Disparities in Cancer Treatment

In this section you will learn:

- Research is driving progress across all five pillars of cancer treatment: surgery, radiation, cytotoxic chemotherapy, molecularly targeted therapy, and immunotherapy.

- Clinical trials establish whether new cancer treatments are safe and effective for everyone who will use them if they are approved, so it is concerning that there is a serious lack of racial and ethnic diversity among clinical trial participants.

- Despite the advances in cancer treatment, patients from certain population groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, are less likely to receive the standard of care recommended for the type and stage of cancer with which they have been diagnosed.

- Several recent studies have shown that racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes for several types of cancer, including prostate cancer and multiple myeloma, can be eliminated if every patient has equal access to standard treatment.

- Researchers are working to identify innovative strategies to ensure that all patients can participate in cutting-edge clinical trials and receive standard treatments.

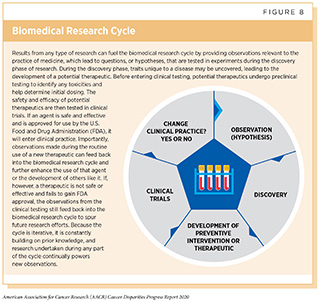

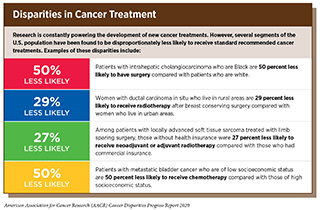

The dedicated efforts of individuals working throughout the cycle of biomedical research are constantly powering the translation of new research discoveries into advances in cancer treatment that are improving survival and quality of life for people in the United States and around the world (see Figure 8). Much of the most recent progress was highlighted in the AACR Cancer Progress Report 2019, which documented a record number of new cancer treatments approved by the FDA in the 12 months covered in that edition of the annual report to treat several types of cancer (115)AACR Cancer Progress Report 2019.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Despite these advances in clinical care, individuals from certain population groups including racial and ethnic minorities continue to experience more frequent and higher severity of multilevel barriers to quality cancer treatment including lack of access to guideline-concordant treatment (223)American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Cancer Disparities: A Chartbook. Strategies [Internet]. 2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see sidebar on Disparities in Cancer Treatment). The same population groups may also experience overt discrimination and/or implicit bias in the delivery of care (253)Penner LA, Blair I V, Albrecht TL, Dovidio JF. Reducing Racial Health Care Disparities: A Social Psychological Analysis. Policy insights from Behav brain Sci [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 17];1:204–12.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Disparities in cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities can be attributed to obstacles in accessing quality health care services, including cutting-edge cancer treatments. The obstacles range from lack of or inadequate health insurance coverage, to low socioeconomic conditions, to transportation difficulties, and to lack of health literacy (223)American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Cancer Disparities: A Chartbook. Strategies [Internet]. 2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

These multilevel factors result in racial and ethnic minority populations experiencing greater incidence and mortality from of a number of types of cancers due to delayed diagnosis, a more advanced stage of disease at diagnosis, more rapid progression to aggressive disease, increased rates of development of treatment resistance, higher cancer-specific and cancer-related mortality rates, and worse survival. Each of the potential drivers of disparity can also have a negative impact on responses to both standard treatment and/or novel agents being evaluated in clinical trials. Furthermore, it has been consistently documented that racial and ethnic minorities are underrepresented in clinical trials of new anticancer therapeutics, even for trials that are aimed at cancer types with a disproportionately higher burden among those population groups (257)Duma N, Vera Aguilera J, Paludo J, Haddox CL, Gonzalez Velez M, Wang Y, et al. Representation of Minorities and Women in Oncology Clinical Trials: Review of the Past 14 Years. J Oncol Pract [Internet]. 2017;14:JOP.2017.025288.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(258)Nazha B, Mishra M, Pentz R, Owonikoko TK. Enrollment of Racial Minorities in Clinical Trials: Old Problem Assumes New Urgency in the Age of Immunotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ book Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet [Internet]. American Society of Clinical OncologyAlexandria, VA; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];39:3–10.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Here, we highlight the major disparities among racial and ethnic minorities in clinical research participation as well as in the use of the main pillars of cancer treatment (see Figure 9). It is important to note that several recent studies have pointed out that disparities in outcomes for many cancers can be eliminated if every patient has equivalent access to standard treatment (259)Fillmore NR, Yellapragada S V, Ifeorah C, Mehta A, Cirstea D, White PS, et al. With equal access, African American patients have superior survival compared to white patients with multiple myeloma: a VA study. Blood [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 20];133:2615–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(260)Williams CD, Salama JK, Moghanaki D, Karas TZ, Kelley MJ. Impact of Race on Treatment and Survival among U.S. Veterans with Early-Stage Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol [Internet]. Elsevier; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];11:1672–81.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(261)Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, Vitzthum LK, Deka R, Sarkar RR, et al. Survival of African American and non‐Hispanic white men with prostate cancer in an equal‐access health care system. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 27];cncr.32666.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Disparities in Treatment with Surgery

