:tobaccocontrol-2021-056604. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](328)Thirumalai M, Brown N, Niranjan S, Townsend SN, Powell MA, Neal W, et al. An Interactive Voice Response System to Increase Physical Activity and Prevent Cancer in the Rural Alabama Black Belt: Design and Usability Study. JMIR Hum Factors 2022;9:e29494. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](330)Hornbuckle LM, Rauer A, Winters-Stone KM, Springer C, Jones CS, Toth LP. Better Together? A Pilot Study of Romantic Partner Influence on Exercise Adherence and Cardiometabolic Risk in African-American Couples. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2021;8:1492-504. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

UV Exposure

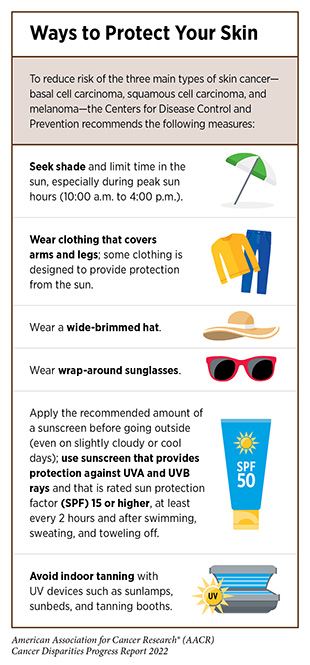

Exposure to UV radiation from the sun or indoor tanning devices poses a serious threat for the development of all three main types of skin cancer—basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma, which is the deadliest form of skin cancer. Thus, one of the most effective ways a person can reduce the risk of skin cancer is by practicing sun-safe habits and not using UV indoor tanning devices (see sidebar on Ways to Protect Your Skin).

Overall, exposure to UV light accounts for 4-6 percent of all cancers and is responsible for 95 percent of skin melanomas (210)Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and Number of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Disparities have been reported in the level of knowledge about the dangers of sun exposure and importance of using sunscreen, with Black and Hispanic individuals having less knowledge and being less likely to use sunscreen than White individuals (331)Cheng CE, Irwin B, Mauriello D, Hemminger L, Pappert A, Kimball AB. Health Disparities among Different Ethnic and Racial Middle and High School Students in Sun Exposure Beliefs and Knowledge. J Adolesc Health 2010;47:106-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](332)Summers P, Bena J, Arrigain S, Alexis AF, Cooper K, Bordeaux JS. Sunscreen Use: Non-Hispanic Blacks Compared with Other Racial and/or Ethnic Groups. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:863-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent survey indicated that greater than 80 percent of Native Americans report experiencing sunburns, while only 11 percent and 36 percent regularly use sunscreen on their bodies and faces, respectively (333)Maarouf M, Zullo SW, DeCapite T, Shi VY. Skin Cancer Epidemiology and Sun Protection Behaviors among Native Americans. J Drugs Dermatol 2019;18:420-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study showed that only six percent of Black and 24 percent of Hispanic fifth graders reported using sunscreens compared to 45 percent of their NHW counterparts (334)Correnti CM, Klein DJ, Elliott MN, Veledar E, Saraiya M, Chien AT, et al. Racial Disparities in Fifth-Grade Sun Protection: Evidence from the Healthy Passages Study. Pediatric Dermatology 2018;35:588-96. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These data are particularly concerning because sunburns—clear indicators of overexposure to UV radiation—during childhood pose one of the greatest risks for developing skin cancer later in life (335)Dennis LK, Vanbeek MJ, Beane Freeman LE, Smith BJ, Dawson DV, Coughlin JA. Sunburns and Risk of Cutaneous Melanoma: Does Age Matter? A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Ann Epidemiol 2008;18:614-27. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Recent studies show that sun safety interventions, such as those being evaluated in school settings and utilizing ethnically and racially tailored lessons on protective behaviors from trained health educators, can improve risk reducing behavior among children from diverse backgrounds (336)Miller KA, Huh J, Piombo SE, Richardson JL, Harris SC, Peng DH, et al. Sun Protection Changes among Diverse Elementary Schoolchildren Participating in a Sun Safety Intervention: A Latent Transition Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Preventive Medicine 2021;149:106601. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The level of knowledge about skin cancer risks among Black and Hispanic populations is influenced by the level of education (337)Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, Elmets C. Skin Cancer Risk Perceptions: A Comparison across Ethnicity, Age, Education, Gender, and Income. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66:771-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Overall, the disparity in skin cancer preventive behavior among these populations is of public health concern because Black and Hispanic people tend to be diagnosed at more advanced stages despite having a lower incidence of skin cancer (338)Culp MB, Lunsford NB. Melanoma among Non-Hispanic Black Americans. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:E79. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](339)Perez MI. Skin Cancer in Hispanics in the United States. J Drugs Dermatol 2019;18:s117-20. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are distinct characteristics of skin cancers in racial and ethnic minorities, e.g., places on the body where skin cancers tend to occur are often in less sun-exposed areas, making early detection more difficult (338)Culp MB, Lunsford NB. Melanoma among Non-Hispanic Black Americans. Prev Chronic Dis 2019;16:E79. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](339)Perez MI. Skin Cancer in Hispanics in the United States. J Drugs Dermatol 2019;18:s117-20. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. More research is needed to understand the association between UV exposure and the risk of melanoma as well as novel risk factors for skin cancer in racial and ethnic minorities (340)Davis DS, Robinson C, Callender VD. Skin Cancer in Women of Color: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestations. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology 2021;7:127-34. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](341)Lopes FCPS, Sleiman MG, Sebastian K, Bogucka R, Jacobs EA, Adamson AS. Uv Exposure and the Risk of Cutaneous Melanoma in Skin of Color: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatology 2021;157:213-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Data from such investigations will help identify and implement more effective interventions to reduce the burden of skin cancers among racial and ethnic minorities.

