Screening for Early Detection

In this section, you will learn:

- Research identifying how cancer arises and progresses has led to the development of screening tests that can be used for early detection of cancer and precancerous lesions.

- There are five types of cancer (breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate) for which screening tests have been used to screen large segments of the U.S. population.

- Every person has a unique risk for each type of cancer based on genetic, molecular, and cellular makeup, lifetime exposures to cancer risk factors, and general health.

- We need to develop new strategies to ensure optimal uptake of cancer screening by all individuals.

Research continues to increase our knowledge of the causes, timing, sequence, and frequency of the genetic, molecular, and cellular changes that drive cancer initiation and development (see Understanding Cancer Development. This knowledge provides opportunities to develop screening tests that can find precancerous lesions or cancers at an early stage of development. It also provides insight into who is likely to benefit from screening and how often they should be screened.

What Is Cancer Screening and How Is It Done?

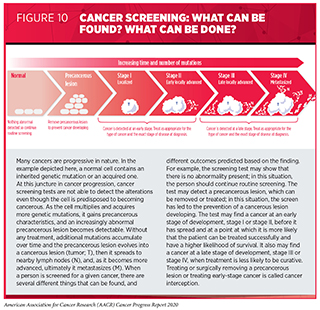

Screening for cancer means checking for precancerous lesions or cancer in people who have no signs or symptoms of the cancer for which they are being checked. The aim is to find an abnormality at the earliest possible time in cancer development. If a cancer screening test shows a precancerous lesion is present, it can be treated or surgically removed before becoming cancer (see Figure 10). If a test finds a cancer at an early stage of development, stage I or stage II, before it has spread, it is more likely that the patient can be treated successfully; for example, patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer or breast cancer when the cancer is confined to the colon or rectum, or to the breast, have 5-year relative survival rates of 90 percent and 99 percent, respectively, while those diagnosed with colorectal cancer or breast cancer that has metastasized have 5-year relative survival rates of 14 percent and 28 percent, respectively (2)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 29].. Treating or surgically removing a precancerous lesion or early-stage cancer is called cancer interception.

Screening for cancer can be done in various ways, including by using imaging technologies to look for abnormalities inside the body, and by collecting tissue or fluid samples and then analyzing them for abnormalities characteristic of the cancer being screened for (see sidebar on How Can We Screen for Cancer?). Currently, radiologists, pathologists, and other highly trained health care professionals interpret the images and/or the results of tissue or fluid sample analysis to determine whether an abnormality is present. This can be time consuming and can sometimes miss signs of cancer (false negative) or detect cancers that turn out to be false positives. Researchers have been investigating for several years whether artificial intelligence (AI) approaches can enhance the interpretation of cancer screening tests. In the 12 months covered by this report, August 1, 2019, to July 31, 2020, the FDA has cleared for clinical use several AI systems to help radiologists detect breast cancer on mammograms (277)Rodriguez-Ruiz A, Lång K, Gubern-Merida A, Broeders M, Gennaro G, Clauser P, et al. Stand-Alone Artificial Intelligence for Breast Cancer Detection in Mammography: Comparison With 101 Radiologists. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. Oxford Academic; 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 1];111:916–22.. Many more AI approaches to improving the accuracy of screening mammography and other cancer screening tests are being studied, as discussed in Looking to the Future (278)McKinney SM, Sieniek M, Godbole V, Godwin J, Antropova N, Ashrafian H, et al. International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature [Internet]. Nature Publishing Group; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];577:89–94.(279)Schaffter T, Buist DSM, Lee CI, Nikulin Y, Ribli D, Guan Y, et al. Evaluation of Combined Artificial Intelligence and Radiologist Assessment to Interpret Screening Mammograms. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];3:e200265..

Another area of research that is showing promise is the use of blood-based tests, or liquid biopsy tests, to screen for multiple types of cancer at the same time. Two research teams recently showed that this approach is feasible (280)Lennon AM, Buchanan AH, Kinde I, Warren A, Honushefsky A, Cohain AT, et al. Feasibility of blood testing combined with PET-CT to screen for cancer and guide intervention. Science (80- ) [Internet]. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];(281), but more studies are needed before these tests can be used in the clinic for routine cancer screening (see Looking to the Future).

