Special Feature on Disparities in COVID-19 and Cancer

In this section you will learn:

- On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a global pandemic.

- As of July 31, 2020, there have been 17,622,478 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 680,165 deaths from the disease globally; there have been 4,566,275 cases and 153,391 deaths in the United States.

- Older adults, males, and individuals of any age with certain underlying medical conditions are at an increased risk for severe COVID-19 illness.

- Racial and ethnic minorities have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 for many of the same reasons that they shoulder a disproportionate burden of cancer.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted cancer care for many people, causing concern that the delays in screening, diagnosis, and treatment will exacerbate cancer health disparities in the future.

- All stakeholders need to work together to identify innovative mechanisms to reduce COVID-19 disparities and make strides in the future toward eliminating all health disparities, including cancer health disparities.

In 2020, a disease termed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), spread rapidly around the world. On March 11, 2020, World Health Organization (WHO) declared the ensuing global health crisis a pandemic.

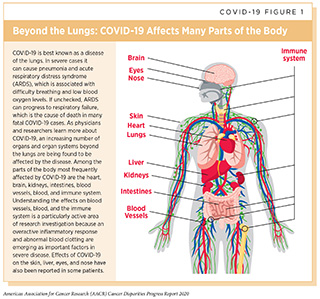

As of July 31, 2020, more than 17 million people worldwide were diagnosed with COVID-19 and more than 680,000 people died from the disease, which affects many organs of the body in addition to the lungs (1)COVID-19 Map – Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 15].(2)Gupta A, Madhavan M V., Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2020 Jul 15];26(7):1017–32. (see COVID-19 Figure 1). Beyond this personal toll, the COVID-19 pandemic has overwhelmed health care systems, devastated societal norms, and shattered the economies of U.S. households as well as those of other nations.

In the United States, which accounts for more than one in every four recorded cases of COVID-19 and almost one in every four recorded deaths from the disease (1)COVID-19 Map – Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 15]., the burden of the disease has not been shouldered equally by all segments of the population (see sidebar on Disparities in the Burden of COVID-19 in the United States). As with cancer, a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 has fallen on racial and ethnic minorities, in particular, African Americans and Hispanics (4)COVID-19 Data from the National Center for Health Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 15].(5)Wortham JM, Lee JT, Althomsons S, Latash J, Davidson A, Guerra K, et al. Characteristics of Persons Who Died with COVID-19 — United States, February 12–May 18, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2020 Jul 15];69(28)..

Why Do COVID-19 Disparities Exist?

Researchers are actively working to identify the specific factors contributing to the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 among racial and ethnic minorities. Early data suggest that there are several complex and interrelated factors, some of which overlap with the factors that contribute to cancer health disparities (10)Bibbins-Domingo K. This Time Must Be Different: Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16];(11)Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 May 11 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; (see Why Do Cancer Health Disparities Exist?).

Social determinants of health, defined by the NCI as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, are emerging as some of the most important factors contributing to racial and ethnic COVID-19 disparities (10)Bibbins-Domingo K. This Time Must Be Different: Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16];(11)Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 May 11 [cited 2020 Jul 16];(12)Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 Apr 15 [cited 2020 Jul 16];. People in racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to live in conditions that pose challenges for social distancing, which is one of the main strategies for reducing infection with SARS-CoV-2. For example, they are more likely to live in lower-income apartment complexes, with higher numbers of occupants per unit, and more likely to live in multigenerational family units. The same people are also more likely to work in occupations considered essential for society to function—such as staffing grocery stores, hospitals, and nursing homes; building maintenance; public transportation; and delivery services—which increases their chances of being exposed to SARS-CoV-2 because they are unable to shelter at home (13)U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2018. BLS Reports [Internet]. 2019;(October):1–101.(14)(15)Donovan SA, Labonte M, Dalaker J. The U.S. Income Distribution: Trends and Issues. 2016;47.. In addition, people in racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to have jobs that may not provide a secure income, only paying if the individual shows up to work, which means that they are more likely to leave their home, increasing the chance of exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

