Screening for Early Detection

In this section, you will learn:

- Screening for cancer means looking for cancer or abnormal cells that may become cancer in people who do not have any signs of the disease.

- In the United States, independent panels of experts, convened by the government or by professional organizations, carefully evaluate the benefits and harms of cancer screening tests before issuing screening recommendations.

- Extensive research has shown that routine cancer screening saves lives.

- Advances in medical research are underscoring the potential for artificial intelligence and minimally invasive screening tests as new frontiers in early detection of cancer.

- Additional research is needed for early detection of certain cancer types, such as cancers of the ovary, pancreas, and liver, that have high mortality rates but no population-level screening tests.

- Evidence-based interventions can increase adherence to recommended screening guidelines but disparities in the uptake of cancer screening persist.

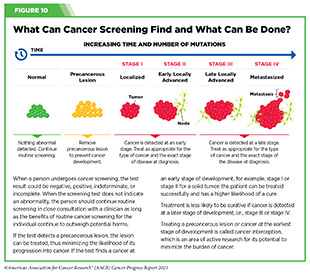

Cancer screening means checking for cancer, or for abnormal cells that may become cancerous, in people who have no signs or symptoms of the disease. Screening for cancer according to evidence-based guidelines can help find aberrations at the earliest possible detectable phase during cancer development and progression. Health care providers use the information gleaned from a cancer screening test to make an informed decision on whether to monitor or treat, or surgically remove, precancerous lesions or early-stage cancer before they progress to a more advanced stage (see Figure 10).

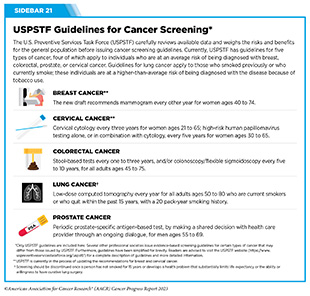

There are different kinds of cancer screening tests that include laboratory tests to determine the changes in cancer biomarkers in biospecimen samples, and imaging or endoscopic procedures to look for specific abnormalities. In the United States, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), an independent Congressionally-mandated panel of experts in preventive care, rigorously reviews the evidence on the benefits and harms of behavioral counseling, preventive medications, and screening strategies related to cancer (see Sidebar 18).

There are other tests beyond those recommended by the USPSTF that are also used by clinicians for detecting cancer. As one example, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not a USPSTF-recommended test, and is not typically used to screen for breast cancer. However, a breast MRI may be performed to further evaluate abnormal findings on mammograms for persons with dense breast tissue, which makes it hard to see abnormal areas on mammography (272)Hussein H, et al. (2023) Radiology, 306: e221785. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers also continually evaluate the safety and accuracy of new and improved methods.

Importance of Cancer Screening

The overarching goal of cancer screening is to reduce the burden of cancer in the general population. Guidelines and recommendations have been created to help individuals and their health care providers decide together whether an individual should be screened for cancer, at what age the screening should start, how frequently the screening should be done and by which method, and if and at what age the screening should stop.

Routine screening aims to catch precancerous lesions or cancer at an early stage when they can be treated more effectively, thus reducing cancer-related deaths (see Figure 10) (274)Crosby D, et al. (2022) Science, 375: eaay9040. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Accruing evidence suggests that recommended cancer screening lowers cancer mortality. In a recent study, researchers analyzed the rate of lung cancer-related mortality from eight clinical trials comprising more than 90,000 participants who received lung cancer screening using either the low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) or chest radiography, or who did not receive lung cancer screening (275)Bonney A, et al. (2022) Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 8: CD013829. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Findings showed a 21 percent reduction in lung cancer-related deaths in participants who were screened for lung cancer using LDCT, compared to the other two groups. Despite the evidence of the benefits, uptake of the recommended lung cancer screening remains suboptimal among eligible individuals (see Sidebar 22).

It is equally vital to receive follow-up testing if the screening test is abnormal, which may indicate the presence of precancerous lesions or cancer. There is strong evidence that many people do not receive follow-up testing after a positive screening test (see Sidebar 22).

One study examined data from more than 32,000 average-risk individuals who had received a positive result from stool-based screening for colorectal cancer between 2017 and 2020. Researchers found that only 53.4 percent received follow-up colonoscopy within one year of receiving the positive result from the initial screening test (276)Mohl JT, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2251384. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This is unfortunate considering recent data, which show that not receiving the follow-up colonoscopy after a positive stool-based test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer (277)Zorzi M, et al. (2022) Gut, 71: 561. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A modeling study estimated a 16 to 23 percent reduction in colorectal cancer-related deaths among individuals who followed up with colonoscopy after a positive stool-based test (278)Kisiel JB, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 6642. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These findings highlight the importance of receiving follow-up testing after an abnormal screening test.