Use of indoor UV tanning devices increases a person’s risk for melanoma. Sexual minority men have been shown to have increased rates of indoor tanning compared with heterosexual men indicating that they may be at higher risk for skin cancer due to differential risk behaviors (342)Mansh M, Arron ST. Indoor Tanning and Melanoma: Are Gay and Bisexual Men More at Risk? Melanoma Manag 2016;3:89-92. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Laws prohibiting tanning can be effective in reducing tanning practice and may reduce the incidence of future melanoma cases (343)Stapleton JL, Hrywna M, Coups EJ, Delnevo C, Heckman CJ, Xu B. Prevalence and Location of Indoor Tanning among High School Students in New Jersey 5 Years after the Enactment of Youth Access Restrictions. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:1223-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](344)Eskander A, Marqueen KE, Edwards HA, Joshua AM, Petrella TM, de Almeida JR, et al. To Ban or Not to Ban Tanning Bed Use for Minors: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis from Multiple Us Perspectives for Invasive Melanoma. Cancer 2021;127:2333-41. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, as of January 1, 2021, in the U.S., only 20 states and the District of Columbia have laws prohibiting tanning for minors (under the age of 18)(121)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2021-2022. [updated January 12, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. It is vital that all stakeholders in public health continue to work together to develop and implement more effective policy changes and public education campaigns to reduce indoor tanning practice, especially among high-risk populations.

Infectious Agents

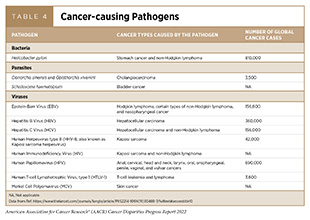

Persistent infection with several pathogens—disease causing bacteria, viruses, and parasites—increases a person’s risk for several types of cancer (see Table 4). Globally, an estimated 13 percent of all cancer cases in 2018 were attributable to pathogenic infections, with more than 90 percent of these cases attributable to four pathogens: HPV, HBV, HCV, and Helicobacter pylori (345)de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J, Clifford GM. Global Burden of Cancer Attributable to Infections in 2018: A Worldwide Incidence Analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e180-e90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](346)Hong CY, Sinn DH, Kang D, Paik SW, Guallar E, Cho J, et al. Incidence of Extrahepatic Cancers among Individuals with Chronic Hepatitis B or C Virus Infection: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J Viral Hepat 2020;27:896-903. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In the United States, about three percent of all cancer cases are attributable to infection with pathogens (210)Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and Number of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Individuals can significantly lower their risks by protecting themselves from the infection or by seeking treatment, if available, to eliminate an infection (see sidebar on Preventing or Eliminating Infection with the Four Main Cancer-causing Pathogens). It is important to note that even though strategies to eliminate, treat, or prevent infection with Helicobacter pylori, HBV, HCV, and HPV can significantly lower an individual’s risks for developing cancers, these strategies are not effective at treating infection-related cancers once they develop.

