Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors

In this section you will learn:

- In the United States, four out of 10 cancer cases and almost half of all cancer-related deaths are associated with preventable risk factors.

- Not using tobacco is the single best way a person can prevent cancer from developing.

- Nearly 20 percent of U.S. cancer diagnoses are related to excess body weight, alcohol intake, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

- About 3 percent of U.S. cancer diagnoses and deaths are related to infection with pathogens, including human papillomavirus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus, for which there are treatments to eliminate infection or vaccines to prevent infection.

- Exposure to many of the major cancer risk factors continues to be particularly high, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities and underserved populations.

- We need more effective strategies to disseminate our current knowledge of cancer prevention and implement evidence-based interventions to reduce the burden of cancer for everyone

Decades of basic, epidemiological, and clinical research have led to the identification of several factors, known as cancer risk factors, that increase a person’s chance of developing cancer (see Figure 2). Researchers estimate that more than 40 percent of the cancer cases diagnosed in the United States in 2014 and nearly half of all the cancer-related deaths in that year were caused by potentially avoidable cancer risk factors, including tobacco use, poor diet, alcohol intake, physical inactivity, obesity, infection with cancer-causing pathogens, and exposure to UV radiation (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. While epidemiological studies have shown associations between exposure to high levels of some of these risk factors (for example, smoking) and the risk of developing cancer, basic research has been critical in identifying the underlying mechanisms of cancer development as a result of these exposures. Studies among immigrant populations have been instrumental in showing how cancer incidence changes when populations move from one country to another, helping population scientists identify the risk factors most likely to be responsible for such changes. Together, these basic and population-based studies have allowed the classification of possible cancer-causing agents into different risk categories based on the level of evidence and the level of risk. These classifications guide cancer prevention strategies and policies to reduce the burden of cancer in the population.

The development and implementation of public education and policy initiatives designed to eliminate or reduce exposure to preventable causes of cancer have reduced cancer morbidity and mortality in the United States. For example, tobacco control efforts implemented since the 1960s have led to considerable reductions in smoking and smoking-related diseases, including lung cancer. Despite these measures, the prevalence of some of the major cancer risk factors continues to be high, particularly among segments of the U.S. population that experience cancer health disparities, such as racial and ethnic minorities, individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and those with lower educational attainment (see sidebar on Disparities in the Burden of Avoidable Cancer Risk Factors). Thus, we must identify more effective strategies to disseminate our current knowledge of cancer prevention and implement evidence-based interventions to reduce the burden of cancer for everyone.

Tobacco Use

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer and cancer-related deaths (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Tobacco use includes the use of cigarettes and other combustible tobacco products, such as cigars, as well as smokeless tobacco products (e.g., chewing tobacco and snuff), and pipe tobacco. It causes cancer because tobacco or secondhand smoke exposes individuals to many harmful chemicals that damage DNA, causing genetic and epigenetic alterations that lead to cancer development (137)CDC Vital Signs, November 2016. Cancer and tobacco use. CDC Vital Signs, November, 2016.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(138)Barrow TM, Klett H, Toth R, Böhm J, Gigic B, Habermann N, et al. Smoking is associated with hypermethylation of the APC 1A promoter in colorectal cancer: the ColoCare Study. J Pathol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Mar 15];243:366–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

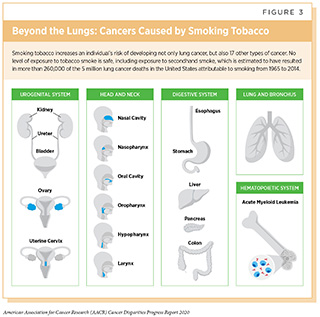

Smoking is linked to 17 different types of cancer in addition to lung cancer (see Figure 3). Moreover, even though not proven to cause prostate cancer, cigarette smoking is associated with a higher risk of death from prostate cancer, a higher risk of advanced-stage prostate cancer, and a higher risk of prostate cancer progression (139)United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress A Report of the Surgeon General. A Rep Surg Gen. 2014;1081.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Exposure to secondhand smoke also can cause lung cancer (140)Tsai J, Homa DM, Gentzke AS, Mahoney M, Sharapova SR, Sosnoff CS, et al. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Among Nonsmokers — United States, 1988–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2018;67:1342–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In cancer patients and survivors, cigarette smoking is associated with an increased risk of recurrence, poorer response to treatment, and increased treatment-related toxicity (139)United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress A Report of the Surgeon General. A Rep Surg Gen. 2014;1081.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Fortunately, cessation at any age can reduce the risk of cancer occurrence and cancer-related death (139)United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress A Report of the Surgeon General. A Rep Surg Gen. 2014;1081.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Thus, one of the most effective ways a person can lower his or her risk of developing cancer and lower his or her risk of other smoking-related conditions such as cardiovascular, metabolic, and lung diseases, is to avoid or eliminate tobacco use.

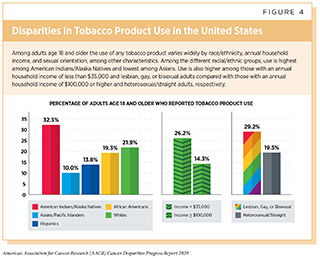

Use of tobacco in the United States differs widely by race/ethnicity (see Figure 4 and sidebar on Racial/Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence of Smoking).