Although risks and benefits of cancer screening tests are carefully considered during the development of screening recommendations, it is important to note that screening tests are medical procedures and carry potential harms. It is thus concerning that a recent study found that not all cancer screening recommendations and guidelines included potential harms associated with screening tests. Researchers reviewed 33 commonly used screening guidelines from various expert panels and found that some harms were not mentioned at all, while others were mentioned only briefly (279)Kamineni A, et al. (2022) Ann Intern Med, 175: 1582. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is vital that the information about benefits and potential harms of cancer screening is clearly and easily available so that people can make an informed and shared decision in consultation with their health care providers (see Sidebar 19).

Guidelines for Cancer Screening

In the United States, guidelines for cancer screening are carefully developed by groups of subject matter experts and professional societies. For example, an independent group of experts convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services carefully evaluates data regarding the benefits and potential harms of different approaches to disease prevention, including cancer screening tests, genetic testing, and preventive therapeutics, to make evidence-based recommendations about the use of these in primary care settings. These volunteer experts form the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). During the development of cancer screening recommendations, USPSTF is supported by researchers from the Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) program, a U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality initiative (see Figure 11).

When developing cancer screening guidelines, subject matter experts such as those who make up USPSTF consider gender and age, as well as additional characteristics that are specific to individuals or population groups for whom the screening guidelines are being developed. These considerations include whether or not a person has a particular organ (e.g., for cervical cancer screening, whether an individual never had a cervix or had a hysterectomy with cervix removal); has a smoking history (e.g., for lung cancer screening); has an all-negative prior screening history (e.g., for cervical cancer screening); has other health-related issues that may reduce life expectancy (e.g., for prostate cancer screening); and/or has a family history of cancer (e.g., for colorectal and breast cancer screening).

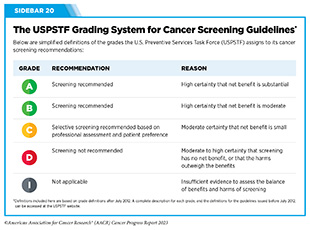

For the finalized guidelines, USPSTF assigns a grade to its recommendations (see Sidebar 20). The grade of evidence also informs which services are covered without out-of-pocket costs under the Affordable Care Act. The USPSTF can assign different grades to different population groups within the same cancer type. For example, a Grade A recommendation is assigned for adults ages 50 to 75 and a Grade B for adults ages 45 to 49 to screen for colorectal cancer.

USPSTF guidance for cancer screening includes recommending for screening certain individuals at certain intervals (see Sidebar 21); recommending against screening that has been shown to be harmful; and deciding that there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. For example, USPSTF recently concluded that there is insufficient current evidence to support visual skin examination as a basis to screen average-risk adolescents and adults for skin cancer (281)Mangione CM, et al. (2023) JAMA, 329: 1290. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Eligibility for Cancer Screening

Cancer screening guidelines are developed for individuals who are at an average risk of being diagnosed with cancer, as well as for those who are at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer.

Key considerations that determine who should receive cancer screening and for which cancer include gender and age. Additional factors considered for cancer screening include genetic, environmental, behavioral, and social influences. Because some of these factors are different for each person and may change throughout life, the eligibility of an individual for cancer screening may also change over time. The decision of whether someone should receive cancer screening is different for each person.

Researchers are also continually evaluating accruing evidence to recommend changes to existing eligibility criteria to screen for different types of cancer. For example, studies have found that even if all those who are eligible for lung cancer screening under the current USPSTF-recommended guidelines were to undergo screening, a large proportion of lung cancers will still be missed (282)Osarogiagbon RU, et al. (2023) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 43: e389958. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One study of nearly 2000 patients with lung cancer found that only 54 percent of patients would have been deemed eligible for screening under the current USPSTF recommendations (283)Osarogiagbon RU, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2094. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As more evidence accumulates indicating that existing recommendations need to be revised, USPSTF and other cancer-focused organizations reevaluate existing screening recommendations and make evidence-based adjustments.

It is important that people empower themselves with the most up-to-date information on cancer screening eligibility by having an ongoing dialogue with their health care providers and develop a personalized cancer screening plan that considers their specific risks and tolerance of potential harms from screening tests.

