Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities

In this section, you will learn:

- Extensive research has shown that a long history of racism and contemporary injustices in the United States contributes to and perpetuates health inequities, including cancer disparities.

- Researchers are using a framework of complex and interrelated factors, called social drivers of health, to understand and address cancer disparities.

- Social drivers of health include socioeconomic status, social and built environments, and health care access, and interact with other factors such as mental health, modifiable risk factors, and biological factors to influence health outcomes.

- Drivers of health disparately and adversely affect racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations.

- Constituents across the medical research community are working together to implement strategies at the population, institution, and community levels to reduce cancer disparities and achieve health equity for all.

Disparities resulting from a long history of racism and contemporary injustices in the United States continue to have lasting, multigenerational adverse effects on marginalized populations in all aspects of life, including on health outcomes. The National Institute of Medicine, under mandate from the US Congress, produced the first major report on the topic in 2003 (86)Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Accessed: June 30, 2023. . The report, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, concluded that while socioeconomic factors such as poverty and lack of access to health care are key contributors, long-standing systemic racism is a major reason for the deeply entrenched health disparities in the United States (86)Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Accessed: June 30, 2023. .

Disparities stemming from structural racism (see Sidebar 8), societal inequities, and contemporary injustices are abundant and apparent in racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations in overall health outcomes, as well as in the burden of cancer. In this section, we discuss some of the key drivers of cancer disparities in the United States and highlight selected initiatives and programs that are addressing cancer disparities, with the overarching goal of achieving health equity for all.

Drivers of Health Disparities

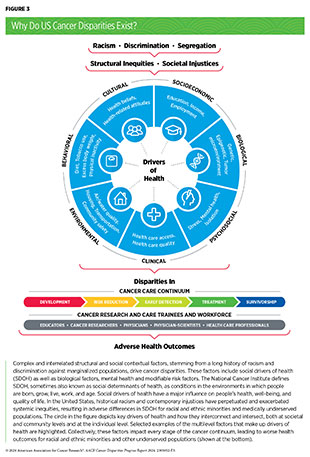

Researchers have proposed many frameworks to understand and address influences that determine health outcomes and contribute to health disparities, including cancer disparities. These frameworks are based on a complex network of interrelated and interconnected factors that include biological factors, mental health, and modifiable risk factors as well as non-clinical factors called social drivers of health (SDOH) (87)Warnecke RB, et al. (2008) Am J Public Health, 98: 1608. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](88)Asare M, et al. (2017) Oncol Nurs Forum, 44: 20. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. According to NCI, SDOH, sometimes also called social determinants of health, are the social, economic, and physical conditions in the places where people are born and where they live, learn, work, play, and get older that can affect their health, factors such as socioeconomic status; housing; transportation; and access to healthy food, clean air and water, and health care services (see Figure 3).

Social drivers of health interplay and, positively or negatively, impact all aspects of a person’s lived experiences. For example, it is well known that balanced and healthy nutritional choices improve overall health and well-being (90)US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Conversely, lack of access to healthy nutrition increases the likelihood of developing health conditions, such as cancer, and contributes to cancer disparities (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors). In this regard, educational campaigns alone are insufficient to promote healthy choices in a neighborhood that does not have grocery stores with healthy food options, or whose residents cannot access grocery stores because of crime and violence or because they do not have the means to afford healthy foods. Instead, the intertwined nature of SDOH requires multiple sectors—education, health, labor, transportation, justice, and housing—to work together and improve access and affordability of healthy food as well as raise awareness of the health benefits of eating well among residents of the neighborhood (see Figure 3). Ongoing research is unraveling multilevel and multifaceted impacts of SDOH on the health of a person, community, and population. In this section, we highlight, with recent examples, some of the key drivers of health, including SDOH, and their contributions to cancer disparities experienced by US racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status—also called SES and usually described as low, medium, and high—refers to the position of an individual in society based on education, income, and type of job, among other indicators. The overarching goal of determining SES is to understand the social health of a society, and to identify and address inequalities among various population groups. In addition to describing individuals, SES can also be used to categorize neighborhoods and other geographically defined areas. The neighborhood-level SES includes the SES of residents and how their social environment influences access to goods and services; crime levels, safety, and policing; and societal norms. For example, residents living in low-SES neighborhoods with limited transportation options, greater travel distances to stores, and fewer supermarkets can experience food insecurity, which is the lack of access to sufficient food or food of adequate quality to meet a person’s needs.

