Disparities in Cancer Survivorship

In this section you will learn:

- A record high number of cancer survivors are living in the United States.

- Each person diagnosed with cancer faces their own unique set of challenges, but one in four survivors report a poor physical quality of life and one in 10 report a poor mental health–related quality of life.

- Racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations shoulder a disproportionate burden of the adverse effects of cancer and cancer treatment, including physical, emotional, psychosocial, and financial challenges.

- An interdisciplinary team science approach to cancer survivorship research that is informed by the voices of community members such as patient advocates will result in improved health care and health status for racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations.

Advances in cancer detection, diagnosis, and treatment are helping more and more people to survive longer and lead fuller lives after a cancer diagnosis. According to the latest estimates, more than 16.9 million U.S. adults and children with a history of cancer were alive on January 1, 2019, compared with just 3 million in 1971, and this number is projected to rise to 22.1 million by January 1, 2030 (301)Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. American Cancer Society; 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 19];caac.21565.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(302)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer Survivorship—United States, 1971–2001. Morbitity Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:526–529.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The increase over the current number of cancer survivors is anticipated largely because the number of people being diagnosed with cancer each year is projected to rise sharply in the coming decades as a result of overall population growth, and because the segment of the U.S. population that accounts for the majority of cancer diagnoses—those age 65 and older (4)Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ CK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. Based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019. [cited 2020 Jul 15].—is expected to grow from 49 million in 2016 to 73 million in 2030 (303)2017 National Population Projections Datasets [Internet]. U.S. Census Bur. Washingt. DC. 2017.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Given that the proportion of individuals age 65 and older who are racial and ethnic minorities is projected to increase markedly, we need to better understand the needs of this population and to identify strategies to overcome the cancer-related challenges faced by this population (304)Vincent G. The next four decades the older population in the United States : 2010 to 2050. 2010;[cited 2020 Jul 15].(305)Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2009 [cited 2019 Dec 17];27:2758–65.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Cancer survivorship encompasses three distinct phases: the time from diagnosis to the end of initial treatment, the transition from initial treatment to extended survival, and long-term survival. Each phase of cancer survivorship is accompanied by a unique set of challenges (see sidebar on Life after a Cancer Diagnosis in the United States). Importantly, the issues facing each cancer survivor vary.

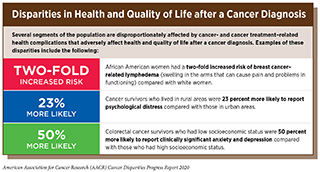

Certain segments of the U.S. population, including racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations, shoulder a disproportionate burden of the adverse effects of cancer and cancer treatment, including physical, emotional, psychosocial, and financial challenges (see sidebar on Disparities in Quality of Life after a Cancer Diagnosis).

Disparities in Long-term and Late Effects of Cancer Treatment

Cancer survivors often face serious and persistent adverse outcomes as a result of the cancer diagnosis and treatment. Many adverse outcomes experienced by cancer survivors begin during cancer treatment and continue in the long term, these are known as long-term effects of treatment. Other adverse outcomes can appear months or even years later; these are known as late effects of treatment.

