Disparities in Clinical Research and Cancer Treatment

In this section, you will learn:

- Clinical trials establish whether new treatments are safe and effective; lack of sociodemographic diversity among clinical trial participants represents a major barrier to advancing cancer care for all patient populations.

- Improved diversity among clinical trial participants requires health care providers to equitably offer clinical trial options to all patients regardless of race, ethnicity, geography, or other sociodemographic factors such as health insurance.

- Improved diversity among clinical trial participants requires attention to trial design regarding accrual sites and outreach; involvement of a diverse workforce and patient navigators; use of culturally tailored patient education; and minimizing the costs associated with trial participation.

- Despite many advances in cancer treatment, patients from racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations are less likely to receive the recommended standard of care for their cancer.

- Recent studies have shown that racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes for several types of cancer can be eliminated if every patient has equitable access to guideline-adherent treatments.

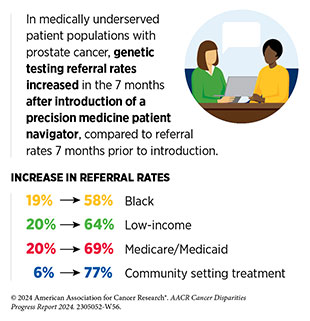

- Patient navigation and community engagement can reduce disparities in cancer treatment among underserved groups and potentially improve outcomes for all patients with cancer.

Progress across the continuum of cancer research and patient care improves survival and quality of life for people in the United States and around the world. In the United States, the annual decline in the overall cancer death rate has accelerated over the past two decades (1)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2023. Accessed: Feb 29, 2024. . This progress is driven by the dedicated efforts of individuals working throughout the cycle of medical research (see Sidebar 24).

Clinical Research

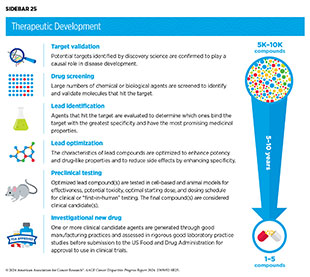

The rapid pace of progress against cancer is attributable in part to the new and effective treatments that are available today, thanks to the discoveries made through decades of research in basic and translational sciences. These discoveries have deepened our understanding of the cellular and molecular underpinnings of cancer initiation and progression and have led to the identification of a range of molecular targets that drive cancer (see Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Disparities). After a potential therapeutic target is identified, it takes many more years of preclinical research before a candidate therapeutic is developed and ready for testing in clinical research, also known as clinical studies or clinical trials (see Sidebar 25).

Clinical trials evaluate the safety and efficacy of candidate agents before a preventive intervention or therapeutic can be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and used as part of patient care. All clinical trials are critically reviewed and approved by institutional review boards before they can begin and are monitored throughout their duration. Patient safety and understanding of the clinical trial are prioritized through the informed consent process, which involves a discussion between the clinical research team and the patient about the trial’s purpose and what is expected of the patient, potential benefits and risks, alternative treatments, and the patient’s right to withdraw at any time without consequences.

There are many benefits to participating in a clinical trial, as highlighted in the personal experience of Anibal Torres. These include access to potentially more effective treatments before they are widely available, a direct contribution to lifesaving cancer research, and an active involvement in making health care decisions (567)Abu Rous F, et al. (2024) JAMA Oncol, 10: 416. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, there is evidence that clinical trial participants often have improved outcomes compared to nonparticipants (568)Duenas JAC, et al. (2023) BMC Cancer, 23: 786. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](569)Koo KC, et al. (2018) BMC Cancer, 18: 468. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are several types of cancer clinical trials, including prevention trials, screening trials, treatment trials, and supportive or palliative care trials, each designed to answer different research questions (see Sidebar 26). Clinical studies in which participants are randomly assigned to receive experimental treatment or standard-of-care treatment are called randomized clinical trials and are considered the most rigorous.

Clinical trials that test candidate therapeutics for patients with cancer have traditionally been done in three successive phases (see Figure 12). Observations made during the real-world use of a drug after it is approved by FDA can also be utilized to further enhance the use of that drug. The multiphase clinical testing process is extremely costly, requires many patients, and takes years to complete (570)Arfe A, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 917. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](571)Shadbolt C, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2250996. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Identifying and implementing more efficient clinical development strategies are areas of extensive investigation for all members of the medical research community.

Disparities in Cancer Clinical Trial Participation

While researchers are continually identifying and implementing new ways of designing, reviewing, and conducting clinical trials that are yielding advances in patient care, there are still numerous opportunities for improvements. Two of the most pressing shortcomings that need to be addressed urgently are low participation in cancer clinical trials and a lack of sociodemographic diversity among those who do participate (see Sidebar 27) (574)Unger JM (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2322436. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](576)Loehrer AP, et al. (2024) Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, 38: 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Low participation in clinical trials means that many trials fail to enroll enough participants to draw meaningful conclusions about the effectiveness of the anticancer therapeutic being tested. Lack of diversity in clinical studies means that the trial participant population is not reflective of the real-world demographics of the cancer burden—the population that is likely to receive the treatments if and when they are approved (577)In: Bibbins-Domingo K, Helman A, editors. Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups. Washington (DC)2022. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Underrepresentation in clinical research compromises the generalizability of the research findings to the entire US patient population.

It is well established that many segments of the US population, such as racial and ethnic minority populations, sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations, individuals living in rural and poorer areas, adolescents and young adults, people with disabilities, and older adults are underrepresented in cancer clinical trials (584)Saez-Ibanez AR, et al. (2022) Nat Rev Drug Discov, 21: 870. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](586)Riaz IB, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 180. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](587)Earl ER, et al. (2023) Neurooncol Pract, 10: 472. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](588)DeCormier Plosky W, et al. (2022) Health Aff (Millwood), 41: 1423. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](589)Zhao S, et al. (2024) BMC Cancer, 24: 30. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](590)Kanapuru B, et al. (2022) Blood Adv, 6: 1684. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](591)Rosser BRS, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 5093. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](592)Donzo MW, et al. (2024) Cancer Med, 13. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](593)Roth M, et al. (2021) Cancer Med, 10: 7620. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Despite the enactment of the landmark NIH Revitalization Act by the US Congress in 1993 to improve representation of women and minority populations in clinical trials and numerous initiatives from FDA and NCI since then, lack of diversity as well as underreporting of race, ethnicity, and age of participants continues to be an ongoing challenge (see Policies to Address Disparities in Clinical Research and Care). In fact, several recent reports point to a further worsening of disparities in clinical trial participation for minority populations over the past decade (583)Pittell H, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2322515. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](586)Riaz IB, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 180. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](594)IQVIA. Global Trends in R&D 2023. Accessed: March 17, 2024. (595)Dunlop H, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2239884. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

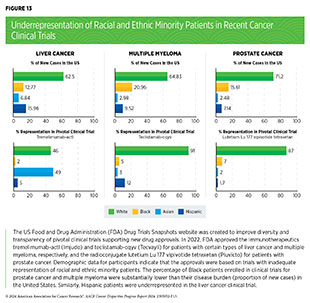

Analysis of FDA’s Drug Trials Snapshots website, which was created to improve diversity and transparency of pivotal clinical trials of newly approved drugs, indicates that many of the recently approved therapeutics were based on trials with inadequate representation of racial and ethnic minority participants (see Figure 13). A recent study that analyzed pivotal clinical trial data for 59 cancer therapeutics approved between 2012 and 2017 showed that only 40 percent of trials reported age and only 24 percent reported race and ethnicity of participants (596)Varma T, et al. (2023) BMJ Med, 2: e000395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. At the level of clinical trial funders, all sponsors reported the sex of enrolled participants. However, only 56 percent of sponsors adequately represented women. Forty percent of sponsors were transparent in reporting the age of participants and only 24 percent adequately represented older adults; only 24 percent of sponsors were transparent in reporting the racial and ethnic identity of participants for all pivotal trials and only 16 percent adequately represented patients from racial and ethnic minority populations (596)Varma T, et al. (2023) BMJ Med, 2: e000395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Representative study populations in clinical trials are critical to accurately determine the efficacy as well as potential toxicities of new treatments. Diversity among participants is even more vital during evaluation of cancer types with a disparately higher burden in specific populations, such as certain racial or ethnic minority groups, as well as during evaluation of cutting-edge precision medicine, e.g., molecularly targeted therapeutics or immunotherapeutics, because these treatments are closely tied to the unique characteristics of an individual’s cancer, immune system, lifestyle, and family history, among other factors (see Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Disparities).

