- Purpose of Routine Cancer Screening

- Development of Cancer Screening Guidelines

- Recent Advances in Cancer Screening and Early Detection

- Harnessing the Power of Artificial Intelligence for Early Detection of Cancers

- Mapping a Course for Cancer Detection at the Earliest Possible Stage

- Moving Toward Minimally Invasive Cancer Testing

- Factors That Determine Whether Individuals Should Receive Cancer Screening

- Suboptimal Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines

- Progress Toward Increasing Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines

Screening for Early Detection

In this section, you will learn:

- Breakthroughs in understanding of cancer initiation and progression are facilitating the development of cancer screening tests that can detect cancer at its earliest stage before it has spread to other sites.

- Authoritative professional organizations and government-affiliated agencies carefully evaluate the benefits and harms of cancer screening tests to make evidence-based recommendations for their use in the clinic.

- Technological advances, as highlighted by FDA approvals of software systems driven by artificial intelligence to aid cancer early detection and diagnosis, are poised to transform cancer screening in the coming years.

- There are substantial opportunities to save lives by developing evidence-based early detection of cancer types with high mortality rates, such as cancers of ovary, pancreas, and liver, for which there are currently no recommended screening tests available for the average-risk population.

In recent decades, researchers have made major progress in understanding the underlying causes of cancer development (see Understanding How Cancer Develops). In parallel, technological innovations in DNA sequencing, cellular imaging, and collection and storage of biospecimens have enabled reliable and reproducible detection of the genetic, molecular, and cellular events that drive cancer initiation and progression. Collectively, these advances have accelerated the development of screening tests and examinations that can find precancerous lesions or cancers at the earliest stage of development when it is easier to treat them successfully.

Purpose of Routine Cancer Screening

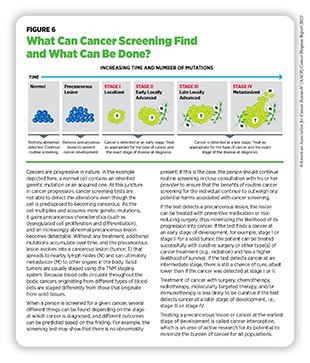

Cancer screening is the evidence-based determination of whether a person has precancerous lesions or cancer before any signs or symptoms of the disease appear. While modifying certain behaviors can reduce the risk of developing cancer, routine screening for cancer can help find an aberration at the earliest possible time during cancer development. Health care providers use the information gleaned from a cancer screening test to make an informed decision on whether to monitor or treat, or surgically remove precancerous lesions or early-stage cancer before either progresses to a more advanced stage (see Figure 6).

There are different kinds of cancer screening tests that include laboratory tests to determine the changes in cancer biomarkers in samples of tissues or fluids in the body and imaging procedures to look for abnormalities inside the body (see sidebar on Ways to Screen for Cancer). In addition, clinicians may also determine whether an individual needs to be screened for certain types of cancer using visual examination to check for unusual features such as lumps or discolored skin and/or reviewing the medical and family histories to evaluate an individual’s inherited, behavioral, and environmental risks of developing cancer.