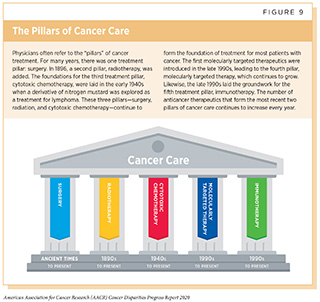

For many decades, surgery was the only pillar of cancer treatment (see Figure 9). Today, it remains the foundation of treatment for many patients with cancer, including patients with breast cancer, such as Shirley Dilbert, and patients with colorectal cancer, which are two cancer types for which there are survival and overall death rate disparities experienced by racial and ethnic minorities. For cancer types associated with high mortality, such as lung and pancreatic cancer, surgical resection is a key to survival when these tumors are detected at an early stage. For other types of cancer, specialty surgical services are necessary to optimize quality of life after treatment, such as reconstruction surgery for breast cancer patients requiring mastectomy and sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer patients.

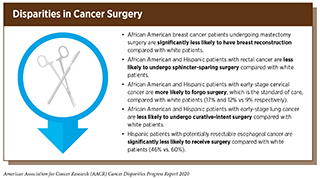

Unfortunately, racial and ethnic minorities often experience disparities in surgical management of cancer (see sidebar on Disparities in Cancer Surgery). These disparities are seen across cancer types and for a variety of reasons. For example, socioeconomic disadvantages that are more prevalent in racial and ethnic minority patients such as African Americans and Hispanics can result in diagnostic delays that render these patients less likely to be candidates for curative cancer surgery (262)Molina Y, Silva A, Rauscher GH. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Time to a Breast Cancer Diagnosis: The Mediating Effects of Health Care Facility Factors. Med Care [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];53:872–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(263)George P, Chandwani S, Gabel M, Ambrosone CB, Rhoads G, Bandera E V, et al. Diagnosis and surgical delays in African American and white women with early-stage breast cancer. J Womens Health (Larchmt) [Internet]. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];24:209–17.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Racial/ethnic minority patients are also more likely to receive their cancer care in safety net and public hospitals, which are less likely to have surgical oncology programs that can support complex cancer perioperative needs compared with other hospitals and specialty cancer centers (264)Keating NL, Kouri EM, He Y, Freedman RA, Volya R, Zaslavsky AM. Location Isn’t Everything: Proximity, Hospital Characteristics, Choice of Hospital, and Disparities for Breast Cancer Surgery Patients. Health Serv Res [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111); 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];51:1561–83.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Implicit bias and unconscious discriminatory practices on the part of health care providers can also have an adverse effect on communication regarding disease management (265)Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, Albrecht TL, Chapman R, Foster T, et al. The Effects of Oncologist Implicit Racial Bias in Racially Discordant Oncology Interactions. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 22];34:2874–80.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(266)Liang J, Wolsiefer K, Zestcott CA, Chase D, Stone J. Implicit bias toward cervical cancer: Provider and training differences. Gynecol Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 22];153:80–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The inequities that exist in the receipt of guideline-recommended surgery for racial and ethnic minority patients mandate that all stakeholders work together to improve effective communication and access to health care resources that are important for patients while continuing further research into the mechanisms that perpetuate these disparities. The importance of access to high-quality surgical oncology in efforts to achieve cancer health equity is highlighted by studies showing that if African American and white patients who have colon cancer or early-stage lung cancer are treated with surgery through the equal access Veterans Affairs health care system there are no disparities in survival between African Americans and whites (260)Williams CD, Salama JK, Moghanaki D, Karas TZ, Kelley MJ. Impact of Race on Treatment and Survival among U.S. Veterans with Early-Stage Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol [Internet]. Elsevier; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];11:1672–81.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(271)Robinson CN, Balentine CJ, Marshall CL, Anaya DA, Artinyan A, Awad SA, et al. Ethnic disparities are reduced in VA colon cancer patients. Am J Surg [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2019 Dec 17];200:636–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These data stand in stark contrast to overall U.S. data showing that there are significant African American–white disparities in survival from colon cancer and early-stage lung cancer (272)Esnaola NF, Ford ME. Racial differences and disparities in cancer care and outcomes: where’s the rub? Surg Oncol Clin N Am [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 17];21:417–37, viii.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Disparities in Treatment with Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy became the second pillar of cancer treatment in 1896 (see Figure 9). Currently, about 50 percent of patients diagnosed with cancer have radiotherapy to shrink or eliminate tumors or to prevent local recurrence (273)National Academies of Science, Engineering and M. Appropriate use of advanced technologies for radiation therapy and surgery in oncology: Workshop summary.[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see sidebar on Using Radiation in Cancer Care).

