- Eliminate Tobacco Use

- Maintain a Healthy Weight, Eat a Healthy Diet, and Stay Active

- Limit Alcohol Consumption

- Protect Skin from UV Exposure

- Prevent and Eliminate Infection with Cancer-causing Pathogens

- Reduce Risk of Diabetes

- Be Cognizant of Reproductive and Hormonal Influences

- Limit Exposure to Environmental Risk Factors

Preventing Cancer: Identifying Risk Factors

In this section, you will learn:

- In the United States, four out of 10 cancer cases are associated with preventable risk factors.

- Not using tobacco is one of the most effective ways a person can prevent cancer from developing.

- Nearly 20 percent of U.S. cancer diagnoses are related to excess body weight, alcohol intake, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

- Many cases of skin cancer could be prevented by protecting the skin from ultraviolet radiation from the sun and indoor tanning devices.

- Nearly all cases of cervical cancer, as well as many cases of head and neck and anal cancers, could be prevented by HPV vaccination; many cases of liver cancer could be prevented by HBV vaccination.

- Decades of systemic inequities and social injustices have led to adverse differences in social determinants of health, causing a disproportionately higher burden of cancer risk factors among U.S. racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations.

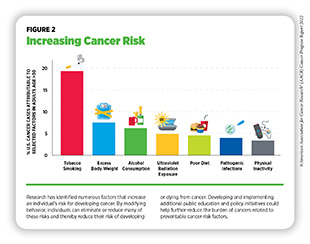

Decades of research have led to the identification of numerous factors that increase the chance of developing cancer (Figure 2). As a result of this work, we know that more than 40 percent of all cancer cases are attributable to preventable causes, including tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity, and obesity (78)Islami F, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition, vaccination against infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) and decreasing exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun and indoor tanning devices can further reduce the burden of certain types of cancer. Identifying additional risk factors to enhance cancer prevention efforts is an area of intensive research (79)Brennan P, et al. Identifying novel causes of cancers to enhance cancer prevention: New strategies are needed. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022;114:353-60. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Cancer risk factors such as tobacco use, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol use are also leading drivers of other chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases, fatty liver disease, and diabetes (80)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). Accessed: July 16, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Therefore, reducing or eliminating exposure to these factors through public education and policy initiative implementation has the potential to lessen the health and economic burden of many other diseases in addition to cancer.

In the United States, many of the greatest reductions in cancer morbidity and mortality have been achieved through the implementation of effective public education and policy initiatives. For example, the 32 percent decline in overall cancer mortality in the U.S. between 1991 and 2019 is largely attributed to reductions in smoking and advances in early detection for some cancers (1)Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:7-33. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](81)Islami F, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, Part 1: National cancer statistics. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2021;113:1648-69. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Despite these advances, the prevalence of some of the major cancer risk factors continues to be high, particularly among segments of the U.S. population that experience cancer health disparities, such as racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations, as discussed in depth in the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022 (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Disparities in the prevalence of preventable cancer risk factors stem from long-standing inequities in numerous social determinants of health among socioeconomically and geographically disadvantaged populations. Lifestyles, behaviors, and exposures are strongly influenced by living environments. For example, lack of quality housing (e.g., housing without smoke-free policies) may expose habitants to high levels of secondhand smoke, a known cause of lung cancer. Moreover, socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are often located in food deserts where there is reduced availability of healthy food options and an abundance of unhealthy, calorie dense, nutrient poor fast food, as well as limited outdoor space for recreation and/or exercise. These living environments create barriers to behaviors that are important in lowering cancer risk. It is imperative that all sectors work together to identify more effective strategies for reducing these barriers to healthy behaviors, disseminating our current knowledge of cancer prevention, and implementing evidence-based interventions to reduce the burden of cancer risks for everyone.

Eliminate Tobacco Use

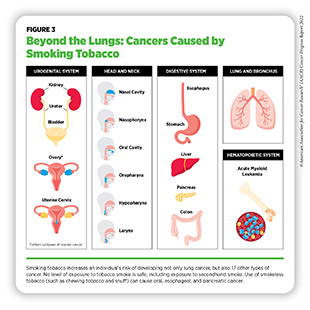

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer. Smoking is associated with the development of 17 different types of cancer in addition to lung cancer (see Figure 3), because it exposes individuals to many harmful chemicals that cause cellular and molecular alterations leading to cancer development (82)Vaz M, et al. Chronic cigarette smoke-induced epigenomic changes precede sensitization of bronchial epithelial cells to single-step transformation by KRAS mutations. Cancer Cell 2017;32:360-76 e6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](83)American Lung Association. State of the Air 2022. Accessed: July 13, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. According to a recent analysis, adults who currently smoke have a three times greater risk of dying from cancer compared to those who do not smoke (84)Thomson B, et al. Association of smoking initiation and cessation across the life course and cancer mortality: Prospective study of 410000 US adults. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1901-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Fortunately, smoking cessation at any age reduces the risk of cancer occurrence and cancer-related death (84)Thomson B, et al. Association of smoking initiation and cessation across the life course and cancer mortality: Prospective study of 410000 US adults. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1901-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition, smoking cessation reduces risk for many adverse health effects beyond cancer, including cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (85)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General. Accessed:[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Thus, one of the most effective ways a person can lower the possibility of developing cancer and other smoking-related conditions is to avoid or eliminate tobacco use.

Thanks to the implementation of nationwide comprehensive tobacco control initiatives, cigarette smoking among U.S. adults has been declining steadily (86)Sengupta R, et al. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2020: Turning science into lifesaving care. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26:5055. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In 2020, the most recent year for which such data are available, 12.5 percent of U.S. adults age 18 and older smoked cigarettes, a significant decline from 42.4 percent of adults in 1965, a year after the U.S. Surgeon General’s landmark report on smoking was published (87)Cornelius ME, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](88)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The health consequences of smoking-50 years of progress: A report of the Surgeon General. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Exposure to secondhand smoke, which increases the risk of lung cancer among nonsmokers, has dropped substantially over the past three decades (89)Tsai J, et al. Exposure to secondhand smoke among nonsmokers – United States, 1988-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1342-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Despite these positive trends, more than 47 million adults in the United States reported using a tobacco product in 2020 (87)Cornelius ME, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:397-405. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, an estimated 5.2 million high school students and 1.3 million middle school students in the U.S. used some type of tobacco product in 2021 (90)Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students – National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71:1-29. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These numbers are concerning because individuals who initiate smoking under the age of 17 have the highest risk of dying from cancer (84)Thomson B, et al. Association of smoking initiation and cessation across the life course and cancer mortality: Prospective study of 410000 US adults. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1901-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Evidence-based, local, state, and federal population-level interventions including tobacco price increases, public health campaigns, age and marketing restrictions, cessation counseling and FDA-approved medications, and smoke-free laws have the potential to further reduce smoking rates and smoking-related cancer burden in the United States (see Leveraging Policy to Reduce Tobacco-related Illness). In this regard, researchers and policy makers are working in concert to evaluate strategies, such as increasing the federal cigarette tax or including graphic warning labels on packs of cigarettes, that may increase smoking cessation and reduce new smoking initiation (91)Tam J, et al. Estimated prevalence of smoking and smoking-attributable mortality associated with graphic health warnings on cigarette packages in the US from 2022 to 2100. JAMA Health Forum 2021;2. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](92)Chaloupka FJ, et al. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob Control 2012;21:172-80. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

