The State of Cancer Health Disparities in 2020

In this section you will learn:

- Cancer health disparities are adverse differences in cancer burden between different population groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, individuals of low socioeconomic status, and members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community.

- Progress in reducing cancer health disparities is being made, as illustrated by the narrowing of the disparity in the overall cancer death rate for African Americans compared with whites from 33 percent higher in 1990 to 14 percent higher in 2016.

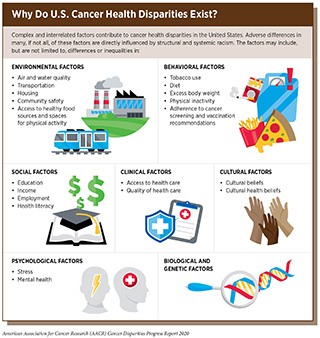

- Several complex and interrelated factors contribute to cancer health disparities, including social, clinical, behavioral, cultural, environmental, and genetic and biological factors.

- The economic burden of health disparities, including cancer health disparities, is enormous.

- We can accelerate the pace of progress by enhancing collaboration among stakeholders committed to eliminating cancer health disparities.

Cancer is an enormous public health challenge in the United States and around the world. In the United States alone, it is projected that 1,806,590 new cases of cancer will be diagnosed in 2020 and that there will be 606,520 deaths from the disease (1). These numbers translate into 206 new cancer cases and 69 cancer deaths every hour of every day.

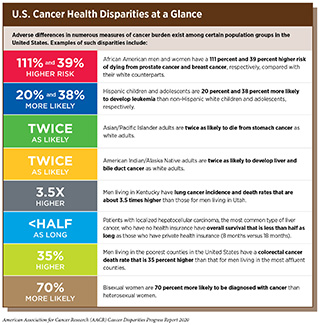

The grim reality is that the burden of cancer is not shouldered equally by all segments of the U.S. population (see sidebars on Which U.S. Population Groups Experience Cancer Health Disparities?, and U.S. Cancer Health Disparities at a Glance). Adverse differences in the burden of cancer that exist among certain population groups are referred to as cancer health disparities. The exact measures of cancer burden that are considered when discussing cancer health disparities can vary. Throughout this report, we use the National Cancer Institute (NCI) definition of cancer health disparities:

- Cancer health disparities are adverse differences between certain population groups in cancer measures such as number of new cases, number of deaths, cancer-related health complications, survivorship and quality of life after cancer treatment, screening rates, and stage at diagnosis (2)Cancer Health Disparities Definitions – National Cancer Institute [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jun 19].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

In this opening chapter of the inaugural AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report, we provide an overview of the current status of disparities in cancer incidence rates (the number of new individuals per 100,000 people in the population of interest diagnosed with cancer) and cancer death rates (the number of individuals per 100,000 people in the population of interest who die from cancer) in the United States with a focus on the disparities experienced by the major racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States—African Americans, Hispanics, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and American Indians/Alaska Natives (see sidebar on U.S. Racial and Ethnic Population Groups). Other chapters of the report highlight disparities in other measures of cancer burden with an emphasis on African Americans and Hispanics.

Identifying, quantifying, and understanding the causes of cancer health disparities is a vital step toward developing and implementing strategies to eliminate the disparities and achieve cancer health equity. According to the World Health Organization, health equity is the idea that everyone should have a fair opportunity to attain their full health potential regardless of demographic, social, economic or geographic strata (11)WHO | Equity. WHO [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 22];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Disparities in the Burden of Cancer among U.S. Racial and Ethnic Population Groups

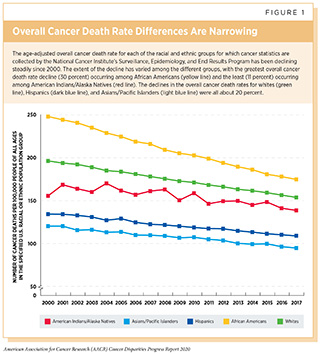

It has long been recognized that the burden of cancer, as measured by cancer incidence and death rates, is not equivalent among the different racial and ethnic groups in the United States. For example, when considering all cancers combined, African Americans have the highest cancer death rate followed by whites, American Indian/Alaska Natives, Hispanics, and Asian/Pacific Islanders (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Differences in the overall cancer death rate between racial and ethnic groups in the United States are less pronounced now than they were in the early 2000s (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Figure 1). For example, the disparity in the overall cancer death rate has narrowed from 33 percent higher for African Americans compared with whites in 1990 to 14 percent higher for African Americans in 2016. Even more encouragingly, the disparity in the overall cancer death rate between African Americans and whites has been nearly eliminated among men younger than 50 and women age 70 or older (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The reductions in the disparity in the overall cancer death rate occurred because the overall cancer death rate decreased more rapidly among African Americans than it did among whites during this period.

Despite the progress, the African American population still shoulders a disproportionately high burden of overall cancer mortality compared with other racial and ethnic groups. In addition, racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States experience striking disparities in incidence and death rates for various types of cancer.

Cancers with a Disproportionate Burden in African Americans

African Americans are the second-largest racial and ethnic minority group in the United States, comprising about 13 percent of the U.S. population (13)Bureau UC. National Population by Characteristics: 2010-2019. [cited 2020 Jan 22];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For more than four decades, African Americans have had higher overall cancer incidence and death rates than all other racial and ethnic groups in the United States. An estimated 202,260 African Americans were diagnosed with cancer and 75,030 died from the disease in 2019 alone (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

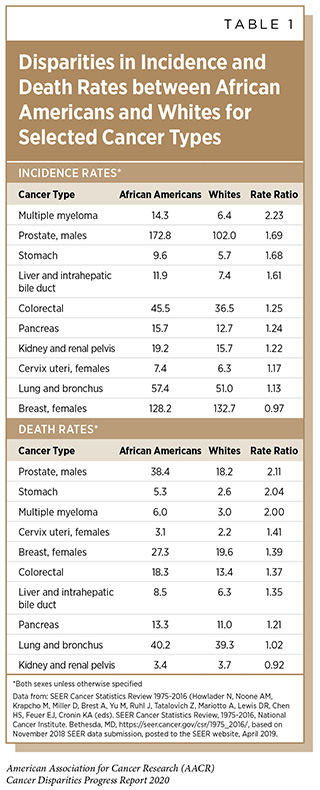

For many of the most common types of cancer, including breast, lung, prostate, and colorectal cancers, incidence and/or death rates are higher among African Americans than other racial and ethnic groups (see Table 1). One of the most striking examples of cancer-specific disparities is that African American men have prostate cancer incidence and death rates that are more than 1.5-times and more than 2-times those for men of any other race or ethnicity, respectively (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The disparity in prostate cancer mortality between African American men and men of any other race or ethnicity was recently shown to be greatest for those diagnosed with low-grade prostate cancer (14)Mahal BA, Berman RA, Taplin M-E, Huang FW. Prostate Cancer–Specific Mortality Across Gleason Scores in Black vs Nonblack Men. JAMA [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];320:2479.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. There are many factors that contribute to the high burden of prostate cancer mortality among African American men, including higher prostate cancer incidence rates among this population group. In addition, research has shown that prostate cancer in African American men is more likely to be aggressive (fast growing) and that African American men are less likely to receive cutting-edge treatment after a prostate cancer diagnosis (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

