Preventing Cancer: Identifying Risk Factors

In this section, you will learn:

- In the United States, four out of 10 cancer cases and almost half of all cancer-related deaths are associated with preventable risk factors.

- Not using tobacco is the single best way a person can prevent cancer from developing.

- Nearly 20 percent of U.S. cancer diagnoses are related to excess body weight, alcohol intake, poor diet, and physical inactivity.

- Many cases of skin cancer could be prevented by protecting the skin from ultraviolet radiation from the sun and indoor tanning devices.

- Nearly all cases of cervical cancer could be prevented by HPV vaccination, but 49 percent of U.S. adolescents have not received the recommended doses of the vaccine.

In the United States, the overall cancer death rate has been declining steadily over the past two decades, and the number of individuals living with a history of cancer has reached a record high. However, even in 2019, an estimated 606,880 people will die from cancer. Nearly half of these deaths will be attributable to cancers caused by potentially modifiable risk factors (46).

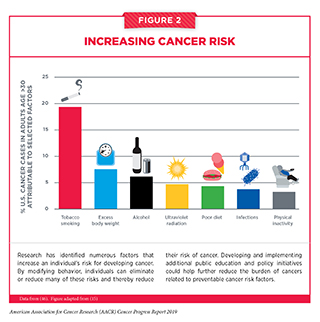

Thanks to decades of research, we have identified several factors that increase a person’s risk of developing and/or dying from cancer, including cigarette smoking, excess body weight, unhealthy diet, exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and infection with certain pathogens (see Figure 2). In fact, 40 percent of the cancer cases diagnosed in the United States in 2014 were caused by potentially modifiable risk factors (46). Given that several of these risk factors can be avoided, many cases of cancer could potentially be prevented. Many of the same risk factors are also associated with worse outcomes after a cancer diagnosis. Therefore, lifestyle modifications such as quitting smoking and increasing physical activity can improve health outcomes in cancer patients and survivors (see Promoting Healthy Behaviors).

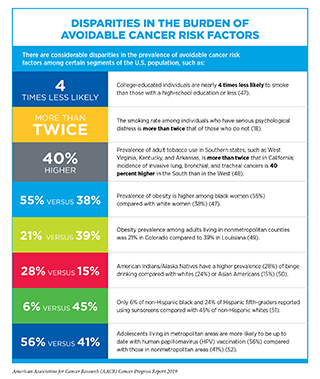

The development and implementation of public education and policy initiatives designed to eliminate or reduce exposure to preventable causes of cancer have reduced cancer morbidity and mortality in the United States. For example, tobacco control efforts implemented since the 1960s have led to considerable reductions in smoking and smoking-related diseases, including lung cancer. Despite these measures, the prevalence of some of the major cancer risk factors continues to be high (47), particularly among segments of the U.S. population that experience cancer health disparities, such as racial and ethnic minorities, individuals from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and those with lower educational attainment (see sidebar on Disparities in the Burden of Avoidable Cancer Risk Factors). Thus, we must identify more effective strategies for disseminating our current knowledge of cancer prevention and implement evidence-based interventions to reduce the burden of cancer for everyone.

Eliminate Tobacco Use

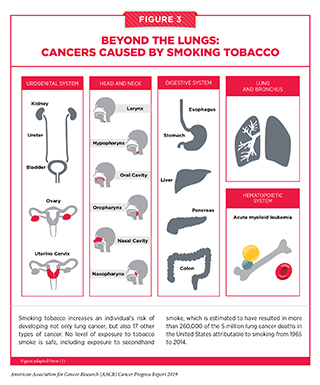

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer because it exposes individuals to many harmful chemicals that damage DNA, causing genetic and epigenetic alterations that lead to cancer development (53–55). Smoking tobacco has been shown to increase the risk of developing 17 different types of cancer in addition to lung cancer (see Figure 3). Fortunately, quitting at any age can reduce these risks. In fact, the health benefits of cessation begin just weeks after quitting, and 10 years after quitting, the risks of all smoking-related cancers are reduced by 50 percent (56) (57). Thus, one of the most effective ways a person can lower his or her risk of developing cancer and other smoking-related conditions, such as cardiovascular, metabolic, and lung diseases, is to avoid or eliminate tobacco use.

