In this section you will learn:

- The goal of screening is to find precancer or cancer at the earliest possible time in development because this increases the chance for successful treatment.

- There are four types of cancer (breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate) for which screening tests have been used to screen large segments of the U.S. population who are at average risk of developing the cancer being screened for.

- Many people for whom cancer screening is recommended do not get screened, including a disproportionate number of individuals who are part of U.S. population groups that experience cancer health disparities such as racial and ethnic minority groups and underserved populations.

- Research is identifying culturally tailored strategies to increase cancer screening awareness, access, and uptake among different population groups for whom screening is recommended.

How Can We Screen for Cancer and What Are the Screening Recommendations?

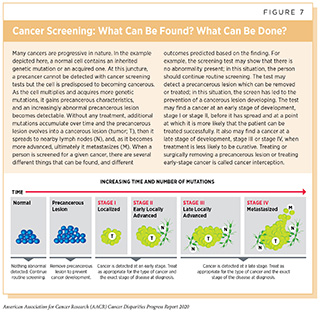

Screening for cancer means checking for precancerous lesions or cancer in people who have no signs or symptoms of the cancer for which they are being checked. The aim is to find an abnormality at the earliest possible time in cancer development. If a cancer screening test shows a precancerous lesion is present, it can be treated or surgically removed before becoming cancer (see Figure 7). If a test finds a cancer at an early stage of development, stage I or stage II, before it has spread, it is more likely that the patient can be treated successfully; for example patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer that is confined to the colon or rectum have a 5-year relative survival rate of 90 percent, while those diagnosed with colorectal cancer that has metastasized have a 5-year relative survival rate of 14 percent (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Screening for cancer can be done in various ways, including by using imaging technologies to look for abnormalities inside the body, and by collecting tissue or fluid samples and then analyzing them for abnormalities characteristic of the cancer being screened for. The tests used to screen for the five cancers for which screening is most commonly conducted are highlighted in “How Can We Screen for Cancer?“.

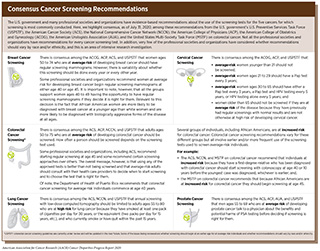

Screening for cancer has many benefits, but it also has the potential to cause unintended harms (see sidebar on Cancer Screening). Therefore, cancer screening is not recommended for everyone. The U.S. government and many professional societies and organizations convene panels of experts to carefully evaluate data regarding the benefits and potential harms of cancer screening tests. Although each panel creates its own evidence-based recommendations about the use of these tests, there is more consensus among recommendations than disagreement (see sidebar on Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations).

Cancer Screening among U.S. Racial and Ethnic Groups

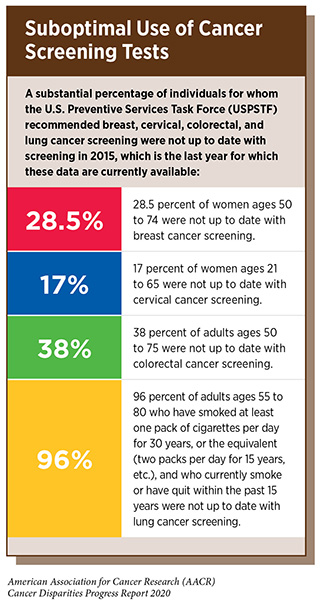

Even though the benefits of cancer screening outweigh the potential risks for defined groups of individuals (see sidebar on Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations), many people for whom screening is recommended do not get screened (18)White A, Thompson TD, White MC, Sabatino SA, Moor J de, Doria-Rose P V., et al. Cancer screening test use — United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2017;66:201–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(220)Jemal A, Fedewa SA, E B. Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose Computed Tomography in the United States—2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 3];63:107–17.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see sidebar on Suboptimal Use of Cancer Screening Tests). Individuals who are not up to date with cancer screening recommendations are disproportionately found among segments of the U.S. population that experience cancer health disparities, including racial and ethnic minority groups (see Table 7).

Breast Cancer Screening

Even though the breast cancer screening rate—as defined by the percentage of women ages 50 to 74 who report having had a screening mammogram in the past 2 years—for African American women is very similar to that for white women, 9 percent of African American women are diagnosed with breast cancer when the disease is at an advanced stage compared with 5 percent of white women (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The disparity in advanced stage of diagnosis is one factor contributing to the striking disparity in the breast cancer death rates for African American and white women, which are 27.3 per 100,000 and 19.6 per 100,000, respectively (see Table 1).