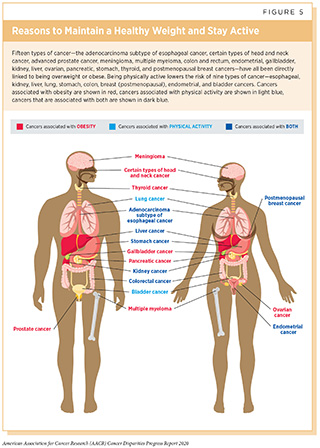

Multiple myeloma and stomach cancer are two other types of cancer for which African Americans have a death rate that is at least double that for whites (see Table 1). The incidence rates for these two types of cancer are also much higher among African Americans than among whites. One factor that may contribute to the higher burden of stomach cancer among African Americans is that infection with the cancer-causing bacterium Helicobacter pylori is more than twice as common among African Americans compared with whites (15)Grad YH, Lipsitch M, Aiello AE. Secular Trends in Helicobacter pylori Seroprevalence in Adults in the United States: Evidence for Sustained Race/Ethnic Disparities. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 11];175:54–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Risk Factors). For multiple myeloma, among African Americans higher rates of obesity, which is a risk factor for the disease (see Figure 5), and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, which is a blood condition that can progress to multiple myeloma, may contribute to incidence rate disparities (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition to higher incidence rates, poorer access to new, cutting-edge treatments may contribute to the higher multiple myeloma death rates among African Americans (16)Fiala MA, Wildes TM. Racial disparities in treatment use for multiple myeloma. Cancer. United States; 2017;123:1590–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Substantial disparities in colorectal cancer incidence and death rates between African Americans and whites have existed for many years (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].(17)Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of Socioeconomic Disparities in Colorectal Cancer and Intervention Framework and Strategies. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 22];158:354–67.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among the factors that contribute to the colorectal cancer incidence rate disparity between African Americans and whites are higher rates of obesity, which is a risk factor for the disease (see Figure 5), and lower rates of colorectal cancer screening among African Americans (18)White A, Thompson TD, White MC, Sabatino SA, Moor J de, Doria-Rose P V., et al. Cancer screening test use — United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2017;66:201–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One study estimated that 42 percent of the incidence rate disparity and 19 percent of death rate disparity were attributable to differences in colorectal cancer screening rates (19)Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Jemal A. Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 11];21:728–36.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Other factors contributing to the disparity in the colorectal cancer death rate include differences in where the tumor is located, with African Americans being four times more likely to be diagnosed with right-sided colon cancers, which are more aggressive than left-sided colon cancers, and African Americans having poorer access to new, cutting-edge treatments (20)Thornton JG, Morris AM, Thornton JD, Flowers CR, McCashland TM. Racial variation in colorectal polyp and tumor location. J Natl Med Assoc [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2019 Dec 11];99:723–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(21)Lai Y, Wang C, Civan JM, Palazzo JP, Ye Z, Hyslop T, et al. Effects of Cancer Stage and Treatment Differences on Racial Disparities in Survival From Colon Cancer: A United States Population-Based Study. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];150:1135–46.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among African American women, with 33,840 new cases estimated to have been diagnosed in 2019 alone (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The breast cancer incidence rate has been lower among African American women than it has among white women for several decades (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, the incidence rate among African American women has been rising steadily during that time while it has fluctuated among white women. As a result of the disproportionate increase in the breast cancer incidence rate among African American women, incidence rates for this type of cancer are now very similar for African American and white women. In addition, when considering women under the age of 40, the breast cancer incidence rate is higher among African Americans than it is for any other racial or ethnic group (22)Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020. Am Cancer Soc. 2019;70:515–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In contrast to the incidence rate, the breast cancer death rate is 39 percent higher for African American women compared with white women. Many factors contribute to the breast cancer death rate disparity, including African American women being more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage of disease, when treatment is less likely to be successful, and being more likely to be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, which is a biologically-aggressive disease form of breast cancer with a poor prognosis (22)Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019-2020. Am Cancer Soc. 2019;70:515–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Overall African American–white disparities in lung cancer incidence and death rates are not striking (see Table 1). However, dramatic disparities are evident when men and women are considered separately. The lung cancer incidence rate is 13 percent higher among African American men compared with white men, and it is 14 percent lower among African American women compared with white women (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Similar trends are seen for the lung cancer death rate, which is 18 percent higher among African American men compared with white men and 12 percent lower among African American women compared with white women (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These differences in lung cancer incidence and death rates are in large part due to differences in tobacco exposure among these different population groups. The most recent data show that African American men smoke cigarettes at a higher rate than white men, while African American women smoke cigarettes at a lower rate than white women (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This knowledge is vital if we are to develop targeted approaches to tobacco control that will help eliminate disparities in lung cancer for African American men.

