Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce

In this section you will learn:

- A lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the pool of well-prepared trainees and well-trained researchers, and a lack of diversity in the health care workforce, contribute to cancer health disparities.

- Over the past two decades, diversity-focused training and career development programs have enhanced racial and ethnic diversity in cancer training, although gaps remain throughout the trajectory of the training path.

- Racial and ethnic minorities continue to be seriously underrepresented in the cancer research and cancer care workforce.

- Training and workforce diversity must remain a high priority if we are to eliminate cancer health disparities and, ultimately, realize the goal of achieving health equity.

The causes of cancer health disparities are complex and multifactorial, including interrelated biological, social, economic, cultural, environmental, behavioral, and clinical factors (see Why Do Cancer Health Disparities Exist?). Another important factor that contributes to cancer health disparities is the lack of diversity in the pool of well-prepared trainees and well-trained researchers, and the lack of diversity in the health care workforce. Given that diversity can be defined as the full range of human similarities and differences in group affiliation including gender, race and ethnicity, social class, role within an organization, age, religion, sexual orientation, physical ability, and other group identities (353)Dreachslin JL. Conducting effective focus groups in the context of diversity: theoretical underpinnings and practical implications. Qual Health Res [Internet]. Sage PublicationsSage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA; 1998 [cited 2019 Dec 18];8:813–20.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., it is clear that everyone must work together to achieve the bold vision of health equity.

Building a diverse cancer research community and biomedical workforce depends on a strong foundation in training and education. Diversity in cancer training, and by extension the workforce, helps ensure the inclusion of new viewpoints, enhances innovation and creativity, and has the potential to assist in addressing cancer health disparities (354)Rock D, Grant H. Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter. Harvard Bus Rev Digit Artic. 2016;p2-4. 3p.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(355)Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority Physicians’ Role in the Care of Underserved Patients. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 18];174:289.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(356)Hunt V, Prince S, Dixon-Fyle S, Yee L. Delivering through Diversity. Mckinsey Co [Internet]. 2018;42.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Many of the population groups that bear a disproportionate burden of cancer are also significantly underrepresented in the U.S. biomedical research and health care workforce. Increasing representation of racial and ethnic minorities will ensure that the training pipeline and biomedical workforce are more representative of our increasingly diverse nation and the populations enduring the unequal burden of cancer, and, by extension, that progress resulting from cancer research will reach all populations. Training and workforce diversity have a dynamic and bidirectional relationship that is required to ensure that disparities in cancer are reduced or eliminated (see Figure 14). Moreover, a cancer research workforce that reflects its communities ensures an environment for advancing cancer health equity.

With at least 90 percent of the U.S. population growth between 2010 and 2050 expected to come from racial and ethnic minority groups, the issue of training and workforce diversity is more urgent than ever (357)National Conference of State Legislatures. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities: Workforce Diversity. 2014;1–3.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Here we focus on the disparities among African Americans and Hispanics in the cancer workforce. We explore the current landscape of training and workforce diversity and provide recommendations that envision how we can best achieve a cancer research training pool and health care workforce that mirror the diversity of our communities.

Diversity in Cancer Training

The traditional academic pipeline—starting with K–12 education, through undergraduate and graduate programs, followed by postdoctoral or clinician training, and leading to an independent investigator (including physician-scientist) position—is far from linear.