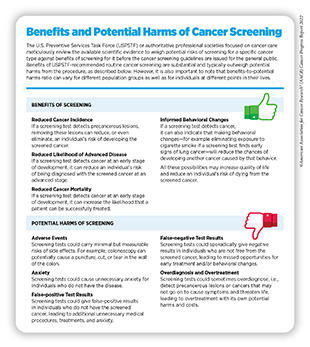

Detection of cancers through routine screening saves lives and improves quality of life by catching the disease early and treating it, and minimizing the risk of cancer progressing to an advanced, harder-to-treat stage (247)Crosby D, et al. Early detection of cancer. Science 2022;375:eaay9040. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In 2020, findings from a landmark clinical trial evaluating the benefits of lung cancer screening showed a 25 percent decline in lung cancer deaths at a 10-year follow-up of more than 6,000 participants who underwent lung cancer screening from December 2003 to July 2006 (248)de Koning HJ, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med 2020;382:503-13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent study examined the impact of lung cancer screening guidelines issued in 2013 by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and compared it with that of the 2021 revised guidelines. According to the study’s findings, an estimated 6,845 and 23,444 additional lives would be saved from lung cancer if 30 percent and 100 percent of the population eligible under the revised guidelines were screened, respectively (249)Meza R, et al. Impact of Joint Lung Cancer Screening and Cessation Interventions Under the New Recommendations of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. J Thorac Oncol 2022;17:160-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another recent study found that increasing the current levels of screening for breast, colorectal and cervical cancers to 100 percent will collectively save more than 45,000 lives (250)Sharma KP, et al. Preventing Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Deaths: Assessing the Impact of Increased Screening. Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17:E123. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, it is important to note that some screening tests are invasive medical procedures that can potentially cause harm (see sidebar on Benefits and Potential Harms of Cancer Screening). Because of the potential harms, the risks and benefits of cancer screening are carefully considered for everyone.

Development of Cancer Screening Guidelines

The overarching goal of cancer screening is to reduce the burden of cancer in the general population. The key objective is to help individuals and their health care providers decide together whether an individual should be screened for cancer, at what age the screening should start and stop, and how frequently the screening should be done and by which method.

When developing cancer screening guidelines for the general population (i.e., those who are at an average risk of developing cancer), authoritative groups of subject matter experts consider age as well as several aspects that are specific to individuals or population groups for whom the screening guidelines are being developed. These considerations include whether or not a person has a particular organ (e.g., for cervical cancer screening, whether an individual never had a cervix or had a hysterectomy with cervix removal); has a smoking history (for lung cancer screening); has an all-negative prior screening history (for cervical cancer screening); has reduced life expectancy (for prostate cancer screening); has a family history (for colorectal and breast cancer screening); and/or belongs to a racial or ethnic minority group (for prostate cancer screening).

In the U.S., guidelines for cancer screening are meticulously developed by multiple authoritative groups and professional societies. For example, an independent group of experts convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services carefully evaluates data regarding the benefits and potential harms of different approaches to disease prevention, including cancer screening tests, genetic testing, and preventive therapeutics, to make evidence-based recommendations about the use of these in primary care settings. These volunteer experts form USPSTF (see sidebar on How Are Cancer Screening Guidelines Developed?).

USPSTF recommendations for cancer screening tests fall into four categories, including recommendations for screening certain individuals at certain intervals (see sidebars on USPSTF Guidelines for Screening Five Cancer Types and Differential Risks That Guide Cancer Screening Decisions), recommendations against screening, and deciding that there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. In addition to considering evidence regarding potential new screening programs, USPSTF reevaluates existing recommendations as new research becomes available and can revise the recommendations if necessary (see sidebar on How Are Cancer Screening Guidelines Developed?). Occasionally, other professional societies focused on cancer care also issue screening guidelines.

Recent Advances in Cancer Screening and Early Detection

Characterization of molecular and cellular features that can help detect precancers or cancers at the earliest possible stage when it is easier to treat them successfully are areas of active research. In addition, researchers are working on developing novel strategies that can improve the efficacy, efficiency, and accuracy of cancer screening exams, while minimizing any potential harm from the procedure. Another area of ongoing research is to develop tools and tests that detect only those cancers that are most likely to progress to an advanced, aggressive stage.