The disparity in advanced stage of diagnosis between African American and white women despite similar breast cancer screening rates is attributed to a complex interplay among various determinants of health related to socioeconomic status and access to quality cancer care (see Why Do Cancer Health Disparities Exist?). The contributing social, clinical, and environmental factors include African American women overestimating screening mammogram utilization, having longer intervals between screening mammograms, experiencing less timely follow-up of abnormal results, being screened at lower resourced and nonaccredited facilities, and having reduced likelihood of receiving follow-up care at a comprehensive care center (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].(221)Warnecke RB, Campbell RT, Vijayasiri G, Barrett RE, Rauscher GH. Multilevel Examination of Health Disparity: The Role of Policy Implementation in Neighborhood Context, in Patient Resources, and in Healthcare Facilities on Later Stage of Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];28:59–66.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(222)Mann L, Foley KL, Tanner AE, Sun CJ, Rhodes SD. Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Among US Hispanics/Latinas: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:374–87.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Cervical Cancer Screening

Low rates of cervical cancer screening among Hispanics are a major factor contributing to the higher cervical cancer incidence rate experienced by this ethnic minority group compared with whites (see Table 2 and Table 7, respectively). The disparity in cervical cancer screening rates between Hispanic and white women has been attributed to many social, clinical, cultural, psychological, and environmental factors, including a lack of health insurance, low levels of awareness about screening, distrust of the health care system, and cultural beliefs about sexual health (222)Mann L, Foley KL, Tanner AE, Sun CJ, Rhodes SD. Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Among US Hispanics/Latinas: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:374–87.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Even though cervical cancer screening rates are similar for African American and white women, African American women have a higher cervical cancer incidence rate compared with white women (see Table 1 and Table 7, respectively). The reasons for this are not very clear but include social, clinical, and environmental factors that affect socioeconomic status and access to quality cancer care (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. African American women are also more likely to be diagnosed with more advanced stage cervical cancer compared with white women, which may be because of differences in the quality of the facility at which the screening is conducted and timeliness of follow-up of abnormal results (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Colorectal Cancer Screening

Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening rates are particularly striking for colorectal cancer (18)White A, Thompson TD, White MC, Sabatino SA, Moor J de, Doria-Rose P V., et al. Cancer screening test use — United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2017;66:201–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(223)American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Cancer Disparities: A Chartbook. Strategies [Internet]. 2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Table 7). Disparities in colorectal cancer screening rates contribute substantially to disparities in colorectal cancer outcomes, with one study estimating that differences in colorectal cancer screening rates are responsible for 19 percent of the disparity between the colorectal cancer death rates for African Americans and whites (19)Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Jemal A. Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 11];21:728–36.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Until recently, it was widely recommended that colorectal cancer screening for individuals at average risk for the disease begin at age 50 (see sidebar on Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations). After evidence emerged showing that the proportion of colorectal cancers diagnosed before age 50 was almost double for African Americans compared with whites (10.6 percent compared with 5.5 percent), the United States Multi-Society Task Force updated its colorectal cancer screening recommendations to advise that African Americans begin screening at age 45 (224)Rex DK, Boland RC, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T, et al. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Recommendations for Physicians and Patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 17];112:1016–30.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition, the Department of Health of Puerto Rico changed its recommendation in 2015 to advise that colorectal cancer screening for average risk individuals begin at age 40 (225)OA 334-PARA ORDENAR LA PRUEBA DE DETECCION DE SANGRE OCULTA A REALIZARSE COMO REQUISITO ANUAL.pdf.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This change was made after it was shown that Hispanics living in Puerto Rico had a higher colorectal cancer incidence rate than Hispanics in the continental United States and Hawaii and that the U.S. colorectal cancer incidence rate among adults younger than 50 was increasing sharply (226)O’Neil ME, Henley SJ, Singh SD, Wilson RJ, Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Ríos NP, et al. Invasive cancer incidence – Puerto Rico, 2007-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 18];64:389–93.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(227)American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2017-2019. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. 2019;[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