Consensus on Cancer Screening

Screening for cancer has many benefits, including reducing the likelihood of an individual being diagnosed with the screened cancer at an advanced stage and of dying from the screened cancer (see sidebar on Cancer Screening). For example, recent data have shown that women who participated in mammography screening were 25 percent less likely to be diagnosed with advanced breast cancer and 41 percent less likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer that they would die from within 10 years of the diagnosis (282)SW D, L T, AM Y, PB D, RA S, H J, et al. Mammography Screening Reduces Rates of Advanced and Fatal Breast Cancers: Results in 549,091 Women. Cancer [Internet]. Cancer; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];126.. However, screening for cancer also has the potential to cause unintended harms, which is why it is not recommended for everyone. Determining whether and for whom a cancer screening test can provide benefits that outweigh the potential harms requires extensive research and careful analysis of the data generated.

In the United States, an independent group of experts convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services evaluates data regarding the benefits and potential harms of different approaches to disease prevention, including cancer screening tests, genetic testing, and preventive therapeutics, to make evidence-based recommendations about the use of these in the clinic. These volunteer experts form the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

The evidence-based USPSTF recommendations about cancer screening tests fall into several categories, including recommendations for screening certain individuals at certain intervals, recommendations against screening, and deciding that there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. In addition to considering evidence regarding potential new screening programs, the USPSTF reevaluates existing recommendations as new research becomes available and can revise the recommendations if necessary. For example, the USPSTF is in the process of reviewing its recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. In light of accumulating evidence that the colorectal cancer incidence rate is rising among people age 49 and younger (24)Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2020;0:1–20., one question being reviewed by the USPSTF is whether to lower the age it recommends for beginning colorectal cancer screening (see The Growing Population Burden of Cancer).

A number of professional societies also convene panels of experts to evaluate data regarding the benefits and potential harms of cancer screening tests, and each society then makes its own evidence-based recommendations about the use of these tests. Because the representatives on each panel are often different, and different groups give more weighting to certain benefits and potential harms than other groups do, this can result in differences in recommendations from distinct groups of experts. For example, for breast cancer screening, there is a difference of opinion regarding whether screening should be done every year or every other year and whether regular screening should begin at age 40, age 45, or age 50.

Differences among cancer screening recommendations from different groups of experts highlight areas in which additional research is needed to determine more clearly the relative benefits and potential harms of screening, to develop new screening tests that have clearer benefits and/or lower potential harms, or to better identify people for whom the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms.

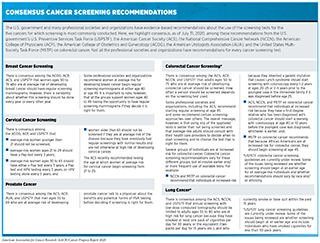

Even though there is some variability among the recommendations from different groups of experts about the use of the screening tests for the five types of cancers for which screening is most commonly conducted, overall there is more consensus than disagreement (see sidebar on Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations). Nevertheless, it can still be challenging for individuals to ascertain for which cancers to be screened for and when. One of the most important factors people should consider when making decisions about cancer screening is their risk of the cancer being screened for. Recommendations for individuals at average risk of developing a certain cancer are different from those for individuals at increased risk of developing the same cancer. Each person has his or her own unique cancer risks; therefore, people should consult with their health care providers to develop cancer screening plans that are tailored to their own risks and tolerance for the potential harms of a screening test.

For individuals at average risk of developing a cancer for which there is a screening test, age and gender are the two main characteristics used to identify those for whom screening is recommended. Age is important because cancer is predominantly a disease of aging—91 percent of U.S. cancer diagnoses occur among those age 45 and older (2)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 29].. Given that a person’s risk for most types of cancer increases with age, it is important that individuals keep up a dialog with their health care providers and continually evaluate their cancer screening plans, updating them if necessary.

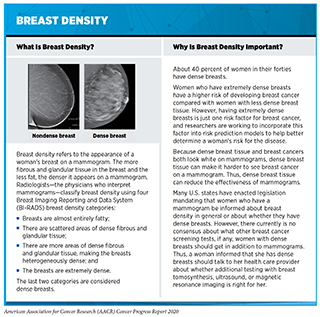

Some individuals have an increased risk of developing a certain type or types of cancer. Among the many reasons that a person might have an increased risk is through exposure to a cancer risk factor or cancer risk factors (see Preventing Cancer: Identifying Risk Factors). For example, people who smoke cigarettes are about 25 times more likely to develop lung cancer than people who do not smoke cigarettes (8). Another reason is that an individual’s unique cellular and tissue makeup might increase the risk of developing a certain type or types of cancer. For example, women who have extremely dense breasts have a higher risk of developing breast cancer compared with women with less dense breasts (284) (see sidebar on Breast Density). Yet another reason that an individual might have an increased risk of developing a certain type or types of cancer is that he or she inherited a cancer-predisposing genetic mutation (see Table 2).