Enrollment of participants from all sociodemographic backgrounds, as well as race- and ethnicity-specific reporting of the benefits and potential risks, can enable a comprehensive understanding of potential ancestry-related differences in cancer biology, disease biomarkers, or treatment responses including adverse events and ensure that newly approved anticancer agents can be safely used in the real-world setting.

Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation

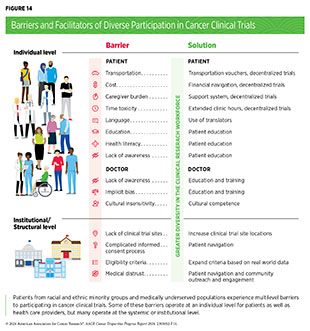

Numerous studies have investigated the existing barriers that limit participation of racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations in cancer clinical trials. Evidence indicates a range of structural barriers and societal injustices that operate at individual (patient and health care provider) and systemic (health care system) levels (see Figure 14). It is important to note that the patient-level barriers are often unique for each underserved population. For example, racial and ethnic minority populations may experience participation barriers due to lack of clinical trial awareness; lack of trust; lack of racial, ethnic, or language concordance with the clinical trial team; and pervasive systemic racism, while SGM groups may experience participation barriers primarily due to societal stigma and lack of standardized protocols and recruitment methods for this patient population (591)Rosser BRS, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 5093. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](600)Akimoto K, et al. (2023) Cancer J, 29: 310. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additional complexities may result from the social and cultural differences among different racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minority populations. Therefore, interventions to address barriers to clinical research must take into consideration the unique and specific experiences of the target population.

Individual-level barriers for patients include lack of understanding, awareness, or adequate information of clinical trials; limited health literacy; language barriers; mistrust of the health care system; and a fear of being placed in the control group, thereby not receiving the desired medical intervention (601)NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. Review of the Literature: Primary Barriers and Facilitators to Participation in Clinical Research. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . As one example, according to a recent study among Black patients with metastatic breast cancer, only 36 percent of patients said they received enough information from their health care team to make an informed decision about participating in a trial (602)Metastatic Breast Cancer Alliance. BECOME (Black Experience of Clinical Trials and Opportunities for Meaningful Engagement) Research Rreport. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Notably, more than 90 percent of patients indicated that they would be interested in learning about clinical trials and 83 percent were somewhat or very likely to consider participating.

Lack of health literacy, including limited understanding of clinical trials, has been reported as a barrier for participation in clinical trials (604)Hernandez ND, et al. (2021) J Cancer Educ, 37: 1589 [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Evaluation of barriers among Hispanic patients indicates that poor understanding of the purpose of a clinical trial, poor communication from health care providers, and fear of or uncertainty over experimental treatment may adversely affect their enrollment in clinical trials (605)Overcoming Barriers for Latinos on Cancer Clinical Trials. Accessed: April 22, 2022. . Low health literacy has also been reported as a barrier for parents while making informed decisions for their child’s participation in clinical research (606)Aristizabal P, et al. (2021) JAMA Network Open, 4: e219038. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Additional patient-level barriers include financial and time-related burdens, such as costs of cancer treatment and medication, transportation, childcare, lost work, and inadequate insurance or complete lack of it. These barriers are heightened in patients from racial and ethnic minority populations, who frequently report being the primary caregivers to family members and not having the time to participate in clinical trials; working in service occupations where it is difficult to get paid time off from work; and having more difficulties paying for health care, transportation, and other costs related to trial participation (607)Reopell L, et al. (2023) PLoS One, 18: e0281940. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Financial and time burdens of trial participation for minoritized and medically underserved patients must be considered during the design and implementation of clinical studies if we are to achieve equitable participation for all patients.

Many barriers exist at the provider level, including lack of knowledge of clinical trials and implicit biases such as health care providers perceiving minoritized patients as being less interested in participating compared to White patients (600)Akimoto K, et al. (2023) Cancer J, 29: 310. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](608)Coley AK, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: 154. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Implicit biases among health care staff and discrimination by providers who are responsible for recruiting patients in clinical trials can contribute to the exclusion of medically underserved populations (609)Andac-Jones E, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: e18675. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Evaluation of the impact of implicit bias on clinical trial recruitment and the utility of intervention strategies such as training curricula for addressing implicit bias in clinical research are areas of active investigation (610)Barrett NJ, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: e570. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Lack of dedicated staff to engage with and serve minority patient populations, time constraints for clinicians, and lack of cultural competence and effective communication skills are among the other provider-level factors that hinder diversity in clinical trial participation. A recent study evaluating the accrual of cancer patients in a molecularly targeted therapeutic clinical study showed that despite multiple notifications to physicians regarding patient eligibility based on tumor mutations, many patients were never informed of trial availability (611)Paydary K, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 863. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Considering that physicians are the most trusted source of clinical trial information for most racial and ethnic minority patients (575)Mesa R, et al. (2023) Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc, 133: 149. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], identifying ways to enhance physician motivation is vital for patient recruitment in clinical studies.

While evaluating clinical trial barriers and facilitators, researchers must give careful consideration to the adverse influences of all social drivers of health (SDOH), including poverty, food insecurity, housing insecurity, and psychosocial stressors throughout a patient’s life experience, even beyond clinical trial participation (see Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities). Such considerations are vital because research has shown that participation in clinical trials alone may not be enough to eliminate disparities in cancer outcomes (612)Unger JM, et al. (2021) J Clin Oncol, 39: 1339. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to a recent analysis, even among patients with breast cancer who participated in clinical trials, there were disparities in outcomes among certain groups, including young Black and Hispanic patients compared to their White counterparts (613)Lipsyc-Sharf M, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2339584. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Future research should examine how to eliminate additional sources of disparities that may be introduced through barriers or hardships prior to or following participation in clinical trials.

Beyond individual-level factors, there are barriers that operate at the level of the health care systems, as well as at the levels of the community and/or society. Many of these barriers are driven by structural inequities and social injustices (see Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities). Some of the major system-level and structural barriers include lack of trial availability, such as for patients like Melissa Adams who live in states or US territories that are far from mainland United States. Additional structural barriers include complexity of the clinical trials; time constraints for proper informed consent and clinical trial paperwork; complexities of consent documents; patient exclusion due to narrow eligibility criteria; medical distrust; lack of facilitators, such as translators or patient navigators; and lack of community engagement in low-resource settings.