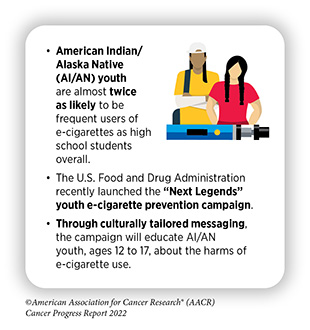

The use of other combustible tobacco products (e.g., cigars), smokeless tobacco products (e.g., chewing tobacco and snuff), and waterpipes (e.g., hookahs) is also associated with adverse health outcomes including cancer (93)Christensen CH, et al. Association of cigarette, cigar, and pipe use with mortality risk in the US population. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:469-76. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) were introduced to the U.S. market almost 15 years ago and have gained enormous popularity among U.S. middle and high school students and young adults ages 18 to 24 (see sidebar on E-Cigarettes: What Have We Learned and What Do We Need to Know?). The landscape of e-cigarette devices has evolved over the years to include different types of products such as prefilled pods (e.g., JUUL) or cartridge–based devices, and disposable (single use) devices (e.g., Puff Bar), among others. E-cigarettes come in flavors that appeal to youth, and these flavors are key drivers of use among youth and young adults (94)National Academy of Sciences. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. E-cigarettes can deliver nicotine, an extremely addictive substance which is harmful to the developing brain, at similar levels as traditional cigarettes (95)Prochaska JJ, et al. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control 2022;31:e88-e93. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](96)Goriounova NA, et al. Short- and long-term consequences of nicotine exposure during adolescence for prefrontal cortex neuronal network function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012;2:a012120. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While e-cigarettes emit fewer carcinogens than combustible tobacco, they still expose individuals to some toxic chemicals that can damage DNA and trigger inflammation (97)Goniewicz ML, et al. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e185937. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](98)Yu V, et al. Electronic cigarettes induce DNA strand breaks and cell death independently of nicotine in cell lines. Oral Oncol 2016;52:58-65. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](99)Muthumalage T, et al. E-cigarette flavored pods induce inflammation, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and DNA damage in lung epithelial cells and monocytes. Sci Rep 2019;9:19035. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](100)Tehrani MW, et al. Characterizing the chemical landscape in commercial e-cigarette liquids and aerosols by liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol 2021;34:2216-26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

After years of increase, the use of e-cigarettes declined among U.S. middle and high school students between 2019 and 2021 (21)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2021. Accessed: Dec 19, 2021.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (101)Park-Lee E, et al. Notes from the field: E-cigarette use among middle and high school students – National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1387-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These reductions may be attributed to an increased perception of harm from e-cigarettes as well as COVID-19-related factors such as having to stay at home, being afraid of parents finding out about e-cigarette use, and reduced access to e-cigarettes (111)Choi BM, et al. The decline in e-cigarette use among youth in the United States-an encouraging trend but an ongoing public health challenge. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2112464. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (112)New York Times. Youth vaping declined sharply for second year, new data show. Accessed: July 28, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, more than 2 million middle and high school students still reported using e-cigarettes in 2021 (90)Gentzke AS, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students – National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2021. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71:1-29. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Clearly, more work needs to be done to effectively curb the use of these products in young populations. FDA has implemented several restrictions on e-cigarettes in the past year (see Leveraging Policy to Reduce Tobacco-related Illness). It is imperative that all stakeholders continue to work together to determine the long-term health outcomes associated with e-cigarettes and identify new strategies to implement population-level regulations and reduce e-cigarette use among youth and young adults.

Maintain a Healthy Weight, Eat a Healthy Diet, and Stay Active

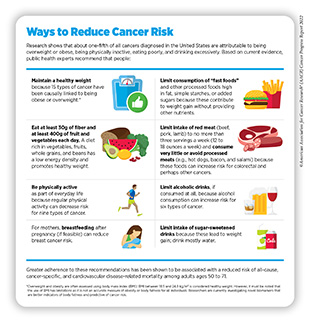

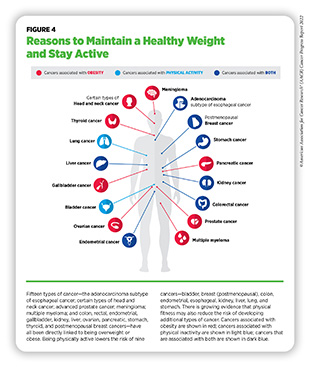

Nearly 20 percent of new cancer cases and 16 percent of cancer deaths in U.S. adults are attributable to a combination of excess body weight, poor diet, physical inactivity, and alcohol consumption (78)Islami F, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Being overweight or obese as an adult increases a person’s risk for 15 types of cancer; being physically active reduces risk for nine types of cancer (see Figure 4). Therefore, maintaining a healthy weight, being physically active, and consuming a balanced diet are effective ways a person can lower the risk of developing or dying from cancer (see sidebar on Ways to Reduce Cancer Risk). Identifying the underlying mechanisms by which obesity, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity increase cancer risk and quantifying the magnitude of such risks are areas of active research.

The prevalence of obesity has been rising steadily in the United States. In 2020, 16 states had an adult obesity prevalence at or above 35 percent, up from nine states in 2018 and 12 in 2019 (122)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity prevalence maps. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Additionally, 22 percent of children and young adults ages 2 to 19 were considered obese, in 2020 (123)State of Childhood Obesity. 2021 report: From crisis to opportunity. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These data, however, may not fully reflect the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has worsened obesity among most age groups (124)Restrepo BJ. Obesity prevalence among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Prev Med 2022;63:102-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](125)Lange SJ, et al. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons aged 2-19 years – United States, 2018-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1278-83. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are significant sociodemographic disparities in the prevalence of obesity, driven largely by structural inequities and societal injustices (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(127)Trust for America’s Health. The state of obesity 2021. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. As one example, in 2019-2020, 16 percent of U.S. youth ages 10 to 17 were obese (127)Trust for America’s Health. The state of obesity 2021. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].; the rates were higher among American Indian/Alaska Native youth (29 percent), non-Hispanic Black youth (24 percent), and Hispanic youth (21 percent) compared to non-Hispanic White youth (12 percent). It is important to address weight gain during early life since obesity during early childhood is associated with sustained overweight or obesity in adolescence and adulthood (128)Geserick M, et al. Acceleration of BMI in early childhood and risk of sustained obesity. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1303-12. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](129)Ward ZJ, et al. Simulation of growth trajectories of childhood obesity into adulthood. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2145-53. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is also evidence that obesity during adolescence can increase the risk of developing cancer later in life (130)Zohar L, et al. Adolescent overweight and obesity and the risk for pancreatic cancer among men and women: a nationwide study of 1.79 million Israeli adolescents. Cancer 2019;125:118-26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

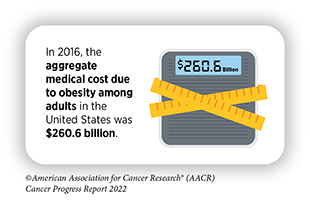

Beyond cancer, obesity increases the risk of developing several other health problems including high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, liver disease, kidney disease and type 2 diabetes which by itself is a risk factor for cancer (see Reduce Risk of Diabetes).