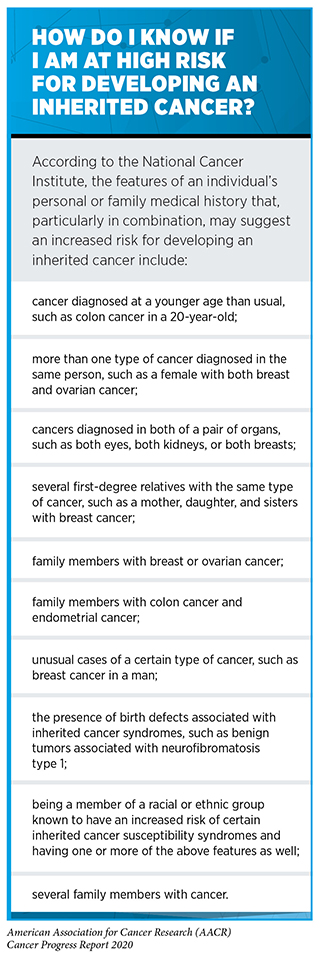

If a person thinks that he or she is at high risk for inheriting a cancer-predisposing genetic mutation, the person should consult a health care provider and consider genetic testing (see sidebar on How Do I Know If I Am at High Risk for Developing an Inherited Cancer?). As researchers learn more about inherited cancer risk (285)(286)(287)H Z, TU A, J L, D B, J B, G Q, et al. Genome-wide Association Study Identifies 32 Novel Breast Cancer Susceptibility Loci From Overall and Subtype-Specific Analyses. Nat Genet [Internet]. Nat Genet; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];52.(288)TA O, DM G, F A, D A, K A, J A, et al. Identification of Nine New Susceptibility Loci for Endometrial Cancer. Nat Commun [Internet]. Nat Commun; 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 1];9., there will be new genetic mutations to test for and changes to the recommendations about who should be offered genetic testing. For example, the USPSTF recently revised its recommendations on risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for cancer related to BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations in women, expanding the group that it recommends be screened for risk from only women who have family members with breast, ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer to women with a personal or family history of breast, ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer or an ancestry associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations (289). In addition, a group of prostate cancer experts recently recommended that men with a family history suggestive of hereditary prostate cancer should undergo testing for inherited mutations in the BRCA2 and HOXB13 genes and consider testing for inherited mutations in a larger panel of genes, including BRCA1, so as to gain information to help develop a prostate cancer screening plan tailored to the man’s genetic makeup (290)Giri VN, Knudsen KE, Kelly WK, Cheng HH, Cooney KA, Cookson MS, et al. Implementation of Germline Testing for Prostate Cancer: Philadelphia Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2019. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 3];JCO2000046..

Given that our knowledge of inherited cancer risk is continually increasing, it is important that individuals maintain an ongoing dialog with their health care provider and continually evaluate whether genetic testing is available and/or right for them. African American women are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age than white women and are more likely to be diagnosed with biologically aggressive forms of the disease at all ages. Therefore, one area of intensive research investigation is whether disparities in breast cancer outcomes for African American women can be eliminated by changing the recommendations for genetic testing based on race and/or ethnicity and by ensuring that those African American women for whom genetic testing is currently recommended undergo testing (291)JR P, EC P, C H, EM J, C H, SN H, et al. Contribution of Germline Predisposition Gene Mutations to Breast Cancer Risk in African American Women. J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. J Natl Cancer Inst; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];(292)L N. US Preventive Services Task Force Breast Cancer Recommendation Statement on Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer. JAMA Surg [Internet]. JAMA Surg; 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 1];154..

It is important to note that there are direct-to-consumer genetic tests that individuals can use without a prescription from a physician, but there are many factors to weigh when considering whether to use one of these tests. Because of the complexities of these tests, the FDA and Federal Trade Commission recommend involving a health care professional in any decision to use such testing, as well as to interpret the results.