Those at an Average Risk of Being Diagnosed with Cancer

Individuals at average risk of being diagnosed with cancer are those who do not have a family history of cancer or personal history of cancer, and do not have an inherited genetic condition that places them at a higher risk of developing cancer. Two key considerations for recommending screening in average-risk individuals are gender and age. USPSTF recommends that average-risk individuals should receive routine screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer when they reach the eligible age (Grades A and/or B recommendations). For prostate cancer screening, USPSTF recommends that average-risk individuals should have an ongoing dialogue with their health care provider to make an informed and shared decision, when they reach the eligible age (Grade C) (see Sidebar 21).

The probability of developing cancer increases with advanced age. According to the most recent estimates, 88 percent of people diagnosed with cancer in the U.S. are 50 or older (28)American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . Therefore, researchers continually evaluate, among other factors, the optimal age for starting or stopping cancer screening, and expert panels, such as USPSTF, periodically update guidelines based on the new evidence.

As one example, in May 2023, USPSTF proposed reducing the recommended starting age of screening from 50 to 40 for women who are at an average risk of developing breast cancer. Researchers estimate that the new guidance could save 19 percent more lives from breast cancer (284)United States Preventive Services Taskforce. Draft Recommendation: Breast Cancer: Screening. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . People should discuss cancer screening during routine consultations with their health care providers, and evaluate their cancer screening plans according to the most up-to-date information.

Those at a Higher-Than-Average Risk of Being Diagnosed with Cancer

Individuals at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer are those who have a strong family history of cancer, a personal history of cancer, certain tissue makeup, an inherited genetic condition, or are exposed to one or more cancer risk factors, all of which place them at a higher risk of developing cancer. One example is individuals who consume tobacco products. According to CDC, people who smoke cigarettes are 15 to 30 times more likely to develop lung cancer or die from it than people who do not smoke.

Women with extremely dense breast tissue are considered at higher-than-average risk of developing breast cancer compared to women with less dense breast tissue. Because of gaps in the current knowledge, USPSTF does not recommend additional screening tests for women with extremely dense breasts in the recently released draft statement of the revised recommendations for breast cancer screening (284)United States Preventive Services Taskforce. Draft Recommendation: Breast Cancer: Screening. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . However, other cancer-focused organizations do recommend additional screening tests for women with dense breast tissue (285)Monticciolo DL, et al. (2018) J Am Coll Radiol. 15: 408. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, 38 U.S. states currently require some level of breast density-related notification after a mammogram, and many provide expanded insurance coverage for additional screening for those who have dense breast tissue (286)Densebreast-info.org. Dense Breast Reporting and Screening Coverage: State Law Map. Accessed: July 31, 2023. .

It is important to note that extremely dense breast tissue is only one of many risk factors for breast cancer. More research is necessary to determine why women with dense breast tissue are at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer and whether this knowledge can be used to improve risk prediction models for breast cancer.

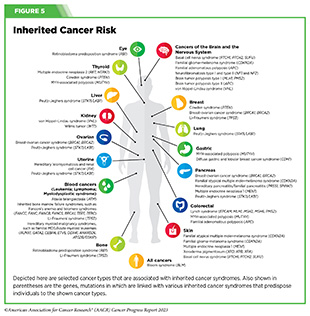

Another group of individuals at higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer is people with inherited cancer susceptibility syndromes (or hereditary cancer syndromes), which are caused by genetic mutations that can be passed on from one generation to the next and can predispose an individual to develop certain types of cancer (see Figure 5). For example, individuals who have Lynch syndrome, which is caused by mutations in genes important for repairing damaged DNA, have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, and many other types of cancer. USPSTF recommends that individuals with a personal or family history of Lynch syndrome should speak with their health care providers about appropriate screening options (288)Davidson KW, et al. (2021) JAMA, 325: 1965. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

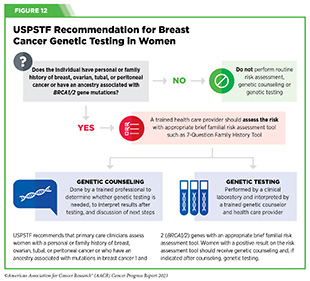

Individuals who consider themselves at a high risk for an inherited cancer-predisposing genetic mutation should, in consultation with their health care providers, also consider genetic counseling and testing. Expert panels sometimes issue guidelines for genetic counseling and testing. For example, in 2019, USPSTF issued recommendations for breast cancer risk assessment, genetic counseling and genetic testing for women with a personal or family history of breast, ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer or an ancestry associated with BRCA1/2 gene mutation (see Figure 12) (289)Owens DK, et al. (2019) JAMA, 322: 652. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