Unfortunately, racial and ethnic minorities often experience disparities in treatment with radiotherapy. These disparities are seen across cancer types, including the three most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States—breast, lung, and prostate cancer (34)American Cancer Society. Facts & Figures 2019. Am Cancer Soc Atlanta, Ga. 2019;[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Radiotherapy is an important part of curing breast cancer, in addition to surgery and chemotherapy. For women with early-stage disease that has not spread outside the breast, delivering radiotherapy to the breast after surgery decreases the risk of breast cancer recurring. Radiotherapy is also important for more advanced stages of disease, when the cancer has spread outside of the breast. Research shows that racial and ethnic minority women with breast cancer are less likely to receive radiotherapy, which may contribute to a higher risk of dying from breast cancer. Compared with white women, African American women with early-stage breast cancer are half as likely to be treated with radiotherapy (274)Mandelblatt JS, Kerner JF, Hadley J, Hwang Y-T, Eggert L, Johnson LE, et al. Variations in breast carcinoma treatment in older medicare beneficiaries. Cancer [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2019 Dec 17];95:1401–14.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. African American and Hispanic women with breast cancer are also more likely to experience delays in beginning radiotherapy compared with white women (275)Freedman RA, He Y, Winer EP, Keating NL. Racial/Ethnic differences in receipt of timely adjuvant therapy for older women with breast cancer: are delays influenced by the hospitals where patients obtain surgical care? Health Serv Res [Internet]. Health Research & Educational Trust; 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 17];48:1669–83.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Radiotherapy is part of the treatment for many patients with prostate cancer. Research has shown that among African American men with prostate cancer who receive radiotherapy overall survival is just as good as, if not better than, it is among their white counterparts (276)Kodiyan J, Ashamalla M, Guirguis A, Ashamalla H. Improved Outcomes with Radiation Therapy in African Americans with Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol [Internet]. Elsevier; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];105:E287.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, African American men with prostate cancer are less likely to receive radiotherapy compared to white men (277)Fang P, He W, Gomez D, Hoffman KE, Smith BD, Giordano SH, et al. Racial disparities in guideline-concordant cancer care and mortality in the United States. Adv Radiat Oncol [Internet]. Elsevier; 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 22];3:221–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Moreover, African American men with prostate cancer experience a longer time from diagnosis to the start of radiotherapy compared with white men (278)Stokes WA, Hendrix LH, Royce TJ, Allen IM, Godley PA, Wang AZ, et al. Racial differences in time from prostate cancer diagnosis to treatment initiation. Cancer [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 17];119:2486–93.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition, they are less likely to receive treatment with the intent of cure even when presenting with similar disease stage (279)Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Ziehr DR, Hyatt AS, Sammon JD, Schmid M, et al. Trends in disparate treatment of African American men with localized prostate cancer across National Comprehensive Cancer Network risk groups. Urology [Internet]. Elsevier; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 17];84:386–92.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. These differences were present to a similar extent in both academic and community hospitals (280)Mahal BA, Chen Y-W, Muralidhar V, Mahal AR, Choueiri TK, Hoffman KE, et al. National sociodemographic disparities in the treatment of high-risk prostate cancer: Do academic cancer centers perform better than community cancer centers? Cancer [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 22];122:3371–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Radiotherapy can be used to cure early-stage lung cancer and is used in combination with chemotherapy with or without surgery in the treatment of advanced-stage lung cancer. Unfortunately, African American lung cancer patients are 42 percent less likely to receive radiotherapy compared with their white counterparts (281)Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Given CW. Treatment and survival differences in older Medicare patients with lung cancer as compared with those who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 17];26:5067–73.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Inequities in cancer radiotherapy must be addressed as part of the current efforts to eradicate cancer health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities. Many efforts are underway to understand why these inequities exist and some have provided useful insights into this issue. For example, patient populations that are over-represented among the socioeconomically disadvantaged, such as African Americans and Hispanics, are more likely to rely on public transportation, and so disruptions or delays in service will impact their ability to attend daily radiotherapy. Continued research is needed to better understand the current barriers to the receipt of guideline-concordant radiation therapy for racial and ethnic minorities and to implement effective interventions to address those barriers.