Emerging data indicate that weight loss intervention through bariatric surgery may lower the future risk of certain obesity-related cancers (132)Tao W, et al. Cancer risk after bariatric surgery in a cohort study from the five nordic countries. Obes Surg 2020;30:3761-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](133)Schauer DP, et al. Bariatric surgery and the risk of cancer in a large multisite cohort. Ann Surg 2019;269:95-101. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to a recent study, among adults with obesity, bariatric surgery compared to no surgery was associated with a 32 percent reduction in obesity-associated cancer incidence and 48 percent reduction in cancer-related mortality (134)Aminian A, et al. Association of bariatric surgery with cancer risk and mortality in adults with obesity. JAMA 2022;327:2423-33. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While further research is needed to elucidate whether weight loss can effectively mitigate risks of developing and/or dying from all obesity-related cancers, identifying equitable strategies including lifestyle and therapeutic interventions to address obesity must certainly be a top priority among U.S. public health efforts.

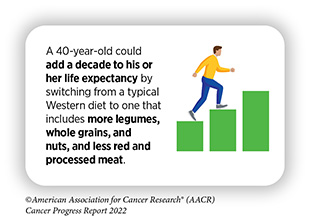

Complex and interrelated issues ranging from health literacy and other socioeconomic factors, to environmental, biological, and individual lifestyle factors may contribute to obesity; there is, however, sufficient evidence that consumption of high-calorie, energy-dense foods and beverages and lack of physical activity play a significant role in obesity (127)Trust for America’s Health. The state of obesity 2021. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. To achieve and maintain good health, U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services, in Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, recommend that individuals follow a healthy dietary pattern at every stage of life (136)Phillips JA. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Workplace Health Saf 2021;69:395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to the guidelines, all individuals should fulfill their nutritional needs by consuming nutrient-dense food and beverages including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, lean meat, eggs, seafood, beans, legumes, nuts, and vegetable oil, and limit foods and beverages that are high in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, as well as alcoholic beverages (136)Phillips JA. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Workplace Health Saf 2021;69:395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

In the United States, more than five percent of all newly diagnosed cancer cases among adults are attributable to eating a poor diet (137)Zhang FF, et al. Preventable cancer burden associated with poor diet in the united states. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2019;3:pkz034. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Based on recent data, in 2019, only 12 percent and 10 percent of U.S. adults met their fruit and vegetable intake recommendations, respectively (138)Lee SH, et al. Adults meeting fruit and vegetable intake recommendations – United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:1-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. High intake of highly processed foods contributes to obesity. Therefore, it is concerning that among U.S. children and youth ages 2 to 19 years, the estimated percentage of total energy consumed from highly processed foods increased from 61 percent to 67 percent between 1999 and 2018 (139)Wang L, et al. Trends in consumption of ultraprocessed foods among US youths aged 2-19 years, 1999-2018. JAMA 2021;326:519-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are significant disparities in diet quality among different segments of the U.S. population attributable largely to socioeconomic and geographic factors. Based on a recent report, individuals who are Black, have low education, or live in rural areas and food deserts—neighborhoods that lack access to healthy food retail such as supermarkets, and have an overabundance of unhealthy and fast-food options—are more likely to have poor diet quality (140)McCullough ML, et al. Association of socioeconomic and geographic factors with diet quality in US adults. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2216406. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In contrast, higher access to grocery stores, lower access to fast food, higher income and college education are associated with eating healthily and maintaining a healthy weight (141)Althoff T, et al. Large-scale diet tracking data reveal disparate associations between food environment and diet. Nat Commun 2022;13:267. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These findings underscore the necessity for public policies to increase access to affordable nutritious food, as well as the need for educational interventions to improve nutritional knowledge for everyone, specifically among medically underserved populations.

A major barrier to healthy diet is food insecurity, defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as the lack of access by all people in a household at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. Many studies have found an association between food insecurity and excess body weight (127)Trust for America’s Health. The state of obesity 2021. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Researchers have hypothesized several mechanisms by which food insecurity may lead to obesity, including increased consumption of unhealthy diet, stress and anxiety generating higher levels of stress hormones, which heighten appetite, and a physiological response to reduced food availability leading to higher fat storage in the body (127)Trust for America’s Health. The state of obesity 2021. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

One initiative that has been effective in increasing the consumption of healthy food and lowering the rates of obesity among children from low-income families is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (143)Daepp MIG, et al. WIC food package changes: Trends in childhood obesity prevalence. Pediatrics 2019;143. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](144)Pan L, et al. State-specific prevalence of obesity among children aged 2-4 years enrolled in the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children – United States, 2010-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1057-61. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, a program (SuperSNAP) that provides additional funds to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program beneficiaries for purchase of fruits and vegetables was recently shown to be associated with significant increases in healthy food purchasing (145)Berkowitz SA, et al. Association of a fruit and vegetable subsidy program with food purchases by individuals with low income in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2120377. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While ongoing research needs to evaluate the long-term health outcomes of this program, incentives like SuperSNAP are vital, especially for populations that experience food insecurity.