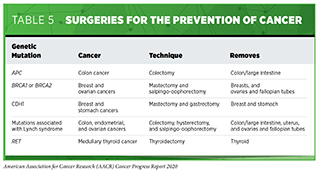

All individuals who have an increased risk of developing a certain type or types of cancer should consult with their health care providers to tailor risk-reducing measures to their personal situation. Some may be able to reduce their risk by modifying their behaviors, for example, by quitting smoking. Others might need to increase their use of certain cancer screening tests or use cancer screening tests that are not recommended for people who are at average risk for the cancer. Yet others may consider taking a preventive medicine or having risk-reducing surgery (see Table 5 and Supplemental Table 1).

As we increase our understanding of the biology of precancerous and cancerous lesions we will be able to better tailor cancer prevention and early detection to the individual patient, ushering in a new era of precision cancer prevention (294)(295). One area of interest is whether screening guidelines should differ for individuals from different racial and ethnic minority groups. For example, researchers have suggested that lung cancer screening recommendations may need to be less stringent for African Americans after it was shown that African American men have an increased risk of lung cancer despite lower pack years of smoking (296)Aldrich MC, Mercaldo SF, Sandler KL, Blot WJ, Grogan EL, Blume JD. Evaluation of USPSTF Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines Among African American Adult Smokers. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 27];5:1318.. Another area of intensive research investigation is whether cancer screening should be tailored depending on the density of a woman’s breasts because women who have dense breasts have a higher risk of developing breast cancer compared with those who have less dense breasts. Early data suggest that using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) rather than mammography or using both MRI and mammography may increase the detection of invasive breast cancer during screening of women with dense breasts (297)Bakker MF, de Lange S V., Pijnappel RM, Mann RM, Peeters PHM, Monninkhof EM, et al. Supplemental MRI Screening for Women with Extremely Dense Breast Tissue. N Engl J Med [Internet]. Massachusetts Medical Society; 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 1];381:2091–102.(298)Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, Snyder BS, Gareen IF, Bergin JT, et al. Comparison of Abbreviated Breast MRI vs Digital Breast Tomosynthesis for Breast Cancer Detection Among Women With Dense Breasts Undergoing Screening. JAMA [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];323:746., but whether this translates to reductions in deaths from breast cancer has yet to be determined. Survivors of cancer diagnosed in childhood or adolescence are another group who require carefully tailored cancer prevention and early detection plans because they are at increased risk of developing another type of cancer in adulthood and cancer is a leading cause of death among this group (299)Turcotte LM, Neglia JP, Reulen RC, Ronckers CM, Leeuwen FE van, Morton LM, et al. Risk, Risk Factors, and Surveillance of Subsequent Malignant Neoplasms in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Review. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 1];36:2145.(300)Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, Leisenring W, Gibson TM, Mertens AC, et al. Reduction in Late Mortality among 5-Year Survivors of Childhood Cancer. N Engl J Med [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2016 [cited 2019 Jun 20];374:833–42.(see Supporting Cancer Patients and Survivors).

Suboptimal Use of Cancer Screening Tests

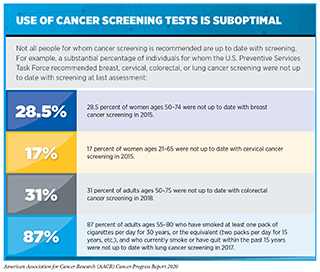

Even though the benefits of screening for breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancer outweigh the potential risks for defined groups of individuals (see sidebar on Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations), many of those for whom screening is recommended do not get screened (see sidebar on Use of Cancer Screening Tests is Suboptimal). Individuals who are not up to date with cancer screening recommendations are disproportionately found in medically underserved segments of the U.S. population (see sidebar on Disparities in Cancer Screening).

In addition to suboptimal uptake among those individuals for whom screening is recommended, some people for whom screening is not recommended, such as individuals below or above the recommended age range for a given cancer screening test and those with limited life expectancy, are screened even though the evidence indicates that the benefits of screening are unlikely to outweigh the potential harms for them (304)Qin J, Saraiya M, Martinez G, Sawaya GF. Prevalence of Potentially Unnecessary Bimanual Pelvic Examinations and Papanicolaou Tests Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women Aged 15-20 Years in the United States. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];180:274.(305)Calderwood AH, Anderson JC, Robinson CM, Butterly LF. Endoscopist Specialty Predicts the Likelihood of Recommending Cessation of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Older Adults. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 20];113:1862–71.(306)Schoenborn NL, Huang J, Sheehan OC, Wolff JL, Roth DL, Boyd CM. Influence of Age, Health, and Function on Cancer Screening in Older Adults with Limited Life Expectancy. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 20];34:110–7..