Current knowledge indicates that there are racial and ethnic disparities in the late and long-term effects of cancer treatments, in particular among women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer (306)Kwan ML, Yao S, Lee VS, Roh JM, Zhu Q, Ergas IJ, et al. Race/ethnicity, genetic ancestry, and breast cancer-related lymphedema in the Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. Netherlands; 2016;159:119–29.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(309)Litvak A, Batukbhai B, Russell SD, Tsai H-L, Rosner GL, Jeter SC, et al. Racial disparities in the rate of cardiotoxicity of HER2-targeted therapies among women with early breast cancer. Cancer [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 19];124:1904–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(310)Bhatnagar B, Gilmore S, Goloubeva O, Pelser C, Medeiros M, Chumsri S, et al. Chemotherapy dose reduction due to chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant settings: a single-center experience. Springerplus [Internet]. Springer; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 17];3:366.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, African American women have been found to have a two-fold increased risk of breast cancer–related lymphedema (swelling in the arms that can cause pain and problems in functioning) compared with white women (306)Kwan ML, Yao S, Lee VS, Roh JM, Zhu Q, Ergas IJ, et al. Race/ethnicity, genetic ancestry, and breast cancer-related lymphedema in the Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. Netherlands; 2016;159:119–29.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition, African American women with breast cancer who were being treated with cytotoxic chemotherapeutics called taxanes were significantly more likely to have chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy leading to a reduction in the dose of chemotherapy they received compared with white women (310)Bhatnagar B, Gilmore S, Goloubeva O, Pelser C, Medeiros M, Chumsri S, et al. Chemotherapy dose reduction due to chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant settings: a single-center experience. Springerplus [Internet]. Springer; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 17];3:366.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Treatment with HER2-targeted therapeutics has also been shown to cause more than twice the rate of heart damage (cardiotoxicity) among African American women with HER2-positive breast cancer compared with white women and therefore African American women had a significantly greater probability of not completing therapy (309)Litvak A, Batukbhai B, Russell SD, Tsai H-L, Rosner GL, Jeter SC, et al. Racial disparities in the rate of cardiotoxicity of HER2-targeted therapies among women with early breast cancer. Cancer [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 19];124:1904–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Survivors of cancer diagnosed during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood (from age 0 to 39), are particularly at risk for severe long-term and late effects. To date, few studies have investigated racial and ethnic disparities in the late and long-term effects of cancer treatments for children, adolescents, and young adults. One study showed that African American adolescents and young adults surviving two or more years after a Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis were 37 percent more likely to have endocrine diseases and 58 percent more likely to have circulatory system diseases than whites (311)Keegan THM, Li Q, Steele A, Alvarez EM, Brunson A, Flowers CR, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in the occurrence of medical conditions among adolescent and young adult Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Cancer Causes Control. Netherlands; 2018;29:551–61.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In the same study, Hispanic adolescents and young adults were 24 percent more likely to have endocrine diseases than whites.