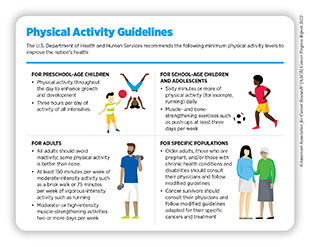

Research indicates that over 46,000 U.S. cancer cases annually could potentially be avoided if everyone met the recommended physical activity guidelines (see sidebar on Physical Activity Guidelines) (146)Minihan AK, et al. Proportion of cancer cases attributable to physical inactivity by US State, 2013-2016. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2022;54:417-23. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Engaging in recommended levels of physical activity can lower the risks for developing nine types of cancer (see Figure 4), and emerging evidence indicates that there may be risk reduction for even more cancer types (115)Matthews CE, et al. Amount and intensity of leisure-time physical activity and lower cancer risk. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:686-97. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](116)Patel AV, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable Report on physical activity, sedentary behavior, and cancer prevention and control. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019;51:2391-402. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](117)Moore SC, et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity With Risk of 26 Types of Cancer in 1.44 Million Adults. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:816-25. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition to cancer, muscle-strengthening and aerobic activities can also lower the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes (147)Momma H, et al. Muscle-strengthening activities are associated with lower risk and mortality in major non-communicable diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:755-63. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to a recent study in U.S. adults, an additional 20 minutes of exercise a day could prevent nearly 210,000 deaths each year (148)Saint-Maurice PF, et al. Estimated number of deaths prevented through increased physical activity among US adults. JAMA Intern Med 2022;182:349-52. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, according to a current report, only 35 percent of men and 27 percent of women age 18 and older in the U.S. met the federal guideline for muscle-strengthening physical activity in 2020 (149)Heitz E. Quickstats: Percentage of adults aged ≥18 years who met the federal guidelines for muscle-strengthening physical activity, by age group and sex – National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:642. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are also striking sociodemographic disparities among those who are physically active, with a higher prevalence of activity recorded among adults who are White, have a college education, have higher income, and have private health insurance (151)Islami F, et al. American Cancer Society’s report on the status of cancer disparities in the United States, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:112-43. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Living in low-income neighborhoods, which are more likely to lack safe and affordable options for physical exercise, such as gyms, biking and hiking trails, and biking and walking paths, contributes to such disparities. It is imperative that health care professionals and policy makers work together to increase awareness of the benefits of physical activity and support programs and policies that facilitate an active lifestyle for everyone along their lifespan.

Limit Alcohol Consumption

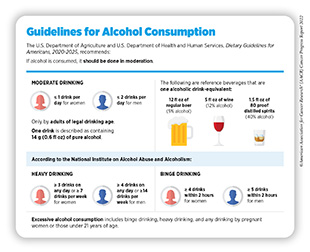

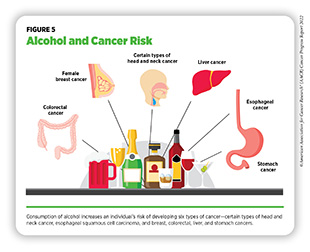

Alcohol consumption increases the risk for six different types of cancer (152)World Cancer Research Fund. Diet, activity and cancer. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Figure 5), and emerging evidence indicates that there may be increased risks for additional cancer types (153)Papadimitriou N, et al. An umbrella review of the evidence associating diet and cancer risk at 11 anatomical sites. Nat Commun 2021;12:4579. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Even modest intake of alcohol may increase cancer risk, but the greatest risks are associated with excessive and/or long-term consumption (154)LoConte NK, et al. Alcohol and cancer: A statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:83-93. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](155)White AJ, et al. Lifetime alcohol intake, binge drinking behaviors, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186:541-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](156)Xi B, et al. Relationship of alcohol consumption to all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer-related mortality in U.S. Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:913-22. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (see sidebar on Guidelines for Alcohol Consumption). Research indicates that excessive drinking during early adulthood might increase cancer risk later in life even if drinking stops or decreases in middle age (157)Bassett JK, et al. Alcohol intake trajectories during the life course and risk of alcohol-related cancer: A prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer 2022;151:56-66. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, according to a recent global analysis, among individuals consuming harmful amounts of alcohol in 2020, nearly 60 percent were ages 15 to 39 years (158)GBD Alcohol Collaborators. Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020. Lancet 2022;400:185-235. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

In the United States, alcohol consumption accounted for greater than 75,000 cancer cases and nearly 19,000 cancer deaths annually between 2013 and 2016 (159)Goding Sauer A, et al. Proportion of cancer cases and deaths attributable to alcohol consumption by US state, 2013-2016. Cancer Epidemiol 2021;71:101893. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Consumption of alcohol varies by sociodemographics and is higher among men with lower education and lower income compared to men who are college graduates and have higher income, as well as among certain sexual and gender minority populations (160)Bandi P, et al. Updated review of major cancer risk factors and screening test use in the United States in 2018 and 2019, with a focus on smoking cessation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2021;30:1287-99. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic has further increased alcohol use (161,162). These data underscore the importance of adhering to comprehensive guidelines to limit and/or eliminate alcohol intake and minimize the risk of developing a disease or dying due to alcohol.

Future efforts focused on evidence-based policy interventions, such as regulating alcohol retail density, taxes, and prices, as well as public education (e.g., cancer-specific warning labels displayed on alcoholic beverages), need to be implemented along with effective clinical strategies to reduce the burden of alcohol-related cancers. In this regard, a recent survey indicated that nearly 65 percent of U.S. citizens support adding warning labels and drinking guidelines to alcohol containers (164)Seidenberg AB, et al. Awareness of alcohol as a carcinogen and support for alcohol control policies. Am J Prev Med 2022;62:174-82. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, awareness among survey respondents of the risks of cancer from alcohol consumption was associated with a greater support of warning labels indicating that increasing public awareness of the alcohol–cancer link may increase support for alcohol control policies. Increasing public awareness of the harmful effects of alcohol is important in light of data from a recent survey that indicate only 31 percent of Americans recognize alcohol is a risk factor for cancer (165)American Society of Clinical Oncology. ASCO 2019 cancer opinion survey. Accessed: July 28, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

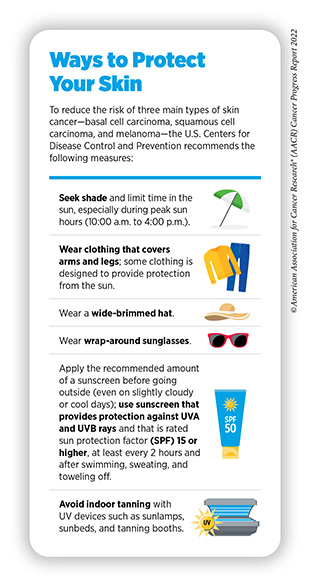

Protect Skin from UV Exposure

Exposure to UV radiation from the sun or indoor tanning devices poses a serious threat for the development of the three main types of skin cancer—basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma, the latter being the deadliest form of skin cancer. Overall, exposure to UV light accounts for four to six percent of all cancers and is responsible for 95 percent of skin melanomas (78)Islami F, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Thus, one of the most effective ways a person can reduce the risk of skin cancer is by practicing sun-safe habits and not using UV indoor tanning devices (see sidebar on Ways to Protect Your Skin).