Cancers with a Disproportionate Burden in Hispanics

Hispanics comprise about 18 percent of the U.S. population and are the largest racial and ethnic minority population group in the United States (13)Bureau UC. National Population by Characteristics: 2010-2019. [cited 2020 Jan 22];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. An additional 3.1 million Hispanic U.S. citizens live in Puerto Rico (23)U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Puerto Rico [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 11].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

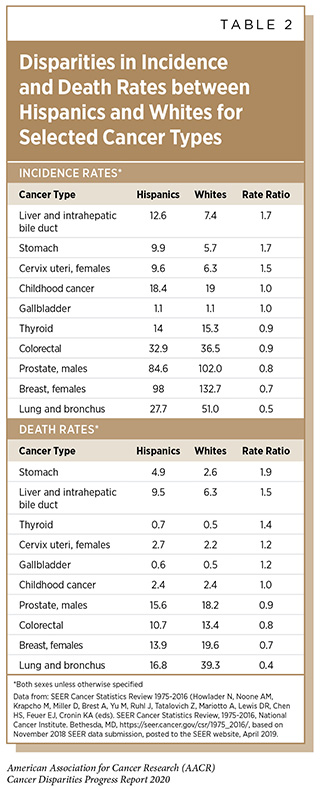

The overall cancer incidence and death rates are 25 percent and 32 percent lower among Hispanics in the continental United States and Hawaii than among whites (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Hispanics also have lower incidence and death rates compared with whites for the types of cancer most commonly diagnosed in the United States including the five most common types of cancer—breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15].(24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, incidence and death rates for numerous other types of cancer are significantly higher among Hispanics (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Table 2).

It is important to note that the Hispanic population in the continental United States and Hawaii is highly diverse. For certain types of cancer, differences in incidence and death rates have been reported by country or region of origin, and for populations with differing degrees of ancestry from Indigenous Americans, Europeans, and Africans (25)Zamora SM, Pinheiro PS, Gomez SL, Hastings KG, Palaniappan LP, Hu J, et al. Disaggregating Hispanic American Cancer Mortality Burden by Detailed Ethnicity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 11];28:1353–63.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(26)Fejerman L, John EM, Huntsman S, Beckman K, Choudhry S, Perez-Stable E, et al. Genetic Ancestry and Risk of Breast Cancer among U.S. Latinas. Cancer Res [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:9723–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(27)Pinheiro PS, Sherman RL, Trapido EJ, Fleming LE, Huang Y, Gomez-Marin O, et al. Cancer Incidence in First Generation U.S. Hispanics: Cubans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and New Latinos. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Dec 11];18:2162–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. There are also differences between U.S.-born and foreign-born Hispanics (28)Stern MC, Fejerman L, Das R, Setiawan VW, Cruz-Correa MR, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. No Title. Springer; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];3:181–90.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., and between Hispanics in the continental United States and Hawaii and those in Puerto Rico (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One powerful example of the difference in cancer burden between Hispanics in the continental United States and Hawaii and those in Puerto Rico is that the prostate cancer incidence rate among Hispanic men in Puerto Rico is 60 percent higher compared with Hispanic men in the continental United States and Hawaii (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Liver cancer is one of the types of cancer with the most striking disparities in incidence and death rates between Hispanics and whites in the continental United States and Hawaii (see Table 2). Several studies have shown that among Hispanic men in the continental United States and Hawaii, those born in the United States have a liver cancer incidence rate that is nearly double that of those born outside the United States (28)Stern MC, Fejerman L, Das R, Setiawan VW, Cruz-Correa MR, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. No Title. Springer; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];3:181–90.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(29)Setiawan VW, Wei PC, Hernandez BY, Lu SC, Monroe KR, Le Marchand L, et al. No Title. Cancer [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];122.[cited 2020 Jul 15].; rates are comparable between U.S.- and foreign-born Hispanic women. In addition, Puerto Rican Hispanic men living on the U.S. mainland have a higher liver cancer incidence rate than those living on the island of Puerto Rico (30)Ho GYF, Figueroa-Vallés NR, De La Torre-Feliciano T, Tucker KL, Tortolero-Luna G, Rivera WT, et al. Cancer disparities between mainland and island Puerto Ricans. Rev Panam Salud Publica [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Dec 11];25:394–400.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Disparities in liver cancer incidence rates are in large part attributable to higher rates of exposure to risk factors for liver cancer—such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, and diabetes (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Risk Factors)—among the populations disproportionately shouldering the burden of this devastating disease. However, not all the disparities seem to be explained by higher rates of known risk factors, suggesting that additional risk factors need to be identified (28)Stern MC, Fejerman L, Das R, Setiawan VW, Cruz-Correa MR, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. No Title. Springer; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];3:181–90.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(29)Setiawan VW, Wei PC, Hernandez BY, Lu SC, Monroe KR, Le Marchand L, et al. No Title. Cancer [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];122.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Stomach cancer is another type of cancer with dramatic disparities in incidence and death rates between Hispanics and whites in the continental United States and Hawaii (see Table 2). Hispanic women experience greater disparities in stomach cancer incidence and death rates than Hispanic men, with both rates more than twice as high for Hispanic women compared with white women while stomach cancer incidence and death rates are 61 percent and 98 percent higher, respectively for Hispanic men compared with white men (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One study also reported differences in stomach cancer death rates among different groups of Hispanics living in Florida, with rates among Hispanics from Spanish-speaking countries in Central America and South America more than double the rate among Hispanics from Cuba (31)Pinheiro PS, Callahan KE, Siegel RL, Jin H, Morris CR, Trapido EJ, et al. Cancer Mortality in Hispanic Ethnic Groups. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 11];26:376–82.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The disparities in stomach cancer incidence rates are in large part attributable to differences in rates of exposure to risk factors for the disease, in particular, chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori and obesity (24)Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Cancer Statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:425–45.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Cervical cancer incidence and death rates have been substantially higher among Hispanic women than they have among white women for the past two decades (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Table 2). One key factor contributing to these disparities is the fact that the rate of cervical cancer screening is lower among Hispanic women compared with white women (18)White A, Thompson TD, White MC, Sabatino SA, Moor J de, Doria-Rose P V., et al. Cancer screening test use — United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2017;66:201–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. As we look to the future, there is hope that disparities in cervical cancer incidence and death rates can be eliminated because rates of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, which can prevent infection with the virus that causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer, are higher among Hispanic adolescents compared with white adolescents (32)Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:718–23.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The overall incidence rates for childhood cancer (cancer diagnosed from age 0 to 14) and for adolescent cancer (cancer diagnosed from age 15 to 19) are very similar among Hispanic children and adolescents compared with white children and adolescents, respectively (5)American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics / Latinos 2018-2020. 2018;42.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, Hispanic children and adolescents have the highest leukemia incidence rate of any racial and ethnic group in the United States (5). Five-year relative survival is also lower for Hispanic children diagnosed with leukemia, compared with white children. Differences in disease biology, access to treatment, and treatment efficacy are all factors that may contribute to this disparity in survival (5).