Although African American adults smoke at comparable levels to non-Hispanic whites, tobacco-related morbidity and mortality rates are disproportionately higher among this population (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The reason for this is not fully understood and is likely to be multifactorial including differences in socioeconomic status impacting access to quality care, prevalence of additional risk factors such as obesity, exposure to secondhand smoke, and higher use of mentholated cigarettes. Of note, menthol smokers report increased nicotine dependence and reduced smoking cessation compared to non-menthol smokers (144)Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS, Gagosian SY, Abrams DB. Menthol cigarettes and the public health standard: a systematic review. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 23];17:983.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Several cancers that are linked to tobacco use, including stomach, liver, pancreatic, colorectal, and cervical cancer, have higher burdens in African Americans (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The continuing disparity in the overall cancer death rates between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites is driven by disparities in deaths from several cancers that are either caused by tobacco or are associated with worse disease among tobacco users and hence made more fatal by tobacco, specifically breast and colorectal cancer in women, and prostate, lung, and colorectal cancer in men (145)American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2019-2021. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2019. 2019;[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Quitting smoking can lower risk for cancer or death from cancer (139)United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress A Report of the Surgeon General. A Rep Surg Gen. 2014;1081.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Although African American adult cigarette smokers are more likely to report that they want to quit smoking and attempt to quit smoking as compared to smokers from other racial and ethnic groups, they are less successful at quitting than non-Hispanic white and Hispanic smokers (146)Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];65:1457–64.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This may be due to disparities in culturally tailored, evidence-based cessation strategies.

Policy interventions can reduce tobacco-related cancer disparities by helping people quit smoking, preventing people from starting to smoke, and reducing exposure to secondhand smoke. This can be done through comprehensive smoke-free laws, increasing taxes on tobacco products, reducing targeted advertising, and offering comprehensive and evidence-based cessation services (147)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices User Guide: Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control. 2015;1–52.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, certain policies enacted in the past have not provided as much benefit to racial and ethnic minorities as they have for whites. For instance, the uptake of smoke-free laws across the United States has reduced overall exposure to secondhand smoke. However, African Americans have benefited less than other groups from these laws and continue to have higher rates of exposure to secondhand smoke. Differences in smoking rates, implementation of smoke-free laws, and knowledge about the harms of secondhand smoke may contribute to these disparities (140)Tsai J, Homa DM, Gentzke AS, Mahoney M, Sharapova SR, Sosnoff CS, et al. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Among Nonsmokers — United States, 1988–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2018;67:1342–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Increasing cigarette prices, such as via tobacco tax increases, reduces tobacco use and prevents initiation of use (139)United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress A Report of the Surgeon General. A Rep Surg Gen. 2014;1081.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. and Hispanics and African Americans are more sensitive to tobacco prices than non-Hispanic whites. Tobacco companies have historically marketed their products more heavily to African Americans, particularly menthol cigarettes, and menthol cigarettes have in the past been exempt from stricter FDA regulations regarding flavored products (147)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices User Guide: Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control. 2015;1–52.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. African American adult cigarette smokers are less likely to report receiving physician advice to quit smoking or using prescription smoking cessation medication (148)Tibuakuu M, Okunrintemi V, Jirru E, Echouffo Tcheugui JB, Orimoloye OA, Mehta PK, et al. National Trends in Cessation Counseling, Prescription Medication Use, and Associated Costs Among US Adult Cigarette Smokers. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];2:e194585.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These data highlight the urgent need for all stakeholders to work together to develop and implement evidence-based population-level interventions to reduce the burden of tobacco use especially for racial and ethnic minorities.

The use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) has increased dramatically in the past ten years, and their long-term health impacts are unknown (149)Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL, Effects H, Delivery N, Health P, et al. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes [Internet]. National Academies Press; 2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Currently non-Hispanics have higher rates of awareness and use of e-cigarettes as compared to other racial and ethnic groups (132)Creamer MLR, Wang TW, Babb S, Cullen KA, Day H, Willis G, et al. Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults – United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Adolescent and young adult e-cigarette users are two to four times more likely to begin using conventional tobacco products (149)Stratton K, Kwan LY, Eaton DL, Effects H, Delivery N, Health P, et al. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes [Internet]. National Academies Press; 2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Continuing research on the health effects of e-cigarettes and their use across different population groups is necessary to ensure that use of these devices does not increase existing disparities, and that potential benefits (if any) for cessation purposes are distributed equally across groups.

Obesity

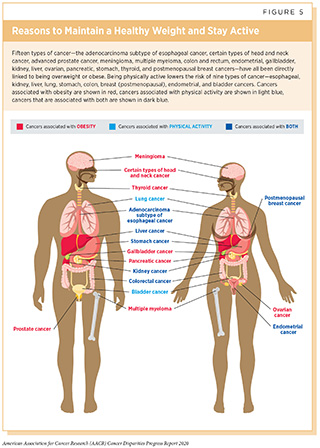

In the United States, excess body weight is associated with nearly 5 percent of all cancers in men and 11 percent of all cancers in women (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Being overweight or obese as an adult increases a person(151)Body fatness and weight gain and the risk of cancer. World Cancer Res Fund/American Inst Cancer Res Contin Updat Proj Expert Rep 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 15].’s risk for developing 15 types of cancer (see Figure 5) (150)Lauby‑secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body Fatness and Cancer — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. 2016;8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. There is evidence that obesity at the time of diagnosis is linked to increased risk of death from early-stage breast, colorectal, endometrial, and prostate cancer (150)Lauby‑secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif K. Body Fatness and Cancer — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. 2016;8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(152)Cao Y, Ma J. Body Mass Index, Prostate Cancer-Specific Mortality, and Biochemical Recurrence: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 16];4:486–501.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(153)Campbell PT, Newton CC, Dehal AN, Jacobs EJ, Patel A V., Gapstur SM. Impact of Body Mass Index on Survival After Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis: The Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 16];30:42–52.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