Restrictive eligibility criteria often lead to exclusion of racial and ethnic minority patients from cancer studies (614)Riner AN, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2193. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent analysis of clinical trials submitted to FDA between 2006 and 2019 to support the approval of treatments for multiple myeloma showed that the ineligibility rates were higher for Black patients (24 percent) compared to White patients (17 percent) even though multiple myeloma incidence and mortality are highest among the US Black population (615)Kanapuru B, et al. (2023) Blood, 142: 235. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Research also shows that despite FDA’s efforts to expand certain eligibility criteria to improve diversity in patient enrollment, compliance with revised criteria remains poor (616)Riner AN, et al. (2023) JNCI Cancer Spectr, 7. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Research has shown that patients living in areas of higher disadvantage, characterized by lower income, education, employment, and housing quality, have a lower likelihood of enrollment in clinical trials (see Social and Built Environments) (617)Caston NE, et al. (2022) JCO Oncol Pract, 18: e1854. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Areas with high levels of deprivation tend to have a higher proportion of underrepresented racial and ethnic minority residents. Lack of trial availability in areas with a high proportion of racial and ethnic minorities restricts access to clinical studies. As one example, a recent analysis of 69 multiple myeloma clinical trials evaluating two different types of immunotherapies, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies, showed limited trial availability in states with the highest percentage of Black residents (618)Alqazaqi R, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2228877. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Three out of 10 states with the highest proportion of Black residents had no clinical trial openings.

According to a survey of clinical researchers, structural barriers such as distance to study sites and lack of involvement of community sites are the greatest barriers to diverse enrollment (584)Saez-Ibanez AR, et al. (2022) Nat Rev Drug Discov, 21: 870. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Most clinical studies are conducted at large academic cancer centers located in major metropolitan areas rather than smaller community-based cancer centers where nearly 85 percent of US patients receive their care (619)Harvey RD, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 1193. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These system-level barriers make clinical studies inaccessible to many populations, including patients living in rural and suburban parts of the country. As one example, despite the known efficacy of immunotherapeutics to improve outcomes for patients with metastatic melanoma, geographic access to clinical trials investigating these therapies remains a significant challenge for rural and Southern regions of the United States (620)Mulligan KM, et al. (2023) Arch Dermatol Res, 315: 1033. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Another known barrier to clinical trial enrollment for medically underserved patients, such as those from racial or ethnic minority populations, particularly those with limited English proficiency, is the informed consent process. Research shows that physicians may omit important information, including key specifics of the trial and the right to withdraw from a trial, during informed consent discussions with patients who do not speak English (622)Umaretiya PJ, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2346814. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While consent forms translated into a patient’s native language can, in part, improve patient satisfaction and facilitate the enrollment process, many studies do not have the financial resources for such services (623)Guo XM, et al. (2024) Gynecol Oncol, 180: 86. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](624)Velez MA, et al. (2023) Nature, 620: 855. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Limited health literacy can further compromise the consent process and prevent patients from making fully informed decisions about clinical study participation (625)Aristizabal P, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2346858. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Evidence-based interventions to enhance communication and reduce bias with patients from historically marginalized groups during informed consent discussions are needed to address the current inequities.

Facilitating Equity in Clinical Cancer Research

Overcoming barriers to clinical trial participation will require all constituents of the cancer research and care community to come together and develop multifaceted approaches that include the implementation of newer and more effective education and policy initiatives. Intervention strategies need to address barriers across all levels, from dismantling structural racism to catering to the individual needs of cancer patients. Ongoing research from academia, biopharmaceutical industry, nonprofit organizations, and federal agencies has identified many approaches that can facilitate enrollment of participants from diverse sociodemographic backgrounds (see Figure 14) (626)Odedina FT, et al. (2024) Mayo Clin Proc, 99: 159. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](627)Budhu JA, et al. (2023) Neuro Oncol: noad242. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](628)Oyer RA, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2163. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](629)Fashoyin-Aje LA, et al. (2023) Clin Cancer Res, 29: 3566. . The goals of these strategies are to improve access to clinical trials for diverse populations in the community, increase patient awareness and understanding of clinical research, build trust in communities, improve support of clinical trial sites and their health care staff, and report race/ ethnicity-related information while publishing clinical trial data. These goals align with the lifelong efforts of A. William Blackstock Jr., MD, Edith P. Mitchell, MD, and Worta McCaskill-Stevens, MD.

These interventions focus on a range of issues that include addressing SDOH (see Figure 3); decentralizing many of the trial activities to ease patient participation; expanding eligibility criteria; improving the efficiency of data collection, including patient-reported outcomes; enhancing community outreach and patient navigation efforts to raise awareness of trials; and improving patient-provider communication. One critical area of focus for the medical research community is fostering greater diversity, equity, and inclusion within the clinical research workforce so that the workforce will resemble the patient populations it serves (see Cancer Care Workforce Landscape). These efforts are vital because research shows that racial concordance between patients and health care providers can improve communication, trust, and adherence to medical advice and lead to better care (630)Loeb S, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2324395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](631)Kuri L, et al. (2023) Clin Trials, 20: 585. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Community Engagement and Patient Navigation

Research has shown that community outreach and patient navigation can enhance awareness of clinical trials and increase participation for racial and ethnic minority patients (180)Nouvini R, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128: 3860. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](632)An J, et al. (2023) Cancer: 1–17 . [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](633)Guerra CE, et al. (2021) Journal of Clinical Oncology, 39: 100. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Clinical researchers and institutions must implement strategies to include community-based partners in the design and execution of clinical trials and integrate patient and community feedback into clinical research design (626)Odedina FT, et al. (2024) Mayo Clin Proc, 99: 159. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](627)Budhu JA, et al. (2023) Neuro Oncol: noad242. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These efforts can build trust and credibility and facilitate relationship building and bidirectional communication, especially for populations that experience systemic injustices and discrimination and do not trust the clinical system.

It is also critical that research teams disseminate clinical trial results back to the communities. Policies to integrate community-based clinical partners such as local health care providers who may not traditionally participate in clinical research can further improve access to studies at the population level in underserved areas. Clinical institutions, sponsors, and researchers must support an infrastructure that sustains long-standing partnerships with the community, patients, and patient advocates (628)Oyer RA, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2163. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These actions can lead to fundamental changes to the clinical research landscape and ensure equitable participation.

Community engagement is particularly important for the inclusion of Indigenous populations and patients from tribal nations in clinical research. Research shows that AI/ AN patients have the lowest representation in clinical trials among all racial and ethnic groups (634)Mainous AG, 3rd, et al. (2023) Ann Fam Med, 21: 54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The role of the community is central to the AI/AN culture as highlighted in the personal story of Todd Gates. Research shows that incorporating the community perspective in a manner that considers cultural safety and humility may facilitate recruitment and retention in clinical research (634)Mainous AG, 3rd, et al. (2023) Ann Fam Med, 21: 54. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In this regard, a new framework, known as “Circle of Trust,” has been developed by AI/AN researchers who work with their communities for recruitment in clinical research. The model proposes interdependent and reciprocal relationships between patients, researchers, the communities, and trusted entities within the communities such as cultural leaders, elders, religious or spiritual leaders, traditional healers, tribal leaders, community leaders, traditional birth workers, community health workers, community health representatives, and tribal board members.

Patient navigators can provide social, emotional, and logistical support and act as a potential facilitating factor for clinical trial participation. As one example, a population health navigation program designed to address common barriers to cancer care for medically underserved populations, including insurance needs, food, clothing, housing, transportation, language, health literacy, social support, and missed appointments, was able to increase participation in clinical research (635)Strom C, et al. (2024) North Carolina Med J, 85: 0. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Prior to the initiation of the navigation program, only 19 percent of rural patients, 13 percent of Black patients, and 5 percent of Hispanic patients participated in clinical cancer studies. Among the navigated patient population, accrual in clinical trials rose to 40 percent, 41 percent, and 33 percent for rural, Black, and Hispanic patients, respectively (635)Strom C, et al. (2024) North Carolina Med J, 85: 0. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Researchers are evaluating whether tailored education and socioeconomic support using navigation can improve access to clinical trials. Patients who are Hispanic, Spanish-speaking, or publicly insured have limited access to facilities that deliver cell therapy for cancer (636)Hall AG, et al. (2023) Transplant Cell Ther, 29: 356 e1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A collaborative effort between a comprehensive cancer center and a safety net hospital system is using a multipronged approach including community outreach and patient navigation to guide patients, many of whom have low income, are uninsured, and are from racial and ethnic minority populations, through the process of enrolling in early-phase cell therapy trials and connecting them with relevant resources to address SDOH (637)Badr H, et al. (2023) Cancer Cell, 41: 2007. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While it remains to be seen whether this approach is able to expand cutting-edge clinical trials to medically underserved populations, researchers are hopeful that the program, if successful, could serve as a national model for enhancing health equity in cancer care.