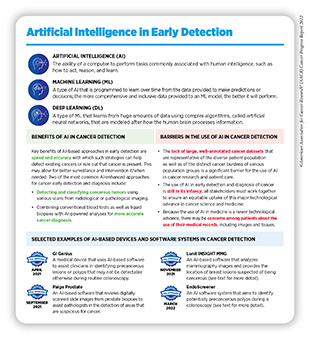

Harnessing the Power of Artificial Intelligence for Early Detection of Cancers

One area of intense research and rapid progress in recent years has been the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to analyze large amounts of imaging data collected for the purposes of cancer screening and to recognize patterns that are otherwise time-consuming and difficult to discern by eye even by trained experts (see sidebar on Artificial Intelligence in Early Detection). As one example, researchers developed an AI-enhanced model that used images from a person’s mammograms to predict that person’s likelihood of developing breast cancer in the next five years. The model’s prediction was more accurate than currently available tools to assess a person’s risk of developing breast cancer (252)Yala A, et al. Toward robust mammography-based models for breast cancer risk. Sci Transl Med 2021;13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Although additional research is needed, some of the AI-driven medical devices and software have proven to be highly accurate and effective in clinical trials. From August 1, 2021, to July 31, 2022, the 12 months covered by this report, FDA approved many AI-enhanced software systems for assisting clinicians in detecting cancers early. Here, we are using examples of two such software systems—Lunit INSIGHT MMG and EndoScreener—to highlight the rapid advancement in this exciting area of cancer research.

In November 2021, FDA approved Lunit INSIGHT MMG, an AI-driven software that uses deep learning to analyze mammography images with high accuracy for detecting breast cancer (see sidebar on Artificial Intelligence in Early Detection). Lunit INSIGHT MMG provides the location of lesions that could indicate breast cancer and assigns an abnormality score that reflects the software’s confidence of the existence of lesions. The software was developed and validated using 170,230 mammography examinations, of which 36,468 were of breast cancer as confirmed by tissue biopsy. Researchers found that, compared to manual evaluation of mammograms by pathologists, the software was 12 percentage points more sensitive in detecting cancers with mass, and 40 percentage points more sensitive in detecting cancers that were asymmetrical or distorted in slide images (255)Kim HE, et al. Changes in cancer detection and false-positive recall in mammography using artificial intelligence: a retrospective, multireader study. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e138-e48. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study compared the diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity of Lunit INSIGHT MMG with two commercially available AI-based software systems for the detection of breast cancer. Researchers subjected 8,805 mammograms, of which 739 had breast cancer diagnosis, to the analysis and found that Lunit INSIGHT MMG had 15 percent higher sensitivity compared to the other two algorithms (256)Salim M, et al. External Evaluation of 3 Commercial Artificial Intelligence Algorithms for Independent Assessment of Screening Mammograms. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1581-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

In March 2022, FDA approved EndoScreener, an artificial intelligence software system that aims to identify potentially precancerous polyps during a colonoscopy. Polyps are clumps of usually benign cells that build up on the lining of the colon and can be precursors to colon cancer. The approval was based on findings of a clinical study reporting that EndoScreener detected about 32 percent more polyps than manual observation alone, decreasing the rates of missed polyps during colonoscopy to 20 percent from 31 percent using standard methods (257)Glissen Brown JR, et al. Deep Learning Computer-aided Polyp Detection Reduces Adenoma Miss Rate: A United States Multi-center Randomized Tandem Colonoscopy Study (CADeT-CS Trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:1499-507 e4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](258)Cheng CL, et al. Comparison of Right Colon Adenoma Miss Rates Between Water Exchange and Carbon Dioxide Insufflation: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2021;55:869-75. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Research has found that, during colonoscopy, about one third of precancerous lesions can go undetected, potentially delaying treatment for colorectal cancer (259)Ahn SB, et al. The Miss Rate for Colorectal Adenoma Determined by Quality-Adjusted, Back-to-Back Colonoscopies. Gut Liver 2012;6:64-70. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Approval of EndoScreener is expected to substantially improve detection of precancerous lesions during colonoscopy (259)Ahn SB, et al. The Miss Rate for Colorectal Adenoma Determined by Quality-Adjusted, Back-to-Back Colonoscopies. Gut Liver 2012;6:64-70. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Selected approvals discussed here underscore the rapid advances in routine use of AI in the clinic for early detection and diagnostic purposes. Use of AI in other aspects of cancer research and patient care—genomic characterization of tumors; drug discovery; and improved cancer surveillance—is an active area of investigation (see Artificial Intelligence) (260)Iqbal MJ, et al. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in cancer diagnosis: looking into the future. Cancer Cell Int 2021;21:270. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Mapping a Course for Cancer Detection at the Earliest Possible Stage

It can take decades for normal cells to turn cancerous from the first genetic and/or epigenetic alterations. During this time, cells can remain in a precancerous state, sometimes evading detection by the immune system and on their way to becoming malignant.