Cancers with a Disproportionate Burden in Asians/Pacific Islanders

The Asian American population, which encompasses people living in the United States who have origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent, comprises about 6 percent of the U.S. population (13)Bureau UC. National Population by Characteristics: 2010-2019. [cited 2020 Jan 22];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Cancer statistics for the Asian American population are aggregated with those for the Pacific Islander population, even though these two populations are distinct racial groups. The Pacific Islander population, which encompasses people living in the United States who have origins in Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands, comprises about 0.4 percent of the U.S. population (33)Bureau USC. American FactFinder. [cited 2019 Dec 11];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The Asian/Pacific Islander population has the lowest overall cancer incidence and death rates of any racial and ethnic group in the United States (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15].(34)American Cancer Society. Facts & Figures 2019. Am Cancer Soc Atlanta, Ga. 2019;[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Figure 1). When compared with whites, the overall cancer incidence and death rates for Asian/Pacific Islanders are 34 percent and 38 percent lower, respectively. Asian/Pacific Islanders also have lower incidence and death rates compared with whites for the types of cancer most commonly diagnosed in the United States, including the five most common types of cancer—breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15].(34)American Cancer Society. Facts & Figures 2019. Am Cancer Soc Atlanta, Ga. 2019;[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

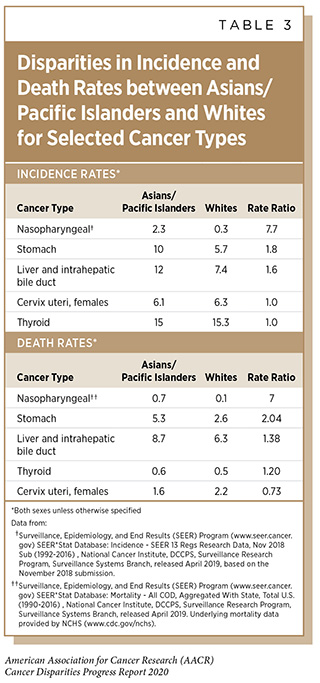

However, incidence and death rates for some types of cancer are significantly higher among the Asian/Pacific Islander population (see Table 3). For example, incidence and death rates for nasopharyngeal cancer, which is frequently caused by infection with Epstein-Barr virus, are about seven-fold higher among Asian/Pacific Islanders compared with whites.

It is important to note that the Asian/Pacific Islander population is very diverse and differences in cancer-specific incidence and death rates have been reported by country or region of origin for selected cancers (35)Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Am Cancer Soc. 2011;122:532–5.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, lung cancer incidence rates are four-times higher among men and women of Samoan origin compared with men and women of Asian Indian/Pakistani origin, and these differences reflects differences in smoking rates among the population groups. In addition, the stomach cancer incidence rates among men and women of Korean origin are almost double those among men and women of Japanese origin who have the second highest rates among Asian/Pacific Islander populations.

Cancers with a Disproportionate Burden in American Indians/Alaska Natives

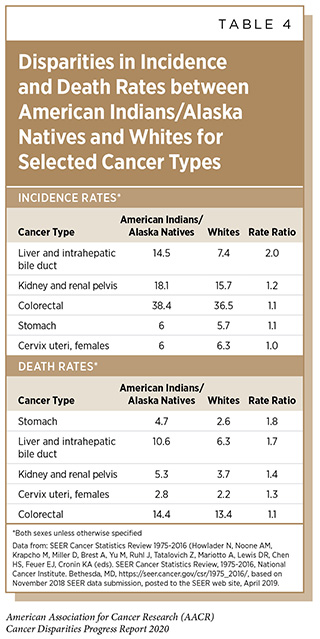

The American Indian/Alaskan Native population comprises about 1.7 percent of the U.S. population (33)Bureau USC. American FactFinder. [cited 2019 Dec 11];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. When compared with whites, the overall cancer incidence and death rates for American Indian/Alaskan Natives are 14 percent and 10 percent lower, respectively (34)American Cancer Society. Facts & Figures 2019. Am Cancer Soc Atlanta, Ga. 2019;[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, incidence and death rates for some types of cancer are significantly higher among the American Indian/Alaskan Natives compared with whites (see Table 4). Disparities in liver cancer incidence and death rates between American Indians/Alaskan Natives and whites are particularly striking and are in large part due to American Indian/Alaskan Natives having higher rates of exposure to risk factors for liver cancer such as HBV infection, HCV infection, chronic liver disease, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, and diabetes (36)Melkonian SC, Jim MA, Reilley B, Erdrich J, Berkowitz Z, Wiggins CL, et al. Incidence of primary liver cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives, US, 1999-2009. Cancer Causes Control [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 11];29:833–44.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

It is important to note that cancer incidence and death rates vary among American Indian/Alaskan Natives living in different Indian Health Service regions (37)White MC, Espey DK, Swan J, Wiggins CL, Eheman C, Kaur JS. Disparities in cancer mortality and incidence among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States. Am J Public Health [Internet]. American Public Health Association; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 11];104 Suppl 3:S377-87.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, American Indians/Alaska Natives in three of the six Indian Health Service regions—Alaska, Northern Plains, and Southern Plains—have higher overall cancer death rates compared with whites, those in the Pacific Coast region have a comparable overall cancer death rate, and those in the East or Southwest regions have lower overall cancer death rates compared with whites. There are also differences in incidence and death rates for specific types of cancer among American Indians/Alaska Natives in the different Indian Health Service regions. For example, while the breast cancer death rate for all American Indian/Alaska Native women combined is lower than that for white women, the breast cancer death rates for American Indian/Alaska Native women in Alaska and the Southern Plains are 26 percent and 18 percent higher, respectively, compared with that for white women. In addition, lung cancer incidence rates among American Indian/Alaska Native men in Alaska and the Northern Plains are 45 percent and 54 percent higher, respectively, compared with that for white men but American Indian/Alaska Native men in the Southwest have a 65 percent lower lung cancer incidence rate compared with white men. Cancer disparities between Indian Health Service regions reflect different exposures to risk factors and access to care and understanding what these disparities are is important for developing and implementing region-appropriate strategies to eliminate the disparities.

Why Do Cancer Health Disparities Exist?