Thanks to the implementation of nationwide comprehensive tobacco control initiatives, cigarette smoking among U.S. adults has been declining steadily and reached an all-time low of 14 percent in 2017 – a 67 percent reduction since 1965 (18). Exposure to secondhand smoke, which increases the risk of lung cancer among nonsmokers, has also dropped substantially over the past three decades (58). Consequently, the incidence of tobacco-associated cancers has been declining, and a recent report projects that the number of annual lung cancer deaths will drop by 63 percent within the next 50 years if the smoking rate continues to decrease in the future (48)(59).

Despite these positive trends we cannot overlook the fact that 34 million adults were still smoking cigarettes in 2017 (18). There are also striking sociodemographic disparities in smoking behavior (see sidebar on Disparities in the Burden of Avoidable Cancer Risk Factors). Thus, it is imperative that researchers, advocates, and policy makers continue to work together to identify evidence-based population-level interventions such as tobacco price increases, public health campaigns, age and marketing restrictions, cessation counseling and medications, and smoke-free laws to reduce smoking rates and smoking-related cancer burden in the United States. For instance, based on evidence that nearly 95 percent of adults who smoke report trying their first cigarette before the age of 21, 17 U.S. states have passed legislation to raise the minimum legal sale age for tobacco product to 21. This is a critically important strategy to reduce the burden of tobacco use because a recent report estimated that raising the minimum age for purchase of all tobacco products to 21, nationwide, could prevent 223,000 deaths among people born between 2000 and 2019, including 50,000 fewer deaths from lung cancer (60).

The use of other combustible tobacco products (for example, cigars), smokeless tobacco products (for example, chewing tobacco and snuff), and waterpipes (hookahs) is also associated with adverse health outcomes including cancer (64). Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are a rapidly emerging tobacco product. An alarming trend in recent years has been the growing popularity of e-cigarettes among U.S. youth and young adults. E-cigarettes were first introduced to the U.S. market in 2007 and since 2014 have been the most commonly used tobacco product among U.S. middle- and high-school students (65) (see sidebar on E-Cigarettes: What Have We Learned and What Do We Need to Know?).

The recent surge in e-cigarette use among youth coincides with the growing popularity of JUUL, a brand of e-cigarettes that are shaped like USB flash drives and can be used discreetly in schools or public settings (67). These products come in flavors that appeal to youth and deliver very high levels of nicotine, an extremely addictive substance that is harmful to the developing brain (71). According to recent studies, many users are unfortunately unaware that they are exposed to the same amount of nicotine as tobacco smokers (72)(73). There is also evidence that the use of e-cigarettes may act as a gateway to smoking combustible cigarettes by youth (66)(74). Thus, it is very concerning that the current use of e-cigarettes increased by nearly 80 percent and 50 percent among high-school and middle-school students, respectively, between 2017 and 2018 (68). Evidently, current policies to limit the spread of e-cigarettes among youth have been inadequate.

In the past year, the FDA has proposed several restrictions on e-cigarettes to curb youth access, and in December 2018, the Office of the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory declaring e-cigarette use in youth an epidemic (see Supporting Policies to Reduce The Use of Tobacco Products). It is imperative that all stakeholders continue to work together to determine the long-term health outcomes associated with e-cigarettes and identify new strategies to implement population-level regulations to reduce e-cigarette use among youth and young adults.

Maintain a Healthy Weight, Eat a Healthy Diet, and Stay Active

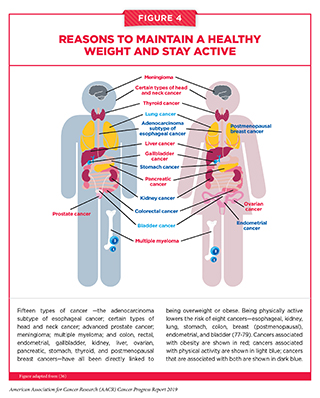

About 20 percent of new cancer cases and 16 percent of cancer deaths in U.S. adults are attributable to a combination of being overweight or obese, poor diet, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol consumption (46). Being overweight or obese as an adult increases a person’s risk for 15 types of cancer. Conversely, being physically active reduces risk for eight types of cancer (see Figure 4). Therefore, maintaining a healthy weight, being physically active, and consuming a balanced diet are effective ways a person can lower his or her risk of developing or dying from cancer (see sidebar on Reduce Your Risk for Cancer by Maintaining a Healthy Weight, Being Physically Active, and Consuming a Balanced Diet). Identifying the ways in which obesity, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity increase cancer risk is an area of active research investigation.