One of the ongoing initiatives to characterize the precancerous state is the Human Tumor Atlas Network (HTAN). Launched in September 2018, HTAN is an NCI-funded Cancer Moonshot initiative through which a collaborative network of Research Centers and a central Data Coordinating Center is working to identify the molecular and cellular events that cause healthy cells to become precancerous and cancerous. Some of the cancers for which HTAN is developing the so-called “precancerous atlases” include cancers of the lung, pancreas and breast (261)National Cancer Insititute. Human Tumor Atlas Network. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

In-depth knowledge of the precancerous state can offer an opportunity not only to detect cancer at the earliest possible stage, but also to intervene before a cell becomes cancerous, a concept called cancer interception.

Moving Toward Minimally Invasive Cancer Testing

Some of the tests used for cancer screening are invasive medical procedures, with potential health risks. Furthermore, most cancer screening tests are designed to detect only one type of cancer. Research has revealed that precancerous lesions and tumors shed a variety of cellular material, such as cells, microscopic lipid vesicles called exosomes, and/or cell-free DNA, RNA, or proteins. Any of these materials can be detected in blood or other body fluids, such as urine, using a minimally invasive procedure called liquid biopsy. Liquid biopsy approaches are in routine use for analyzing tumor-associated genetic alterations using circulating tumor DNA, and for making treatment decisions and/or monitoring for signs of cancer’s return in those individuals who have already received cancer treatment. Researchers are developing early detection tests that are minimally invasive and can screen for many cancer types simultaneously, thus making it easier for individuals being screened. These tests will also likely decrease potential harm(s) from conventional cancer screening tests to individuals being screened.

As one example, in a recent study of 2,094 patients, researchers combined liquid biopsy to detect multiple cancers using a small amount of a patient’s serum with machine learning to differentiate cancer from noncancer samples. Findings of the study reported that the test was able to accurately detect eight types of cancer at various stages of development with nearly 90 percent sensitivity and 61 percent specificity (263)Cameron JM, et al. Multi-cancer early detection with a spectroscopic liquid biopsy platform. Research Square Platform LLC; 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This and other similar studies underscore the immense promise of multicancer early detection tests, but additional research is needed before they can be routinely used in the clinic.

A minimally invasive test that can be used to screen for multiple cancer types reliably can revolutionize early detection of cancers by minimizing harm for the individual being screened; by potentially increasing adherence to routine cancer screening; and by potentially decreasing the financial and logistic barriers to cancer screening.

Factors That Determine Whether Individuals Should Receive Cancer Screening

A person’s risk of developing cancer is determined by many factors including inherited, environmental, and lifestyle influences, some of which may change throughout life. Thus, the decision of whether someone should be screened for cancer, at what age, and for which cancer type(s) is different for each person and may change over the course of their lives (see sidebar on Differential Risks That Guide Cancer Screening Decisions). It is important that people consult with their health care providers to develop a personalized cancer screening plan that considers their risk of developing a cancer and their tolerance for the potential harms of a screening test.

Suboptimal Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines

Suboptimal adherence to cancer screening guidelines means when an eligible individual is not up to date with routine cancer screening as recommended by USPSTF guidelines, or when an individual for whom the routine cancer screening is no longer recommended continues to receive it. Despite the many benefits of routine cancer screening, underscreening— the underuse of routine cancer screening among eligible individuals—is common. As one example, only 67 percent of adults who were eligible for routine colorectal cancer screening in 2018 were up to date with routine screening (264)Sabatino SA, et al. Cancer Screening Test Receipt – United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:29-35. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. One recent study estimated that increasing the use of screening for colorectal cancer alone from 67.7 percent (levels of colorectal cancer screening in 2016, the data year of the study) to 100 percent could have prevented an additional 35,530 deaths over the lifetime of an adult age 50 (250)Sharma KP, et al. Preventing Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Deaths: Assessing the Impact of Increased Screening. Prev Chronic Dis 2020;17:E123. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], underscoring the importance of cancer screening in early detection and its potential in saving lives.