There are many social, clinical, cultural, psychological, and environmental factors that contribute to disparities in colorectal cancer screening among racial and ethnic minority groups. For African Americans, research has shown that poor knowledge of colorectal cancer risk, low perception of the benefits of screening, perceived invasiveness of colonoscopy, fear of pain, financial concerns, lack of insurance and access to care, and not having received a recommendation to undergo screening from a health care provider all contribute to low levels of colorectal cancer screening (228)May FP, Whitman CB, Varlyguina K, Bromley EG, Spiegel BMR. Addressing Low Colorectal Cancer Screening in African Americans: Using Focus Groups to Inform the Development of Effective Interventions. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];31:567–74.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(229)Bromley EG, May FP, Federer L, Spiegel BMR, van Oijen MGH. Explaining persistent under-use of colonoscopic cancer screening in African Americans: a systematic review. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];71:40–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For Hispanics, cultural factors such as distrust in health care and having English as a second language have been shown to be particularly important drivers of disparities in colorectal cancer screening (230)Hong Y-R, Tauscher J, Cardel M. Distrust in health care and cultural factors are associated with uptake of colorectal cancer screening in Hispanic and Asian Americans. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];124:335–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(231)Emmons K, Puleo E, McNeill LH, Bennett G, Chan S, Syngal S. Colorectal cancer screening awareness and intentions among low income, sociodemographically diverse adults under age 50. Cancer Causes Control [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 17];19:1031–41.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Lung Cancer Screening

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States (34)American Cancer Society. Facts & Figures 2019. Am Cancer Soc Atlanta, Ga. 2019;[cited 2020 Jul 15].. It is estimated that the lung cancer death rate could be reduced by 20 percent among all individuals eligible for lung cancer screening based on U.S. government recommendations—individuals ages 55 to 80 who still smoke or have quit within the last 15 years—if they were all to be screened (332)Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-Based Assessment of Cancer Survivors’ Financial Burden and Quality of Life: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Oncol Pract [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];11:145–50.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Despite the benefits of lung cancer screening, it is estimated that only 3.9 percent of the 6.8 million individuals eligible for lung cancer screening in 2015 underwent screening (220)Jemal A, Fedewa SA, E B. Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose Computed Tomography in the United States—2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 3];63:107–17.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. With such low rates of screening it is hard to determine whether there are racial and ethnic disparities. Therefore, the researchers considered just two groups, whites and nonwhites, and found that lung cancer screening rates for the two groups were 4.1 percent and 2.1 percent, respectively (220)Jemal A, Fedewa SA, E B. Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose Computed Tomography in the United States—2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Feb 3];63:107–17.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

One reason for low lung cancer screening rates is that just 4.4 percent of whites and 5 percent of African Americans report that a physician has discussed screening with them (233)Huo J, Hong Y-R, Bian J, Guo Y, Wilkie DJ, Mainous AG. Low Rates of Patient-Reported Physician–Patient Discussion about Lung Cancer Screening among Current Smokers: Data from Health Information National Trends Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 20];28:963–73.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Identifying strategies to increase lung cancer screening rates among all eligible individuals, including by improving physician–patient discussion, is a priority for all stakeholders in the cancer research community.

It is particularly important to identify ways to increase screening among African American men because they are 15 percent more likely to develop lung cancer compared with white men and 18 percent more likely to die from the disease (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This increased risk exists even though African American men who are smokers smoke fewer cigarettes each day compared with white men who are smokers, and begin smoking at an older age (234)Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, et al. Ethnic and Racial Differences in the Smoking-Related Risk of Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet]. Massachusetts Medical Society ; 2006 [cited 2019 Dec 17];354:333–42.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The increased risk of lung cancer among African American men despite lower pack years of smoking has led to the suggestion that lung cancer screening recommendations may need to be tailored for individuals in different racial and ethnic groups (235)Tanner NT, Gebregziabher M, Hughes Halbert C, Payne E, Egede LE, Silvestri GA. Racial Differences in Outcomes within the National Lung Screening Trial. Implications for Widespread Implementation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Jan 22];192:200–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Of relevance to this suggestion is the fact that the benefits of lung cancer screening were established in a clinical trial in which 90.9 percent of the participants were white and just 4.5 percent were African Americans (237)Team TNLSTR. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med [Internet]. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 17];365:395–409.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Prostate Cancer Screening