In the United States, melanoma incidence has been rising for decades. Based on a new analysis, during 2009 to 2018, incidence of malignant melanoma of the skin increased by an average of 1.2 percent per year (166)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incidence of malignant melanoma of the skin–United States, 2009–2018 Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Public education regarding skin cancer risk reduction is extremely important considering findings from many recent surveys conducted in the U.S. indicate a lack of understanding of skin cancer and sun protection and high incidence of sunburns among participants (2021) (167)Strome A, et al. Assessment of sun protection knowledge and behaviors of US youth. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2134550. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In addition, there are disparities in the level of knowledge about the dangers of sun exposure and importance of using sunscreen, with Black and Hispanic individuals reporting less knowledge and being less likely to use sunscreen compared to White individuals (168)Cheng CE, et al. Health disparities among different ethnic and racial middle and high school students in sun exposure beliefs and knowledge. J Adolesc Health 2010;47:106-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](169)Summers P, et al. Sunscreen use: Non-Hispanic Blacks compared with other racial and/or ethnic groups. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:863-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Use of indoor UV tanning devices increases a person’s risk for melanoma. One population with a high prevalence of indoor tanning is sexual minority men compared to heterosexual men (170)Mansh M, et al. Indoor tanning and melanoma: are gay and bisexual men more at risk? Melanoma Manag 2016;3:89-92. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](171)Mansh M, et al. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:1308-16. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Sexual minority men are also more likely than heterosexual men to report having skin cancer (171)Mansh M, et al. Association of skin cancer and indoor tanning in sexual minority men and women. JAMA Dermatol 2015;151:1308-16. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Laws prohibiting tanning can be effective in reducing tanning practices and may reduce the incidence of future melanoma cases and associated health care costs (172)Stapleton JL, et al. Prevalence and location of indoor tanning among high school students in new jersey 5 years after the enactment of youth access restrictions. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:1223-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](173)Eskander A, et al. To ban or not to ban tanning bed use for minors: A cost-effectiveness analysis from multiple US perspectives for invasive melanoma. Cancer 2021;127:2333-41. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](174)Eden M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a policy-based intervention to reduce melanoma and other skin cancers associated with indoor tanning. Br J Dermatol 2022;187:105-14. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, as of January 1, 2021, in the U.S., only 20 states and the District of Columbia have laws prohibiting tanning for minors (under the age of 18) (175)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts and Figures 2021-2022. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. It is vital that all stakeholders in public health continue to work together to develop and implement more effective policy changes and public education campaigns to reduce the practice of indoor tanning, especially among high-risk populations.

Prevent and Eliminate Infection with Cancer-causing Pathogens

Persistent infection with several pathogens—disease-causing bacteria, viruses, and parasites—increases a person’s risk for several types of cancer (see Table 3). In the United States, about three percent of all cancer cases are attributable to infection with pathogens (78)Islami F, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31-54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Globally, an estimated 13 percent of all cancer cases in 2018 were attributable to pathogenic infections, with more than 90 percent of these cases attributable to four pathogens: human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and Helicobacter pylori (177)de Martel C, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e180-e90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](178)Hong CY, et al. Incidence of extrahepatic cancers among individuals with chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection: A nationwide cohort study. J Viral Hepat 2020;27:896-903. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Individuals can significantly lower their risks by protecting themselves from infection or by seeking treatment, if available, to eliminate an infection (see sidebar on Ways to Reduce Cancer Risk from Pathogens). It is important to note that even though strategies to eliminate, treat, or prevent infection with Helicobacter pylori, HBV, HCV, and HPV can significantly lower an individual’s risks for developing cancers, these strategies are not effective at treating infection-related cancers once they develop.

Chronic infection with HBV and HCV can cause liver cancer and is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for additional malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma (179)Lemaitre M, et al. Hepatitis b virus associated b-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma in non-endemic areas. Blood 2018;132:4228-. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](180)Couronne L, et al. From hepatitis C virus infection to B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2018;29:92-100. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, after decades of decline, the number of new HBV infections is now rising among adults age 40 and older, despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine (181)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rates of reported acute Hepatitis B virus infection, by age group — United States, 2004–2019. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

As a result, CDC recently recommended that all adults ages 19 to 59 years receive a vaccination for HBV (182)Weng MK, et al. Universal Hepatitis B vaccination in adults aged 19-59 years: Updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices – United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:477-83. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Current evidence shows significant gaps in the perception and treatment of HBV, especially among racial and ethnic minorities, highlighting the need for community-based, culturally appropriate interventions to mitigate the disparate burden of the virus (183)Ye Q, et al. Substantial gaps in evaluation and treatment of patients with hepatitis B in the US. J Hepatol 2022;76:63-74. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](184)Jones P, et al. A mixed-methods approach to understanding perceptions of hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma among ethnically diverse Black communities in South Florida. Cancer Causes Control 2020;31:1079-91. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Acute infection with HCV is often asymptomatic but more than half of these cases progress to chronic infection. The rate of reported acute HCV cases in the United States increased by 89 percent between 2014 and 2019, with the highest rate among AI/AN persons (185)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report 2019. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

To eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently released the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021–2025) (187)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Viral Hepatitis national strategic plan for the United States: A Roadmap to elimination (2021–2025). Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The primary goals listed in the report are to prevent new infections, improve hepatitis-related health outcomes for infected individuals, reduce disparities and health inequities related to hepatitis, improve surveillance of viral hepatitis, and bring together all relevant stakeholders in coordinating efforts to address the hepatitis epidemic.

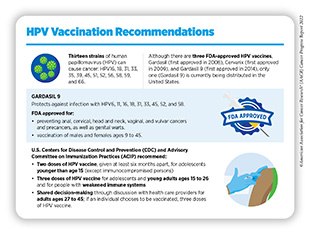

Persistent infection with HPV is responsible for almost all cervical cancers, 90 percent of anal cancers, about 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancers, and more than half of all vaginal, vulvar, and penile cancers (188)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basic information about HPV and cancer. Accessed: July 28, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This knowledge has driven the development of vaccines that prevent infection with some cancer-causing strains of HPV and the development of a clinical test that detects cancer-causing HPV strains in cervical cells. There are 13 different types of HPV that can cause cancers; the HPV vaccine currently used in the United States, Gardasil 9, can protect against nine of these HPV strains (see sidebar on HPV Vaccination Recommendations) (188)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basic information about HPV and cancer. Accessed: July 28, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