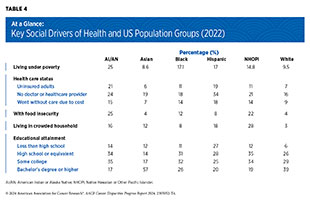

Socioeconomic status is a key driver of disparities, including cancer disparities, in people of all races and ethnicities. For example, findings from a recent study show that women with metastatic breast cancer who lived in neighborhoods with low SES had worse survival compared to those who lived in neighborhoods with high SES, and this association was independent of the race of the patient (91)Puthanmadhom Narayanan S, et al. (2023) NPJ Breast Cancer, 9: 90. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Many racially and ethnically minoritized and medically underserved populations live in conditions that perpetuate low SES. Compared to the White population, a higher proportion of nearly all racial and ethnic minorities were living below the federal poverty level in 2021, had food and housing insecurity, were uninsured, and had less educational attainment (see Table 4).

Individuals or groups with low SES are more likely to experience disparate cancer burdens. One study evaluated the impact of SES on disparities in the outcomes of head and neck cancer in a diverse patient population (92)Karanth SD, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 516. . Findings showed that individuals with the lowest SES had a 45 percent higher mortality rate compared to those with the highest SES (92)Karanth SD, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 516. .

Two recent studies found that residents of neighborhoods with low SES had a higher burden of oral cavity cancers, compared to those living in high-SES neighborhoods (94)Ramadan S, et al. (2023) Oral Oncol, 147: 106607. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](95)Liu Y, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 642. . One study showed a significant difference in 5-year overall survival rates for residents of high and low neighborhood SES, respectively, i.e., 55 percent versus 45 percent for NH White; 36 percent versus 28 percent for NH Black; and 56.5 percent versus 20 percent for Pacific Islander patients (95)Liu Y, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 642. . The second study found that the incidence of oral cavity cancers was 2.4 times higher in White individuals living in neighborhoods with low SES compared to Black individuals living in neighborhoods with high SES (2.86 versus 1.17 cases per 100,000, respectively; (94)Ramadan S, et al. (2023) Oral Oncol, 147: 106607. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]).

Low SES contributes to a higher cancer burden due to many interconnected reasons. For example, individuals with low SES have limited access to quality cancer care services, which leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Neighborhoods with low SES have higher exposures to environmental carcinogens, which are cancer risk factors. Low SES also adversely impacts other aspects of lived experiences, such as mental health. This complexity requires the development of multipronged, effective approaches that provide individuals and neighborhoods with the means and resources to increase their SES.

Social and Built Environments

Racial and ethnic diversity, neighborhood SES, and residential distribution and segregation constitute the social environment of a neighborhood. The built or physical environment of a neighborhood is composed of transportation, public services, and policies and regulations. Together, social and built environments determine, among other attributes, a neighborhood’s cultural norms, collective efficacy, availability of ethnic-serving resources, education quality, and crime, as well as its residents’ access to food, medical facilities, fresh air, clean water, and environments that are free from toxic environmental exposures.

Researchers use several ways to determine the characteristics of a neighborhood. One commonly used metric is called the area deprivation index (ADI). Developed to inform health care delivery and policy, and regularly used in health disparities research to describe neighborhood characteristics, ADI reflects 17 measures across four SES indicators—income, education, employment, and housing quality—and is expressed from 1 (least disadvantaged neighborhood) to 100 (most disadvantaged neighborhood) (96)Kind AJH, et al. (2018) New England Journal of Medicine, 378: 2456. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Decades of research have shown that health outcomes of people are influenced by their social and built environments. As such, the longer an individual resides in a high ADI environment, the more likely they are to experience a disproportionate burden of cancer.