Disparities in Therapeutic Cancer Clinical Trials

Before a candidate anticancer therapeutic can be used as part of patient care, its safety and efficacy must be rigorously tested in clinical trials. All clinical trials are reviewed and approved by an independent committee known as the institutional review board before they can begin and are monitored throughout their duration. If, after reviewing the clinical trial data, the FDA deems the therapeutic safe and effective it is approved for use and will enter clinical practice.

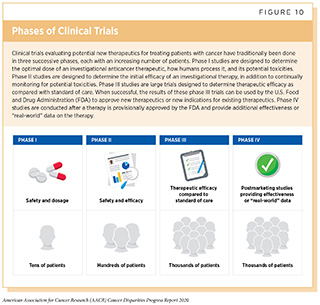

Clinical trials testing candidate therapeutics for patients with cancer have traditionally been done in three successive phases (see Figure 10). The multiphase clinical testing process requires many patients and takes many years to complete.

Lack of Diversity among Clinical Trial Participants

To ensure that candidate anticancer therapeutics are safe and effective for everyone who will use them if they are approved, it is vital that the participants in the clinical trials testing the agents represent the entire population that may use them. Clinical trials also provide cancer patients the opportunity to receive the newest available treatments; therefore, access to clinical trials should be equitable for all patients. Despite this knowledge, low participation in clinical trials and lack of diversity among those who participate are some of the most pressing challenges in clinical research. It is well documented that racial and ethnic minorities are significantly underrepresented in clinical trials relative to their respective cancer burden in the United States (223)American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Cancer Disparities: A Chartbook. Strategies [Internet]. 2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(257)Duma N, Vera Aguilera J, Paludo J, Haddox CL, Gonzalez Velez M, Wang Y, et al. Representation of Minorities and Women in Oncology Clinical Trials: Review of the Past 14 Years. J Oncol Pract [Internet]. 2017;14:JOP.2017.025288.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, 13 percent of the U.S. population is African American and African American men are more than twice as likely to die from prostate cancer (12)DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 15];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. However, fewer than 10 percent of participants in the clinical trials that led to the FDA approvals of apalutamide and darolutamide, two recent new treatments for prostate cancer, were African American (282)New Drugs at FDA: CDER’s New Molecular Entities and New Therapeutic Biological Products | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 17].[cited 2020 Jul 15]. (see Figure 11).

Recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities in cancer clinical trials based on disease incidence rather than their proportion in the general population will allow researchers to obtain a deeper understanding of the biological determinants of cancer outcomes that may be enriched in one racial or ethnic group or another, but not exclusively so. In studying a proportionately appropriate racially and ethnically diverse population we can understand the genetic, epigenetic, metabolomic, and proteomic factors that correspond with response to therapy, regardless of race.

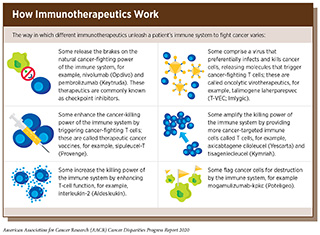

Identifying the subset of patients whose cancers are most likely to respond to immunotherapeutics, which are innovative new treatments for many types of cancer, is a pressing challenge in cancer care. Immunotherapeutics work by unleashing the power of a patient’s immune system to fight his or her cancer, but only about 30 percent of cancers respond to these treatments. Since the ability of tumors to provoke an immune response in the body can differ by racial ancestry, it follows that the inadequate representation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials is a missed opportunity to develop predictive biomarkers to identify responders across more diverse patient populations. Notably, racial and ethnic minority enrollment in pivotal clinical trials leading to FDA approval of immunotherapeutics called immune checkpoint inhibitors is exceedingly low (258)Nazha B, Mishra M, Pentz R, Owonikoko TK. Enrollment of Racial Minorities in Clinical Trials: Old Problem Assumes New Urgency in the Age of Immunotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ book Am Soc Clin Oncol Annu Meet [Internet]. American Society of Clinical OncologyAlexandria, VA; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];39:3–10.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

How Can We Overcome the Current Barriers to Trial Participation?