Addressing System-level and Structural Barriers

While certain system-level barriers to clinical trial participation may require long-term strategies and effective policies, some could be addressed in the short term. One immediate approach could be to conduct clinical trials at facilities that treat a high percentage of racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved patient populations. Currently, many late-phase clinical trials are conducted outside the United States, and those within the United States are often limited to the high-volume cancer centers—facilities that treat higher numbers of patients, have specialty surgeons, and perform greater numbers of procedures—where patients from racial and ethnic minority groups rarely receive care (638)Kanapuru B, et al. (2017) J Clin Oncol, 35: 2539. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is, therefore, crucial that clinical studies be available to Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs), including at safety net hospitals, which often operate in inner-city communities and provide a larger share of care to low-income and uninsured populations. In fact, research has shown that more non-White patients enroll in clinical research sites in counties with higher proportions of non-White residents (631)Kuri L, et al. (2023) Clin Trials, 20: 585. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](639)Acoba JD, et al. (2022) Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 28: 100933. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

It is vital that researchers define adequate representation and set enrollment goals prior to the initiation of clinical studies (641)Varma T, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 765. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](642)Cullen MR, et al. (2023) Contemp Clin Trials, 129: 107184. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Equitable representation of a population group in a clinical trial should, at a minimum, match their disease burden rather than their proportion in the US population, but should ideally aim to represent groups in adequate numbers for subgroup-specific analyses (643)Bushueva NN (1989) Oftalmol Zh, 4: 194. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For instance, a multiple myeloma clinical trial should enroll at least 21 percent Black patients, based on the US disease burden—Black patients account for one-fifth of all new cases of multiple myeloma—instead of 12 percent of Black patients, based on the US Census—Black people make up 12.4 percent of the US population. Appropriate enrollment goals must also be justified prior to the recruitment process. This approach is vital, since a low enrollment of participants from a population subgroup may hinder accurate analyses of the safety and efficacy of a therapeutic in that group.

Additionally, clinical trial infrastructures must be set up to address social needs and alleviate common barriers such as food and housing insecurity, out-of-pocket costs, time off from work, and child and elder care. To encourage patients with cancer to participate in clinical studies, research teams need to reach out to and work with minority patient populations. Federal funding is critical to support infrastructures that enhance the accrual of minority patients on clinical trials.

The NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) is one example of federal efforts to reduce structural barriers for patients. NCORP is a national network that is successfully bringing cancer clinical trials and care delivery studies to people in their own communities in diverse settings. The program focuses on increasing clinical trial participation by addressing the structural and social drivers of disparities and evaluating differential outcomes in racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations (170)Arring N, et al. (2023) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 21: 481. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The participation of Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, and Native Hawaiian patients in cancer clinical studies at least as often or more frequently compared to White patients in an NCORP-affiliated center in Hawai‘i that obtains federal funding to enhance enrollment and provide all patients the same clinical trial opportunities highlights the importance of NCORP strategies (639)Acoba JD, et al. (2022) Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 28: 100933. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Another key strategy to diversify clinical trial participants is to simplify and expand eligibility criteria that often lead to exclusion of racial and ethnic minority patients. These criteria need to keep up with scientific innovation; be pragmatic, inclusive, and influenced by real-world evidence; and allow flexibility for patients with clinical or physical limitations (644)Grant MJ, et al. (2023) Nat Med, 29: 1908. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. If candidate anticancer therapeutics are to be given to a broad range of patients once approved, they should be tested in a broad range of patients, including those who may have coexisting medical conditions. In this regard, a recent study showed that expanding eligibility criteria for a pancreatic cancer clinical trial using real-world data derived from electronic health records and administrative claims equalized eligibility rates between Black and White patients (614)Riner AN, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2193. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, traditional eligibility criteria differentially excluded Black patients from participating in such trials (614)Riner AN, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2193. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

US policymakers and FDA are working on legislation and guidelines intended to increase the diversity of clinical trial participants (see Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Science-based Public Policy). These include a diversity action plan that would require researchers and funders of clinical trials to submit concrete goals and needed steps for enrolling specific demographic groups in pivotal studies of new drugs (645)Hwang TJ, et al. (2022) N Engl J Med, 387: 1347. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](646)U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants From Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials; Draft Guidance for Industry; Availability. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Continual monitoring of diversity plan submissions is required to benchmark whether ongoing and new clinical studies are consistently and adequately meeting their enrollment goals (647)US Food and Drug Administration. Project Equity. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . COVID-19, despite its adverse effects on all aspects of cancer research and patient care, provided an opportunity to decentralize clinical trial designs, so that lifesaving therapeutics could be brought quickly to as many patients as possible (648)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on Cancer Research and Patient Care. Accessed: June 30, 2022. .

Adaptations implemented by NCI and FDA during the pandemic to decentralize trials, including consenting patients remotely, permitting telehealth for routine clinical assessments, delivering experimental drugs to patients, and allowing the use of local laboratory or imaging facilities accessible to patients, have offered a blueprint of success to further revise and reform clinical research. Further efforts to build strong and sustainable partnerships between clinical research centers and local community practices and hospitals will be critical to ensure successful equitable implementation of decentralized clinical trials as well as continuity of care beyond clinical trial participation (619)Harvey RD, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 1193. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

It is important, however, to rigorously examine whether decentralized clinical trials can ensure equal access to trial participation for all population groups to avoid widening of existing inequities. For example, it is possible that by eliminating the barriers to participation such as transportation and geographic constraints, those groups who already participate in clinical research may enroll at higher rates, making trial participants even less diverse and representative of the real-world disease burden (650)Dahne J, et al. (2023) JAMA, 329: 2013. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Inequities in Cancer Treatment

The dedicated efforts of individuals working throughout the medical research cycle (see Figure 4) are constantly translating new research discoveries into advances in cancer treatment that are improving survival and quality of life for people in the United States and around the world. Much of the recent progress, including many new cancer treatments approved by FDA, was highlighted in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2023 (1)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2023. Accessed: Feb 29, 2024. .

Despite these advances, racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations continue to experience more frequent and higher severity of multilevel barriers to quality cancer treatment, including treatment delays, lack of access to guideline-adherent treatment, undertreatment, refusal or early termination of treatment, treatment receipt at low-volume and community settings rather than comprehensive cancer centers, and higher rates of treatment-related and/or financial toxicities (see Sidebar 28) (651)Ubbaonu CD, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 5586. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](652)Winn R, et al. (2023) J Natl Med Assoc, 115: S2. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](653)Obeng-Gyasi S, et al. (2023) J Racial Ethn Health Disp, DOI: 10.1007/s40615-023-01788-y. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](654)Yousefi Nooraie R, et al. (2022) Front Health Serv, 2: 1113916. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](655)Sheni R, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: e904. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As one example, based on a recent analysis, Black and Hispanic patients with triple-negative breast cancer are 18 percent and 13 percent less likely, respectively, to receive guideline-adherent treatment (including surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy) compared to White patients (651)Ubbaonu CD, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 5586. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Patients from racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations report experiences of overt discrimination and/or implicit bias during the delivery of care, including negative experiences with their health care providers (656)Schatz AA, et al. (2022) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 20: 1092. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Better experiences while accessing care may mitigate racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of guideline-adherent treatment (657)Navarro S, et al. (2023) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 22: e237074. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, oncologists rarely perceive racial anxiety or unconscious bias as adversely influencing clinical care or survival outcomes for minoritized patients (657)Navarro S, et al. (2023) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 22: e237074. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Implementing health system interventions to increase institutional awareness of the current challenges and ensuring that the cancer care workforce is cognizant of their own perceptions surrounding racial disparities and biases is vital to achieving health equity.