Another important factor contributing to racial and ethnic COVID-19 disparities is that many people in racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to have one or more of the health conditions discovered to increase a person’s chance of severe COVID-19 compared with non-Hispanic whites (10)Bibbins-Domingo K. This Time Must Be Different: Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16];(11)Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 May 11 [cited 2020 Jul 16];(12)Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 Apr 15 [cited 2020 Jul 16];(16)Hsu HE, Ashe EM, Silverstein M, Hofman M, Lange SJ, Razzaghi H, et al. Race/Ethnicity, Underlying Medical Conditions, Homelessness, and Hospitalization Status of Adult Patients with COVID-19 at an Urban Safety-Net Medical Center – Boston, Massachusetts, 2. Among the health conditions that can increase a person’s risk of severe illness from infection with SARS-CoV-2 are chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obesity, heart failure, coronary artery disease, sickle cell disease, diabetes, and having a weakened immune system (17)People Who Are at Higher Risk for Severe Illness | Coronavirus | COVID-19 | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 16].. Other health conditions, including asthma and high blood pressure, have also been linked to an increased risk of severe COVID-19, but additional research is needed to confirm these associations.

Inequity in access to quality health care is a key factor contributing to the higher levels of underlying health conditions that increase risk of severe COVID-19 among people in racial and ethnic minority groups. It is anticipated that we will find that disparities in access to quality health care are also directly contributing to the higher COVID-19 mortality among people in racial and ethnic minority groups, but additional research on this topic is needed (10)Bibbins-Domingo K. This Time Must Be Different: Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16];. In addition, there is deep concern that undocumented immigrants will experience adverse differences in COVID-19 measures, in large part because of a lack of access to quality health care (18)Koven S. Undocumented U.S. Immigrants and Covid-19. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020;62(1):1–2..

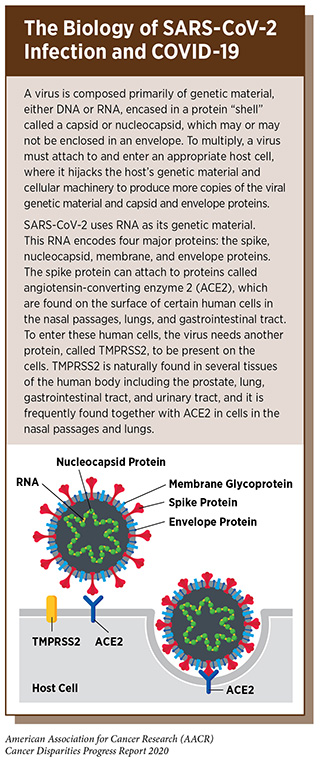

Researchers are actively investigating whether there are biological and/or genetic factors contributing to racial and ethnic COVID-19 disparities. To conduct this research, it was first necessary to study the biology of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 (see sidebar on The Biology of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19). The knowledge gained from these studies has focused disparities research on two proteins that are critical for SARS-CoV-2 infection of human cells—angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and TMPRSS2—and on the immune response that is thought to cause the severe lung disease seen in patients with COVID-19 (19)Tal Y, Adini A, Eran A, Adini I. Racial disparity in Covid-19 mortality rates – A plausible explanation. Clin Immunol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 16];217:108481.. One study found that among people with asthma, those who are African American, as well as those who have diabetes, have higher levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 on cells in their lungs compared with those of who are from other racial and ethnic groups (20)Peters MC, Sajuthi S, Deford P, Christenson S, Rios CL, Montgomery MT, et al. COVID-19–related Genes in Sputum Cells in Asthma. Relationship to Demographic Features and Corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2020 Jul 16];. Additional research is needed to determine whether these observations are also true in individuals who do not have asthma and whether they are linked to differences in the severity of COVID-19 in different populations groups. In addition, cancer research has shown that the TMPRSS2 gene is altered in a high proportion of prostate cancers, and that there are racial and ethnic differences in the frequency of these genetic alterations (21)Stopsack KH, Mucci LA, Antonarakis ES, Nelson PS, Kantoff PW. TMPRSS2 and COVID-19: Serendipity or Opportunity for Intervention? Cancer Discov [Internet]. 2020 Apr 10 [cited 2020 Jul 16];10(6):779–82.. Establishing whether this has any relation to disparities in COVID-19 and whether it might be possible to harness knowledge of TMPRSS2 gained through cancer-focused research to reduce COVID-19 disparities are areas of interest to researchers.