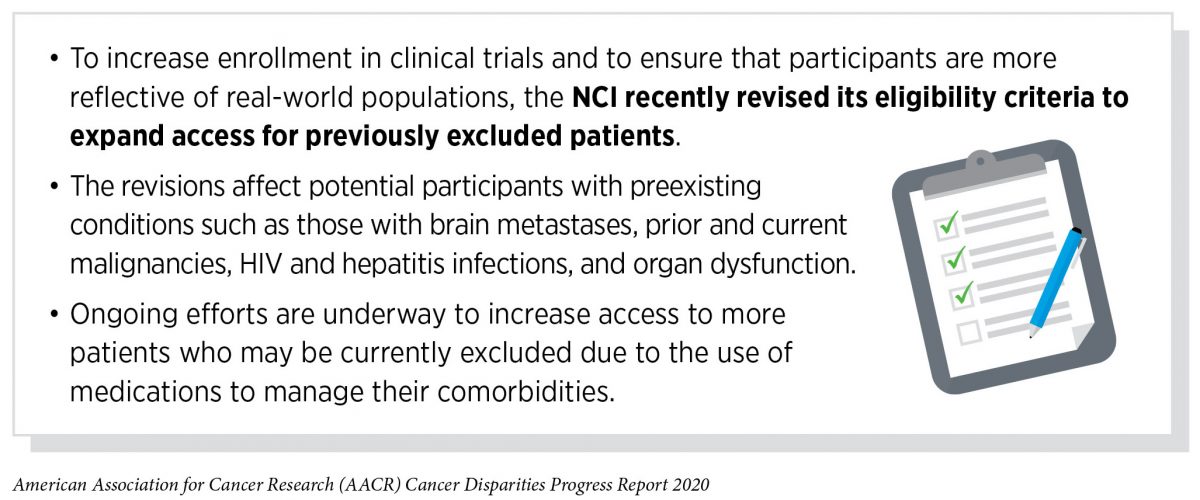

While much work has been done to identify the numerous barriers to cancer clinical trial participation, rates of trial participation for racial and ethnic minorities have not changed substantially over time (257)Duma N, Vera Aguilera J, Paludo J, Haddox CL, Gonzalez Velez M, Wang Y, et al. Representation of Minorities and Women in Oncology Clinical Trials: Review of the Past 14 Years. J Oncol Pract [Internet]. 2017;14:JOP.2017.025288.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Some of the critical issues that have been identified through these studies include structural barriers such as trial availability, clinical barriers such as restrictive eligibility criteria, logistical barriers such as having to take time off work and needing to find and pay for transportation to and from the research site, and patient/physician-related factors including socioeconomic and cultural issues (284)Unger JM, Vaidya R, Hershman DL, Minasian LM, Fleury ME. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Magnitude of Structural, Clinical, and Physician and Patient Barriers to Cancer Clinical Trial Participation. 2019;111:1–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

While certain barriers to clinical trial participation may be difficult to tackle, some could be addressed immediately. The first would be to conduct clinical trials at facilities that treat a high percentage of racial and ethnic minority patients. Many phase III trials are conducted outside the United States, and those within the United States are often limited to the high-volume cancer centers where minority patients are underrepresented (285)Kanapuru B, Singh H, Fashoyin-Aje LA, Myers A, Kim G, Farrell A, et al. FDA analysis of patient enrollment by region in clinical trials for approved oncological indications. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 17];35:2539–2539.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Notably, nearly 85 percent of cancer patients are treated in the community, compared with only about 15 percent in larger, academic centers. It is, therefore, crucial that these studies are available to minority communities. To encourage patients to participate, the clinical research team needs to reach out and work with minority patient populations. For example, the NCI’s Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) is successfully bringing cancer clinical trials into diverse community settings (286)Copur MS, Gulzow M, Zhou Y, Einspahr S, Scott J, Murphy L, et al. Impact of National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP) and NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) on clinical trial (CT) activities in a community cancer center. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];36:e18500–e18500.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Another strategy to diversify clinical trial participants would be to simplify and expand eligibility criteria that often lead to exclusion of racial and ethnic minority patients. These criteria need to keep up with scientific innovation, be pragmatic, and allow flexibility for patients with medical or physical limitations other than their cancer. If candidate anticancer therapeutics are to be given to a broad range of patients once approved, they should be tested in a broad range of patients including those who may have coexisting medical conditions. Furthermore, clinical trials should include collection of real-world data and evidence in the form of patient-reported outcomes, to help us better understand the patient experience from diverse populations.

Increasing diversity among clinical trial participants is perhaps the most important aspect to understanding racial and ethnic differences in treatment outcomes but the effort to mitigate disparities in treatment should not begin or end there, as highlighted by Karen Peterson who participated in a combination immunotherapy trial in 2017. Researchers need to increase minority participation in biobanking, tumor repositories, and genomic analyses, as well as to increase the racial and ethnic diversity of the model systems used to study cancer in order to begin to frame and predict possible effects of genetic and genomic diversity on treatment outcome. To diversify tissue and blood biorepositories we must overcome educational gaps in awareness of the importance of biobanking and participating in clinical research through culturally appropriate and culturally sensitive community-facing education programs that engage and educate diverse populations, neighborhood by neighborhood. In addition, we need continued development of training programs to better enable health care professionals to overcome implicit bias.