While being up to date with routine cancer screening guidelines is key to early detection, it is also important to know when an individual should stop screening for cancer. USPSTF guidelines include the age past which the potential harms from screening tests are likely to outweigh a net benefit (see sidebar on USPSTF Guidelines for Screening Five Cancer Types). However, overscreening, e.g., the use of screening tests beyond the recommended age, is common. As one example, researchers found that at least half of older U.S. adults in 2018 had received at least one unnecessary screening test for breast, cervical, or colorectal cancer in the past few years (265)Moss JL, et al. Geographic Variation in Overscreening for Colorectal, Cervical, and Breast Cancer Among Older Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2011645. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is also evidence that continuing cancer screening beyond the recommended age may be beneficial for some older adults (266)Brawley OW. On Breast Cancer Screening in Older Women. Ann Intern Med 2022;175:127-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is of utmost importance that older adults make an informed and shared decision with their provider whether to continue screening for cancer that is tailored to their health status and life expectancy, as well as to their specific exposure to genetic, environmental, and and modifiable risk factors (267)Kotwal AA, et al. Cancer Screening Among Older Adults: a Geriatrician’s Perspective on Breast, Cervical, Colon, Prostate, and Lung Cancer Screening. Curr Oncol Rep 2020;22:108. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](268)Schoenborn NL, et al. Racial disparities vary by patient life expectancy in screening for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:3389-91. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](269)Schoenborn NL, et al. Preferred clinician communication about stopping cancer screening among older us adults: Results from a national survey. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1126-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

As highlighted in the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022, released in June 2022, cancer screening rates are substantially lower among those from racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Furthermore, screening patterns vary for different types of cancer and/or screening tests (270)Kaiser Family Foundation. Racial disparities in cancer outcomes, screening, and treatment. Accessed: July 15, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Barriers such as access to health insurance, low health literacy, and miscommunication between patients and providers contribute to low screening rates (271)Liu D, et al. Interventions to reduce healthcare disparities in cancer screening among minority adults: A systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2021;8:107-26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

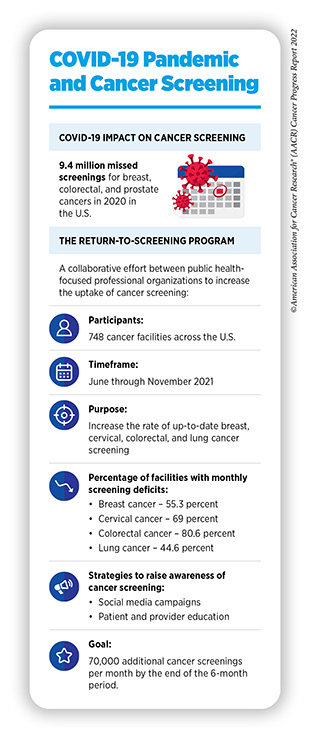

As detailed in the AACR Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Research and Patient Care, released in February 2022, severe interruptions in routine cancer screening, especially during the initial months of the pandemic, may have exacerbated the existing disparities in cancer screening (8)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Research and Patient Care. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Screening rates for all five cancers declined significantly during the peaks of COVID-19, although more recent data indicate that screening rates for some cancer types are returning to prepandemic levels. Furthermore, professional organizations are teaming up to help increase the uptake of cancer screening that has been impacted by the pandemic (see sidebar on COVID-19 Pandemic and Cancer Screening).

Here, we focus our discussion on the disparities in screening for five cancer types for which USPSTF currently has population-based screening guidelines and discuss some of the interventions that have helped close the disparity gap in cancer screening.