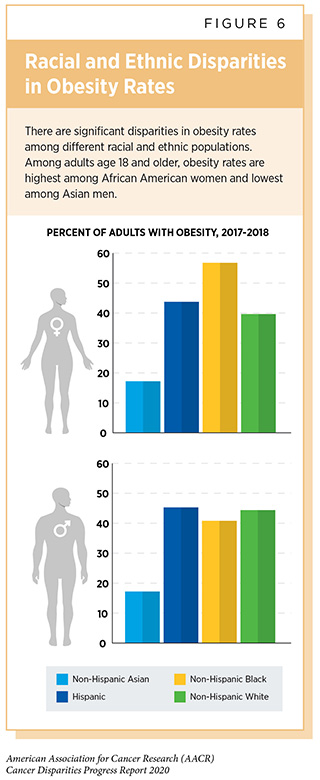

There are significant disparities in obesity rates among different racial and ethnic populations (see sidebar on Disparities in Obesity Rates in the United States and Figure 6) and several of the cancers that have higher burden among racial and ethnic minorities are associated with obesity (see sidebar on Disparities in the Burden of Obesity-related Cancers).

Focusing on obesity in childhood is key to reducing disparities in obesity and cancer because risk of adult obesity is greater among individuals who were obese as children, and overweight African American youth are more likely to become obese adults compared to non-Hispanic white obese youth (155)Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Racial Differences in the Tracking of Childhood BMI to Adulthood. Obes Res [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2019 Dec 16];13:928–35.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Notably, the association between obesity and cancer risk may vary among racial and ethnic groups. For example, a stronger association between obesity and risk of prostate cancer is seen among African American men compared with non-Hispanic white men (156)Barrington WE, Schenk JM, Etzioni R, Arnold KB, Neuhouser ML, Thompson IM, et al. Difference in Association of Obesity With Prostate Cancer Risk Between US African American and Non-Hispanic White Men in the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 16];1:342.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Although the increased cancer risk associated with excess body weight and weight gain is clear, the exact mechanisms underpinning this variation in risk are not fully understood. Further research to understand these mechanisms will lead to interventions and policies that can effectively reduce cancer risks and cancer health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities.

Dietary Factors

In the United States, nearly 5 percent of all cancer cases and deaths among adults age 30 and older are attributable to eating a poor diet (157)Zhang FF, Cudhea F, Shan Z, Michaud DS, Imamura F, Eom H, et al. Preventable Cancer Burden Associated with Poor Diet in the United States. JNCI Cancer Spectr [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Low intake of healthy foods such as whole grains, fruits, nuts, and seeds combined with the high intake of unhealthy foods such as sugar-sweetened drinks and high levels of red and processed meats are, in fact, responsible for one in five deaths globally (158)Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet [Internet]. 2019;6736.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

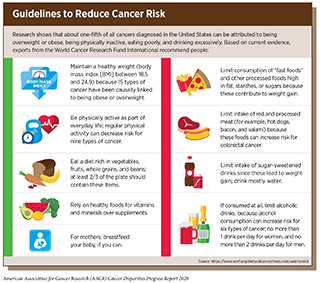

The role that dietary factors play in determining cancer risk is greater for some types of cancers than it is for others. For example, it is estimated that more than 8 percent of colorectal cancer cases are caused by high intake of processed meats, and nearly 18 percent of oral/pharyngeal cancers are due to low consumption of fruits and vegetables (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Intensive efforts from all stakeholders are needed if we are to increase the number of people who consume a balanced diet and maintain a healthy lifestyle to minimize the risk of cancer development (see sidebar on Guidelines to Reduce Cancer Risk).

Studies across the United States have shown that overall, Hispanics have better quality diets than African Americans, and of comparable quality to non-Hispanic whites; whereas African Americans have lower quality diets than whites, in particular for total vegetable and grain intake (159)Wang Y, Chen X. How much of racial/ethnic disparities in dietary intakes, exercise, and weight status can be explained by nutrition- and health-related psychosocial factors and socioeconomic status among US adults? J Am Diet Assoc [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 16];111:1904–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(160)Hiza HAB, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Diet [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 16];113:297–306.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among African Americans, the strongest barriers to consuming a high-quality diet are lack of time to prepare healthy food, the cost of healthy food, and the convenience of fast foods (161)Richards Adams IK, Figueroa W, Hatsu I, Odei JB, Sotos-Prieto M, Leson S, et al. An Examination of Demographic and Psychosocial Factors, Barriers to Healthy Eating, and Diet Quality Among African American Adults. Nutrients [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];11:519.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among Hispanics, dietary quality has been observed to vary considerably by country of origin; therefore, interventions tailored to Hispanics should consider these differences (162)Siega-Riz AM, Pace ND, Butera NM, Van Horn L, Daviglus ML, Harnack L, et al. How Well Do U.S. Hispanics Adhere to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans? Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Heal equity [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];3:319–27.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For white and African American young adults (ages 18-39) in the U.S., diet quality has improved over the past two decades, while remaining the same for Mexican Americans. Notably, even though individuals from all income levels experienced an improvement in diet quality, the disparity between low- and high-income groups increased considerably (163)Patetta MA, Pedraza LS, Popkin BM. Improvements in the nutritional quality of US young adults based on food sources and socioeconomic status between 1989-1991 and 2011-2014. Nutr J [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];18:32.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Overall, in the United States, diet quality improves with increased income level (160)Hiza HAB, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Diet [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 16];113:297–306.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., which may contribute to cancer health disparities.