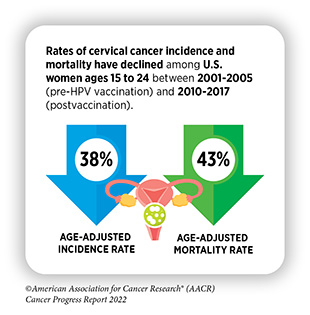

There is emerging evidence affirming that the receipt of guideline-concordant HPV vaccination significantly lowers the risk of infection with HPV types that are covered by the vaccines and dramatically reduces the incidence of and mortality from cervical cancers among the vaccinated (189)Rosenblum HG, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine impact and effectiveness through 12 years after vaccine introduction in the United States, 2003 to 2018. Ann Intern Med 2022;175:918-26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](190)Liao CI, et al. Trends in Human papillomavirus-associated cancers, demographic characteristics, and vaccinations in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e222530. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](191)Falcaro M, et al. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet 2021;398:2084-92. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](192)Tabibi T, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination and trends in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the US. JAMA Pediatr 2022;176:313-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to a recent analysis, prior to the HPV vaccination approval, cervical cancer rates among 20- to 24-year-old U.S. women were decreasing at 2.3 percent annually during 2001 and 2011; after the vaccine approval, these rates decreased at 9.5 percent per year during 2011 and 2017 (190)Liao CI, et al. Trends in Human papillomavirus-associated cancers, demographic characteristics, and vaccinations in the US, 2001-2017. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e222530. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, recent findings suggest that the incidence of certain anal cancers has decreased among vaccine-eligible individuals ages 20 to 44 between 2009 and 2018 (193)Berenson AB, et al. Association of human papillomavirus vaccination with the incidence of squamous cell carcinomas of the anus in the US. JAMA Oncol 2022;8:1-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Despite the positive impacts, the uptake of HPV vaccines has been suboptimal in the United States. While there has been some progress in recent years, only 56 percent of boys and 61 percent of girls who are eligible were up to date on their vaccination regimen in 2020 (194)Pingali C, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1183-90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These numbers stand in sharp contrast to those from the United Kingdom where high uptake of HPV vaccination among 12 to 13-year-old girls, since the onset of the program in 2008, has nearly eliminated cervical cancer in women born since September 1995 (191)Falcaro M, et al. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet 2021;398:2084-92. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Until recently, cervical cancer was the most common HPV-related cancer in the United States. However, the incidence of HPV-related oropharyngeal and anal cancers has been increasing and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma was recently reported to have become the most common HPV-associated cancer in the United States. Therefore, developing effective strategies to improve the uptake of HPV vaccines could have immense public health benefits.

All stakeholders must work together and develop better strategies to increase the uptake of HPV vaccination in the United States. These include ensuring that health care providers recommend HPV vaccination to all eligible adolescents and their parents, improving provider-parent communication, increasing parental awareness, and removing structural and financial barriers to increase access to vaccination. In this regard, there is new evidence that a single dose of the HPV vaccine may protect against cancer-causing infections (196)Basu P, et al. Vaccine efficacy against persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) 16/18 infection at 10 years after one, two, and three doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine in girls in India: a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:1518-29. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](197)Barnabas RV, et al. Efficacy of single-dose HPV vaccination among young African women. NEJM Evid 2022;1:EVIDoa2100056. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Giving just one HPV vaccine dose instead of multiple doses, as is currently recommended, can potentially reduce the cost and simplify the logistics of vaccination, increasing the overall uptake, particularly in low-resource settings. Additionally, there is a vital need for increased public education to enhance trust in vaccination considering recent evidence that hesitancy related to the HPV vaccine has increased among parents (198)Sonawane K, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine safety concerns and adverse event reporting in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2124502. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Reduce Risk of Diabetes

Diabetes is a chronic health condition that affects how food is converted into energy. There are three main types, type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes. In healthy individuals, food is broken down into sugar, also called glucose, which is released into the bloodstream and taken up by cells for use as energy through the help of the molecule insulin. Individuals with diabetes do not make enough insulin or cannot efficiently use the insulin the body makes. Lack of enough insulin leads to excessive blood sugar levels that can cause serious health problems, such as heart disease, vision loss, and kidney disease. Researchers have found that individuals with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes are at an increased risk of developing certain types of cancer such as liver, pancreatic, endometrial, colorectal, breast, and bladder cancer (199)Giovannucci E, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:207-21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Ongoing studies are evaluating the risks for other cancer types (200)Zhu B, et al. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and cancers and its underlying mechanisms. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:800995. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](201)Shahid RK, et al. Diabetes and cancer: Risk, challenges, management and outcomes. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, there is evidence that diabetes may be associated with increased mortality from cancer (200)Zhu B, et al. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and cancers and its underlying mechanisms. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:800995. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

In the U.S. 37.3 million people have diabetes. Unfortunately, one of five individuals is unaware of having the condition (202)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A snapshot: Diabetes in the United States. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. There are also disparities in the burden of diabetes. In the U.S., prevalence is higher among Black and Hispanic populations compared to the White population (203)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Age-adjusted prevalence of diagnosed, undiagnosed, and total diabetes among adults aged 18 years or older, United States, 2017–2020. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Diabetes (type 2) and cancer share several nonmodifiable and modifiable risk factors such as aging, obesity, poor diet, physical inactivity, and smoking. While the increased risk for cancer may be explained, in part, by the shared risk factors, researchers have uncovered potential mechanisms that may explain a direct link between diabetes and cancer. These include diabetes-associated inflammation and high levels of insulin and glucose, all of which have been independently linked with cancer development (204)Rey-Renones C, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cancer: Epidemiology, physiopathology and prevention. Biomedicines 2021;9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Identifying the exact mechanisms by which diabetes increases cancer risk and targeting those pathways to reduce risks are areas of extensive research.

Fortunately, there are many ways in which individuals with diabetes can lower their cancer risk. Keeping blood sugar levels under control and avoiding hyperglycemia are key to risk reduction. People with diabetes can lower their risk of cancer by adopting a healthy lifestyle. Eating a healthful diet rich with vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, engaging in regular physical activity, limiting alcohol consumption, and eliminating tobacco use may significantly reduce the risk of diabetes and cancer. It is important that patients with diabetes be aware of their increased cancer risk and undergo recommended age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings (205)American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 2019;42:S34-S45. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Be Cognizant of Reproductive and Hormonal Influences

Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Historically, parous women—women who have given birth—were known to be less likely to develop breast cancer than nulliparous women—women who have not given birth—due to the protective effect of pregnancy. However, in the last

five decades, there has been a substantial increase in age at first pregnancy and reduction in the number of children women have, leading to the uncovering of differential effects of pregnancy on breast cancer. Importantly, recent studies have shown that giving birth reduces the risk in mothers for developing a common type of breast cancer, known as estrogen receptor-positive tumor (206)Nichols HB, et al. Breast cancer risk after recent childbirth: A pooled analysis of 15 prospective studies. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:22-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](207)Ambrosone CB, et al. Relationships between breast feeding and breast cancer subtypes: Lessons learned from studies in humans and in mice. Cancer Res 2020;80:4871-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](208)Jung AY, et al. Distinct reproductive risk profiles for intrinsic-like breast cancer subtypes: pooled analysis of population-based studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, the risk reduction in breast cancer incidence is manifested only after a decade or longer following a woman’s last pregnancy, with greater protection conferred with increasing time (206)Nichols HB, et al. Breast cancer risk after recent childbirth: A pooled analysis of 15 prospective studies. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:22-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](207)Ambrosone CB, et al. Relationships between breast feeding and breast cancer subtypes: Lessons learned from studies in humans and in mice. Cancer Res 2020;80:4871-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](208)Jung AY, et al. Distinct reproductive risk profiles for intrinsic-like breast cancer subtypes: pooled analysis of population-based studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The net result is that parous women are at reduced risk for developing breast cancer after menopause (when most breast cancers are diagnosed) compared to their nulliparous peers. Further research is needed to understand this protective mechanism.