The prevalence of obesity has been rising steadily in the United States and around the globe. According to the latest estimates, nearly 40 percent of adults in the United States are obese (47) while nearly 5 and 10 percent of all cancer cases in men and women, age 30 or older, can be attributed to excess body weight (19). Globally, excess body weight is responsible for about 4 percent of all cancer cases (75). Beyond cancer, obesity increases the risk of developing several other health problems including type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, liver disease, and kidney disease (76).

Complex and interrelated factors ranging from socioeconomic and environmental influences to individual lifestyle factors contribute to obesity. There is, however, sufficient evidence that consumption of high-calorie, energy-dense food and beverages and insufficient physical activity play a significant role (76). In the United States, more than 5 percent of all newly diagnosed cancer cases among adults are attributable to eating a poor diet (80). Low intake of healthy foods such as whole grains, fruits, nuts, and seeds combined with the high intake of unhealthy foods such as sugar-sweetened drinks and high levels of red and processed meats are, in fact, responsible for one in five deaths globally (81).

Intensive efforts by all stakeholders are needed if we are to increase the number of people who consume a balanced diet, such as that recommended by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (82). One initiative that has been effective in lowering the rates of obesity and severe obesity among children is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC) (83). Initiatives such as WIC are extremely important given that obesity during early childhood is associated with sustained overweight or obesity in adolescence and adulthood and that obesity during adolescence can increase the risk of developing cancer later in life (84–86).

Another recent policy approach aimed at reducing obesity is the introduction of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages in several local jurisdictions in the United States (87). Sugar-sweetened beverages are a major contributor to caloric intake among U.S. youth and adults (88-89). Thus, it is encouraging that since the implementation of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages, there are already some indications of reduction in consumption, especially in lower-income, racially and ethnically diverse neighborhoods (90-91). However, ongoing research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of these policies on obesity and obesity-related health outcomes such as cancer.

An estimated 2 percent of cancer deaths in the U.S. can be attributed to physical inactivity. Physical activity can reduce the risk of eight types of cancer (see Figure 4). There is growing evidence that physical fitness may also reduce the risk of developing additional types of cancer (92). Furthermore, physical activity can dramatically lower rates of all-cause mortality after a diagnosis of certain types of cancer (see Supporting Cancer Patients and Survivors). Considering this evidence, it is concerning that 35 percent of U.S. adults are physically inactive, and only a quarter of children and teenagers get the recommended hour of moderate-to-vigorous exercise a day (93)(94)(95). It is imperative that health care professionals and policy makers work together to increase awareness of the benefits of physical activity and support efforts to implement programs and policies to facilitate physical activity for all Americans (see sidebar on Physical Activity Guidelines).

Limit Alcohol Consumption

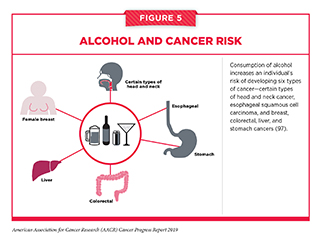

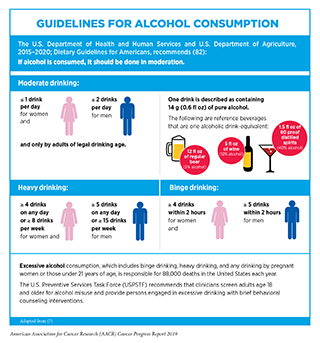

Alcohol consumption has been causally linked with six different types of cancer (97) (see Figure 5). Even modest use of alcohol may increase cancer risk, but the greatest risks are associated with excessive and/or long-term consumption (98-101) (see sidebar on Guidelines for Alcohol Consumption). Thus, it is concerning that in the United States, one in four adults binges on alcohol at least once a month (102). Researchers have identified multiple ways in which alcohol may increase the risk of cancer, including directly damaging cellular DNA and proteins through the production of toxic chemicals, once alcohol is metabolized after drinking (103).

Beyond the United States, alcohol poses a significant public health challenge globally. In fact, alcohol-use disorders are now the most prevalent of all substance-use disorders worldwide (104), and in 2016, excessive use of alcohol resulted in 3 million deaths, including an estimated 0.4 million deaths from cancers (105). These data underscore the importance of adherence to comprehensive guidelines and limiting alcohol intake (for those who drink) to minimize the risk of developing a disease or dying due to alcohol. Future efforts focusing on public education and evidence-based policy interventions, such as regulating alcohol retail density, taxes, and prices, need to be implemented along with effective clinical strategies to reduce the burden of cancer related to alcohol abuse.