Sugar-sweetened beverages are a major contributor to obesity and excess body weight among U.S. youth and adults (165)Rosiner A, Herrick K, Gahche JJ, Park S. Sugar-sweetened Beverage Consumption Among U.S. Youth, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief [Internet]. 2017;1–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(166)Rosiner A, Herrick K, Gahche JJ, Park S, Kumar G, Pan L, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adults-18 States, 2012. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2014;63:686–90.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Reports indicate persistent disparities in the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages across racial and ethnic populations, with African American, Mexican American, and other Hispanic adults and children being more likely to drink sugar-sweetened beverages than their white counterparts (167)America HF. Introduction HEALTHY FOOD AMERICA | Report Sugary Drinks in America: Who’s Drinking What and How Much? 2018;1–23.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. A recent policy approach aimed at reducing obesity is the introduction of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages in several local jurisdictions in the United States (168)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2017-2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. It is encouraging that there is already some indication there has been a reduction in consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages since the implementation of these taxes, especially in lower-income, racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods (169)Lee MM, Falbe J, Schillinger D, Basu S, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption 3 Years After the Berkeley, California, Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:637–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(170)Roberto CA, Lawman HG, Levasseur MT, Mitra N, Peterhans A, Herring B, et al. Association of a Beverage Tax on Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages with Changes in Beverage Prices and Sales at Chain Retailers in a Large Urban Setting. JAMA – J Am Med Assoc. 2019;321:1799–810.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, ongoing research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of these policies on obesity and obesity-related health outcomes such as cancer.

The burden of many diet-related diseases, including cancer, is disparately higher in low-income and racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods (171)Christopher GC, Harris CM, Harris RT, Gibson SM, Mcguire CK, Sanchez E, et al. The State of Obesity 2017. Trust Am Heal [Internet]. 2017;[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These neighborhoods are also often located in “food deserts,” lacking access to healthy food retail such as supermarkets, while having an overabundance of convenience stores with unhealthy and fast food options. However, even when comparing communities with similar levels of poverty, studies show that African American and Hispanic neighborhoods have fewer supermarkets and more convenience stores than white neighborhoods (172)Bower KM, Thorpe RJ, Rohde C, Gaskin DJ. No Title. 2014 [cited 2019 Oct 16];58.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These findings underscore the need for evidence-based health improvement strategies to increase access to affordable and nutritious food for racial and ethnic minority populations.

For cancer survivors, the current recommendation is to follow the same guidelines for cancer prevention (see sidebar on Guidelines to Reduce Cancer Risk). However, disparities have been reported showing that African American survivors are less likely to adhere to dietary recommendations compared with non-Hispanic white survivors (173)Byrd DA, Agurs-Collins T, Berrigan D, Lee R, Thompson FE. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Dietary Intake, Physical Activity, and Body Mass Index (BMI) Among Cancer Survivors: 2005 and 2010 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS). J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Mar 6];4:1138–46.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., and that being younger, less educated, having lower income, and higher body mass index are all determinants of low adherence to dietary recommendations (174)Springfield S, Odoms-Young A, Tussing-Humphreys L, Freels S, Stolley M. Adherence to American Cancer Society and American Institute of Cancer Research dietary guidelines in overweight African American breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 16];13:257–68.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(175)Kane K, Ilic S, Paden H, Lustberg M, Grenade C, Bhatt A, et al. An Evaluation of Factors Predicting Diet Quality among Cancer Patients. Nutrients [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 16];10:1019.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These data emphasize the need for the implementation of evidence-based population-level interventions that can mitigate such disparities to improve outcomes for African American cancer patients and survivors.