Only with increased understanding of the factors that contribute to COVID-19 disparities will we be able to address the devastating impact of COVID-19 among racial and ethnic minorities.

Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 Testing

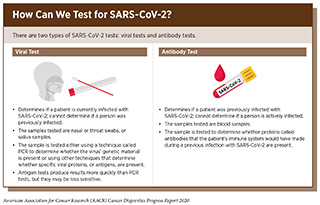

Timely testing to identify those who are or have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 is a crucial step in understanding and controlling the COVID-19 pandemic (see sidebar on How Can we Test for SARS-CoV-2?). Without knowledge of who is infected, it is challenging to implement appropriate measures to prevent further spread of the virus and to understand when such measures can be eased.

In the United States, SARS-CoV-2 testing was not readily available to anyone during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (22)Cohen J. The United States badly bungled coronavirus testing—but things may soon improve. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 2020 Feb 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16];(23)Servick K. ‘Huge hole’ in COVID-19 testing data makes it harder to study racial disparities. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2020 Jul 16];. Even as things have slowly improved, evidence suggests that many people in racial and ethnic minority groups have had less access to testing compared with whites. Fortunately, efforts to increase access are underway. One of the barriers to testing for people in racial and ethnic minority groups has been that testing sites were often located in neighborhoods in which the majority of residents are white, although recognition of this is growing and many states and cities, including Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, are actively working to address this issue (24)COVID-19 Racial Disparities Could Be Worsened By Location Of Test Sites : Shots – Health News : NPR [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 16].(25)Bilal U, Barber S, Diez-Roux A V. Spatial Inequities in COVID-19 outcomes in Three US Cities. medRxiv [Internet]. 2020;2020.05.01.20087833.. Another barrier is that in some places, individuals initially needed a referral from a health care provider to be tested for SARS-CoV-2, and people in racial and ethnic minority groups are less likely to have a regular health care provider. Fortunately, recognition of this issue is growing and criteria for testing are being relaxed in some areas. For example, initially, the citywide testing that was made available in Detroit at the State Fairgrounds was limited to those who had a physician’s order; later, as testing capacity improved, testing became available to those without such an order (26)Detroit Expands COVID-19 Testing to All City Residents | WDET [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 16].. Other barriers to access to SARS-CoV-2 testing are harder to address as they include social and behavioral factors such as distrust in the health care system, fear of medical costs, language barriers, and lack of paid sick leave if a test indicates SARS-CoV-2 infection (11)Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 May 11 [cited 2020 Jul 16];.

Addressing disparities in SARS-CoV-2 testing is critical to control the spread of the virus in racial and ethnic minority communities. However, there is also an urgent need for resources to support individuals in these communities who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 because such a diagnosis would make these individuals vulnerable to subsequent social and health care disparities.

COVID-19 and Cancer Health Disparities

The COVID-19 pandemic has created many challenges across the continuum of cancer care, with deep concern about the consequences that delays in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment will have on outcomes for patients with cancer (27)Sharpless NE. COVID-19 and cancer. Science [Internet]. 2020 Jun 19 [cited 2020 Jun 29];368(6497):1290.(28)Hoehn RS, Zureikat AH. Cancer disparities in the COVID-19 era. J Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2020 May 25 [cited 2020 Jul 16];. Data from electronic medical records from 190 hospitals spanning 23 states show that the number of screening tests for early detection of cervical, breast, and colon cancer conducted in the United States plummeted by 85 percent or more after the first COVID-19 case was reported in the United States on January 20, 2020 (29)EPIC Health Research Network. Preventive Cancer Screenings during COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020;1–5., and a recent survey of patients with cancer found that 79 percent of those who are actively undergoing treatment had to delay some aspect of their care as a result of COVID-19, including 17 percent who reported delays to their cancer treatment (30)Cancer Action Netwrok. COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Cancer Patients and Survivors: Survey Findings Summary. 2020;1–5.. It will take years to determine the consequences of all the delays, but researchers at the NCI have estimated that there will be at least 10,000 additional deaths from breast cancer and colorectal cancer over the next decade in the United States as a result of the negative impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on screening and treatment for these two types of cancer (27)Sharpless NE. COVID-19 and cancer. Science [Internet]. 2020 Jun 19 [cited 2020 Jun 29];368(6497):1290..