Many of the inequities in cancer care can be attributed to adverse differences in SDOH, including low income, lack of health insurance, and limited access to health care facilities (see Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities). Research shows that patients with high household income deem cure as a priority when choosing treatment options, whereas those with lower income prioritize additional factors beyond cure such as cost, duration, effect on daily activities, and burden on family and friends (669)Rock C, et al. (2023) JNCI Cancer Spectr, 7: pkad032. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Barriers to quality cancer treatments are compounded for Indigenous populations and those living in remote or rural areas, as well as for patients who lack health literacy or have language barriers (655)Sheni R, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: e904. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](663)Liu X, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2251524. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](670)Reeder-Hayes KE, et al. (2023) Cancer, 129: 925. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](671)Pandit AA, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 1939. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Evidence suggests that receiving health care from a provider who is of the same race and/or ethnicity or speaks the same language as the patient can improve patient satisfaction and quality of care (630)Loeb S, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2324395. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](672)Bregio C, et al. (2022) JCO Oncol Pract, 18: e1885. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](673)Takeshita J, et al. (2020) JAMA Netw Open, 3: e2024583. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, fewer individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups report having the same race and/or ethnicity or language preference as their provider (114)KFF. Survey on Racism, Discrimination and Health: Experiences and Impacts Across Racial and Ethnic Groups. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Dissatisfaction with their health care due to experiences of discrimination and cultural incompetency is a major barrier for patients from SGM populations and often leads to avoidance of care (674)Russell S, et al. (2022) Clin J Oncol Nurs, 26: 183. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](675)Chan ASW, et al. (2023) Soc Work Health Care, 62: 263. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Based on a recent report, patients with breast cancer from SGM groups are more than twice as likely to decline an oncologist-recommended treatment modality compared with cisgender heterosexual patients (67)Clifford GM, et al. (2021) Int J Cancer, 148: 38. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is also serious lack of data on the quality of the cancer care received by SGM patients, making it difficult to accurately assess the disparities in cancer treatment and continuity of care among these patients (676)Kamen CS, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: 959. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](676).

It should be noted that patients with intersectional identities often experience multilevel barriers to cancer care that adversely impact screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. As one example, recent data show that Black and AI/AN populations living in rural areas experience greater poverty and lack of access to quality care, both of which expose them to a greater risk of experiencing poorer cancer outcomes (677)Zahnd WE, et al. (2021) Int J Environ Res Pub Health, 18: 1384. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is a critical need for additional research to understand the intersections of geography, race/ethnicity, socioeconomics, sexual orientation, and gender identity and their effects on disparities in cancer treatment and to mitigate these disparities through reduced structural and interpersonal biases, increased access, and implementation of evidence-based interventions.

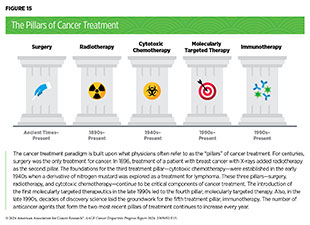

In the following sections, we highlight recently documented inequities among cancer patients from racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations in the use of the main pillars of cancer treatment (see Figure 15) and highlight areas where advances have been made in achieving equity in cancer treatment. Importantly, several recent studies have pointed out that disparities in the receipt of care, as well as outcomes for many cancers, can be eliminated if every patient has equitable access to quality health care services (115)Darmon S, et al. (2023) Health Equity, 7: 178. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](678)Dong J, et al. (2022) Blood Cancer J, 12: 34. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](679)Gong J, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 228. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Treatment With Surgery

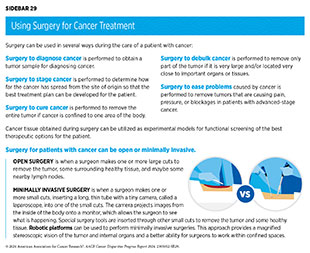

Surgery, radiotherapy, and cytotoxic chemotherapy are three pillars of cancer treatment (see Figure 15) that form the foundation of initial clinical care for almost all patients with cancer. Surgery is the foundation of treatment for many cancer types (see Sidebar 29) for which there are significant disparities in mortality and morbidity experienced by racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations.

For cancers associated with high mortality, such as lung, liver, and pancreatic cancers, surgical resection is key to survival when these tumors are detected at an early stage. For cancers with better prognosis, specialty surgeries are necessary to optimize quality of life after the treatment, such as minimally invasive surgery for gastrointestinal cancers, reconstruction surgery for certain breast cancer patients requiring mastectomy, and sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer patients. Researchers are continuously innovating new and improved strategies to maximize the benefit and minimize harms from surgery for cancer patients. Thanks to such efforts, overall mortality rates after surgery for all patients with many common types of cancer have declined over the past decade (680)Lam MB, et al. (2020) JAMA Netw Open, 3: e2027415. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, the mortality gap between Black and White patients after surgery, overall, or for individual cancer procedures, has not narrowed (680)Lam MB, et al. (2020) JAMA Netw Open, 3: e2027415. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

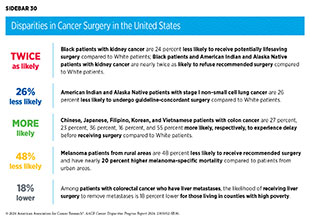

Racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations often experience disparities in surgical management of cancer, including treatment delays or refusals and lack of guideline-adherent care (see Sidebar 30). These disparities are seen across many cancer types, including the most diagnosed cancers in the United States, and may contribute to worse outcomes. As one example, NH Black women with breast cancer are less likely to receive curative surgery and NH Black as well as Hispanic women with breast cancer have higher odds of delayed surgery compared to non-Hispanic White women (681)Stabellini N, et al. (2023) Sci Rep, 13: 1233. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](682)Fwelo P, et al. (2023) Breast Cancer Res Treat, 199: 511. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Among patients with colorectal cancer, NH Black patients are more likely to undergo emergency surgery compared to NH White patients (683)Howard R, et al. (2023) Ann Surg, 278: e51. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Undergoing emergency surgery is indicative of barriers to timely screening and evaluation and is associated with increased likelihood of postoperative complications, including mortality.

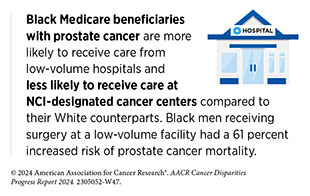

For cancers associated with high mortality, such as glioblastoma multiforme (an aggressive form of brain tumor) or pancreatic cancer, surgical resection is key to survival. Unfortunately, research shows that US counties with a higher percentage of Black patients have delays in surgical care, attributed to lack of neurosurgeons, as well as lower overall rates of surgery for glioblastoma (688)Ramapriyan R, et al. (2023) Neurosurg Focus, 55: E12. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Cancer patients from racial and ethnic minority populations are often treated at community and minority-serving hospitals. Patients with pancreatic cancer treated at minority-serving hospitals have lower rates of surgical resection, a decreased likelihood of undergoing curative surgery, and increased mortality (689)Olecki EJ, et al. (2024) J Surg Res, 294: 160. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Despite the immense benefits of surgery in cancer, complications are common and can negatively affect a patient’s quality of life. One approach to reducing the complications during and after surgery and improving quality of life post procedure is to perform minimally invasive surgeries, such as robotic surgeries, that are performed by highly specialized surgeons.