Physical Activity

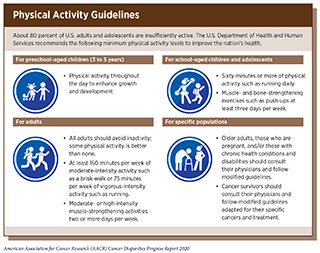

An estimated 3 percent of all cancers, with up to 16 percent of colorectal cancers and 4 percent of breast cancers in the United States, can be attributed to lack of physical activity (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Physical activity, which is any activity that involves our muscles and is different from resting, is known to have direct effects on the body, such as the immune system, hormones, and metabolism, which may affect our risk of cancer development. According to a recent report, physical activity can definitely reduce the risk of developing eight types of cancer (176)World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Physical activity and the risk of cancer. [cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Figure 5). There is growing evidence that physical fitness may also reduce the risk of developing additional types of cancer (177)Marshall CH, Al‐Mallah MH, Dardari Z, Brawner CA, Lamerato LE, Keteyian SJ, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and incident lung and colorectal cancer in men and women: Results from the Henry Ford Exercise Testing (FIT) cohort. Cancer [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 19];cncr.32085.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(178)Matthews CE, Moore SC, Arem H, Cook MB, Trabert B, Håkansson N, et al. Amount and Intensity of Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Lower Cancer Risk. J Clin Oncol. 2019;JCO.19.02407.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Furthermore, physical activity can dramatically lower rates of all causes of death after a diagnosis of certain types of cancer (179)MCTIERNAN A, FRIEDENREICH CM, KATZMARZYK PT, POWELL KE, MACKO R, BUCHNER D, et al. Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival. Med Sci Sport Exerc [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 20];51:1252–61.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Considering the above evidence, it is concerning that four out of 10 U.S. adults are physically inactive and only a quarter of children and teenagers get the recommended hour of moderate-to-vigorous exercise a day (180)Ussery EN, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, Katzmarzyk PT, Carlson SA. Joint Prevalence of Sitting Time and Leisure-Time Physical Activity Among US Adults, 2015-2016. JAMA [Internet]. American Medical Association; 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 19];320:2036.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(181)National Physical Activity Plan Alliance. The 2018 United States Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. Washington, DC: National Physical Activity Plan Alliance, 2018. 2001;8:33–42.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(182)Du Y, Liu B, Sun Y, Snetselaar LG, Wallace RB, Bao W. Trends in Adherence to the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans for Aerobic Activity and Time Spent on Sedentary Behavior Among US Adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2019;2:e197597.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Racial and ethnic disparities have been reported in the proportion of individuals who are physically inactive, with Hispanics and African Americans having a higher prevalence of physical inactivity compared to whites, and these differences are not explained by socioeconomic status (133)Goding Sauer A, Siegel RL, Jemal A, Fedewa SA. Current Prevalence of Major Cancer Risk Factors and Screening Test Use in the United States: Disparities by Education and Race/Ethnicity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019;28:629–42.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(136)Adult Physical Inactivity Prevalence Maps by Race/Ethnicity | Physical Activity | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 17].[cited 2020 Jul 15].(183)Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE, Carter-Pokras O, Ainsworth BE. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Prev Med [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2019 Dec 16];18:46–53.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Similar trends have been observed across the United States for various types of physical activity, with whites having a greater proportion of individuals who are physically active compared with African Americans and Hispanics (184)CDC WONDER DATA2010 – Home Page [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 16].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Living in low-income neighborhoods, where there is a lack of safe and affordable options for physical exercise, such as gyms, bike trails, and walking paths, contributes to disparities in the burden of obesity-related diseases in racial and ethnic minorities. Therefore, it is imperative that health care professionals and policy makers work together to increase awareness of the benefits of physical activity and support efforts to implement programs and policies to facilitate physical activity for all Americans (see sidebar on Physical Activity Guidelines).

UV Exposure

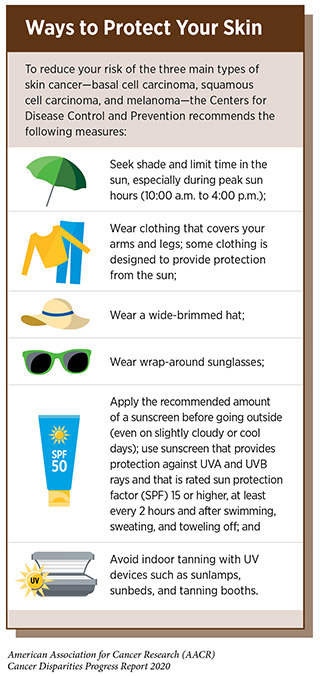

Exposure to UV radiation from the sun or indoor tanning devices can cause genetic mutations and poses a serious threat for the development of all three main types of skin cancer—basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma, which is the deadliest form of skin cancer. Thus, one of the most effective ways a person can reduce his or her risk of skin cancer is by practicing sun-safe habits and not using UV indoor tanning devices (see sidebar on Ways to Protect Your Skin).

Overall, UV light accounts for 4-6 percent of all cancers, and is responsible for 95 percent of skin melanomas (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Disparities have been reported in the level of knowledge about the danger of sun exposure and importance of using sunscreen, with African Americans and Hispanics having less knowledge and being less likely to use sunscreen than whites (186)Cheng CE, Irwin B, Mauriello D, Hemminger L, Pappert A, Kimball AB. Health Disparities Among Different Ethnic and Racial Middle and High School Students in Sun Exposure Beliefs and Knowledge. J Adolesc Heal [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2019 Dec 16];47:106–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(187)Summers P, Bena J, Arrigain S, Alexis AF, Cooper K, Bordeaux JS. Sunscreen use: Non-Hispanic Blacks compared with other racial and/or ethnic groups. Arch Dermatol [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 16];147:863–4.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. According to a recent report, only 6 percent of African American and 24 percent of Hispanic fifth graders reported using sunscreens compared with 45 percent of their non-Hispanic white counterparts (188)Correnti CM, Klein DJ, Elliott MN, Veledar E, Saraiya M, Chien AT, et al. Racial disparities in fifth-grade sun protection: Evidence from the Healthy Passages study. Pediatr Dermatol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 7];35:588–96.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These data are concerning given the fact that sunburns, a clear indication of overexposure to UV radiation, occurring in childhood pose one of the greatest risks for developing skin cancer later in life (189)Dennis LK, Vanbeek MJ, Beane Freeman LE, Smith BJ, Dawson D V, Coughlin JA. Sunburns and risk of cutaneous melanoma: does age matter? A comprehensive meta-analysis. Ann Epidemiol [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2008 [cited 2019 Jul 10];18:614–27.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The level of knowledge about skin cancer risks among African Americans and Hispanics is influenced by level of education (190)Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, Elmets C. Skin cancer risk perceptions: a comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. J Am Acad Dermatol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 16];66:771–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Overall, the disparity in skin cancer prevention among these two minority groups is of public health relevance and is reflected in the fact that even though African Americans and Hispanics have lower incidence of skin cancer, they tend to be diagnosed at more advanced stages. Continued efforts from all sectors are necessary to identify and implement more effective interventions to promote sun-safe behavior among racial and ethnic minorities and to reduce the burden of skin cancers for these population groups.