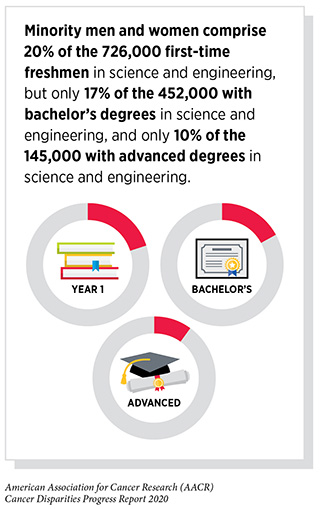

Cancer Training Landscape

In the current landscape, underrepresented racial and ethnic minority students do not have opportunities to engage and advance at pivotal points along the training path, from precollege education, through transitioning to and completing college, enrolling in graduate programs, and participating in postdoctoral and early investigator training (358)Heggeness ML, Evans L, Pohlhaus JR, Mills SL. Measuring Diversity of the National Institutes of Health-Funded Workforce. Acad Med [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 27];91:1164–72.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(358)Heggeness ML, Evans L, Pohlhaus JR, Mills SL. Measuring Diversity of the National Institutes of Health-Funded Workforce. Acad Med [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 27];91:1164–72.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Consequently, between 2000 and 2018, graduation rates for white and Asian students were higher than for African American students. In addition, the disparity between whites and African Americans in their late twenties who had attained a bachelor’s or higher degree widened over this time period, from 16 to 21 percentage points (360)The Condition of Education – Population Characteristics and Economic Outcomes – Population Characteristics – Educational Attainment of Young Adults – Indicator May (2019) [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 18].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These persistent gaps throughout the trajectory of the training path culminate in low representation at the transition into the workforce (361)Valantine HA, Lund PK, Gammie AE. From the NIH: A Systems Approach to Increasing the Diversity of the Biomedical Research Workforce. CBE Life Sci Educ [Internet]. American Society for Cell Biology; 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 27];15.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(360)The Condition of Education – Population Characteristics and Economic Outcomes – Population Characteristics – Educational Attainment of Young Adults – Indicator May (2019) [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 18].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

To promote cancer research training for diverse populations, CRCHD developed and implemented the Continuing Umbrella of Research Experiences (CURE) program (see Figure 15). CURE, which supports underrepresented racial and ethnic minority trainees and scientists, employs a holistic approach that promotes mentoring, professional support, and career skills building, all surrounding the centerpiece of individually mentored research experience. To date, CURE has supported over 4,000 students and scientists from middle school to the early investigator level.

Over the past two decades, many diversity-focused training and career development programs (both federally and privately funded) have been instituted in response to the urgent need to enhance workforce diversity. These programs have been successful and impactful in advancing diversity in cancer training, while also identifying areas for improvement such as the following:

- Narrow academic and career-level focus: most programs focus on one part of the training path (e.g. undergraduate), with no clear strategies to connect students to subsequent career levels.

- Broad population approach: most programs seek to support all underrepresented minority populations, which may neglect to address the specific needs of a particular population.

- Inconsistent program access and support: many programs are concentrated in resource-rich geographic locations and institutions, whereas fewer are found in geographic areas and institutions accessible to underserved populations. Few programs offer intense support including mentoring, didactic courses, career skills building, and other professional development opportunities, while many only provide funding for research experiences.

- Lack of data evidence: evaluation of programs and tracking of trainees vary widely between programs. Almost all programs have anecdotal stories, but few have longitudinal and quantitative data to demonstrate impact.

Fostering racial and ethnic diversity among trainees requires a robust ecosystem of support that is flexible, inclusive, and individualized. Moving into the next decade, in place of the traditional pipeline, cancer research training can be envisioned as a tree in which a diverse cadre of scientists draws nourishment from strong support systems and flourishes into different branches of academic and career achievements (see Figure 16). Taking the foregoing population- and programmatic-level factors into consideration, several actions are needed to meaningfully strengthen diversity in training (see sidebar on Recommendations for a Strong and Diverse Trainee Pipeline).

Diversity in the Cancer Workforce

The U.S. health care workforce comprises individuals with earned degrees employed in a variety of career sectors, including research scientists working in colleges and universities, biotechnology and pharmaceutical industrial settings, and government laboratories; those caring for patients, including physicians, physician-scientists, nurses, nurse practitioners, promotoras, community health educators, and patient navigators; advocates and community-based organizations; and those in science policy and regulatory policy and science communications.

Enhancing racial and ethnic diversity in the health care workforce is critically important for many reasons. Such a diverse workforce increases the likelihood of better care for racial and ethnic minority and other underserved groups, including Medicaid patients and the uninsured; improves patient-physician relationships through greater communication, linguistic concordance, and cultural competence; and results in greater patient adherence and satisfaction with care (363)Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, Vranizan K, Lurie N, Keane D, et al. The Role of Black and Hispanic Physicians in Providing Health Care for Underserved Populations. N Engl J Med [Internet]. Massachusetts Medical Society ; 1996 [cited 2019 Dec 18];334:1305–10.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(364)Graziani GC, Augenblick N, Bulow J, Casey K, Chandrasekhar A, Chetty R, et al. Does Diversity Matter For Health? Am Econ Rev [Internet]. 2019;109:4071–111.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(365)Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, et al. Race, Gender, and Partnership in the Patient-Physician Relationship. JAMA [Internet]. American Medical Association; 1999 [cited 2019 Dec 18];282:583.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, underrepresented racial and ethnic minority women resolved breast cancer and cervical cancer screening abnormalities in a timelier fashion when working with race-concordant and linguistically concordant patient navigators (366)Charlot M, Santana MC, Chen CA, Bak S, Heeren TC, Battaglia TA, et al. Impact of patient and navigator race and language concordance on care after cancer screening abnormalities. Cancer [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 18];121:1477–83.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Diversity in the workforce can also mean that implicit biases are less likely to persist, cultural incompetence is less likely to compromise care, and systemic disparities are less likely to become ingrained (see Table 8). In the context of clinical research, workforce diversity can advance underrepresented minority participation by fostering credibility and making certain that research is culturally competent (367)Noah BA. The Participation of Underrepresented Minorities in Clinical Research [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2019 Dec 18].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Cancer Workforce Landscape