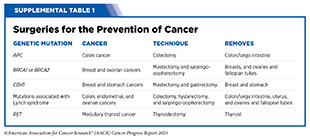

Genetic testing may aid individuals and their health care teams in deciding whether, increased frequency of breast cancer screening with MRI, preventive surgery (see Supplemental Table 1), or chemoprevention (e.g., use of selective estrogen receptor modulators) would help reduce the risk of developing cancer later on in life. It is concerning that only 6.8 percent of more than 1.3 million people had undergone genetic testing, according to a recent study examining the extent of germline mutations among people diagnosed with cancer (290)Kurian AW, et al. (2023) JAMA, 330: 43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is imperative that individuals who are at a high risk for being diagnosed with cancer because of inherited mutations consult with their care team for whether or when they should undergo genetic testing.

Suboptimal Uptake of Cancer Screening

Evidence shows that adherence to recommended cancer screening saves lives (see Importance of Cancer Screening). In a recent study, researchers found that 80 percent of the study participants who received a diagnosis of lung cancer at an early stage via routine lung cancer screening were living 20 years after the initial diagnosis (291)Radiological Society of North America. 20-year Lung Cancer Survival Rates in the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (IELCAP). Accessed: July 5, 2023. . Despite the benefit of lung cancer screening, unfortunately, only six percent of U.S. individuals eligible for lung cancer screening were up to date with the recommended screening in 2022 (236)American Lung Association. State of the Air 2023. Accessed: July 5, 2023. .

It is equally important to know when an individual should stop screening for cancer. USPSTF recommendations include the age past which the potential harms from screening tests are likely to outweigh benefits (see Sidebar 20). For example, USPSTF guidelines recommend against screening for prostate cancer in men older than 69. However, a recent study found that 55.3 percent of men ages 70 to 74, 52.1 percent of men ages 75 to 79, and 39.4 percent of men age 80 and older were screened for prostate cancer in 2020 (292)Kalavacherla S, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e237504. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Suboptimal adherence to recommended cancer screening guidelines is evident across cancer types, and researchers are continually working to develop evidence-based approaches to increase adherence to cancer screening guidelines (see Progress Toward Increasing Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines). The COVID-19 pandemic has further adversely impacted cancer screening rates (293)Star J, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32:879. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent study evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer screening found that, in the United States between 2019 and 2021, screening within a prior year decreased from 60 percent to 57 percent for breast cancer, from 45 percent to 39 percent for cervical cancer, and from 39.5 percent to 36 percent for prostate cancer (259)Chiang KV, et al. (2021) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 70: 769. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

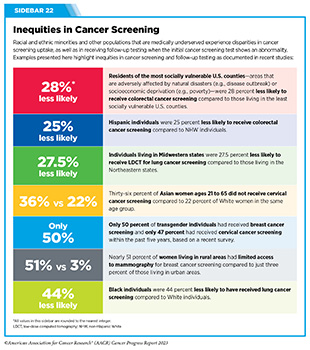

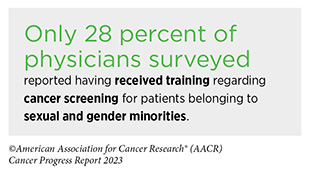

Another area of major concern is the inequities in cancer screening and follow-up testing among certain U.S. population groups (see Sidebar 2). For example, compared to the overall U.S. population, cancer screening rates are lower among certain racial and ethnic as well as sexual and gender minorities (see Sidebar 22) (293)Star J, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32:879. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A multitude of barriers contribute to low screening rates, including social and structural barriers; bias and discrimination against minorities in the health care system; mistrust of health care professionals among minorities; lack of access to quality health insurance and coverage; low health literacy; and miscommunication between patients and providers (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2023. .

It is important to fully understand why individuals belonging to certain population groups are at a higher risk of being diagnosed with certain types of cancer, and whether suboptimal uptake of screening contributes to this higher risk. Furthermore, there is an urgent need to collect disaggregated data related to all aspects of cancer burden and clinical care from individuals belonging to racial and ethnic minorities, sexual and gender minorities, and others who are socially and economically disadvantaged, including people who belong to more than one of these populations, as detailed in the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022 (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2023. . Evidence gathered from such data will help with developing cancer care guidelines and interventions to improve care delivery that is tailored to specific populations, which may lead to health equity for all.