Infectious Agents

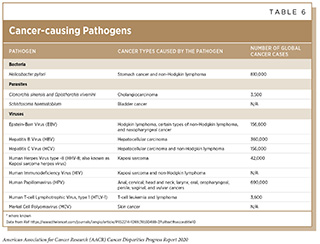

Persistent infection with several pathogens including HPV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and H. pylori are known to cause cancer (see Table 6). In the United States, in 2014, about 3 percent of all cancer cases and cancer deaths were attributable to infection with pathogens (57)Islami F, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2017;68:31–54.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Individuals, therefore, can significantly lower their risks by protecting themselves from infection with these pathogens or by obtaining treatment, if available, to eliminate an infection (see sidebar on Preventing or Eliminating Infection with the Four Main Cancer-causing Pathogens).

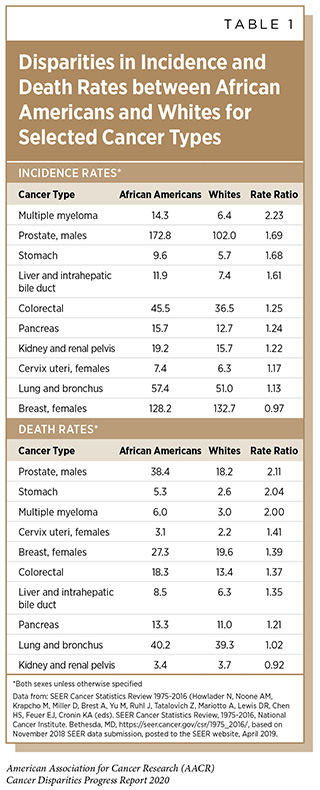

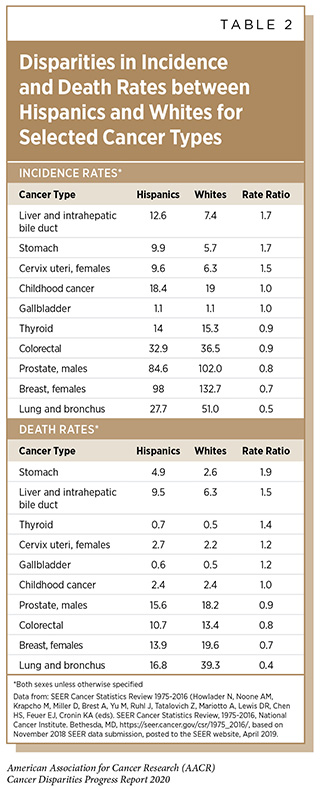

Although there are strategies available to eliminate, treat, or prevent infection with H. pylori, HBV, HCV, and HPV that can significantly lower an individual’s risks for developing an infection-related cancer, it is important to note that these strategies are not effective at treating infection-related cancers once they develop. It is also clear that these strategies are not being used optimally. For example, even though the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), an independent, volunteer panel of experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, recommends one-time HCV testing for baby boomers, recent data show that only 14 percent of adults in this population group have been tested (193)Kasting ML, Giuliano AR, Reich RR, Roetzheim RG, Duong LM, Thomas E, et al. Hepatitis C virus screening trends: A 2016 update of the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol [Internet]. Elsevier; 2019 [cited 2019 May 14];60:112–20.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Furthermore, even though HBV vaccination has been available for decades, disparities in access to vaccines remain for African Americans and Hispanics (194)Forde KA. Ethnic Disparities in Chronic Hepatitis B Infection: African Americans and Hispanic Americans. Curr Hepatol Reports [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];16:105–12.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This in turn contributes to the higher rates of liver cancer that occur in these racial and ethnic populations (see Table 1 and Table 2, respectively).

Given that in the United States, liver cancer incidence is increasing rapidly and that infection with HBV or HCV accounts for 65 percent of liver cancers, more effective implementation of vaccination, screening, and treatment is needed urgently to significantly reduce the burden of this disease (195)Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Altekruse SF, Ward JW, Jemal A, Sherman RL, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2012, featuring the increasing incidence of liver cancer. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016 [cited 2019 Jun 19];122:1312–37.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Notably, liver cancer incidence and mortality rates are higher among American Indian and Alaska Natives compared to whites (195)Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Altekruse SF, Ward JW, Jemal A, Sherman RL, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2012, featuring the increasing incidence of liver cancer. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016 [cited 2019 Jun 19];122:1312–37.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 19];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among American Indian and Alaska Natives, HCV infections occur earlier than in the general population and HCV-related deaths are double the national rate (196). In this regard, a recent initiative that aims to reduce the burden of HCV infection is the recommendation from the Indian Health Service for universal screening of all American Indian and Alaska Native adults (https://www.ihs.gov/ihm/sgm/).