There are many reasons for the delays in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment that have been reported, including the need to focus health care resources on COVID-19–related emergency medicine and critical care services, the need to support shelter-in-place and social distancing policies implemented to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2, and fear of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 when leaving the home to receive health care. In addition, for cancer treatment, many delays were the result of efforts to reduce the risk of patients with cancer becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 as they go to a health care provider to receive treatment. This is a concern because early data from China, and the United States indicate that patients with cancer are more likely to die from COVID-19 if they become infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared with individuals who do not have cancer (31)Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, Cole D, Goldfinger M, Acuna-Villaorduna A, et al. Case Fatality Rate of Cancer Patients with COVID-19 in a New York Hospital System. Cancer Discov [Internet]. 2020 May 1 [cited 2020 Jul 16];10(7):935–41.(32)Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, Zhou F, Li G, Chen Z, et al. Patients with Cancer Appear More Vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: A Multicenter Study during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Cancer Discov [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16];10(6):783–91.(33)Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Factors Associated With Death in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2020 Jul 15 [cited 2020 Jul 16];. Another report on outcomes following surgery found that lung complications occurred in 50 percent of all patients undergoing surgery who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 around the time of the surgery and that 24 percent died within 30 days of surgery (34). These numbers are dramatically higher than normally expected, and have led to delays in surgery, including surgeries for cancer.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, most cancer centers have been testing all patients for active SARS-CoV-2 infection before surgery, radiation therapy, or systemic therapy. The logistics of cancer care have also been greatly affected. Caring for someone with cancer who has symptoms suggesting infection requires specialized facilities for the isolation of persons known or suspected to have COVID-19. These specialized facilities are needed both for COVID-19 testing and for the timely delivery of urgent care that might be needed to treat cancer or the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Even routine care for patients with cancer who do not have COVID-19 has changed dramatically. To accomplish a measure of social distancing, many in-person health care visits have been replaced by video visits and telemedicine.

There is an urgent need for rigorous studies investigating how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected cancer health disparities. However, experts predict that the pandemic will exacerbate existing disparities. People in racial and ethnic minority groups already experience inequalities in socioeconomic status that contribute to cancer health disparities (see Social Factors Contributing to Cancer Health Disparities). The COVID-19 pandemic has caused U.S. unemployment rates to skyrocket and people in racial and ethnic minority groups have been disproportionately represented among jobs that have been lost (13)U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2018. BLS Reports [Internet]. 2019;(October):1–101.(14)(15)Donovan SA, Labonte M, Dalaker J. The U.S. Income Distribution: Trends and Issues. 2016;47.. In addition to loss of income, unemployment can lead to loss of health insurance and tends to make general health care a lower priority in comparison to other costs of living such as meals and housing. This has the potential to drastically reduce cancer screening for early detection among people in racial and ethnic minority groups, which in turn increases the likelihood of any cancer being identified at an advanced stage, when it is less likely to be treated successfully. This also has the potential to intensify disparities in treatment and other aspects of cancer care.

Another factor that is likely to compound existing cancer health disparities is that the public hospitals that provide safety-net heath care and general medical care, including cancer care, to a disproportionate volume of people in racial and ethnic minority groups have been hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic (16)Hsu HE, Ashe EM, Silverstein M, Hofman M, Lange SJ, Razzaghi H, et al. Race/Ethnicity, Underlying Medical Conditions, Homelessness, and Hospitalization Status of Adult Patients with COVID-19 at an Urban Safety-Net Medical Center – Boston, Massachusetts, 2. The economic impact of the pandemic on these already financially constrained health care systems has the potential to further compromise cancer care for racial and ethnic minorities. In addition, people in racial and ethnic minority groups are less likely to have the capability for using advanced communication technologies for telemedicine, further limiting access to health care.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a negative impact on individuals, communities, and health care systems across the United States and around the world. In the post-COVID era, there will be an urgent need to ensure comprehensive health care and economic interventions for equitable recovery of cancer care, from prevention, to early detection, diagnosis, and treatment, to survivorship care.