Protect Skin from UV Exposure

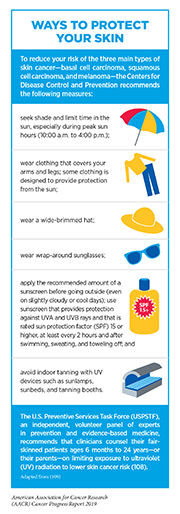

All three main types of skin cancer – basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer – are caused by exposure to UV radiation from the sun or indoor tanning devices. Sunburn, a clear indication of overexposure to UV radiation, is a preventable risk factor for skin cancer and those events occurring in childhood pose some of the greatest risk (107). Therefore, one of the most effective ways a person can reduce his or her risk of skin cancer is by practicing sun-safe habits and not using UV indoor tanning devices (see sidebar on Ways to Protect Your Skin).

In the United States, melanoma incidence among non-Hispanic whites continues to rise, particularly in individuals older than 55 (110). To break the current trend, we need to establish skin cancer prevention as a national priority. In an effort to achieve this goal, the U.S. Surgeon General released a call to action to prevent skin cancer in 2014 (111). Since its release, multiple sectors including health care, government, business, advocacy, and communities have coordinated efforts and made major strides toward reducing exposure. As a result, indoor tanning among U.S. youth and adults has declined significantly (112-113). However, even in 2015, more than 35 percent of adults reported experiencing sunburns either through outdoor exposure or indoor tanning (47). Furthermore, according to a recent survey, even though 68 percent of Americans know that skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States, only 42 percent put sunscreen on parts of their body exposed to the sun (114). Continued efforts from all sectors are necessary to identify and implement more effective interventions to promote sun-safe behavior and reduce the burden of skin cancer.

Prevent and Eliminate Infection with Cancer-causing Pathogens

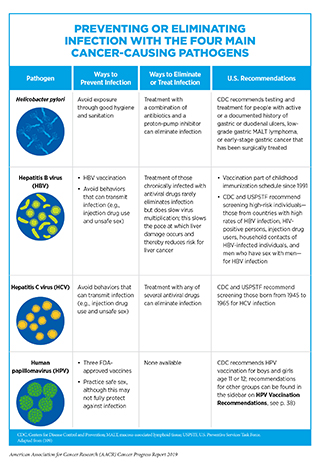

Persistent infection with several pathogens including the human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Helicobacter pylori is known to cause cancer (see Table 3). In the United States, in 2014, about 3 percent of all cancer cases and cancer deaths were attributable to infection with pathogens (46). Individuals, therefore, can significantly lower their risks by protecting themselves from infection or by obtaining treatment, if available, to eliminate an infection (see sidebar on Preventing or Eliminating Infection with the Four Main Cancer-causing Pathogens).

Although there are strategies available to eliminate, treat, or prevent infection with Helicobacter pylori, HBV, HCV, and HPV that can significantly lower an individual’s risks for developing an infection-related cancer, it is important to note that these strategies are not effective at treating infection-related cancers once they develop. It is also clear that these strategies are not being used optimally. For example, even though the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend one-time HCV testing for baby boomers, recent data show that only 14 percent of adults in this population group have been tested (117). Given that in the United States, liver cancer incidence is increasing rapidly and that infection with HBV or HCV accounts for 65 percent of liver cancers, more effective implementation of vaccination, screening, and treatment is needed urgently to significantly reduce the burden of this disease (118). In this regard, a recent initiative that is aimed to reduce the burden of HCV infection is the recommendation from the Indian Health Service for universal screening of all American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) adults. Among AI/AN, HCV infections occur earlier than in the general population and HCV-related deaths are double the national rate (119).

It is estimated that in the United States, HPV infection, accounts for nearly 34,000 cancers each year including almost all cervical and anal cancers as well as the majority of vaginal, vulvar, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers (120). HPV vaccines are highly effective and can prevent up to 90 percent of HPV-related cancers. In fact, since the introduction of HPV vaccines in the United States, the rates of vaccine-targeted cervical HPV infection have declined, and early evidence suggests declines in incidence of cervical precancer and cancer among young females (121-125). Despite the clear effectiveness of HPV vaccines, in 2018, only 54 percent of girls and 49 percent of boys were up to date with the recommended vaccination regimen (52). Although these numbers show slight improvement over earlier years, vaccination rates in the United States are much lower than they are in other developed countries such as Australia where high uptake (above 70 percent) is predicted to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health concern within the next 20 years (126).