H. pylori is a type of bacterium that has been shown to cause gastric cancer. Among U.S. adults, a higher prevalence of infection has been reported in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic blacks compared with non-Hispanic whites (15)Grad YH, Lipsitch M, Aiello AE. Secular Trends in Helicobacter pylori Seroprevalence in Adults in the United States: Evidence for Sustained Race/Ethnic Disparities. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 11];175:54–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., which may contribute to the higher rates of gastric cancer in these populations. Declining rates of H. pylori infection have been reported recently, which may be due in part to improve access to antibiotics, increased use of refrigeration, and decreased use of salted foods (197)Luo G, Zhang Y, Guo P, Wang L, Huang Y, Li K. Global patterns and trends in stomach cancer incidence: Age, period and birth cohort analysis. Int J Cancer [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 17];141:1333–44.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

HPV is a known cause of many cancers as it can infect both the genitals and the oral cavity. It is estimated that in the United States, HPV infection accounts for nearly 34,000 cancer cases each year including almost all cervical and anal cancers as well as the majority of vaginal, vulvar, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers (198)HPV Vaccination for Cancer Prevention: Progress, Opportunities, and a Renewed Call to Action. A Report to the President of the United States from the Chair of the President’s Cancer Panel. Bethesda (MD): President’s Cancer Panel; 2018 Nov. 1971;281.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. HPV vaccines are highly effective, and it has been estimated that if used as recommended that they could prevent up to 90 percent of HPV-related cancers. Cervical cancer, moreover, can be detected at its very early stages, allowing treatment to eradicate early lesions and prevent the cancer from developing altogether, as discussed in Disparities in Cancer Screening.

In the United States, the prevalence of genital HPV infection and of any oral HPV infection is higher among African American adults age 18 to 59 compared with their Hispanic and non-Hispanic white counterparts (199)Mcquillan G, Kruszon-moran D, Markowitz LE, Unger ER, Paulose-ram R. Prevalence of HPV in Adults Aged 18 – 69 : United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief [Internet]. 2017;2011–4.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Consequently, there are significant disparities in the burden of HPV-associated cancers in racial and ethnic minorities. For instance, even though overall cervical cancer rates have decreased in the United States, African American and Hispanic women still have higher rates of HPV-associated cervical cancer compared with women of other races and non-Hispanic women respectively (200)Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, Thomas CC, Markowitz LE, Benard VB. Trends in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers — United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2018;67:918–24.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Currently, the coverage for HPV vaccination ranges widely across the United States, with only about 50 percent of adolescents ages 13 to 17 up to date with the recommended regimen (32)Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:718–23.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Unfortunately, disparities exist by race and ethnicity, with African American girls ages 13 to 17 being less likely than their white counterparts to have completed the recommended dose (201)Hirth J. Disparities in HPV vaccination rates and HPV prevalence in the United States: a review of the literature. Hum Vaccin Immunother [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];15:146–55.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This disparity does not seem to be explained by sociodemographic and health care access, suggesting as yet unidentified additional barriers that need to be addressed (202)Gelman A, Miller E, Schwarz EB, Akers AY, Jeong K, Borrero S. Racial disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination: does access matter? J Adolesc Health [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 17];53:756–62.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Therefore, there is a great need for programs designed to increase prevention, like screening and vaccination, and reduce barriers in a culturally sensitive manner, in order to reduce cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates.

Social and Behavioral Stressors

Stress-related social and behavioral factors have been considered as possible cancer risk factors. For example, it has been found that having a stress-prone personality and/or poor coping skills, as well as emotional distress, can affect incidence, mortality, and survival for various types of cancer (60)Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 16];5:466–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. and that having stressful life experiences can affect survival from multiple types of cancer. It is not clear if the effects of stress-related psychological factors on cancer are due to an increase in cancer risk behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, poor diet, and physical inactivity, or due to direct effects on our bodies. For example, stress can directly affect hormones and/or cellular processes, which in turn may contribute to cancer formation (60)Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat Clin Pract Oncol [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 16];5:466–75.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(203)Vick AD, Burris HH. Epigenetics and Health Disparities. Curr Epidemiol reports [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 17];4:31–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One area of intensive research investigation is understanding the contribution of the allostatic load, which describes the combined influences of stresses, lifestyle, and environmental exposures, on the lifetime risk of various diseases such as cancer (204)Xing CY, Doose M, Qin B, Lin Y, Plascak JJ, Omene C, et al. Prediagnostic Allostatic Load as a Predictor of Poorly Differentiated and Larger Sized Breast Cancers among Black Women in the Women’s Circle of Health Follow-Up Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 22];29:216–24.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(205)Shiels PG, Buchanan S, Selman C, Stenvinkel P. Allostatic load and ageing: linking the microbiome and nutrition with age-related health. Biochem Soc Trans [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 22];47:1165–72.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Among the various risk factors that may induce stress are social isolation, which has been shown to contribute to increased morbidity and mortality, particularly among minorities (206)Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect Biol Med [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2019 Dec 17];46:S39-52.[cited 2020 Jul 15].; and racial discrimination, even perceived discrimination, which can contribute to poor physical and mental health among minorities (207)Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2019 Dec 17];116:404–16.[cited 2020 Jul 15]., and has been linked to breast cancer among African American women (208)McClintock MK, Conzen SD, Gehlert S, Masi C, Olopade F. Mammary Cancer and Social Interactions: Identifying Multiple Environments That Regulate Gene Expression Throughout the Life Span. Journals Gerontol Ser B [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2019 Dec 17];60:32–41.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Moreover, gentrification, segregation, and discrimination have been linked to stage at breast cancer diagnosis, cancer-specific mortality, and breast cancer incidence (66)Linnenbringer E, Gehlert S, Geronimus AT. Black-White Disparities in Breast Cancer Subtype: The Intersection of Socially Patterned Stress and Genetic Expression. AIMS public Heal [Internet]. AIMS Press; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 16];4:526–56.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Various studies have proposed that psychological and social factors may also contribute to the observed disparities for prostate cancer among African American men (209)Cuevas AG, Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Cofie L, Zaitsu M, Allen J, Williams DR. Placing prostate cancer disparities within a psychosocial context: challenges and opportunities for future research. Cancer Causes Control [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:443–56.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. It is therefore imperative that additional studies on different cancers, populations, and settings are undertaken in order to fully elucidate the role of psychosocial factors on cancer risk, and that appropriate interventions are deployed in order to prevent these factors and minimize their contribution to cancer health disparities.