Helicobacter pylori is a type of bacterium that has been shown to cause gastric cancer. Among U.S. adults, H. pylori prevalence is two to three times higher among Mexican American and Black persons compared to White persons (122)Bandera EV, Alfano CM, Qin B, Kang DW, Friel CP, Dieli-Conwright CM. Harnessing Nutrition and Physical Activity for Breast Cancer Prevention and Control to Reduce Racial/Ethnic Cancer Health Disparities. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2021;41:1-17. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], which may contribute to the higher rates of gastric cancer in these populations. Prevalence is also greater among non-U.S.-born individuals and varies by Hispanic/Latino background (46)Tsang SH, Avilés-Santa ML, Abnet CC, Brito MO, Daviglus ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Seroprevalence and Determinants of Helicobacter Pylori Infection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022;20:e438-e51. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Declining rates of H. pylori infection have been reported recently, which may be due in part to improved access to health care and healthier living (347)Luo G, Zhang Y, Guo P, Wang L, Huang Y, Li K. Global Patterns and Trends in Stomach Cancer Incidence: Age, Period and Birth Cohort Analysis. International journal of cancer 2017;141:1333-44. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Chronic infection with HBV and HCV can cause liver cancer and is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for additional malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The rates of HBV infection decreased among all racial and ethnic groups during 2004 and 2014 with a steeper decline observed among minorities compared to White people (348)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. [updated May 19, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. Unfortunately, after decades of progress, the number of new HBV infections is now rising among adults despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine. HBV infection is also higher among certain populations who emigrated from outside the U.S. As one example, the higher burden of liver cancer due to chronic HBV infection among Asian individuals can be attributed to high HBV prevalence in the country of origin and recent immigration (22)Wong RJ, Brosgart CL, Welch S, Block T, Chen M, Cohen C, et al. An Updated Assessment of Chronic Hepatitis B Prevalence among Foreign-Born Persons Living in the United States. Hepatology 2021;74:607-26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. CDC recently recommended that all adults ages 19-59 years receive a vaccination for HBV (349)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Universal Hepatitis B Vaccination in Adults Aged 19–59 Years: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. [updated April 15, 2022, cited 2022 April 22].. Additionally, CDC recommended that adults age 60 years and older without known risk factors for HBV also get vaccinated. Current evidence suggests significant gaps in the perception, evaluation, and treatment of HBV especially among racial and ethnic minorities, highlighting the need for community-based, culturally appropriate interventions to mitigate the disproportionate impact of the virus in these populations (350)Ye Q, Kam LY, Yeo YH, Dang N, Huang DQ, Cheung R, et al. Substantial Gaps in Evaluation and Treatment of Patients with Hepatitis B in the US. Journal of Hepatology 2022;76:63-74. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](351)Jones P, Soler J, Solle NS, Martin P, Kobetz E. A Mixed-Methods Approach to Understanding Perceptions of Hepatitis B and Hepatocellular Carcinoma among Ethnically Diverse Black Communities in South Florida. Cancer Causes Control 2020;31:1079-91. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Acute infection with HCV is often asymptomatic but more than half of these cases progress to chronic infection. Therefore, it is extremely concerning that the rate of reported acute HCV cases in the United States increased by 89 percent between 2014 and 2019 with most cases occurring among individuals ages 20–39 years (348)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. [updated May 19, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. There are disparities in the rates of acute HCV infection among racial and ethnic groups with the highest rate of 3.6 cases per 100,000 reported among AI/AN persons. Liver cancer incidence and mortality rates are also higher among AI/ AN populations compared to White people (see Table 1; and American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) Population, p. 21). Among AI/AN, HCV infections occur earlier than in other racial and ethnic groups and HCV-related deaths are double the national rate (352)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatits Surveillance United States, 2016. [updated January 1, 2016, cited 2022 April 22].. To reduce the burden of HCV, the Indian Health Service (IHS) recommends universal screening of all AI/AN adults (353)Indian Health Service. Hepatitis C: Universal Screening and Treatment. [updated May 16, 2019, cited 2022 April 22].. While rates of infection among Black and Hispanic persons are lower compared to White persons, Black and Hispanic populations have recorded the greatest increases in infection between 2010 and 2019 (348)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report. [updated May 19, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. To eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat, HHS recently released the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021–2025) (354)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021-2025). [updated January 4, 2021, cited 2022 April 22].. The primary goals listed in the report are to prevent new infections, improve hepatitis-related health outcomes for infected individuals, reduce disparities and health inequities related to hepatitis, improve surveillance of viral hepatitis, and bring together all relevant stakeholders in coordinating efforts to address the hepatitis epidemic.