In contrast, during the five to ten years after giving birth, referred to as the postpartum period, women face an elevated risk for breast cancer diagnosis compared to those who have never given birth (206)Nichols HB, et al. Breast cancer risk after recent childbirth: A pooled analysis of 15 prospective studies. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:22-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](207)Ambrosone CB, et al. Relationships between breast feeding and breast cancer subtypes: Lessons learned from studies in humans and in mice. Cancer Res 2020;80:4871-7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](208)Jung AY, et al. Distinct reproductive risk profiles for intrinsic-like breast cancer subtypes: pooled analysis of population-based studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Because these cancers occur in young, mostly premenopausal women, they are referred to as early-onset breast cancers. Further, recent childbirth associates with increased risk for estrogen receptor-negative tumors, an intractable form of breast cancer (209)Vohra SN, et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of postpartum-associated breast cancer in the carolina breast cancer study phase I-III, 1993-2013. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2022;31:561-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Overall, young women are at a higher risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer and this risk increases soon after childbirth, but then attenuates with time (206)Nichols HB, et al. Breast cancer risk after recent childbirth: A pooled analysis of 15 prospective studies. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:22-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](208)Jung AY, et al. Distinct reproductive risk profiles for intrinsic-like breast cancer subtypes: pooled analysis of population-based studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](209)Vohra SN, et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of postpartum-associated breast cancer in the carolina breast cancer study phase I-III, 1993-2013. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2022;31:561-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Thus, for young women, a recent childbirth increases the risk of early onset breast cancer, particularly poor prognostic estrogen receptor negative cancers.

Recent data indicate that breast cancers arising in young women during postpartum period, referred to as postpartum breast cancers, are associated with an increased risk for metastasis and worse outcomes compared to breast cancers diagnosed in young, premenopausal women who have not given birth (210)Hartman EK, et al. The prognosis of women diagnosed with breast cancer before, during and after pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;160:347-60. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](211)Shao C, et al. Prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2020;20:746. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](212)Lefrere H, et al. Postpartum breast cancer: mechanisms underlying its worse prognosis, treatment implications, and fertility preservation. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2021;31:412-22. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](213)Shagisultanova E, et al. Overall survival is the lowest among young women with postpartum breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2022;168:119-27. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Even early-stage, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers, which otherwise have favorable prognosis, have poor outcomes when diagnosed as postpartum breast cancer, and poor prognostic gene expression signature (214)Goddard ET, et al. Association between postpartum breast cancer diagnosis and metastasis and the clinical features underlying risk. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e186997. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](215)Jindal S, et al. Postpartum breast cancer has a distinct molecular profile that predicts poor outcomes. Nat Commun 2021;12:6341. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Research has also shown that breast cancers occurring during pregnancy have different biological characteristics and better prognosis compared to those that are diagnosed during the postpartum period (216)Amant F, et al. The definition of pregnancy-associated breast cancer is outdated and should no longer be used. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:753-4. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](217)Amant F, et al. Outcome of breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy during pregnancy compared with non-pregnant controls. Eur J Cancer 2022;170:54-63. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Identifying interventions that may alleviate the tumor-promoting potential of recent childbirth, as well as best therapeutic options to treat postpartum breast cancers are areas of extensive investigation (218)Schedin P, et al. Can breast cancer prevention strategies be tailored to biologic subtype and unique reproductive windows? J Natl Cancer Inst 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There is evidence that breastfeeding can be protective against breast cancer development in mothers (219)Millikan RC, et al. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:123-39. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](220)Lord SJ, et al. Breast cancer risk and hormone receptor status in older women by parity, age of first birth, and breastfeeding: a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:1723-30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](221)Fortner RT, et al. Parity, breastfeeding, and breast cancer risk by hormone receptor status and molecular phenotype: results from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Breast Cancer Res 2019;21:40. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Emerging data suggest that breastfeeding may also be associated with a lower risk of ovarian cancer development (222)Moorman PG, et al. Reproductive factors and ovarian cancer risk in African-American women. Ann Epidemiol 2016;26:654-62. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](223)Babic A, et al. Association between breastfeeding and ovarian cancer risk. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:e200421. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These protective effects have been described in both Black and White women (208)Jung AY, et al. Distinct reproductive risk profiles for intrinsic-like breast cancer subtypes: pooled analysis of population-based studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](219)Millikan RC, et al. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:123-39. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](224)Anstey EH, et al. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk reduction: Implications for black mothers. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:S40-S6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](225)Palmer JR, et al. Parity, lactation, and breast cancer subtypes in African American women: results from the AMBER Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Based on current evidence, breastfeeding reduces the increased risk of estrogen receptor-negative cancers that is associated with having children. Notably, the increased risk of triple-negative breast cancer diagnosis associated with giving birth can be reduced by breastfeeding, with longer durations of breastfeeding further decreasing the risk (118)World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project. Expert Report 2018. Lactation and the risk of cancer. Accessed:[cited 2020 Jul 15].(208)Jung AY, et al. Distinct reproductive risk profiles for intrinsic-like breast cancer subtypes: pooled analysis of population-based studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](219)Millikan RC, et al. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:123-39. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](224)Anstey EH, et al. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk reduction: Implications for black mothers. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:S40-S6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](225)Palmer JR, et al. Parity, lactation, and breast cancer subtypes in African American women: results from the AMBER Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](226)John EM, et al. Reproductive history, breast-feeding and risk of triple negative breast cancer: The Breast Cancer Etiology in Minorities (BEM) study. Int J Cancer 2018;142:2273-85. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Studies have shown that breastfeeding decreases the risk of triple-negative breast cancers for younger Black women (219)Millikan RC, et al. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:123-39. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](224)Anstey EH, et al. Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk reduction: Implications for black mothers. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:S40-S6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](227)Ma H, et al. Reproductive factors and the risk of triple-negative breast cancer in white women and African-American women: a pooled analysis. Breast Cancer Res 2017;19:6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, the awareness of the benefits of breastfeeding in reducing cancer risk is low among U.S. women (228)Hoyt-Austin A, et al. Awareness that breastfeeding reduces breast cancer risk: 2015-2017 National Survey of Family Growth. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:1154-6. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Culturally tailored public education and public health policies in support of lactation are needed, specifically for medically underserved populations, such as young Black women, who have a disproportionately higher incidence of triple-negative breast cancer, and a lower prevalence of breastfeeding compared to all other U.S. racial and ethnic groups (229)Chiang KV, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding initiation horizontal line United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:769-74. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](230)Beauregard JL, et al. Racial disparities in breastfeeding initiation and duration among U.S. infants born in 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:745-8. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) refers to treatments that aim to relieve the common symptoms of menopause and the long-term biological changes, such as bone loss, that take place after menopause. These changes occur due to the decline in the levels of the hormones estrogen and progesterone, in a woman’s body. HRT usually involves treatment with estrogen alone or estrogen in combination with progestin, a synthetic hormone similar to progesterone. Women who have a uterus are prescribed the estrogen and progestin combination. This is because estrogen alone, but not in combination with progestin, is associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer, a type of cancer that forms in the tissue lining the uterus. Estrogen alone is used only in women who have had their uteruses removed.