Decades of research have identified many factors that contribute to cancer health disparities. These factors are complex and interrelated (see sidebar on Why Do U.S. Cancer Health Disparities Exist?). Among the most important factors are social determinants of health, which are defined by the NCI as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, including the health system (38)Health Disparities | DCCPS/NCI/NIH [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 16].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Social determinants of health, which can be considered at the level of individuals, groups, communities, or societies (39)Singh GK, Daus GP, Allender M, Ramey CT, Martin EK, Perry C, et al. Social Determinants of Health in the United States: Addressing Major Health Inequality Trends for the Nation, 1935-2016. Int J MCH AIDS [Internet]. Global Health and Education Projects, Inc.; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];6:139–64.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., are the factors that provide the context within which cancer is detected, treated, and prevented (40)Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, Yabroff KR, Guerra CE, Wender RC. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 22];70:31–46.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(17)Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of Socioeconomic Disparities in Colorectal Cancer and Intervention Framework and Strategies. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 22];158:354–67.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Biological factors also play a role in cancer health disparities and may increase the risk of disparities in cancer outcomes through their interaction with social determinants of health.

Increased realization of the importance of social determinants to the health of the Nation led the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to include “Create social and physical environments that promote good health” as one of the four overarching goals of the Healthy People 2020 initiative (41)Kickbusch I, McCann W, Sherbon T. Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. Health Promot Int [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 16];23:1–4.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. There are also efforts to develop standardized tools to obtain information from patients about social determinants of health and to develop standardized measures of contextual factors, such as social, cultural, and physical environment (42)Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 16].[cited 2020 Jul 15].(43)Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable Health Communities — Addressing Social Needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 16];374:8–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Information on social determinants of health from patients has the potential to help clinicians better care for and support the patients, and when combined with information on contextual factors, patient information can be used by cancer health disparities researchers to gain a more integrated and comprehensive understanding of the interrelationship of the various factors, which is vital if we are to achieve health equity.

Social Factors Contributing to Cancer Health Disparities

Inequalities in socioeconomic status, at the level of individuals, neighborhoods, and regions, are among the most important social factors contributing to cancer health disparities in the United States (6)Siegel RL, Miller KD. Cancer Statistics , 2019. 2019;69:7–34.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One recent study estimated that eliminating socioeconomic disparities could prevent 34 percent of cancer deaths among all U.S. adults ages 25 to 74 (45)Siegel RL, Jemal A, Wender RC, Gansler T, Ma J, Brawley OW. An assessment of progress in cancer control. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. American Cancer Society; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];68:329–39.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Socioeconomic status is most often determined based on income, education level, and occupation, and each of these components contributes to cancer health disparities among individuals of all races (6)Siegel RL, Miller KD. Cancer Statistics , 2019. 2019;69:7–34.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(45)Siegel RL, Jemal A, Wender RC, Gansler T, Ma J, Brawley OW. An assessment of progress in cancer control. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. American Cancer Society; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];68:329–39.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, the colorectal cancer death rate among men living in the poorest counties in the United States is 35 percent higher than that for men living in the most affluent counties (6)Siegel RL, Miller KD. Cancer Statistics , 2019. 2019;69:7–34.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. and the lung cancer death rate among U.S. adults who have 12 or fewer years of education is almost four times higher than that for those who have 16 or more years of education (45)Siegel RL, Jemal A, Wender RC, Gansler T, Ma J, Brawley OW. An assessment of progress in cancer control. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. American Cancer Society; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];68:329–39.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

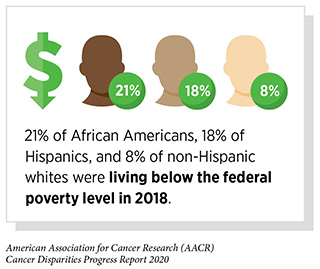

Inequalities in socioeconomic status and its components are also factors that contribute to racial and ethnic cancer health disparities because socioeconomic disadvantages are disproportionately more common among racial and ethnic minority groups. For example, 21 percent of African Americans and 18 percent of Hispanics were living below the federal poverty level in 2018 compared with 8 percent of whites who are not of Hispanic ancestry (non-Hispanic whites) (46)Index of /programs-surveys/demo/tables [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 22].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition, just 25 percent of African Americans and 18 percent of Hispanics have attained a bachelor’s degree or higher educational qualification compared with 35 percent of all whites (46)Index of /programs-surveys/demo/tables [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 22].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The socioeconomic status of individuals and neighborhoods can affect clinical, environmental, psychological, behavioral, and cultural factors that influence health, including access to healthy foods, spaces for physical activity, the Internet, and transportation, as well as exposure to crime, violence, and social disorder, such as the presence of trash. Establishing how much each factor contributes to racial and ethnic cancer health disparities is vital if we are to engage new sectors, such as education, housing, transportation, agriculture, and environment, in efforts to achieve cancer health equity.

Clinical Factors Contributing to Cancer Health Disparities

Inequalities in access to clinical care and the quality of care received are important modifiable clinical factors that contribute to cancer health disparities. Quality is often measured based on whether individuals receive guideline-recommended care and whether they are treated at a facility that has the experience and infrastructure to care for cancer patients. Research has shown that racial and ethnic minorities often receive lower quality care compared to whites (47)Ransome E, Tong L, Espinosa J, Chou J, Somnay V, Munene G. Trends in surgery and disparities in receipt of surgery for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the US: 2005-2014. J Gastrointest Oncol [Internet]. AME Publications; 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 20];10:339–47.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(16)Fiala MA, Wildes TM. Racial disparities in treatment use for multiple myeloma. Cancer. United States; 2017;123:1590–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(48). For example, African Americans and Hispanics with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma are 50 percent and 41 percent less likely to have surgery, respectively, compared with whites (47)Ransome E, Tong L, Espinosa J, Chou J, Somnay V, Munene G. Trends in surgery and disparities in receipt of surgery for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the US: 2005-2014. J Gastrointest Oncol [Internet]. AME Publications; 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 20];10:339–47.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., and patients with multiple myeloma who are African American are 21 percent less likely to receive the molecularly targeted therapeutic bortezomib compared with whites (16)Fiala MA, Wildes TM. Racial disparities in treatment use for multiple myeloma. Cancer. United States; 2017;123:1590–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