Disparities in Health-related Quality of Life

A cancer diagnosis and treatment for the disease can have a considerable impact on a person’s quality of life. For cancer patients and survivors, health-related quality of life is a multidimensional concept that goes beyond the person’s cancer-related outcomes and considers the impact of cancer and cancer treatments on the person’s overall physical, functional, psychological, social, and financial well-being (312)Ashing-Giwa KT. The contextual model of HRQoL: A paradigm for expanding the HRQoL framework. Qual Life Res [Internet]. Springer; 2005 [cited 2019 Dec 17];14:297–307.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(313)Barile JP, Reeve BB, Smith AW, Zack MM, Mitchell SA, Kobau R, et al. Monitoring population health for Healthy People 2020: evaluation of the NIH PROMIS® Global Health, CDC Healthy Days, and satisfaction with life instruments. Qual Life Res [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 17];22:1201–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Health-related quality of life is often measured using patient-reported, subjective evaluations. Overall, cancer survivors report lower general health and quality of life compared with people without a history of cancer (314)Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, Alfano CM, Rodriguez JL, Sabatino SA, et al. Mental and Physical Health-Related Quality of Life among U.S. Cancer Survivors: Population Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 17];21:2108–17.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(315)Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2019 Dec 17];58:82–91.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(316)Williams K, Jackson SE, Beeken RJ, Steptoe A, Wardle J. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on health and well-being: a prospective, population-based study. Psychooncology [Internet]. Wiley-Blackwell; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];25:626–32.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, in one study, 25 percent of cancer survivors reported a poor physical quality of life and 10 percent reported a poor mental health–related quality of life compared with 10 percent and 6 percent of people without a history of cancer, respectively (314)Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, Alfano CM, Rodriguez JL, Sabatino SA, et al. Mental and Physical Health-Related Quality of Life among U.S. Cancer Survivors: Population Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 17];21:2108–17.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Several studies have shown that racial and ethnic minorities experience disparities in many measures of health-related quality of life after a cancer diagnosis, during cancer treatment, and after cancer treatment is completed (317)Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla G V., Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res [Internet]. Springer; 2007 [cited 2019 Dec 17];16:413–28.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(318)Hao Y, Landrine H, Smith T, Kaw C, Corral I, Stein K. Residential segregation and disparities in health-related quality of life among Black and White cancer survivors. Heal Psychol [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:137–44.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(319)Ye J, Shim R, Garrett SL, Daniels E. Health-related quality of life in elderly black and white patients with cancer: results from Medicare managed care population. Ethn Dis [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 17];22:302–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(320)Pinheiro LC, Samuel CA, Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Olshan AF, Reeve BB. Understanding racial differences in health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];159:535–43.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(321)Samuel CA, Pinheiro LC, Reeder-Hayes KE, Walker JS, Corbie-Smith G, Fashaw SA, et al. To be young, Black, and living with breast cancer: a systematic review of health-related quality of life in young Black breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. Springer; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];160:1–15.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(322)Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. Springer; 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 17];5:191–207.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(323)Beebe-Dimmer JL, Albrecht TL, Baird TE, Ruterbusch JJ, Hastert T, Harper FWK, et al. The Detroit Research on Cancer Survivors (ROCS) Pilot Study: A focus on outcomes after cancer in a racially-diverse patient population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 17];28:cebp.0123.2018.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, African American cancer patients report significantly lower mental-health quality of life, general health, and social functioning compared with white cancer patients (319)Ye J, Shim R, Garrett SL, Daniels E. Health-related quality of life in elderly black and white patients with cancer: results from Medicare managed care population. Ethn Dis [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2012 [cited 2019 Dec 17];22:302–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among breast cancer survivors, Hispanic women report lower physical, mental health–related, and social health–related quality of life than women of any other racial or ethnic group (322)Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. Springer; 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 17];5:191–207.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The disparities in health-related quality of life are often a result of factors such as age at diagnosis, cancer stage at diagnosis, treatment type, as well as social, clinical, and environmental factors such as income, health insurance status, employment status, and education (317)Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla G V., Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res [Internet]. Springer; 2007 [cited 2019 Dec 17];16:413–28.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(320)Pinheiro LC, Samuel CA, Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Olshan AF, Reeve BB. Understanding racial differences in health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];159:535–43.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(318)Hao Y, Landrine H, Smith T, Kaw C, Corral I, Stein K. Residential segregation and disparities in health-related quality of life among Black and White cancer survivors. Heal Psychol [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:137–44.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(324)Hastert TA, Kyko JM, Reed AR, Harper FWK, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Baird TE, et al. Financial Hardship and Quality of Life among African American and White Cancer Survivors: The Role of Limiting Care Due to Cost. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];28:1202–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(325)Miller AM, Ashing KT, Modeste NN, Herring RP, Sealy D-AT. Contextual factors influencing health-related quality of life in African American and Latina breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];9:441–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Even though racial and ethnic minorities experience disparities in most measures of health-related quality of life, several studies show that African American cancer survivors report higher emotional and spiritual health-related quality of life compared with white cancer survivors (320)Pinheiro LC, Samuel CA, Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Olshan AF, Reeve BB. Understanding racial differences in health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];159:535–43.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(326)Rao D, Debb S, Blitz D, Choi SW, Cella D. Racial/Ethnic differences in the health-related quality of life of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2008 [cited 2019 Dec 17];36:488–96.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. This provides an opportunity for health care providers to recognize and reinforce these areas of strength and to use them to deliver culturally appropriate care and services that help reduce disparities in other measures of health-related quality of life.