The U.S. government and many professional societies and organizations recommend that men ages 55 to 69 who are at average risk of developing prostate cancer talk to a physician about the benefits and potential harms of screening before deciding if it is right for them. Some professional societies and organizations recommend that African American men like Colonel Gary Steele begin this conversation at age 45 because the prostate cancer incidence rate is dramatically higher for African American men compared with men of any other race or ethnicity, which means that they are at increased risk for developing the disease (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Even though African American men have a higher risk for prostate cancer compared with white men, there is a striking disparity in prostate cancer screening rates (see Table 7). There is also a marked disparity in prostate cancer screening rates between Hispanic and white men, which may contribute to the fact that Hispanic men are more likely to be diagnosed (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. with advanced stage prostate cancer compared with white men (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Of note, the disparity in prostate cancer screening between African American and white men exists even though African American men are more likely to report having been informed about prostate cancer screening than white men (238)Cooper DL, Rollins L, Slocumb T, Rivers BM. Are Men Making Informed Decisions According to the Prostate-Specific Antigen Test Guidelines? Analysis of the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Mens Health [Internet]. SAGE Publications; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];13:1557988319834843.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Understanding the reasons for the low rates of prostate cancer screening among African American men informed about screening is vital if disparities in the burden of prostate cancer are to be eliminated. It will also be critical to determine whether there are differences in the benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening for men of different races and ethnicities, information that is currently lacking (239)Miller EA, Pinsky PF, Black A, Andriole GL, Pierre-Victor D. Secondary prostate cancer screening outcomes by race in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Screening Trial. Prostate [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];78:830–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Increasing Cancer Screening Rates among Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Identifying strategies to increase cancer screening awareness, access, and uptake among those for whom screening is recommended is an important step toward achieving health equity. Strategies for increasing cancer screening rates among racial and ethnic minorities including increasing health literacy and awareness of cancer and cancer screening through culturally-tailored community education and through the sharing of information by racial and ethnic minority patient advocates like Tristana Vásquez. It is also important to ensure that everyone has access to high-quality clinical care. In addition, more targeted strategies for each type of screening and for each racial and ethnic minority group need to be developed, and this is an area of active research investigation. Some of the approaches being assessed are described here.

Mobile mammography units are one approach showing promise for increasing breast cancer screening rates among medically underserved populations, including racial and ethnic minorities (240)Vang S, Margolies LR, Jandorf L. Mobile Mammography Participation Among Medically Underserved Women: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];15:180291.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(241)Stanley E, Lewis MC, Irshad A, Ackerman S, Collins H, Pavic D, et al. Effectiveness of a Mobile Mammography Program. Am J Roentgenol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 17];209:1426–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Mobile mammography units help eliminate transportation barriers to screening and, in some instances, screening is provided for free. However, some studies have found that patient retention and patient follow-up after an abnormal screening mammogram result are lower among women screened at mobile mammography units compared with those screened in fixed facilities, highlighting that greater patient education and patient navigation are needed if the mobile units are to improve their effectiveness at addressing disparities in breast cancer outcomes (240)Vang S, Margolies LR, Jandorf L. Mobile Mammography Participation Among Medically Underserved Women: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];15:180291.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Numerous studies have shown that colorectal cancer screening rates can be significantly increased for all racial and ethnic groups by actively reaching out to adults not up to date with screening, either by mailing them information about colorectal cancer risk and a stool test or by implementing patient navigation programs that provide individualized assistance to help patients overcome personal and health care system barriers, and to facilitate understanding and timely access to screening (240)Vang S, Margolies LR, Jandorf L. Mobile Mammography Participation Among Medically Underserved Women: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];15:180291.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(243)Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, Gupta S, Wheeler SB, Coker-Schwimmer M, et al. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];178:1645–58.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(244)Christy SM, Davis SN, Williams KR, Zhao X, Govindaraju SK, Quinn GP, et al. A community-based trial of educational interventions with fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer screening uptake among blacks in community settings. Cancer [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];122:3288–96.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(245)Goldman SN, Liss DT, Brown T, Lee JY, Buchanan DR, Balsley K, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Multifaceted Outreach to Initiate Colorectal Cancer Screening in Community Health Centers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. Springer; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:1178–84.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