Disparities in Treatment with Systemic Therapeutics

Systemic therapy is defined as treatment using therapeutics that travel through the bloodstream, reaching and affecting cells all over the body. Systemic therapeutics for cancer comprise three of the five pillars of cancer care, cytotoxic chemotherapeutics, molecularly targeted therapeutics, and immunotherapeutics (see Figure 9). These treatments can transform lives by improving survival and quality of life for cancer patients, as illustrated by the experience of Fernando Whitehead, who received a cutting-edge immunotherapeutic. However, not all patients receive the treatments recommended for the type and stage of cancer that they have been diagnosed with. Therefore, it is imperative that all stakeholders committed to driving progress against cancer work together to address the challenge of disparities in cancer treatment with systemic therapeutics because these disparities are associated with serious adverse differences in survival.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy became the third pillar of cancer care in the early 1940s. While it remains the foundation of treatment for many cancers, researchers are also constantly developing newer and more sophisticated cytotoxic chemotherapeutics and identifying new ways to use existing cytotoxic chemotherapeutics to improve survival and quality of life for patients. Unfortunately, many reports have documented that African American and Hispanic patients are less likely to receive recommended cytotoxic chemotherapy treatments compared with whites. For example, African American patients with colorectal cancer have been shown to be significantly less likely to be treated with cytotoxic chemotherapeutics compared with white patients and both Hispanic and African American patients with stomach cancer have been shown to be significantly less likely to receive presurgery cytotoxic chemotherapy compared with non-Hispanic whites (21)Lai Y, Wang C, Civan JM, Palazzo JP, Ye Z, Hyslop T, et al. Effects of Cancer Stage and Treatment Differences on Racial Disparities in Survival From Colon Cancer: A United States Population-Based Study. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 11];150:1135–46.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(289)Ikoma N, Cormier JN, Feig B, Du XL, Yamal J-M, Hofstetter W, et al. Racial disparities in preoperative chemotherapy use in gastric cancer patients in the United States: Analysis of the National Cancer Data Base, 2006-2014. Cancer [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];124:998–1007.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Systemic therapeutics directed to the molecules influencing cancer cell multiplication and survival target the cells within a tumor more precisely than cytotoxic chemotherapeutics, which target all rapidly dividing cells, thereby limiting damage to healthy tissues. The greater precision of these molecularly targeted therapeutics tends to make them more effective and less toxic than cytotoxic chemotherapeutics. Molecularly targeted therapeutics have become the fourth pillar of cancer care and are not only saving the lives of patients with cancer, but also allowing these individuals to have a higher quality of life. The effective use of molecularly targeted therapeutics often requires tests called companion diagnostics. Companion diagnostics detect specific molecular abnormalities in cancers to accurately match patients with the corresponding targeted therapy. This allows patients to receive a treatment to which they are most likely to respond, while allowing patients identified as very unlikely to respond to forgo treatment and thus be spared any adverse side effects. The use of molecularly targeted therapeutics has ushered in a new era of precision medicine in which patients are treated based on their particular disease characteristics.

Unfortunately, many recent reports have highlighted that there are striking disparities in the utilization of molecularly targeted treatments among racial and ethnic minority patients. For example, among women with stage III HER2-positive breast cancer, only 56 percent of African American patients received the HER-targeted therapeutic trastuzumab (Herceptin) compared with 74 percent of whites (290)Reeder-Hayes K, Peacock Hinton S, Meng K, Carey LA, Dusetzina SB. Disparities in Use of Human Epidermal Growth Hormone Receptor 2-Targeted Therapy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];34:2003–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. African American patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), were less likely to be tested to determine whether their cancer was fueled by a mutation in the EGFR gene compared with white patients and were less likely to be treated with the EGFR-targeted therapeutic erlotinib (Tarceva) (291)Palazzo LL, Sheehan DF, Tramontano AC, Kong CY. Disparities and Trends in Genetic Testing and Erlotinib Treatment among Metastatic Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];28:926–34.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The disparities in the receipt of these highly effective therapies mandates further research to identify current barriers to the use of molecularly targeted therapeutics among racial and ethnic minority patients.

Cancer immunotherapeutics work by unleashing the power of a patient’s immune system to fight cancer the way it fights pathogens like the virus that causes flu and the bacterium that causes strep throat. There are many ways by which immunotherapeutics can eliminate cancer (see sidebar on How Immunotherapeutics Work). In recent years, it has emerged as the fifth pillar of cancer care and as one the most exciting new approaches to cancer treatment. This is, in part, because many patients with metastatic cancer who have been treated with these revolutionary treatments have had remarkable and durable responses. For example, recent long-term results from a clinical trial testing the immunotherapeutic pembrolizumab (Keytruda) as an initial treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC showed that 23 percent lived five or more years, which stands in stark contrast to the historical five-year relative survival rate of about 5 percent (292)Garon EB, Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, Carcereny E, Leighl NB, Ahn M-J, et al. Five-Year Overall Survival for Patients With Advanced Non‒Small-Cell Lung Cancer Treated With Pembrolizumab: Results From the Phase I KEYNOTE-001 Study. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jul 15];JCO1900934.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