Until recently, cervical cancer was the most common HPV-related cancer in the United States. However, the incidence of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer has been increasing, mostly among men, while the incidence of cervical cancer has been declining and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma was recently reported to have become the most common HPV-associated cancer in the United States (121). There are, however, no formal screening tests for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Therefore, developing effective strategies to increase the uptake of HPV vaccines, such as those detailed in the recent report from the U.S. President’s Cancer Panel, could have immense public health benefit (120).

Be Cognizant of Reproductive and Hormonal Influences

Breastfeeding

There is strong evidence that breastfeeding decreases the risk of breast cancer in the mother (128). Women who breastfeed have a lower risk of a particularly aggressive type of breast cancer known as triple-negative breast cancer (129). According to recent data (130), breastfeeding is associated with a 22 percent reduction in the risk of developing triple-negative breast cancer, whereas weaker or no correlations have been observed with other types of breast cancer. Increasing awareness of this information among African American women may be particularly important because African-American women have a disproportionately high incidence of triple-negative breast cancer and a lower prevalence of breastfeeding compared to all other U.S. racial and ethnic groups (131).

Hormone replacement therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) refers to treatments that aim to relieve the common symptoms of menopause and the long-term biological changes, such as bone loss, that occur after menopause due to declining levels of the hormones estrogen and progesterone in a woman’s body. HRT usually involves treatment with estrogen alone or estrogen in combination with progestin, a synthetic hormone like progesterone.

Women who have a uterus are prescribed estrogen plus progestin. This is because estrogen alone, but not in combination with progestin, is associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer, a type of cancer that forms in the tissue lining the uterus. Estrogen alone is used only in women who have had their uteruses removed.

The most comprehensive evidence about the health effects of HRT was obtained from clinical trials conducted by the NIH as part of the Women’s Health Initiative. The data indicated that women who use estrogen plus progestin have an increased risk of developing breast cancer (132). The risk is greater with longer duration of use but decreases significantly following cessation (133). The increased risks have been observed both for white and black women (134-135). Therefore, individuals who are seeking relief from menopausal symptoms should discuss with their health care providers the advantages and possible risks of using HRT before making a decision about what is right for them.

Limit Exposure to Environmental Carcinogens

Environmental exposures to pollutants and occupational agents can increase a person’s risk of cancer. For example, radon, a naturally occurring radioactive gas that comes from the breakdown of uranium in soil, rock, and water, is the second leading cause of lung cancer in the United States (136). Other examples of environmental carcinogens include asbestos, lead, radiation, and benzene. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), environmental risk factors account for nearly 20 percent of all cancers, globally, most of which occur in low- and middle-income countries.

It is often difficult for people to avoid or reduce their exposure to environmental carcinogens, and not every exposure will lead to cancer. The intensity and duration of exposure, combined with an individual’s biological characteristics, including genetic makeup, determine each person’s chances of developing cancer over his or her lifetime. In addition, when studying environmental cancer risk factors, it is important to consider that exposure to several environmental cancer risk factors may occur simultaneously. Growing knowledge of the environmental pollutants to which different segments of the U.S. population are exposed highlights new opportunities for education and policy initiatives to improve public health.

One environmental pollutant that was classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an affiliate of the WHO, as having the ability to cause cancer in humans, is outdoor air pollution (137). Two types of air pollution are most common in the United States, ozone and particle pollution. Particle pollution refers to a mix of tiny solid and liquid particles that are in the air we breathe, and in 2013, IARC concluded that particle pollution may cause lung cancer (138). Therefore, it is concerning that from 2015 to 2017, nearly 20 million people in the United States were exposed year-round to unhealthy levels of particle pollution. New policy efforts to reduce the release of pollutants into the atmosphere are needed if we are to reduce the burden of cancer.

Involuntary exposures to environmental pollutants usually occur in subgroups of the population, such as workers in certain industries who may be exposed to carcinogens on the job or individuals living in low-income neighborhoods. Similarly, there are disparities in the burden of cancers caused by environmental exposures based on geographic locations and socioeconomic status. As we learn more about environmental and occupational cancer risk factors and identify those segments of the U.S. population who are exposed to these factors, we need to develop and implement new and/or more effective policies that benefit everyone, including the most vulnerable and underserved populations.