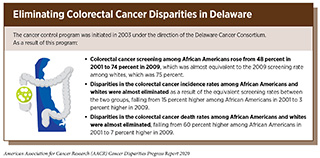

One example of how effective patient navigation can be at reducing disparities in colorectal cancer screening and outcomes is the cancer control program that was established in 2003 in Delaware (246)Grubbs SS, Polite BN, Carney J, Jr, Bowser W, Rogers J, et al. Eliminating Racial Disparities in Colorectal Cancer in the Real World: It Took a Village. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 17];31:1928.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. A key component of this program was increasing colorectal cancer screening among racial and ethnic minorities through patient navigation. Through this program, colorectal cancer screening rates for African Americans rose from 48 percent in 2001 to 74 percent in 2009, which was equivalent to the screening rate for whites. During that time, disparities in the colorectal cancer incidence and death rates between African Americans and whites were almost eliminated (see sidebar on Eliminating Colorectal Cancer Disparities in Delaware). Unfortunately, substantial financial, infrastructure, and social challenges may prevent implementation of identical programs nationwide. As a result, other approaches to increasing colorectal cancer screening among racial and ethnic minorities are needed, with one focus group showing that culturally specific information and dissemination of colorectal cancer screening education through commercials and billboards could be effective for African Americans (228)May FP, Whitman CB, Varlyguina K, Bromley EG, Spiegel BMR. Addressing Low Colorectal Cancer Screening in African Americans: Using Focus Groups to Inform the Development of Effective Interventions. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];31:567–74.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The most effective approaches to increasing cervical cancer screening among Hispanics involve culturally-tailored interventions that address low levels of health literacy and issues rooted in cultural beliefs and fears (247)Ochoa CY, Murphy ST, Frank LB, Baezconde-Garbanati LA. Using a Culturally Tailored Narrative to Increase Cervical Cancer Detection Among Spanish-Speaking Mexican-American Women. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. J Cancer Educ; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 22];[cited 2020 Jul 15].(248)Thompson B, Carosso EA, Jhingan E, Wang L, Holte SE, Byrd TL, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to increase cervical cancer screening among rural Latinas. Cancer [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 22];123:666–74.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Using community-based participatory research approaches and lay health advisors are ways to ensure that interventions are culturally sensitive (222)Mann L, Foley KL, Tanner AE, Sun CJ, Rhodes SD. Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Among US Hispanics/Latinas: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:374–87.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(248)Thompson B, Carosso EA, Jhingan E, Wang L, Holte SE, Byrd TL, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to increase cervical cancer screening among rural Latinas. Cancer [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 22];123:666–74.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Lay health advisors are community members who provide help in many different ways, depending on the program that has been developed. For example, some serve as community role models by participating in mass media campaign messages; some distribute culturally-tailored intervention materials such as community bulletins, flyers, educational pamphlets, and information about local providers and screening resources; some coordinate support such as childcare and transportation for women who need screening; and some serve as navigators and facilitators for women at screening facilities (222)Mann L, Foley KL, Tanner AE, Sun CJ, Rhodes SD. Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Among US Hispanics/Latinas: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J Cancer Educ [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:374–87.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Culturally-tailored interventions have also been shown to increase cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese Americans (249)Ma GX, Fang C, Tan Y, Feng Z, Ge S, Nguyen C. Increasing Cervical Cancer Screening Among Vietnamese Americans: A Community-Based Intervention Trial. J Health Care Poor Underserved [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Jan 22];26:36–52.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Increasing cancer screening rates alone will not eliminate cancer health disparities. We need to ensure that individuals whose screening tests show an abnormality receive follow-up testing and care in a timely manner. Delayed follow-up can result in a later stage diagnosis and, therefore, a reduced chance that the patient can be treated successfully. Individuals who delay or who never return for follow-up care after a cancer screening test shows an abnormality are disproportionately found in the same population groups that experience disparities in other measures of cancer burden. For example, follow-up after cervical cancer screening detects an abnormality is lowest among women who are African American, who have low socioeconomic status, or who lack private health insurance (250)Benard VB, Lawson HW, Eheman CR, Anderson C, Helsel W. Adherence to Guidelines for Follow-up of Low-Grade Cytologic Abnormalities Among Medically Underserved Women. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2020 Jan 22];105:1323–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(251)Engelstad LP, Stewart SL, Nguyen BH, Bedeian KL, Rubin MM, Pasick RJ, et al. Abnormal Pap smear follow-up in a high-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2001 [cited 2020 Jan 22];10:1015–20.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..