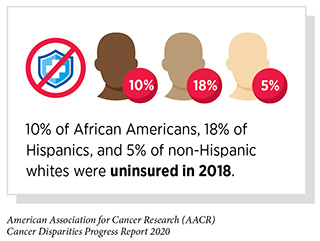

Health insurance status is one of the most important factors determining access to quality cancer care. Individuals who lack health insurance have a higher risk of poor outcomes from cancer compared with those who are insured (49)Pan HY, Walker G V., Grant SR, Allen PK, Jiang J, Guadagnolo BA, et al. Insurance Status and Racial Disparities in Cancer-Specific Mortality in the United States: A Population-Based Analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];26:869–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(50)Niu X, Roche LM, Pawlish KS, Henry KA. Cancer survival disparities by health insurance status. Cancer Med [Internet]. Wiley-Blackwell; 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 16];2:403–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(51)Rong X, Yang W, Garzon-Muvdi T, Caplan JM, Hui X, Lim M, et al. Influence of insurance status on survival of adults with glioblastoma multiforme: A population-based study. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 16];122:3157–65.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(52)Markt SC, Lago-Hernandez CA, Miller RE, Mahal BA, Bernard B, Albiges L, et al. Insurance status and disparities in disease presentation, treatment, and outcomes for men with germ cell tumors. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 16];122:3127–35.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(53)Pezzi TA, Schwartz DL, Mohamed ASR, Welsh JW, Komaki RU, Hahn SM, et al. Barriers to Combined-Modality Therapy for Limited-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];4:e174504.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, one study found that cancer patients who were uninsured were 45 percent more likely to die from their cancer compared with those who had non-Medicaid insurance, which includes private insurance, Medicare, and military coverage (49)Pan HY, Walker G V., Grant SR, Allen PK, Jiang J, Guadagnolo BA, et al. Insurance Status and Racial Disparities in Cancer-Specific Mortality in the United States: A Population-Based Analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];26:869–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among the reasons that a lack of health insurance contributes to cancer health disparities is that compared with individuals who have private insurance, those who are uninsured are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage of disease, which decreases the likelihood of treatment being successful, and are less likely to receive standard treatments (51)Rong X, Yang W, Garzon-Muvdi T, Caplan JM, Hui X, Lim M, et al. Influence of insurance status on survival of adults with glioblastoma multiforme: A population-based study. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 16];122:3157–65.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(52)Markt SC, Lago-Hernandez CA, Miller RE, Mahal BA, Bernard B, Albiges L, et al. Insurance status and disparities in disease presentation, treatment, and outcomes for men with germ cell tumors. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 16];122:3127–35.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(53)Pezzi TA, Schwartz DL, Mohamed ASR, Welsh JW, Komaki RU, Hahn SM, et al. Barriers to Combined-Modality Therapy for Limited-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];4:e174504.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer who were uninsured were 35 percent less likely to receive chemotherapy and 25 percent less likely to receive radiotherapy compared with those who had private or managed care health insurance, and not receiving these treatments was, in turn, associated with poor survival (53)Pezzi TA, Schwartz DL, Mohamed ASR, Welsh JW, Komaki RU, Hahn SM, et al. Barriers to Combined-Modality Therapy for Limited-Stage Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];4:e174504.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be uninsured or receive Medicaid compared with whites, and health insurance status is a key factor contributing to racial and ethnic cancer health disparities (54)Bureau UC. Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2018. [cited 2019 Dec 16];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One recent study showed that African American, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and Hispanic women were more than 30 percent more likely to be diagnosed with advanced stage breast cancer compared with white women and that nearly half of this disparity was a result of these women being uninsured or receiving Medicaid (55)Ko NY, Hong S, Winn RA, Calip GS. Association of Insurance Status and Racial Disparities With the Detection of Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 22];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Although these data and results from other studies show that addressing health insurance status will not completely mitigate cancer health disparities, providing equal insurance coverage has the potential to reduce the burden of cancer for racial and ethnic minorities (49)Pan HY, Walker G V., Grant SR, Allen PK, Jiang J, Guadagnolo BA, et al. Insurance Status and Racial Disparities in Cancer-Specific Mortality in the United States: A Population-Based Analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];26:869–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The complexity of the issue of access to quality cancer care is not only influenced by health insurance status, but is also influenced by factors such as whether an individual will accept or decline to use cancer care services and treatment: if the services are easy or difficult to use; if individuals can get to the facilities where care is being offered; language barriers orfear of discrimination; and whether individuals have enough health literacy to make the best decisions for their care (56)Morales J, Malles A, Kimble M, Rodriguez de la Vega P, Castro G, Nieder AM, et al. Does Health Insurance Modify the Association Between Race and Cancer-Specific Survival in Patients with Urinary Bladder Malignancy in the U.S.? Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 8];16:3393.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Behavioral and Cultural Factors Contributing to Cancer Health Disparities

In the United States, it is estimated that four out of 10 cancer cases and almost half of all cancer-related deaths are caused by potentially modifiable risk factors (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among the potentially modifiable factors with the biggest impact on cancer risk are tobacco use, poor diet, alcohol intake, physical inactivity, obesity, infection with cancer-causing pathogens, and exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation (see Figure 2). There are striking racial and ethnic disparities in the burden of many of the potentially modifiable cancer risk factors, as discussed in Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Risk Factors, and these are important behavioral factors contributing to cancer health disparities. Other behavioral factors, which are also influenced by clinical, cultural, and social factors, include racial and ethnic disparities in adherence to cancer screening recommendations and in rapidly obtaining cancer treatment (see Disparities in Cancer Screening).

Given our knowledge of the behavioral factors related to cancer health disparities, it is clear that strategies that promote behavior modification, for example, eliminating tobacco use, increasing consumption of a healthy and balanced diet, and participating regularly in physical exercise, could help eliminate or reduce some racial and ethnic cancer health disparities. One statewide initiative designed to address this is Double Up Food Bucks (DUFB) in Michigan, which matches Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) funds spent at farmers’ markets. Uptake of DUFB was initially low, but a brief intervention, explaining the initiative to those eligible, resulted in a fourfold increase in uptake, as well as significant increases in fruit and vegetable consumption in a low-income, racially and ethnically diverse community in Michigan (58)Cohen AJ, Richardson CR, Heisler M, Sen A, Murphy EC, Hesterman OB, et al. Increasing Use of a Healthy Food Incentive: A Waiting Room Intervention Among Low-Income Patients. Am J Prev Med [Internet]. Elsevier; 2017;52:154–62.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

An important component of developing strategies to foster behavior modification is identifying and understanding cultural factors, including cultural health beliefs, that influence behavior. For example, a recent study showed that a single-session educational intervention designed and tailored to the Pacific Islander community in southern California increased cervical cancer screening by Pap testing in that community (59)Tanjasiri SP, Mouttapa M, Sablan-Santos L, Weiss JW, Chavarria A, Lacsamana JD, et al. Design and Outcomes of a Community Trial to Increase Pap Testing in Pacific Islander Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];28:1435–42.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Psychological Factors Contributing to Cancer Health Disparities