Unfortunately, there are disparities in the use of these cutting-edge procedures and in the access to specialized surgeons. As one example, patients with lung cancer who are Black, have Medicaid insurance, are treated at smaller hospitals, or are from rural areas, are less likely to be treated by a specialized thoracic surgeon (690)Halloran SJ, et al. (2023) Curr Oncol, 30: 2801. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A recent review that evaluated the use of robotic and minimally invasive surgeries in patients with prostate, endometrial, bladder, or rectal cancer found that 70 percent of current studies reported lower use of these state-of-the-art procedures among Black patients and 50 percent of all studies reported lower use among Hispanic patients compared to White patients (691)Mao J, et al. (2024) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 33: 20. . According to another analysis, among patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), those who live in low-income neighborhoods or receive care at community hospitals are significantly less likely to undergo minimally invasive surgeries (692)Sakowitz S, et al. (2023) J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 165: 1577. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, patients without private health insurance are less likely to receive robotic surgeries (693)Childers CP, et al. (2023) Ann Surg Oncol, 30: 3560. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Lack of or limited access to surgical facilities is a major barrier in seeking cancer surgery. It is known that a greater distance to a surgical facility is associated with a decreased likelihood of treatment (694)Tang C, et al. (2021) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 109: 1286. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Patients from the rural United States are particularly vulnerable, since they must travel significantly longer distances for care (695)Honaker MD, et al. (2023) Ann Surg Oncol, 30: 3547. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This may result in delay or lack of needed surgeries (671)Pandit AA, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 1939. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](696)Logan CD, et al. (2023) J Surg Res, 283: 1053. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As one example, patients with pancreatic cancer from rural areas are 12 percent less likely to undergo pancreatectomy and have a 25 percent higher 1-year mortality compared to metropolitan residents (697)Brooks GA, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 1171. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These disparities are driven largely by socioeconomic factors and could be exacerbated in patients from racial and ethnic minority populations living in rural areas. According to a recent study, patients with colon cancer from racial and ethnic minority groups who resided in rural areas experienced higher odds of postoperative surgical complications and mortality, with Black patients from rural areas experiencing 86 percent higher odds of postoperative mortality compared to their metropolitan counterparts (698)Ramkumar N, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2229247. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Many of the inequities in cancer surgery are driven by centuries of structural and systemic injustices. As one example, research has shown that women with breast cancer living in historically redlined areas are less likely to receive surgery and have higher breast cancer–specific mortality compared to those not living in such areas (103)Bikomeye JC, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 652. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It has been demonstrated that receiving specialized treatments such as complex cancer surgeries at high-volume hospitals is associated with better outcomes compared to low-volume hospitals (699)Ghauri MS, et al. (2023) Cureus, 15: e37112. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](700)Sebastian N, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2327637. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Patients living in redlined areas are less likely to receive surgery at high-volume hospitals because of socioeconomic challenges (701)Khalil M, et al. (2024) Ann Surg Oncol, 31: 1477. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Inequities in quality surgical care can be attributed to adverse influences of SDOH, including low income or education levels, lack of health insurance, and transportation challenges. A retrospective analysis identified lower median household income and nonprivate health insurance as two of the factors associated with not undergoing surgery for patients with rectal cancers (703)Chen SY, et al. (2023) Surgery, 174: 1323. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similar results have been found among patients with lung cancer (704)Bassiri A, et al. (2024) J Surg Res, 293: 248. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study looking at the receipt of surgery among women with certain gynecologic cancers found higher rates of treatment refusal among patients who were uninsured, lived in regions with low rates of high school graduation, or were treated at a community hospital (705)Samuel D, et al. (2023) Gynecol Oncol, 174: 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Notably, overall survival rates are lower among patients who refuse surgery.

Taken together these studies highlight the need for multilevel interventions to ensure equitable delivery of guideline-recommended surgery for all cancer patients. All constituents must work together to improve access to quality health care resources for all patients while continuing further research into the mechanisms that perpetuate disparities. In this regard, an urgent unmet need is to capture and integrate SOGI data in the surgical literature to understand the extent of perioperative disparities these patients may experience (706)Broekhuis JM, et al. (2023) JAMA Surg, 158: 111. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, concerted efforts from the medical research community and policymakers are needed to diversify the current surgical oncology workforce, which significantly lacks representation from minoritized groups and women (707)Morrow M, et al. (2022) Ann Surg Oncol, 29: 2136. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Treatment With Radiation Therapy

Radiotherapy is the use of high-energy rays (e.g., gamma rays and X-rays) or particles (e.g., electrons, protons, and carbon nuclei) to control or eradicate cancer. The discovery of X-rays in 1895 allowed visualization of internal organs at low doses, and the effective use of X-rays at high doses to treat a patient with breast cancer a year later established radiotherapy as the second pillar of cancer treatment (see Figure 15). Radiotherapy plays a central role in the management of cancer and works primarily by damaging DNA, leading to cancer cell death. The use of radiotherapy in the treatment and management of cancer continues to increase, as indicated by a 16.4 percent increase in radiation facilities across the United States between 2005 and 2020 (708)Maroongroge S, et al. (2022) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 112: 600. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are many types and uses of radiotherapy (see Sidebar 31). Approximately 50 to 60 percent of patients with cancer receive radiotherapy at some point during their disease course (709)Delaney G, et al. (2005) Cancer, 104: 1129. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](710)Chierchini S, et al. (2019) Cancer Manag Res, 11: 8829. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, it is important to note that radiotherapy may also have harmful side effects, partly because of the radiation-induced damage to healthy cells surrounding the tumor tissue.

Researchers are continuously working on making radiotherapy safer and more effective. As one example, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy is an advanced approach to radiotherapy that can more precisely target radiation to tumors than conventional forms of external beam radiotherapy (see Sidebar 31). As a result, higher doses of radiation can be used without damaging healthy tissues surrounding a tumor, which reduces the long-term adverse effects of radiotherapy. Recent clinical trials have shown that stereotactic ablative radiotherapy targeted to certain metastatic tumors can reduce the chances of disease progression and increase survival for patients who have solid tumors, such as prostate cancer, lung cancer, and gastrointestinal tumors (711)Sengupta R, et al. (2020) Clin Cancer Res, 26: 5055. . Researchers are also designing novel radiotherapeutics, such as molecularly targeted radioconjugates, to be used alone or in combination with other treatments, to target more cancer types and benefit more patients (89)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2023. (712)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2018. Accessed: June 30, 2022. .