Progress Toward Increasing Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines

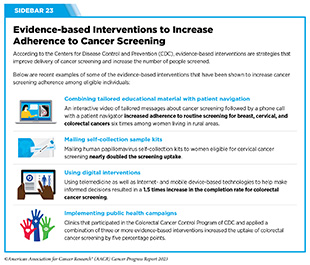

Multilevel and multipronged approaches are required to eliminate cancer health inequities across the continuum of care, including uptake and follow-up of recommended evidence-based cancer screening among all eligible individuals (see Sidebar 23). Stakeholders across the cancer care continuum (see Sidebar 1) are working together to achieve these goals.

In the United States, the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF), established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 1996 at CDC, develops guidance on community-based health promotion and disease prevention. Based on the available scientific evidence, CPSTF periodically issues recommendations and findings on public health interventions designed to improve health and safety. As one example, CPSTF recently reviewed 34 studies evaluating the effectiveness of patient navigation in increasing cancer screening uptake among racial and ethnic minority populations and people with lower incomes (303)The Community Guide. TFFRS: Patient Navigation Services to Increase Cancer Screenings | The Community Guide. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . Based on the findings, CPSTF recommended in the 2022 Annual Report to Congress that patient navigation services should be provided to medically underserved communities to increase breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening (304)Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2022 Annual Report to Congress. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . The Task Force concluded that patient navigation services advance health equity. Patient navigation also improves timely and appropriate follow-up care and treatment, and may improve health and reduce cancer-related disparities for the racial and ethnic populations and people with lower incomes who are medically underserved.

Recognizing the critical importance of regular cancer screening in saving lives, the National Cancer Plan, released by NCI in April 2023, prioritizes early cancer detection and cancer prevention (309)National Cancer Institute. National Cancer Plan. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . The plan calls for new technologies and methods to detect cancers early, especially cancers for which no screening tests exist currently (such as cancers of the liver and pancreas), and to eliminate precancerous lesions before they become cancerous while minimizing side effects.

New Frontiers in Cancer Screening

Researchers are working on novel methods and strategies that may improve detection of early cancers and/or precancerous lesions to reduce the death rate from cancer, while minimizing any potential harm from the procedure. Two areas of research with exciting new developments are the use of artificial intelligence and blood-based tests to detect cancer early.

Realizing the Potential of Artificial Intelligence for Early Detection of Cancers

There have been unprecedented advances in recent years in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in medicine, including for cancer detection. One of the several ways researchers are using AI and ML for cancer detection is in analyzing large amounts of imaging data collected for the purposes of cancer screening to recognize patterns that are otherwise time-consuming and difficult to discern by eye even by trained health care professionals (see Sidebar 24).

A recent study found that AI-assisted colonoscopy detected 21 percent more polyps (clumps of usually benign cells that build up on the lining of the colon and can be precursors to colon cancer) compared to a conventional expert-directed colonoscopy (310)Xu H, et al. (2023) Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 21: 337. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study described the development of a deep learning model that can predict future risk of developing lung cancer within the next one to six years following a single LDCT scan (311)Mikhael PG, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 2191. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is important to note that applying AI in medicine is an area of active research and not all studies have found AI-assisted improvements in cancer detection (312)Levy I, et al. (2022) Am J Gastroenterol, 117: 1871. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additional research is needed to understand the benefit of AI-driven applications in cancer medicine and whether AI mitigates or worsens health disparities.

Some of the AI-driven medical devices and software have proven to be highly accurate in clinical trials when compared to current standard practices. In recent years, the number of FDA-approved AI-enhanced software systems for use in medicine, including early detection, has increased significantly (315)U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . Here, we are using two recent examples—ProstatID and SKOUT—to highlight the progress in this exciting area of cancer research.

In July 2022, FDA approved ProstatID, which uses AI to measure the volume of the prostate gland from scans obtained using traditional MRI and detect suspicious cancerous lesions. ProstatID is approved for use in a health care facility or hospital to assist trained radiologists in the detection and characterization of potentially cancerous lesions using MRI data. The approval was, in part, based on two clinical studies showing improved detection of prostate cancer and fewer false positives when radiologists used ProstatID.