Unfortunately, not all segments of the U.S. population benefit equitably from routine cancer screening (see sidebar on Disparities in Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines). The reasons for disparities in cancer screening are multifactorial and include lack of access to health care; reduced rate of follow-up if the initial screening test indicates that cancer may be present; fear of cost; lack of health literacy about the benefits and potential harms of cancer screening; distrust in the health care system; and/or miscommunications between patient and provider (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Another research area in cancer screening that requires immediate attention from all stakeholders is the disparities in routine cancer screening among SGM populations, especially among transgender individuals. A recent study reported that, compared to cisgender individuals, only 32 percent of individuals transitioning from female to male had undergone breast cancer screening; these individuals were also 58 percent less likely to adhere to cervical cancer screening (282)Oladeru OT, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities in transgender people. Am J Clin Oncol 2022;45:116-21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These findings highlight the urgent need to develop cancer screening guidelines that are specific to members of the SGM community and to implement culturally and socially sensitive interventions that help improve health care experiences of the SGM community in the U.S.

Progress Toward Increasing Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines

Eliminating inequities in cancer screening and increasing the uptake of routine cancer screening among eligible individuals require multilevel and multipronged approaches to achieve equitable access and optimal adherence to cancer screening. These approaches include dismantling structural racism, discrimination, and other societal inequities that pose significant barriers in access to cancer screening; raising the awareness of cancer screening among eligible individuals, especially those belonging to racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations; effectively communicating benefits and potential harms of cancer screening; developing culturally tailored interventions that address the lack of health literacy and cancer screening knowledge among certain populations; making cancer screening accessible and convenient to all— both in availability and cost; and conveying the importance of follow-up visits if the initial screening exam indicates the possibility of cancer. Stakeholders across the cancer care continuum—cancer researchers, physicians, federal regulatory and funding agencies; cancer-focused professional organizations; patient advocates and navigators—are working together to achieve this goal, and many established as well as innovative interventions are being tested across the nation (see sidebar on Approaches to Increase Adherence to Cancer Screening).

Although approaches discussed in this chapter are raising awareness of the importance of routine cancer screening among eligible individuals, concerted and coordinated efforts by stakeholders across the cancer care continuum are needed to maximize the impact of these strategies in achieving equitable public health. Professional organizations, government agencies, and policy makers focused on public health are advocating for a comprehensive national strategy to increase adherence to screening guidelines (289)National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Guiding cancer control: A path to transformation. Accessed: July 28, 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A key component of such strategies is legislation for easy access to cancer screening as discussed by Congressman Brian Fitzpatrick).

At the federal level, NCI and CDC play important roles in raising awareness for cancer screening. For example, the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) of CDC seeks to increase screening through implementation of some or all four of the CDC-prioritized, evidence-based interventions (patient reminders, provider reminders, reducing structural barriers, provider assessment and feedback) and four optional supporting activities (small media, e.g., videos and brochures, professional development and provider education, patient navigation, and community health workers) (290)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP). Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. To achieve this goal, CDC partners with clinics, hospitals, and other health care organizations to use and strengthen strategies that have been shown to increase screening. A recent evaluation of 355 clinics that partnered with CRCCP across the country showed that >90 percent of the clinics implemented and fully integrated into their health systems at least two of the four evidence-based strategies by the third year of the partnership (291)Maxwell AE, et al. Evaluating uptake of evidence-based interventions in 355 clinics partnering with the colorectal cancer control program, 2015-2018. Prev Chronic Dis 2022;19:E26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Initial findings from the program indicate that the longer the clinics participate in the program the greater the increase from baseline in their CRC screening rates. For example, screening rates increased, on average, by 8.2 percentage points and 12.3 percentage points for clinics that participated in the program for two years and four years, respectively (290)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP). Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The impact of these interventions on increasing colorectal cancer screening among eligible individuals is expected to become even more pronounced in the coming years.

Next Section: Decoding Cancer Complexity. Integrating Science. Transforming Patient Outcomes. Previous Section: Preventing Cancer: Identifying Risk Factors