There is growing evidence that psychological stress and stress responses are associated with higher overall cancer incidence and mortality, as well as poorer overall cancer survival (60)Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 16];5:466–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, psychological distress, such as ongoing depression and anxiety-related symptoms, is associated with a 97 percent increased risk for cancer mortality in people with a history of cancer (61)Hamer M, Chida Y, Molloy GJ. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. J Psychosom Res [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Dec 16];66:255–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The extent to which psychological factors are associated with cancer burden varies for different types of cancer. For example, one factor that influences cervical cancer incidence is adherence to screening recommendations, and research has shown that women who report having had a greater number of major traumatic or stressful life events, or having greater feelings of discrimination, were 85 percent and 17 percent more likely not to be up to date with cervical cancer screening recommendations, respectively (62)Paskett ED, McLaughlin JM, Reiter PL, Lehman AM, Rhoda DA, Katz ML, et al. Psychosocial predictors of adherence to risk-appropriate cervical cancer screening guidelines: a cross sectional study of women in Ohio Appalachia participating in the Community Awareness Resources and Education (CARE) project. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2010 [cited 2019 Dec 16];50:74–80.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. With regards to cancer type-specific outcomes, stress has been linked to poorer outcomes for patients with breast, lung, head and neck, hepatobiliary, and lymphoid or hematopoietic cancers (60)Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 16];5:466–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, women with breast cancer who report no traumatic or stressful life events have been found to have a disease-free interval that is twice as long as those who have experienced one or more stressful or traumatic life events (63)Palesh O, Butler LD, Koopman C, Giese-Davis J, Carlson R, Spiegel D. Stress history and breast cancer recurrence. J Psychosom Res [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2019 Dec 16];63:233–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition, cancer patients whose marital status is separated at the time of diagnosis have a 10-year relative survival rate that is 36 percent lower than that for those who are married at the time of diagnosis (64)Sprehn GC, Chambers JE, Saykin AJ, Konski A, Johnstone PAS. Decreased cancer survival in individuals separated at time of diagnosis: critical period for cancer pathophysiology? Cancer [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2009 [cited 2019 Dec 16];115:5108–16.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Psychological stress is also emerging as an important factor in cancer health disparities, with researchers finding that levels of emotional distress are significantly higher among African American cancer survivors compared with cancer survivors from other racial and ethnic groups (65)Apenteng BA, Hansen AR, Opoku ST, Mase WA. Racial Disparities in Emotional Distress Among Cancer Survivors: Insights from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J Cancer Educ [Internet]. Springer; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];32:556–65.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Psychosocial stressors have also been shown to contribute to the increased risk of certain aggressive types of breast cancer among African American women (66)Linnenbringer E, Gehlert S, Geronimus AT. Black-White Disparities in Breast Cancer Subtype: The Intersection of Socially Patterned Stress and Genetic Expression. AIMS public Heal [Internet]. AIMS Press; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];4:526–56.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Identifying how psychological factors, including experiences of stress, influence cancer progression is an area of intensive research investigation because this knowledge has the potential to help researchers develop prevention and intervention strategies. These, in turn, could be used to help eliminate cancer health disparities.

Environmental Factors Contributing to Cancer Health Disparities

The HHS recognizes that a person’s physical environment influences health (41)Kickbusch I, McCann W, Sherbon T. Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. Health Promot Int [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 16];23:1–4.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, an individual’s physical environment determines access to healthy foods and spaces for physical activity, which are linked to improved health, including decreased risk for cancer and improved cancer outcomes; it determines access to transportation, which individuals may need to obtain cancer clinical care; it determines proximity to quality cancer care facilities; and it determines exposure to toxic substances, crime, violence, and social disorder, such as the presence of trash, which are all associated with poorer health, including increased risk for cancer and poorer cancer outcomes.

Research has shown that individuals living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage cancer and to have poorer survival compared with individuals in more advantaged neighborhoods (67)DeGuzman PB, Cohn WF, Camacho F, Edwards BL, Sturz VN, Schroen AT. Impact of Urban Neighborhood Disadvantage on Late Stage Breast Cancer Diagnosis in Virginia. J Urban Health [Internet]. Springer; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];94:199.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(68)Guan A, Lichtensztajn D, Oh D, Jain J, Tao L, Hiatt RA, et al. Breast Cancer in San Francisco: Disentangling Disparities at the Neighborhood Level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];28:1968–76.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(69)DeRouen MC, Schupp CW, Koo J, Yang J, Hertz A, Shariff-Marco S, et al. Impact of individual and neighborhood factors on disparities in prostate cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];53:1–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, women in disadvantaged urban neighborhoods are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer and men in disadvantaged neighborhoods who are diagnosed with prostate cancer have poorer survival (67)DeGuzman PB, Cohn WF, Camacho F, Edwards BL, Sturz VN, Schroen AT. Impact of Urban Neighborhood Disadvantage on Late Stage Breast Cancer Diagnosis in Virginia. J Urban Health [Internet]. Springer; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];94:199.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(68)Guan A, Lichtensztajn D, Oh D, Jain J, Tao L, Hiatt RA, et al. Breast Cancer in San Francisco: Disentangling Disparities at the Neighborhood Level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];28:1968–76.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(69)DeRouen MC, Schupp CW, Koo J, Yang J, Hertz A, Shariff-Marco S, et al. Impact of individual and neighborhood factors on disparities in prostate cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];53:1–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Disparities in physical environment contribute to racial and ethnic cancer health disparities. For example, one study found that African American women were significantly more likely to live in disadvantaged neighborhoods than white women and that this was an important factor contributing to African American–white disparities in triple-negative breast cancer stage at diagnosis and survival (70)Hossain F, Danos D, Prakash O, Gilliland A, Ferguson TF, Simonsen N, et al. Neighborhood Social Determinants of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Front public Heal [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 22];7:18.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In other studies, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood has been shown to contribute to disparities between African Americans and whites in liver cancer incidence and prostate cancer survival (69)DeRouen MC, Schupp CW, Koo J, Yang J, Hertz A, Shariff-Marco S, et al. Impact of individual and neighborhood factors on disparities in prostate cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];53:1–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(71)Danos D, Leonardi C, Gilliland A, Shankar S, Srivastava RK, Simonsen N, et al. Increased Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Associated With Neighborhood Concentrated Disadvantage. Front Oncol [Internet]. Frontiers Media SA; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];8:375.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Given the important contribution of physical environment to cancer health disparities, we must engage new sectors, such as education, housing, transportation, agriculture, and environment, in efforts to achieve cancer health equity.