Health-related quality of life for racial and ethnic minority cancer patients and survivors is influenced by social, clinical, cultural, behavioral, psychological, and environmental factors (317)Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla G V., Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res [Internet]. Springer; 2007 [cited 2019 Dec 17];16:413–28.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(320)Pinheiro LC, Samuel CA, Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Olshan AF, Reeve BB. Understanding racial differences in health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];159:535–43.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(318)Hao Y, Landrine H, Smith T, Kaw C, Corral I, Stein K. Residential segregation and disparities in health-related quality of life among Black and White cancer survivors. Heal Psychol [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 17];30:137–44.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(324)Hastert TA, Kyko JM, Reed AR, Harper FWK, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Baird TE, et al. Financial Hardship and Quality of Life among African American and White Cancer Survivors: The Role of Limiting Care Due to Cost. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev [Internet]. American Association for Cancer Research; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 17];28:1202–11.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(325)Miller AM, Ashing KT, Modeste NN, Herring RP, Sealy D-AT. Contextual factors influencing health-related quality of life in African American and Latina breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];9:441–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Deeper understanding of the interplay between race and ethnicity and all these is vital to alleviate disparities in health-related quality of life. Improving health-related quality of life is also important because it is linked to cancer-related outcomes, including survival (327)Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim J, Tang J. Surviving cervical cancer: Does health-related quality of life influence survival? Gynecol Oncol [Internet]. Academic Press; 2010 [cited 2019 Dec 17];118:35–42.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Disparities in Financial Toxicity

It is projected that direct spending on cancer care will exceed $157 billion in 2020 (80)Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 16];103:117–28.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For cancer patients and survivors and their families, out-of-pocket medical costs are higher for cancer than for any other chronic disease (328)Bernard DSM, Farr SL, Fang Z. National Estimates of Out-of-Pocket Health Care Expenditure Burdens Among Nonelderly Adults With Cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Dec 17];29:2821–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. As a result of high cancer care costs, many patients experience financial hardship, or financial toxicity (329)Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, Moor JS De, Zheng Z, Khushalani JS, et al. Annual Out-of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Hardship Among Cancer Survivors Aged 18 – 64 Years — United States , 2011 – 2016. 2019;68:2011–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. One recent study showed that 25 percent of cancer survivors reported financial toxicity, as defined by borrowing money or going into debt, filing for bankruptcy, or being unable to cover their copayments (329)Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, Moor JS De, Zheng Z, Khushalani JS, et al. Annual Out-of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Hardship Among Cancer Survivors Aged 18 – 64 Years — United States , 2011 – 2016. 2019;68:2011–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Financial toxicity due to a cancer diagnosis and treatment is associated with lower rates of compliance to therapy, reduced likelihood of receiving follow-up care, skipping medications, and missing appointments (330)Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, Chino F, Samsa GP, Altomare I, et al. Patient-Oncologist Cost Communication, Financial Distress, and Medication Adherence. J Oncol Pract [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 17];10:162–7.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. It is also associated with worse outcomes and poorer quality of life (331)Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];34:980–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].(332)Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, Lathan CS, Ayanian JZ, Provenzale D. Population-Based Assessment of Cancer Survivors’ Financial Burden and Quality of Life: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Oncol Pract [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 17];11:145–50.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, the risk of death has been shown to be 79 percent higher among cancer patients who filed for bankruptcy compared with those who did not file for bankruptcy (331)Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough DK, Overstreet KA, Shankaran V, et al. Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 17];34:980–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Unfortunately, the segments of the U.S. population that shoulder a disproportionate burden of the adverse effects of cancer and cancer treatment, including racial and ethnic minorities, are also at increased risk of experiencing financial toxicity because of the out-of-pocket expenditures caused by a cancer diagnosis and cancer treatment (329)Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, Moor JS De, Zheng Z, Khushalani JS, et al. Annual Out-of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Hardship Among Cancer Survivors Aged 18 – 64 Years — United States , 2011 – 2016. 2019;68:2011–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, it has been reported that 31 percent of African American cancer survivors experience financial toxicity compared with 24 percent of white cancer survivors (329)Ekwueme DU, Zhao J, Rim SH, Moor JS De, Zheng Z, Khushalani JS, et al. Annual Out-of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Hardship Among Cancer Survivors Aged 18 – 64 Years — United States , 2011 – 2016. 2019;68:2011–6.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In another study of lung and colorectal cancer survivors, about 68 percent of African Americans and 58 percent of Hispanics reported financial toxicity compared with 45 percent of whites (333)Pisu M, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, Drentea P, Ashing KT, Fouad M, et al. Economic hardship of minority and non-minority cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: another long-term effect of cancer? Cancer [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 18];121:1257–64.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Financial toxicity extends beyond out-of-pocket direct medical costs and can be caused by indirect costs of lost productivity, such as days lost from work or disability days (334)Financial Toxicity and Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)—Health Professional Version – National Cancer Institute [Internet]. [cited 2019 Jun 20].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. For example, the likelihood of a cancer patient being employed has been shown to drop by almost 10 percentage points and hours worked decline by up to 200 hours in the first year after diagnosis (335)Zajacova A, Dowd JB, Schoeni RF, Wallace RB. Employment and income losses among cancer survivors: Estimates from a national longitudinal survey of American families. Cancer [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Dec 18];121:4425–32.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Among women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer, African American women living in urban areas are almost 50 percent more likely to lose a job or income after their diagnosis compared with white women living in urban areas (336)Spencer JC, Rotter JS, Eberth JM, Zahnd WE, Vanderpool RC, Ko LK, et al. Employment changes following breast cancer diagnosis: the effects of race and place. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18];[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition, among women with breast cancer who were employed at the time of diagnosis, African Americans are significantly less likely to be employed when asked about this at 2 and 9 months after diagnosis compared with whites (337)Bradley CJ, Wilk A. Racial differences in quality of life and employment outcomes in insured women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 18];8:49–59.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Partners of breast cancer survivors also experience a worse financial and employment status as a result of the breast cancer diagnosis, with Hispanic partners significantly more likely to report worse financial and employment status compared with white partners (338)Veenstra CM, Wallner LP, Jagsi R, Abrahamse P, Griggs JJ, Bradley CJ, et al. Long-Term Economic and Employment Outcomes Among Partners of Women With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Oncol Pract [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 18];13:e916–26.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Paving the Way for Health Equity for Racial and Ethnic Minority Cancer Survivors