Comprehensive evidence about the health effects of HRT was obtained from clinical trials conducted by NIH as part of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). The data indicated that women who use the estrogen and progestin combination have an increased risk of developing breast cancer (231)Chlebowski RT, et al. Association of menopausal hormone therapy with breast cancer incidence and mortality during long-term follow-up of the women’s health initiative randomized clinical trials. JAMA 2020;324:369-80. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](232)Chlebowski RT, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and breast cancer detection by means of mammography and breast biopsy. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:370-7; quiz 45. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The risk is greater with longer duration of use and is nearly two fold higher among women who have used estrogen plus progestin combination for 10 years or longer compared to those who never used HRT (233)Chlebowski RT, et al. Breast cancer after use of estrogen plus progestin in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2009;360:573-87. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](234)Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet 2019;394:1159-68. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](235)Wang SM, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor-defined breast cancer: results from a 15-year prospective analysis of NIH-AARP cohort. Breast Cancer Res 2020;22:129. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Women who are no longer using HRT have a lower risk than current users but remain at an elevated risk for more than a decade after they have stopped taking the drugs (234)Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet 2019;394:1159-68. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. More recently, analyses from the United Kingdom have corroborated the data from WHI and showed that long-term use of the estrogen and progestin combination is associated with an increase in the risk of breast cancer (236)Vinogradova Y, et al. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ 2020;371:m3873. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](237)Chlebowski RT, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer. Cancer J 2022;28:169-75. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Individuals who are seeking relief from menopausal symptoms should discuss with their health care providers the advantages and possible risks of using HRT before deciding what is right for them.

Another area of ongoing investigation in exogenous hormone use is the differential cancer risks among individuals undergoing gender-affirming hormonal therapy (238)Jackson SS, et al. Understanding the role of sex hormones in cancer for the transgender community. Trends Cancer 2022;8:273-5. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While current data is very limited, there is emerging evidence indicating an increased risk of breast cancer but a lower risk of prostate cancer among trans women who received gender-affirming hormonal therapy compared to age-matched cisgender men and a lower risk of breast cancer in trans men who received gender-affirming hormonal therapy compared to age-matched cisgender women (238)Jackson SS, et al. Understanding the role of sex hormones in cancer for the transgender community. Trends Cancer 2022;8:273-5. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](239)de Blok CJM, et al. Breast cancer risk in transgender people receiving hormone treatment: nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. BMJ 2019;365:l1652. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](240)de Nie I, et al. Prostate cancer incidence under androgen deprivation: Nationwide cohort study in trans women receiving hormone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:e3293-9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Long-term, longitudinal, population-based studies are needed to comprehensively assess the risk of cancers in these understudied and medically underserved populations.

Limit Exposure to Environmental Risk Factors

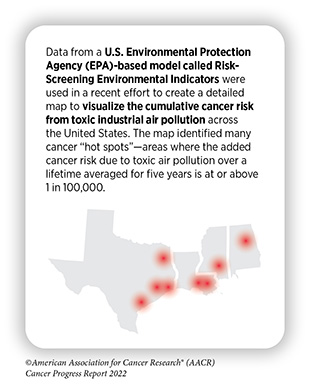

Environmental exposures to pollutants and certain occupational agents can increase a person’s risk of cancer. For example, radon, a naturally occurring radioactive gas that comes from the breakdown of uranium in soil, rock, and water, is the leading cause of U.S. lung cancer deaths among never smokers albeit levels of naturally occurring radon vary widely based on geographic location within the country (175)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts and Figures 2021-2022. Accessed: July 6, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(241)National Cancer Institute. Cancer Trends Progress Report. Accessed: July 28, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Other examples of environmental carcinogens include arsenic, asbestos, lead, radiation, and benzene (242)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Toxicology Program: 15th Report on Carcinogens. Accessed: July 13, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), environmental risk factors account for nearly 20 percent of all cancers globally, most of which occur in low- and middle-income countries.

It can be difficult for people to avoid or reduce their exposure to environmental carcinogens, and like behavioral and inherited factors not every exposure will lead to cancer. The intensity and duration of exposure, combined with an individual’s biological characteristics such as genetic makeup, and lifestyle factors determine each person’s chances of developing cancer over his or her lifetime. In addition, when studying environmental cancer risk factors, it is important to consider that exposure to several environmental cancer risk factors may occur simultaneously. Growing knowledge of the environmental pollutants to which different segments of the U.S. population are exposed highlights new opportunities for education and policy initiatives to improve public health (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Outdoor air pollution is classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an affiliate of WHO, as a potential cause of cancer in humans (244)Loomis D, et al. The carcinogenicity of outdoor air pollution. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1262-3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Two types of air pollution are most common in the United States: ozone and particle pollution. Particle pollution refers to a mix of tiny solid and liquid particles that are in the air we breathe, and in 2013, IARC concluded that particle pollution may cause lung cancer. Nearly 21 million people in the United States were exposed year-round to unhealthy levels of particle pollution between 2018 and 2020 (83)American Lung Association. State of the Air 2022. Accessed: July 13, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Racial and ethnic minorities and people living in poverty were at an increased risk of being exposed to polluted air (83)American Lung Association. State of the Air 2022. Accessed: July 13, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. New laws, regulations, and policies to reduce the release of pollutants into the atmosphere are urgently needed to reduce the adverse health effects of air pollution, including cancer.

Regulatory policies are also needed to combat the adverse health impact of wildfires considering the recent increase in these hazardous events in the Pacific Northwest. Wildfires emit many carcinogenic pollutants into the air, water, terrestrial, and indoor environments (245)Korsiak J, et al. Long-term exposure to wildfires and cancer incidence in Canada: a population-based observational cohort study. Lancet Planet Health 2022;6:e400-e9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is emerging evidence that indicates long-term exposure to wildfires may increase the risk of certain cancers (245)Korsiak J, et al. Long-term exposure to wildfires and cancer incidence in Canada: a population-based observational cohort study. Lancet Planet Health 2022;6:e400-e9. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (246)Oregon Public Broadcasting. Analysis suggests Oregon’s wildfire smoke comes with a side of cancer-causing chemicals. Accessed: July 28, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Certain chemical compounds that are used in agriculture, in the home, in some occupations such as pest control or weed control, and to protect us from fires, such as fire retardants, may cause cancer. The National Toxicology Program, a collaborative effort between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and IARC, has developed lists of substances that are known or are reasonably anticipated to be human carcinogens based on the available scientific evidence (242)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Toxicology Program: 15th Report on Carcinogens. Accessed: July 13, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Involuntary exposures to many of the environmental pollutants are usually higher in subgroups of the population, such as workers in certain industries who may be exposed to carcinogens on the job, racial and ethnic minorities, or individuals living in poverty (13)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2022.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. As we learn more about environmental and occupational cancer risk factors and identify those segments of the U.S. population who are exposed to these factors, new and equitable policies need to be developed and implemented for the benefit of all populations.

Next Section: Screening for Early Detection Previous Section: Understanding How Cancer Develops