There are, however, confounding data on whether there are racial and ethnic disparities in the use of immunotherapeutics. For example, one study reported disparities in the use of immunotherapeutics based on health insurance status but not race, in patients with advanced melanoma, while a second report highlighted racial and socioeconomic disparities, with African American NSCLC patients consistently less likely to receive immunotherapeutics compared with whites (293)Al-Qurayshi Z, Crowther JE, Hamner JB, Ducoin C, Killackey MT, Kandil E. Disparities of Immunotherapy Utilization in Patients with Stage III Cutaneous Melanoma: A National Perspective. Anticancer Res [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];38:2897–901.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(294)Verma V, Haque W, Cushman TR, Lin C, Simone CB, Chang JY, et al. Racial and Insurance-related Disparities in Delivery of Immunotherapy-type Compounds in the United States. J Immunother [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];42:55–64.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Given these conflicting reports as well as ongoing concerns about racial disparities in access to clinical trials of novel cancer drugs, including immunotherapeutics, it is critical that ongoing research continue to evaluate the effectiveness and utilization rates of these therapeutics among minority patients in real-world practice.

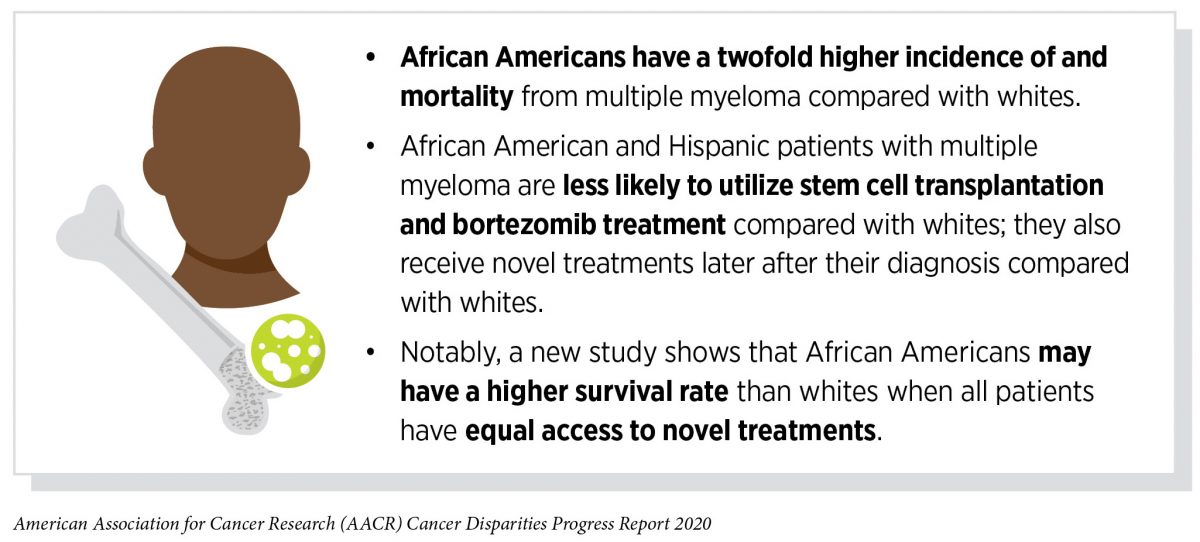

Achieving Equity in Quality Cancer Care

Mounting evidence suggests that for many cancers, racial and ethnic minorities may respond better to treatments and have similar or better outcomes compared to white patients when offered similar access to quality clinical care. Four independent clinical studies in prostate cancer all indicated that although African American men entered into the trials with more advanced disease, they responded better to different types of treatment—cellular immunotherapy, hormone therapy, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy—with a 20 to 30 percent improvement in survival compared with white patients (276)Kodiyan J, Ashamalla M, Guirguis A, Ashamalla H. Improved Outcomes with Radiation Therapy in African Americans with Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol [Internet]. Elsevier; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];105:E287.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(295)Halabi S, Dutta S, Tangen CM, Rosenthal M, Petrylak DP, Thompson IM, et al. Overall Survival of Black and White Men With Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Treated With Docetaxel. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];37:403–10.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(296)Sartor AO, Armstrong AJ, Ahaghotu C, McLeod DG, Cooperberg MR, Penson DF, et al. Overall survival (OS) of African-American (AA) and Caucasian (CAU) men who received sipuleucel-T for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Final PROCEED analysis. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];37:5035–5035.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(297)George DJ, Heath EI, Sartor AO, Sonpavde G, Berry WR, Healy P, et al. Abi Race: A prospective, multicenter study of black (B) and white (W) patients (pts) with metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) treated with abiraterone acetate and prednisone (AAP). J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];36:LBA5009–LBA5009.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, a survival analysis of African American versus white men with prostate cancer treated with the cellular immunotherapeutic sipuleucel-T (Provenge) showed that the median overall survival was 37.3 months among the African Americans compared with 28 months among the white patients. Similar trends were also reported in a study from the Veterans Administration health care system, where overall use of new treatments, such as the immunomodulatory drugs and proteasome inhibitors that Alfred Johnson was treated with, was the same across all multiple myeloma patient populations. The researchers showed that younger African American patients had better survival than whites. Specifically, the median overall survival for patients under 65 was significantly better (7.07 years) for African Americans compared with whites (5.83 years) (259)Fillmore NR, Yellapragada S V, Ifeorah C, Mehta A, Cirstea D, White PS, et al. With equal access, African American patients have superior survival compared to white patients with multiple myeloma: a VA study. Blood [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 20];133:2615–8.