Today, racial and ethnic minorities continue to be seriously underrepresented in the cancer research and care workforce, yet they are the most rapidly growing segment of the U.S. population (368)Dall T, Reynolds R, Jones K, Chakrabarti R, Iacobucci W. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2017 to 2032. Assoc Am Med Coll [Internet]. 2019;86.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Research Scientists

The number of biomedical scientists in the United States grew from 27,500 in 1990 to 69,000 in 2014. However, this growth varied dramatically by race and ethnicity. The percentage of Asians among biomedical scientists, for example, grew from 12 to 34 percent; while the percentage of Hispanics grew from 2 to 6 percent and the percentage of African American biomedical scientists only grew from 1 to 2 percent (369)Heggeness ML, Gunsalus KTW, Pacas J, McDowell G. The new face of US science. Nature [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 18];541:21–3.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Obtaining funding from the NIH, a milestone for promotion and tenure at many academic institutions where much of cancer health disparities research is performed, presents a further challenge. Minority applicants showed a persistent 7.5 percent lower funding rate compared with majority applicants from 2002 to 2016 (371)Nikaj S, Roychowdhury D, Lund PK, Matthews M, Pearson K. Examining trends in the diversity of the U.S. National Institutes of Health participating and funded workforce. FASEB J. 2018;32:6410–22.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Of note, funding rates for the NIH’s most commonly used grant program, the R01, remained lowest for African American applicants, irrespective of whether they had an MD or PhD degree, with probabilities for funding at 16.6 percent for African Americans, compared with 26.6 percent, 25.3 percent, and 28.7 percent for Asians, Hispanics, and whites, respectively (372)Ginther DK, Kahn S, Schaffer WT. Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 Research Awards: Is There Evidence of a Double Bind for Women of Color? Acad Med [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 18];91:1098–107.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

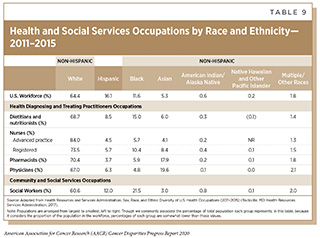

Physicians

Despite its importance, the diversity of the nation is not proportionately represented within the physician workforce. From 2011 to 2015, for example, the percentage of working age, non-Hispanic white physicians (67 percent) outpaced this group’s percentage of the overall U.S. workforce (64 percent) compared with Hispanic (6.3 percent) and African American (4.8 percent) physician representation (see Table 9). Practicing oncologists in 2016 had similar imbalances, with only 3 percent of these specialists identifying as Hispanic and an even smaller percentage—2.3 percent—identifying as African American (373)Winkfield KM, Flowers CR, Patel JD, Rodriguez G, Robinson P, Agarwal A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology strategic plan for increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the oncology workforce. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2576–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