COVID-19 Disparities: A Window of Opportunity to Achieve the Bold Vision of Health Equity?

The COVID-19 pandemic has focused national attention on the issue of health disparities. Racial and ethnic minority groups within the U.S. population have shouldered a disproportionate burden of the disease, and there is immense concern that the pandemic will exacerbate other existing health disparities, including cancer health disparities. It is imperative that all stakeholders work together to galvanize the momentum that has been created by the pandemic and by the current movement against racial inequality to reduce the unequal burden of all diseases, including COVID-19 and cancer.

Currently, addressing health disparities related to the COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most urgent public health challenges in the United States. The many steps that need to be taken to reduce COVID-19 disparities are:

- Health insurance coverage opportunities such as expanded Medicaid programs should be made readily available to financially constrained individuals who lost their employment-based health insurance because of the COVID-19 pandemic and to undocumented immigrants.

- Public hospitals must be supported so that they can continue to meet the safety-net health care needs of communities that are disproportionately represented among the medically underserved, including racial and ethnic minorities.

- Public health and educational messages tailored to racial and ethnic minority groups must be developed and implemented to increase COVID-19 testing among these segments of the population.

- Clinical trials testing COVID-19 diagnostic tests, treatments, and vaccines must have adequate representation of racial and ethnic minorities.

- Basic research into COVID-19 should be designed a priori with disparities-related studies, such as understanding viral biology in diverse host environments in terms of inherited genetic architecture as well as relevant acquired phenotypes (e.g. metabolic syndrome) that result from exposure to different physical environments.

It is imperative that all stakeholders build upon the concerted efforts to address COVID-19 disparities and drive progress in eliminating all health disparities, including cancer disparities, in the future. As the cancer research community recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is vital that cancer health disparities research, including community outreach, education, and engagement efforts, is protected from any budget constraints that arise as a result of the adverse financial impact of the pandemic.

Special Feature References

- COVID-19 Map – Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Gupta A, Madhavan M V., Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2020 Jul 15];26(7):1017–32. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-0968-3

- Wadman M. How does coronavirus kill? Clinicians trace a ferocious rampage through the body, from brain to toes. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 2020 Apr 17 [cited 2020 Jul 15]; Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/how-does-coronavirus-kill-clinicians-trace-ferocious-rampage-through-body-brain-toes

- COVID-19 Data from the National Center for Health Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/index.htm

- Wortham JM, Lee JT, Althomsons S, Latash J, Davidson A, Guerra K, et al. Characteristics of Persons Who Died with COVID-19 — United States, February 12–May 18, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2020 Jul 15];69(28). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6928e1.htm?s_cid=mm6928e1_w

- Bureau UC. National Population by Characteristics: 2010-2019. [cited 2020 Jan 22]; Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html

- Covid-19 in racial and ethnic minority groups [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html?deliveryName=USCDC_2067-DM26555

- Stokes EK, Zambrano LD, Anderson KN, Marder EP, Raz KM, El Burai Felix S, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Case Surveillance – United States, January 22-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(24):759–65.

- Facts ME. Preliminary Medicare COVID-19 Data Snapshot Preliminary Medicare COVID-19 Data Snapshot. 2020;(April):1–12.

- Bibbins-Domingo K. This Time Must Be Different: Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32343767

- Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 May 11 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32391864

- Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA [Internet]. 2020 Apr 15 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32293639

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2018. BLS Reports [Internet]. 2019;(October):1–101. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

- THE U.S. LABOR MARKET DURING THE BEGINNING OF THE PANDEMIC RECESSION. Dk. 2015;53(9):1689–99.