Another area of active investigation is identifying when radiotherapy can be reduced or avoided without affecting the chances of survival for patients. In this regard, a recent clinical trial showed that for patients with early-stage prostate cancer, active monitoring of their disease is a safe alternative to receiving immediate surgery or radiotherapy (713)Hamdy FC, et al. (2023) N Engl J Med, 388: 1547. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The study directly compared the long-term outcomes of three approaches, prostate removal surgery, radiotherapy, or active monitoring, and found that there was no difference in prostate cancer mortality at the 15-year follow-up between the three groups. These data provide hope for patients with prostate cancer who opt for active monitoring to avoid treatment-related adverse effects, such as sexual and incontinence problems. Recent findings show that uptake of active monitoring has increased nationally but remains suboptimal, with wide disparities across health care practices (714)Cooperberg MR, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e231439. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

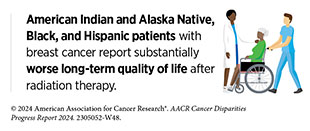

Unfortunately, reduced access to and utilization of radiation therapy, including as curative treatments, have been well documented among patients from racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States (715)Chen AM (2023) Front Health Serv, 3: 1288329. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](716)Verdini NP, et al. (2024) Am J Clin Oncol, 47: 40. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](717)Gardner U, Jr., et al. (2022) Adv Radiat Oncol, 7: 100943. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], which contributes to disparities in cancer outcomes. As one example, a retrospective analysis of the National Cancer Database showed that Black women with cervical cancer and NHOPI women with endometrial cancer were significantly less likely to receive brachytherapy compared to NH White women and that for both Black and NHOPI women, treatment at community cancer centers was associated with a decreased likelihood of brachytherapy (718)Taparra K, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15: 2571. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study evaluating patients with head and neck cancer showed that racial and ethnic minority patients were more likely to experience delays in the receipt of adjuvant radiation (719)Chen AM, et al. (2023) Oral Oncol, 147: 106611. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, non–English-speaking patients and those from low SES were more likely to experience such delays. The likelihood of missing radiation therapy appointments has been shown to be nearly three times higher among Black, Hispanic, and low-income patients (715)Chen AM (2023) Front Health Serv, 3: 1288329. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

A recent advance in radiation oncology is the emergence of hypofractionated radiotherapy, whereby patients receive fewer but higher doses of radiotherapy compared with the traditional course. Hypofractionated radiotherapy is increasingly being used in the treatment of breast cancer and prostate cancer because it has shown similar efficacy in improving long-term outcomes as traditional courses of radiotherapy (721)Niazi TM, et al. (2022) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 114: S3. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](722)Haviland JS, et al. (2013) Lancet Oncol, 14: 1086. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](723)Avkshtol V, et al. (2020) J Clin Oncol, 38: 1676. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Patients who have hypofractionated radiotherapy complete their treatment over a shorter period and in fewer sessions.

Hypofractionated regimens could potentially benefit underserved patients by reducing travel-related financial and time burdens. In fact, recent studies indicate that across racial and socioeconomic populations, timely completion of radiation therapy is greater for patients with breast cancer receiving hypofractionated radiation compared to those receiving traditional radiation (724)Lamm R, et al. (2022) Surgery, 172: 31. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, racial disparities in treatment noncompletion between Black and White patients with breast and prostate cancer were drastically reduced with shorter radiation regimens (725)Dee EC, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: e197. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is also encouraging that over the past two decades, there has been an increase in the utilization of shorter radiation regimens, such as hypofractionated radiotherapy and stereotactic body radiotherapy, across all populations (726)Ganesh A, et al. (2023) Clin Lung Cancer, 24: 60. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](727)Qureshy SA, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2337165. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, treatment disparities persist, with evidence that Black patients are less likely to receive hypofractionated radiation (725)Dee EC, et al. (2023) JCO Oncol Pract, 19: e197. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](727)Qureshy SA, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2337165. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](728)Liu Q, et al. (2024) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev: , 33: 489. .

Researchers have identified a range of barriers, including socioeconomic status, geographic location, insurance status, language, and health care facility characteristics, that contribute to the disparities in radiation therapy access and utilization. Based on a recent report, hospitals serving racial and ethnic minority groups are significantly less likely to offer many core cancer services, including diagnostic radiology for cancer detection, many radiotherapy modalities, and other treatment modalities (110)Himmelstein G, et al. (2024) JAMA Oncol, 10: 134. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

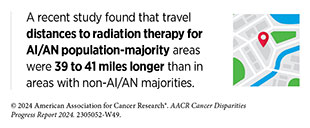

One the most prominent barriers to receiving radiation therapy lies in geographic location and access (or lack thereof) to clinical facilities. Regions with greater geographic access to radiation therapy tend to have residents who are of higher socioeconomic status and are better insured (708)Maroongroge S, et al. (2022) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 112: 600. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Increasing travel distances to treatment facilities are associated with lower receipt of radiation treatment (729)Beckett M, et al. (2023) JCO Glob Oncol, 9: e2300130. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](730)Arega MA, et al. (2021) J Clin Oncol, 39: 24. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Greater distance to radiation therapy facilities and fewer radiation oncologists in an area have been shown to be associated with higher cancer mortality (729)Beckett M, et al. (2023) JCO Glob Oncol, 9: e2300130. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](731)LaVigne AW, et al. (2023) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 116: 17. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Patients from Indigenous populations and rural areas are at a particularly higher risk of living farther away from radiation facilities and not receiving needed treatments (732)Lui G, et al. (2022) Adv Radiat Oncol, 7: 101017. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Overall, these findings call for new evidence-based strategies to improve access to radiotherapy services for patients with cancer from all medically underserved populations. It is imperative that all constituents in medical research and public health come together to identify populations and areas with the greatest barriers to radiation care, investigate the underlying barriers, and develop tailored interventions with the goal of reducing health inequities in radiotherapy.

Treatment With Chemotherapy

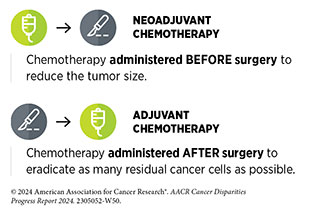

Cytotoxic chemotherapy is the use of chemicals to kill cancer cells and was first introduced as a pillar of cancer treatment in the early to mid-20th century (734)DeVita VT, Jr., et al. (2008) Cancer Res, 68: 8643. . Chemotherapy can be extremely effective in systemic treatment of cancer. It remains a backbone of cancer treatment, and its use is continually evolving to minimize potential harm to patients with cancer, while maximizing its benefits.

Treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapeutics can have adverse effects on patients. These effects can occur during treatment and continue in the long term, or they can appear months or even years later. Health care providers and researchers are investigating different approaches to make chemotherapeutics safer for patients. Areas of ongoing investigation include designing modifiable chemotherapeutics, e.g., with “on” and “off ” switches, that are selectively delivered to tumors while sparing healthy tissue; evaluating less aggressive chemotherapy regimens that can allow patients the chance of an improved quality of life without compromising survival; and identifying specific molecular characteristics in tumors called biomarkers to correctly predict which patients will or will not benefit from chemotherapy (735)East P, et al. (2022) Nat Commun, 13: 5632. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](736)Rais R, et al. (2022) Sci Adv, 8: eabq5925. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](737)Kotani D, et al. (2023) Nat Med, 29: 127. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

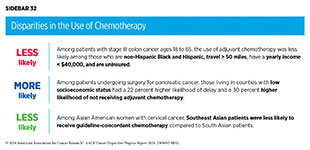

Unfortunately, many reports have documented that cancer patients from racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations are less likely to receive recommended chemotherapy (see Sidebar 32). Medically underserved patients are also more likely to decline physician-recommended chemotherapy (738)Jabbal IS, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These disparities arise due to a range of socioeconomic disadvantages, including low income, lack of health insurance, being treated at community hospitals, language barriers, and clinical factors such as advanced age.

As one example, a recent study that examined racial disparities in treatment among Black and White patients ages 18 to 49 with colorectal cancer found that Black patients were more likely to not receive guideline-adherent care in part because of lack of health insurance (739)Nogueira LM, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol: JCO2300539. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Compared to White patients, Black patients with colon cancer were 22 percent more likely to not receive chemotherapy, while Black patients with rectal cancer were 68 percent more likely to not receive chemotherapy. Black patients also experienced greater delays before receiving the needed chemotherapy. These findings are concerning considering the rising incidence of colorectal cancer among individuals younger than 50 years (early-onset colorectal cancer) (740)Siegel RL, et al. (2023) CA Cancer J Clin, 73: 233. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](741)Giannakis M, et al. (2023) Science, 379: 1088. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] and evidence that Black patients with early-onset colorectal cancer tend to have worse outcomes compared to White patients. Understanding the reasons behind rising cases of early-onset colorectal cancer and addressing this trend for all populations are areas of intensive research.