In September 2022, FDA approved SKOUT, a medical device that uses advanced computer vision technology designed to recognize polyps and suspicious tissue and provide real-time feedback to clinicians during colonoscopy. The approval was based on results from a large clinical study showing that detection of polyps and suspicious lesions was substantially improved when colonoscopy was aided with SKOUT compared to standard colonoscopy without the aid of SKOUT (719 versus 562 detections, respectively). The improved detection was even more pronounced for smaller polyps (44 percent increase when using SKOUT versus 29 percent increase when using standard colonoscopy) (313)Shaukat A, et al. (2022) Gastroenterology, 163: 732. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Examples of recent FDA approvals discussed here underscore the potential applications of AI in the clinic to aid early detection and diagnostic purposes. Uses of AI in other aspects of cancer care—genomic characterization of tumors, drug discovery, and improved cancer surveillance—are also active areas of research (see Artificial Intelligence) (316)Iqbal MJ, et al. (2021) Cancer Cell Int, 21: 270. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Moving Toward Minimally Invasive Cancer Screening

Most cancer screening tests in current use are designed to detect only one type of cancer. Some of the tests are invasive medical procedures, with potential health risks (see Sidebar 19). Researchers are actively working to develop ways to detect cancer using tests that are less invasive and safer. Liquid biopsy is one such way in which a sample of blood, urine, or other body fluid is used to look for signs of cancer.

Thanks to research, the knowledge that precancerous lesions and tumors shed a variety of materials (such as cancer cells and small pieces of DNA, RNA, or proteins) has led to the development of tests that can detect these materials in blood, urine, or other body fluids. Liquid biopsy approaches are already in routine use for making treatment decisions and/or monitoring if cancer has returned in patients who have already received cancer treatment, and can be especially beneficial for pediatric patients with cancer (317)Connal S, et al. (2023) J Transl Med, 21: 118. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](318)Christodoulou E, et al. (2023) NPJ Precis Oncol, 7: 21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Liquid biopsy procedures can detect abnormal cells and/or other materials from tumors that are circulating in the blood. It is critical that liquid biopsy tests are highly specific in detecting cancer-derived changes that are absent in healthy cells before these tests can be recommended for cancer screening in the general population (319)Doubeni CA, et al. (2023) Am Fam Physician, 107: 224. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Ongoing efforts are focused on developing strategies to ensure that liquid biopsy tests are specific in detecting cancer(s) without compromising sensitivity of the test (320)Doubeni CA, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128 Suppl 4: 883. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

An exciting aspect of liquid biopsy tests is the possibility of screening for many cancer types simultaneously and potentially with high specificity. If these procedures, called multicancer detection (MCDs) assays or multicancer early detection tests, are found to be effective, they may make receiving cancer screening easier for individuals. These tests may also decrease potential physical harm(s) from some of the conventional cancer screening tests, such as colonoscopy. Furthermore, a minimally invasive test that can be used to screen for multiple cancer types could transform early detection of cancers; potentially increase participation in cancer screening; and may decrease some current barriers to cancer screening.

An ongoing study is evaluating the specificity and accuracy of an MCD test for more than 50 types of cancer. Findings thus far show that the test correctly identified two out of every three cancers in more than 5,000 people who had visited their health care providers with suspected symptoms. The test also correctly identified the site from which cancer originated in 85 percent of those cases (321)Oxford Cancer. SYMPLIFY. Accessed: July 5, 2023. . A recent modeling study using the cancer mortality data from England estimated that using MCDs would result in 17 percent fewer deaths from cancer per year (322)Sasieni P, et al. (2023) Br J Cancer, 129: 72. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

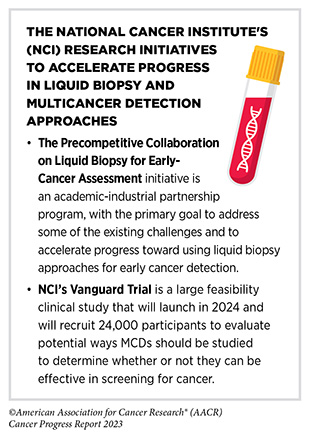

It is important to note that the research evaluating the safety and efficacy of MCD tests for routine cancer screening is at an early stage. While the initial studies are encouraging, currently there are limited data from prospective clinical studies (319)Doubeni CA, et al. (2023) Am Fam Physician, 107: 224. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](320)Doubeni CA, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128 Suppl 4: 883. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Key issues that remain unresolved include whether MCD tests can detect early stages of multiple cancer types accurately; what will be the rate of false positive results; whether using an MCD test will provide benefits that outweigh potential harms; and how much these tests will cost. Large ongoing studies, such as NCI’s Vanguard Trial, will answer some of these critically important questions.

Next Section: Advancing the Frontiers of Cancer Science and Medicine Previous Section: Reducing the Risk of Cancer Development