Other Cancer-causing Factors

There are several other preventable cancer-causing factors with disparate burden among racial and ethnic minorities. For example, involuntary exposures to environmental pollutants usually occur in subgroups of the population, such as workers in certain industries who may be exposed to carcinogens on the job or individuals living in low-income neighborhoods. Similarly, there are disparities in the burden of cancers caused by environmental exposures based on geographic locations and socioeconomic status.

Outdoor Air Pollution

Outdoor air pollution has been found to be a cancer-causing agent, primarily for lung cancer, but possibly other cancers too. It is estimated that about 3 to 5 percent of lung cancer cases are due to outdoor pollution (210)Loomis D, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, et al. The carcinogenicity of outdoor air pollution. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Jun 19];14:1262–3.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Importantly, African Americans and Hispanics have been reported to be exposed to higher levels of outdoor air pollution than non-Hispanic whites (211)Tessum CW, Apte JS, Goodkind AL, Muller NZ, Mullins KA, Paolella DA, et al. Inequity in consumption of goods and services adds to racial-ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];116:6001–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. A study in California that integrated measures of air pollution as well as other environmental hazards concluded that African Americans and Hispanics were more likely than whites to live in proximity to multiple environmental health hazards (212)Cushing L, Faust J, August LM, Cendak R, Wieland W, Alexeeff G. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cumulative Environmental Health Impacts in California: Evidence From a Statewide Environmental Justice Screening Tool (CalEnviroScreen 1.1). Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];105:2341–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Pesticides and Endocrine-disrupting Chemicals

There are many chemical compounds that are used in agriculture, in the house, and in some occupations, to combat various pests, including weeds, and to protect us from fires, such as fire-retardant chemicals. It is a diverse group of chemicals, so each type needs to be studied separately. Several pesticides have been linked with cancer development, including lung, pancreatic, colorectal, prostate, brain, leukemia, and bladder cancer, as well as non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma (213)Weichenthal S, Moase C, Chan P. A review of pesticide exposure and cancer incidence in the Agricultural Health Study cohort. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2019 Dec 17];118:1117–25.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(214)Alavanja MCR, Bonner MR. Occupational pesticide exposures and cancer risk: a review. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 17];15:238–63.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Pesticides and other products can disrupt the function of hormones, which are produced by a body’s endocrine system, and some of these endocrine-disrupting chemicals have been linked to cancer (215)Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon J-P, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:293–342.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. It has been estimated that African Americans and Mexican Americans suffer a higher burden of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals than other racial and ethnic groups, primarily because of higher exposure to persistent pesticides and flame retardants among these two minority groups (216)Attina TM, Malits J, Naidu M, Trasande L. Racial/ethnic disparities in disease burden and costs related to exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the United States: an exploratory analysis. J Clin Epidemiol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];108:34–43.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Night Shift Work

There is accumulating scientific evidence that qualitative and quantitative sleep disturbances increase a person’s risk for developing cancer. Notably, working at night or working in airplanes that cross many time zones can lead to the disruption of the regular circadian cycle and have possible implications in cancer formation, mainly for breast, prostate, colon, and rectal cancers (217)IARC Monographs Vol 124 group EM, Germolec D, Kogevinas M, McCormick D, Vermeulen R, Anisimov VN, et al. Carcinogenicity of night shift work. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];20:1058–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Research into the role of circadian rhythms in disease including cancer is an active area of investigation. Both African Americans and Hispanics have been found to have higher prevalence of short sleep duration, including night shift work, compared with whites (218)Jackson CL, Redline S, Kawachi I, Williams MA, Hu FB. Racial disparities in short sleep duration by occupation and industry. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 17];178:1442–51.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(219)Grandner MA, Williams NJ, Knutson KL, Roberts D, Jean-Louis G. Sleep disparity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Sleep Med [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];18:7–18.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, more work is needed to completely understand the causes and develop potential interventions for this underappreciated cancer risk factor as well as to identify its role in cancer health disparities.

As we learn more about the various environmental, occupational, and other cancer risk factors and identify those segments of the U.S. population who are exposed to these factors, we need to develop and implement new and/or more effective policies and health care interventions that benefit everyone, including the most vulnerable and underserved populations.