Biological and Genetic Factors Contributing to Cancer Health Disparities

Following completion of the Human Genome Project there has been significant interest in understanding the association between genetic and biological factors and cancer health disparities. However, genetic studies that include minority populations are still significantly underrepresented compared with studies that include individuals of European descent (see Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Disparities). Nevertheless, emerging evidence supports a role for genetic and biological differences among populations as factors associated with cancer health disparities. For example, numerous studies have uncovered ancestry-related differences in prostate cancers and breast cancers from African Americans and whites at the level of DNA, RNA, and proteins (72)Hardiman G, Savage SJ, Hazard ES, Wilson RC, Courtney SM, Smith MT, et al. Systems analysis of the prostate transcriptome in African–American men compared with European–American men. Pharmacogenomics [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 16];17:1129–43.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(73)Teslow EA, Bao B, Dyson G, Legendre C, Mitrea C, Sakr W, et al. Exogenous IL-6 induces mRNA splice variant MBD2_v2 to promote stemness in TP53 wild-type, African American PCa cells. Mol Oncol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];12:1138–52.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(74)Wallace TA, Prueitt RL, Yi M, Howe TM, Gillespie JW, Yfantis HG, et al. Tumor Immunobiological Differences in Prostate Cancer between African-American and European-American Men. Cancer Res [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 16];68:927–36.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(75)Robinson TJ, Freedman JA, Al Abo M, Deveaux AE, LaCroix B, Patierno BM, et al. Alternative RNA Splicing as a Potential Major Source of Untapped Molecular Targets in Precision Oncology and Cancer Disparities. Clin Cancer Res [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];25:2963–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(76)Jenkins BD, Martini RN, Hire R, Brown A, Bennett B, Brown I, et al. Atypical Chemokine Receptor 1 ( DARC/ACKR1 ) in Breast Tumors Is Associated with Survival, Circulating Chemokines, Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells, and African Ancestry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];28:690–700.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(77)Huo D, Hu H, Rhie SK, Gamazon ER, Cherniack AD, Liu J, et al. Comparison of Breast Cancer Molecular Features and Survival by African and European Ancestry in The Cancer Genome Atlas. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];3:1654.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Ancestry-related genetic differences have also been associated with differences in risk for breast cancer among African Americans, Hispanics, and whites (28)Stern MC, Fejerman L, Das R, Setiawan VW, Cruz-Correa MR, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. No Title. Springer; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];3:181–90.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(78)Wang S, Pitt JJ, Zheng Y, Yoshimatsu TF, Gao G, Sanni A, et al. Germline variants and somatic mutation signatures of breast cancer across populations of African and European ancestry in the US and Nigeria. Int J Cancer [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];145:3321–33.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(79)Rey-Vargas L, Sanabria-Salas MC, Fejerman L, Serrano-Gómez SJ. Risk Factors for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer among Latina Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];28:1771–83.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. How and to what extent these genetic and biological factors contribute to racial and ethnic cancer health disparities is an area of intensive research investigation, as is the interplay between these factors and social determinants of health.

Health Disparities: A Costly Public Health Challenge; Health Equity: A Vital Investment

The immense toll of cancer in the United States is felt through both the number of lives it affects each year and its economic impact. One study projected that the direct medical costs of cancer care will be more than $157 billion in 2020, an increase of 27 percent since 2010 (80)Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 16];103:117–28.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This number does not include the indirect costs of lost productivity due to cancer-related morbidity and mortality, which are also extremely high. In fact, a recent analysis estimated that cancer deaths among Americans ages 16 to 84 resulted in $94.4 billion in lost earnings in 2015 alone (81)Islami F, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Zheng Z, Zhao J, Han X, et al. National and State Estimates of Lost Earnings From Cancer Deaths in the United States. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];5:e191460.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Importantly, racial and ethnic health disparities, including cancer health disparities, exert enormous direct medical costs and indirect costs through loss of productivity (82)LaVeist TA, Gaskin D, Richard P. Estimating the Economic Burden of Racial Health Inequalities in the United States. Int J Heal Serv [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 16];41:231–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(83)Men’s Health Equity: A Handbook – Google Books [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 16].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One study projected that eliminating health disparities for racial and ethnic minorities would have reduced direct medical costs by about $230 billion and indirect costs associated with illness and premature death by more than $1 trillion from 2003 to 2006 (82)LaVeist TA, Gaskin D, Richard P. Estimating the Economic Burden of Racial Health Inequalities in the United States. Int J Heal Serv [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 16];41:231–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In another study, it was estimated that $24.2 billion of the $447.6 billion in direct medical costs for African American men from 2006 to 2009 were excess costs attributed to health disparities (83)Men’s Health Equity: A Handbook – Google Books [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 16].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Fortunately, there has been some progress in reducing cancer health disparities, as evidenced by narrowing of racial and ethnic disparities in the overall cancer death rate over the past few years (see Figure 1). This progress is a result of the efforts of all stakeholders committed to eliminating cancer health disparities (see sidebar on Driving Progress against Cancer Health Disparities Together). However, we cannot escape the reality that there is a vital need for more collaboration between the various stakeholders and more cancer health disparities research, which were positions championed by the late Congressman Elijah Cummings.

The field of cancer health disparities research has evolved from simply describing different outcomes among populations into an established multidisciplinary field of research. The increase in the representation of research from diverse disciplines, including anthropology, biology, clinical practice, engineering, education, psychology, and public health, has increased our understanding of the unique interplay between biology, behavior, the environment, and cancer outcomes. As more transdisciplinary approaches are applied in cancer disparities research, we can expect greater understanding of the confluence of factors associated with this public health challenge, the causal pathways, and best approaches for intervention.

Much of the work of cancer health disparities researchers is supported by investments from the federal government, most of which are administered through the 27 institutes and centers of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NCI, which is the federal government’s principal agency for cancer research and training, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) are two of the most important institutes of the NIH for accelerating the pace of progress toward cancer health equity. Within the NCI, the Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (CRCHD) is central to the institute’s efforts to reduce the unequal burden of cancer in the United States. It is imperative, therefore, that Congress continue to provide sustained, robust, and predictable increases in funding for the NIH if cancer health disparities research is to remain a top public health priority and we are to achieve the bold vision of health equity.