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Given the emerging evidence that disparities in outcomes can often be mitigated when patients from racial and ethnic minority groups receive the same treatments, it is important that researchers devise innovative strategies, including novel clinical trial designs, to ensure that all patients receive standard treatments and participate in cutting-edge clinical trials. These new strategies must simultaneously address more than one of the many complex and interrelated factors contributing to disparities in treatment. Multilevel interventions, including improved use of real-time signals from electronic health records, intensive training in overcoming implicit bias, and implementation of patient navigation programs, can improve delivery of guideline-concordant care, help patients overcome barriers to care, improve participation in clinical trials, and mitigate disparities in therapy (298)Cykert S, Eng E, Walker P, Manning MA, Robertson LB, Arya R, et al. A system‐based intervention to reduce Black‐White disparities in the treatment of early stage lung cancer: A pragmatic trial at five cancer centers. Cancer Med [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18];8:1095–102.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(299)Cykert S, Eng E, Manning MA, Robertson LB, Heron DE, Jones NS, et al. A Multi-faceted Intervention Aimed at Black-White Disparities in the Treatment of Early Stage Cancers: The ACCURE Pragmatic Quality Improvement trial. J Natl Med Assoc [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18];[cited 2020 Jul 15].(300)Hu B. Minorities Do Not Have Worse Outcomes for Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) If Optimally Managed [Internet]. ASH; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, a recent clinical study conducted across five U.S. cancer centers showed that a multipronged intervention that included nurse navigators, a real-time warning system using data from electronic health records to alert nurse navigators if patients miss an appointment or do not reach an expected care milestone, and race-specific feedback to clinical teams on treatment completion rates was not only able to eliminate treatment disparities among African American and white patients with early-stage lung cancer, but also improved care for all patients regardless of race (298)Cykert S, Eng E, Walker P, Manning MA, Robertson LB, Arya R, et al. A system‐based intervention to reduce Black‐White disparities in the treatment of early stage lung cancer: A pragmatic trial at five cancer centers. Cancer Med [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18];8:1095–102.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The importance of nurse navigators was highlighted in another recent study showing that African American and Hispanic patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma were just as likely as white patients to receive standard treatments and participate in clinical trials at a safety net hospital that has an extensive nurse navigator program to help disadvantaged patients access and complete treatment by guiding them through treatment, helping them with lodging, and providing other nonmedical support (300)Hu B. Minorities Do Not Have Worse Outcomes for Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) If Optimally Managed [Internet]. ASH; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Whether similar multifaceted interventions could be implemented widely across multiple health care systems, for different cancer types, and whether they can be effective in achieving health equity for all must be evaluated. However, these findings strongly support the importance of conducting innovative translational and clinical cancer research to determine how to eliminate disparities in cancer treatment and improve outcomes in diverse populations.

Moving forward, we need to ensure that everyone benefits from breakthroughs against cancer. Cancer researchers must move past simply describing disparities to developing a more in-depth understanding of the interrelated factors that are associated with disparate cancer treatments and outcomes. A greater understanding of the underlying factors will lay the foundation for comprehensive, sustainable, population-level interventions than can potentially narrow treatment differences among different populations and improve outcomes for all patients. Furthermore, all scientific endeavors must be complemented with evidence-based policy initiatives that aim toward delivering guideline-concordant quality care for every cancer patient. It is imperative that all stakeholders committed to fundamentally changing the face of cancer work together to address the challenges of disparities in cancer treatment and lead us toward a brighter future with health equity for all Americans.