Understanding the challenges faced by racial and ethnic minority cancer survivors is important to addressing the disparities in cancer morbidity, mortality, and quality of life that they face. Opportunities exist to refine the science of cancer survivorship by integrating biological, health systems, and work of socioecological researchers, developing ways to assess multiple factors influencing disparities, and creating shared data repositories. Through this interdisciplinary team science approach to cancer survivorship research, we can strengthen existing resources and develop targeted interventions to achieve greater health equity.

In addition, to address cancer health disparities, the work of researchers must be informed by the voices of community members. Community-engaged research, which involves partnerships between community members and researchers, is important for catalyzing the translation of scientific knowledge into readily accessible and responsive community education, action, and interventions and for ensuring community receptivity (339)Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health [Internet]. American Public Health Association; 2003 [cited 2019 Dec 18];93:1210–3.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Patient advocates are uniquely positioned to represent their own communities as partners in research projects and will be instrumental in understanding the needs and priorities of the community, defining the research questions and study designs, implementing the studies and disseminating the research results (see sidebar on Patient Advocates Address Cancer Health Disparities). As such, there is a critical need for racial and ethnic minority patient advocates like Ghecemy Lopez who can galvanize effective community-engaged research, resulting in improved health care and health status in these underserved populations.

Ultimately, cancer advocacy is about education and driving policy, practice, social, and funding progress toward the betterment of those affected by this illness. The scarcity of resources and services that are culturally salient for racial and ethnic minorities, along with the growing number of racial and ethnic minority cancer patients and survivors makes a compelling case for their inclusion in advocacy efforts toward building cancer prevention and control systems and a health care system that is responsive to these communities, in order to reduce cancer disparities and bring about health equity.