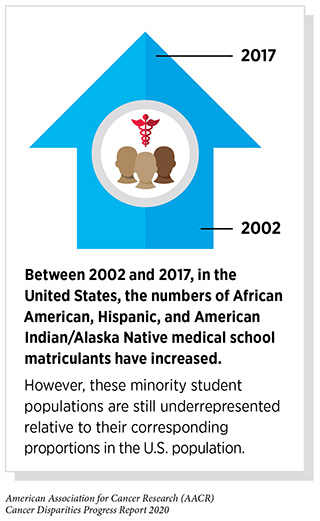

These imbalances in racial and ethnic diversity extend to the academic level, beginning at the level of residents and clinical fellows. African Americans and Hispanics make up only 6 percent and 8 percent, respectively, of all residents and fellows, and 4 percent and 5 percent of medical oncology fellows, while constituting 13 percent and 18 percent of the U.S. population (373)Winkfield KM, Flowers CR, Patel JD, Rodriguez G, Robinson P, Agarwal A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology strategic plan for increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the oncology workforce. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2576–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. At the assistant, associate, and full professor levels, African Americans and Hispanics were more underrepresented in 2016 than they were in 1990 relative to the proportions they constitute of the U.S. population (374)Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: A longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One [Internet]. Public Library of Science; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 18];13:e0207274.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Physician-scientists care for patients and conduct research. They have a special role to play in addressing cancer health disparities because the dual training provides a unique perspective on how to translate scientific knowledge into progress in health care and health policy. At present, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities comprise only 10 percent of matriculants in MD-PhD programs (375)2019 FACTS: Enrollment, Graduates, and MD-PhD Data | AAMC [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 18].[cited 2020 Jul 15].(376)Behera A, Tan J, Erickson H. Diversity and the next-generation physician-scientist. J Clin Transl Sci [Internet]. Cambridge University Press; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18];3:47–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Unfortunately, the opportunities for this dual training have lessened over time (377)Mukesh K. Jain, M.D., Vivian G. Cheung, M.D., Paul J. Utz, M.D., Brian K. Kobilka, M.D., Tadataka Yamada, M.D., and Robert Lefkowitz MD. Saving the Endangered Physician-Scientist — A Plan for Accelerating Medical Breakthroughs Mukesh. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:397–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(378)Carethers JM. Diversification in the medical sciences fuels growth of physician-scientists. J Clin Invest [Internet]. American Society for Clinical Investigation; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 23];129:5051–4.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Issues contributing to the declining number of physician-scientists include increasing student debt, child and family responsibilities, inflexible family leave policies, increasing time to become independent and funded researchers, insufficient protected time for research, and stagnant funding growth (368)Dall T, Reynolds R, Jones K, Chakrabarti R, Iacobucci W. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2017 to 2032. Assoc Am Med Coll [Internet]. 2019;86.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(373)Winkfield KM, Flowers CR, Patel JD, Rodriguez G, Robinson P, Agarwal A, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology strategic plan for increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the oncology workforce. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2576–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The lack of diversity in the physician-scientist workforce is also leading to a corresponding lack of diverse role models and mentors (374)Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: A longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One [Internet]. Public Library of Science; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 18];13:e0207274.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Other Health Care Professionals

The underrepresentation of minorities extends beyond research scientist and physician occupations. According to one survey, African Americans, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and Hispanics make up only 6.4 percent, 0.4 percent, and 5.3 percent, respectively, of registered nurses in the United States (379)Smiley RA, Lauer P, Bienemy C, Berg JG, Shireman E, Reneau KA, et al. The 2017 National Nursing Workforce Survey. J Nurs Regul [Internet]. Elsevier Masson SAS; 2018;9:S1–88.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Furthermore, underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities comprise only 9 percent of dentists who are often at the frontline of diagnosing oral cancers (380)Garcia RI, Blue Spruce G, Sinkford JC, Lopez MJ, Sullivan LW. Workforce diversity in dentistry – current status and future challenges. J Public Health Dent [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111); 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 18];77:99–104.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Urgent and immediate actions are necessary to strengthen diversity in the cancer workforce (see sidebar on Recommendations to Enhance Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the Cancer Workforce).

Achieving Health Equity through a Strong and Diverse Future Workforce

In this chapter we have described the biomedical research training pipeline and biomedical research and health care workforce, examined the current landscapes, and offered recommendations for attracting and engaging a diverse pool of students and trainees and building a broad, skilled, and diverse workforce for the biomedical sciences—essential steps to reduce the burden of cancer for an increasingly diverse America.

Enhancing diversity in training and the cancer workforce will expand the perspectives included and represented, fuel creativity, and make the training pipeline and workforce more reflective of our increasingly diverse nation and the populations bearing the unequal burden of cancer. Most importantly, enhancing diversity in cancer training and workforce is vital to effectively addressing cancer health disparities. Achieving a truly diverse and inclusive cancer research and care workforce is not only motivated by ethics and social justice, but also is essential to ensure top-quality scientific performance and cancer care. Succeeding in this endeavor requires dedicated commitment and concerted efforts from all stakeholders, including private and academic institutions, training institutions, federal agencies, industry entities, professional organizations, and individuals from all backgrounds.

Moving forward, it is critically important to provide more funding and create and support policies to ensure that we continue to advance training and workforce diversity in cancer. In addition, we must continue to evaluate whether these efforts are being effective in enhancing diversity in the biomedical and, in particular, the cancer workforce. Training and workforce diversity must remain a high priority if we are to realize the goal of eliminating cancer health disparities and, ultimately, achieving health equity.