- Donovan SA, Labonte M, Dalaker J. The U.S. Income Distribution: Trends and Issues. 2016;47. Available from: www.crs.gov

- Hsu HE, Ashe EM, Silverstein M, Hofman M, Lange SJ, Razzaghi H, et al. Race/Ethnicity, Underlying Medical Conditions, Homelessness, and Hospitalization Status of Adult Patients with COVID-19 at an Urban Safety-Net Medical Center – Boston, Massachusetts, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2020;69(27):864–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32644981

- People Who Are at Higher Risk for Severe Illness | Coronavirus | COVID-19 | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fneed-extra-precautions%2Fgroups-at-higher-risk.html

- Koven S. Undocumented U.S. Immigrants and Covid-19. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2020;62(1):1–2. Available from: nejm.org

- Tal Y, Adini A, Eran A, Adini I. Racial disparity in Covid-19 mortality rates – A plausible explanation. Clin Immunol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 16];217:108481. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32473354

- Peters MC, Sajuthi S, Deford P, Christenson S, Rios CL, Montgomery MT, et al. COVID-19–related Genes in Sputum Cells in Asthma. Relationship to Demographic Features and Corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2020 Jul 16];202(1):83–90. Available from: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.202003-0821OC

- Stopsack KH, Mucci LA, Antonarakis ES, Nelson PS, Kantoff PW. TMPRSS2 and COVID-19: Serendipity or Opportunity for Intervention? Cancer Discov [Internet]. 2020 Apr 10 [cited 2020 Jul 16];10(6):779–82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32276929

- Cohen J. The United States badly bungled coronavirus testing—but things may soon improve. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 2020 Feb 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/02/united-states-badly-bungled-coronavirus-testing-things-may-soon-improve

- Servick K. ‘Huge hole’ in COVID-19 testing data makes it harder to study racial disparities. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 2020 Jul 10 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; Available from: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/07/huge-hole-covid-19-testing-data-makes-it-harder-study-racial-disparities

- COVID-19 Racial Disparities Could Be Worsened By Location Of Test Sites : Shots – Health News : NPR [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/05/27/862215848/across-texas-black-and-hispanic-neighborhoods-have-fewer-coronavirus-testing-sit

- Bilal U, Barber S, Diez-Roux A V. Spatial Inequities in COVID-19 outcomes in Three US Cities. medRxiv [Internet]. 2020;2020.05.01.20087833. Available from: http://medrxiv.org/content/early/2020/05/27/2020.05.01.20087833.abstract

- Detroit Expands COVID-19 Testing to All City Residents | WDET [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 16]. Available from: https://wdet.org/posts/2020/05/19/89630-detroit-expands-covid-19-testing-to-all-city-residents/

- Sharpless NE. COVID-19 and cancer. Science [Internet]. 2020 Jun 19 [cited 2020 Jun 29];368(6497):1290. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32554570

- Hoehn RS, Zureikat AH. Cancer disparities in the COVID-19 era. J Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2020 May 25 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32452031

- EPIC Health Research Network. Preventive Cancer Screenings during COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020;1–5. Available from: https://www.ehrn.org/wp-content/uploads/Preventive-Cancer-Screenings-during-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf

- Cancer Action Netwrok. COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Cancer Patients and Survivors: Survey Findings Summary. 2020;1–5. Available from: https://www.fightcancer.org/releases/survey-covid-19-affecting-patients’-access-cancer-care-7

- Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, Cole D, Goldfinger M, Acuna-Villaorduna A, et al. Case Fatality Rate of Cancer Patients with COVID-19 in a New York Hospital System. Cancer Discov [Internet]. 2020 May 1 [cited 2020 Jul 16];10(7):935–41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32357994

- Dai M, Liu D, Liu M, Zhou F, Li G, Chen Z, et al. Patients with Cancer Appear More Vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: A Multicenter Study during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Cancer Discov [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2020 Jul 16];10(6):783–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32345594

- Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Factors Associated With Death in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2020 Jul 15 [cited 2020 Jul 16]; Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2768602

- Archer JE, Odeh A, Ereidge S, Salem HK, Jones GP, Gardner A, et al. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;9–11.