The suboptimal use of cancer screening tests and the significant disparities in cancer screening rates among certain segments of the U.S. population highlight the need for new strategies and public policies to increase cancer screening awareness, access, and uptake among those for whom screening is recommended. Actively reaching out and providing individuals with culturally sensitive information can help optimize use of cancer screening tests (307)Schonberg MA, Kistler CE, Pinheiro A, Jacobson AR, Aliberti GM, Karamourtopoulos M, et al. Effect of a Mammography Screening Decision Aid for Women 75 Years and Older. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];180:831.)(308)Rice K, Gressard L, DeGroff A, Gersten J, Robie J, Leadbetter S, et al. Increasing colonoscopy screening in disparate populations: Results from an evaluation of patient navigation in the New Hampshire Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Cancer [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jun 20];123:3356–66.(309)Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, Gupta S, Wheeler SB, Coker-Schwimmer M, et al. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];178:1645–58.(310)Liu D, Schuchard H, Burston B, Yamashita T, Albert S. Interventions to Reduce Healthcare Disparities in Cancer Screening Among Minority Adults: a Systematic Review. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];. This can be done in the form of mailing information to individuals, as exemplified by the reduction in the number of women above the USPSTF-recommended cut-off age for breast cancer screening—those age 75 and older—who underwent breast cancer screening after receiving a pamphlet about mammography before they visited their doctor (307)Schonberg MA, Kistler CE, Pinheiro A, Jacobson AR, Aliberti GM, Karamourtopoulos M, et al. Effect of a Mammography Screening Decision Aid for Women 75 Years and Older. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];180:831.. It can also be done through patient navigation programs that provide individualized assistance to help patients overcome personal and health care system barriers, and to facilitate understanding and timely access to screening (308)Rice K, Gressard L, DeGroff A, Gersten J, Robie J, Leadbetter S, et al. Increasing colonoscopy screening in disparate populations: Results from an evaluation of patient navigation in the New Hampshire Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Cancer [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jun 20];123:3356–66.(309)Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, Gupta S, Wheeler SB, Coker-Schwimmer M, et al. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];178:1645–58.(310)Liu D, Schuchard H, Burston B, Yamashita T, Albert S. Interventions to Reduce Healthcare Disparities in Cancer Screening Among Minority Adults: a Systematic Review. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 1];. Another approach that has been shown to successfully increase colorectal and cervical cancer screening rates is to mail individuals a stool test or an HPV kit, respectively, that allows people to take their own sample at home (309)Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, Gupta S, Wheeler SB, Coker-Schwimmer M, et al. Evaluation of Interventions Intended to Increase Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in the United States: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];178:1645–58.(311)RL W, J L, JA T, DL M, T B, H G, et al. Effect of Mailed Human Papillomavirus Test Kits vs Usual Care Reminders on Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake, Precancer Detection, and Treatment: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw open [Internet]. JAMA Netw Open; 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 1];2..

Federal agencies and the federal government also have a role to play in optimizing cancer screening (see Advancing Effective Cancer Prevention, Treatment, and Control Efforts). For example, the NCI and CDC support numerous programs that help provide resources, materials, and infrastructure for outreach and education, and that increase access and utilization of cancer screening services. In addition, the Affordable Care Act requires Marketplace plans to provide without cost-sharing colorectal cancer screening for adults ages 50 to 75, tobacco use screening, and lung cancer screening for adults ages 55 to 80 who are at high risk for lung cancer (www.healthcare.gov/preventive-care-adults/). Research suggests that by eliminating out-of-pocket costs for preventive colonoscopies, the Affordable Care Act has reduced disparities in colorectal cancer screening (312)A H, SS H, LE P, J C. Rural-urban Disparities in Colonoscopies After the Elimination of Patient Cost-Sharing by the Affordable Care Act. Prev Med (Baltim) [Internet]. Prev Med; 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 1];129., but other approaches are needed to fully optimize the use of cancer screening tests.