While it is vital for the medical research community to address the inequities in access to cancer chemotherapy for racial and ethnic minority patients, it is also critical to carefully evaluate the disparities in chemotherapeutic responses, including differences in toxicities that have been reported in the literature, since they impact patient outcomes and quality of lives (745)Rosenzweig MQ, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 157. (746)Pathak S, et al. (2023) Cancer Rep (Hoboken), 6 Suppl 1: e1830. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

For patients with breast cancer, the presence or absence of three tumor biomarkers, two hormone receptors (HR) and the protein HER2, determines what treatment options should be considered. About 70 percent of breast cancers diagnosed in the United States are characterized as HR-positive and HER2-negative. Based on recent reports, Black patients with nearly every subtype of breast cancer tended to have worse responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (747)Zhao F, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e233329. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](748)Shubeck S, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e235834. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]; the disparity was most pronounced in patients with HR-negative, HER2-positive tumors. Researchers found biological differences in the tumors from Black patients that rendered them resistant to chemotherapeutics. These findings highlight the importance of identifying appropriate biomarkers in making treatment decisions. It is imperative that cancer biomarkers are evaluated in patients from all sociodemographic backgrounds, considering the evidence that certain biomarker-driven tests currently used to measure breast cancer aggressiveness and make decisions on chemotherapy treatment are less accurate for Black women than for White women (749)Hoskins KF, et al. (2021) JAMA Oncology, 7: 370. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](750)Collin LJ, et al. (2019) NPJ Breast Cancer, 5: 32. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Treatment With Molecularly Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy

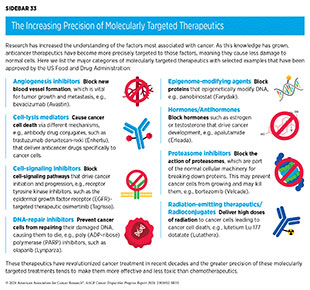

Remarkable advances in our understanding of the biology of cancer, including the identification of numerous genetic mutations that fuel tumor growth, set the stage for a new era of precision medicine, an era in which the standard of care for many patients is changing from a one-size-fits-all approach to one in which greater understanding of the individual patient and characteristics of their cancer dictates the best treatment option for the patient. Therapeutics directed to the molecules influencing cancer cell multiplication and survival target the cells within a tumor more precisely. The greater precision of these molecularly targeted therapeutics tends to make them more effective and less toxic than chemotherapeutics (see Sidebar 33). Molecularly targeted therapeutics have become the fourth pillar of cancer care and are not only saving the lives of patients with cancer but are also allowing these individuals to have a better quality of life.

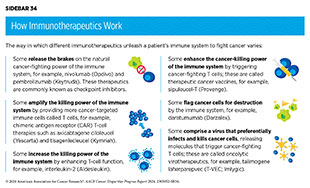

Groundbreaking basic research in the field of immunology—the study of the immune system—has laid the foundation of modern immunotherapy. Cancer immunotherapeutics leverage the natural ability of the immune system to fight cancer. There are various ways in which different immunotherapeutics unleash the immune system to fight cancer (see Sidebar 34).

In recent years, immunotherapy has emerged as the fifth pillar of cancer care and as one of the most exciting new approaches to cancer treatment along with molecularly targeted therapeutics. This is, in part, because many patients with metastatic cancer who have been treated with these revolutionary treatments have had remarkable and durable responses. In fact, the rapid advances in the field of molecularly targeted therapeutics and immunotherapeutics have transformed the treatment landscape for patients with formerly intractable cancers such as NSCLC or metastatic melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. As reported in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2023, dramatic reductions in lung cancer and melanoma death rates in recent years, due in part to molecularly targeted therapeutics and immunotherapeutics, are largely responsible for the steady decline in overall age-adjusted US cancer death rates (1)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2023. Accessed: Feb 29, 2024. .

The effective use of molecularly targeted therapeutics and immunotherapeutics often requires tests called companion diagnostics. Companion diagnostics detect specific molecular abnormalities, e.g., genetic mutations within tumors, often referred to as biomarkers, to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from the corresponding targeted therapy. This also allows patients identified as very unlikely to respond to forgo treatment and thus be spared any adverse side effects.

Unfortunately, there are striking inequities in the utilization of molecularly targeted therapeutics and immunotherapeutics which form the foundation of cancer precision medicine (652)Winn R, et al. (2023) J Natl Med Assoc, 115: S2. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These disparities are observed for most cancers, including those with a disparate burden among patients from racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations. Black women with breast cancer have a 40 percent higher mortality, while Black men with prostate cancer have a nearly two-fold higher mortality compared to their White counterparts (see Cancer Disparities Experienced by US Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations). While differences in tumor molecular characteristics may contribute to some of these disparities, there are known inequities in the receipt of molecularly targeted therapeutics, that also play a significant role.

Patients with HR-positive and HER2-negative breast cancers are treated with a class of molecularly targeted therapeutics known as hormone therapies or endocrine therapies, which work by lowering the levels or preventing the function of the hormone estrogen. Hormone therapies can be used prior to initial breast cancer surgery (neoadjuvant), as initial treatment, or following surgery to be continued for 5 years or longer (adjuvant), depending on a patient’s tumor characteristics.

Based on a recent analysis of patients with breast cancer who are 18 years or older, NH Black patients have a 17 percent lower likelihood of being prescribed endocrine therapy and have a significantly longer delay to initiation of endocrine therapy when prescribed, compared to White patients (681)Stabellini N, et al. (2023) Sci Rep, 13: 1233. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. NH Black patients also have lower odds of adhering to recommended treatments and continuing adjuvant endocrine therapy compared with NH White patients (751)Sood N, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2225345. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Higher severity in adverse physical and psychological symptoms from adjuvant endocrine therapy may contribute to lower treatment adherence among Black women with breast cancer (752)Hu X, et al. (2022) JAMA Netw Open, 5: e2225485. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Another treatment option for patients with HR-positive and HER2-negative breast cancer is a molecularly targeted therapeutic that works by blocking the function of two specific proteins that play a role in driving cell multiplication—cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4 and CDK6. There are three CDK4/6-targeted therapeutics that are approved by FDA to be used in combination with hormone therapy for treatment of patients with breast cancer. Long-term follow-up of these patients has shown that this combination approach improves overall survival (754)Goyal RK, et al. (2023) Cancer, 129: 1051. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](755)Neven P, et al. (2023) Breast Cancer Res, 25: 103. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Unfortunately, there is evidence that the use of CDK4/6-targeted therapeutics is lower among patients who are Black and from lower SES (756)Sathe C, et al. (2023) Breast Cancer Res Treat, 200: 85. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Use of CDK4/6-targeted therapeutics is twice as high among patients treated at academic cancer centers compared to those treated at community centers, where the majority of underserved patients receive care.

The growth of most prostate cancers is fueled by hormones called androgens. This knowledge led researchers to develop molecularly targeted therapeutics that lower androgen levels in the body or prevent its function. This approach to prostate cancer treatment is another type of hormone therapy called androgen-deprivation therapy. Unfortunately, most prostate cancers that initially respond to androgen-deprivation therapy eventually begin to grow again. To address this challenge, researchers have developed a new generation of hormone therapeutics that more effectively deprive prostate cancer of androgens. These treatments have been shown to prolong overall survival for patients with advanced prostate cancer. However, recent data indicate that the use of these novel hormone therapeutics is not similar across all populations, with decreased utilization observed in Black patients compared with other racial and ethnic groups, likely due to multilevel barriers, including adverse SDOH (757)Ma TM, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2345906. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].