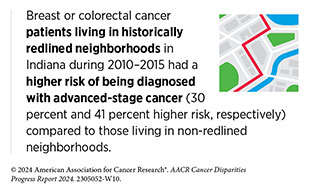

Racial and ethnic minority populations are more likely to live in neighborhoods with poor social and built environments. The reasons for such residential segregation are deeply rooted in centuries of discrimination and structural racism in the United States. One example of structural racism is the egregious practice of redlining, in which financial services are withheld from potential customers who reside in neighborhoods classified as “hazardous” for investment. Although currently illegal, de facto redlining and racial bias in mortgage lending continue to this day. Redlining has segregated many low-income people, often belonging to racially and ethnically minoritized populations, into neighborhoods with poor social and built environments. For example, current neighborhoods exposed to historic redlining have higher air pollution levels (97)Lane HM, et al. (2022) Environ Sci Technol Lett, 9: 345. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is extensive evidence that historic redlining is associated with adverse health outcomes, including a disparate burden of cancer (98)Kraus NT, et al. (2023) Public Health Nurs. 1–10. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](99)Lee EK, et al. (2022) Soc Sci Med, 294: 114696. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](100)Egede LE, et al. (2023) J Gen Intern Med, 38: 1534. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

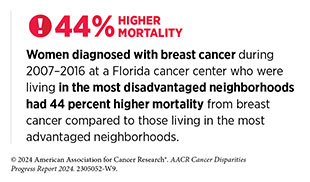

Studies have shown that residents who live in redlined and disadvantaged neighborhoods share a higher burden of cancer. An analysis of US cancer deaths during 2015–2019 in relation to residential segregation found that residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods had a 22 percent higher mortality rate for all cancers combined compared to those living in advantaged neighborhoods (102)Zhang L, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 122. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Findings of the study also revealed that residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods had higher mortality rates for 12 of 13 cancer types reported in the study, ranging from 6 percent higher for cancers of the brain and other parts of the nervous system to 49 percent higher for cancers of the lung and bronchus (102)Zhang L, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 122. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study found that women older than 65 years who were living in redlined neighborhoods had a 26 percent higher chance of dying within 5 years of a breast cancer diagnosis compared to those living in non-redlined neighborhoods (103)Bikomeye JC, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 652. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The intersection of race with poor social and built environments further exacerbates cancer disparities. As one example, a recent study evaluated the association of race and ethnicity with place of residence regarding the diagnosis of the highly aggressive triple-negative form of breast cancer (TNBC) (104)Hernandez AE, et al. (2024) Ann Surg Oncol, 31: 988. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Findings show that women living in low-income neighborhoods were 33 percent more likely to be diagnosed with TNBC compared to women living in high-income neighborhoods. Furthermore, the likelihood of TNBC diagnosis was more than double for NH Black women living in low-income neighborhoods compared to those living in high-income neighborhoods (104)Hernandez AE, et al. (2024) Ann Surg Oncol, 31: 988. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Another study of cancer incidence in metropolitan Detroit during 2012–2016 found that the incidence of prostate cancer among NH Black men was 44 percent lower if they lived in advantaged neighborhoods but was 27 percent higher if they lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods, compared to NH White men living in the corresponding neighborhoods. The study also found that Black adults were more likely to be diagnosed with lung cancer if they lived in a disadvantaged neighborhood, with the likelihood of lung cancer diagnosis increasing with increased disadvantage of the neighborhood (105)Purrington KS, et al. (2023) Cancer Med, 12: 14623. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Evidence presented here underscores how social and built environments can determine health outcomes, including cancer outcomes. Poor social and built environments can limit access and availability of healthy food, expose residents to environmental carcinogens and increase their risk of developing cancer, and/or can restrict access of residents to quality health care services and cause delays in cancer treatment. It is thus unsurprising that the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) department has included promoting healthier environments at home and workplaces as one of the five objectives of the Healthy People 2030 initiative. In addition to such initiatives, it is imperative that constituents across the health care continuum work together to eliminate discriminatory practices—such as modern-day denial of mortgage loans to specific applicants or to specific neighborhoods, also called contemporary redlining—that keep disadvantaged communities and populations under conditions that perpetuate cancer disparities.

Health Care Access

One of the most impactful SDOH is the access of a person to quality health care, which is the degree to which health care services increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes for individuals and populations. Lack of insurance is a key determinant of whether an individual will receive the needed health care. In 2021, nearly 27 percent of US adults ages 18 to 64 who were uninsured delayed or did not receive needed medical care due to cost, compared to a little over 7 percent of those who had either public or private insurance (2)Islami F, et al. (2023) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 136 [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The disparities in access to quality health care are significant. A substantial proportion of racial and ethnic minorities and medically underserved populations in the United States either receive lower-quality health care or lack health care access altogether. For example, compared to White individuals, the proportion of uninsured NHOPI and Black adults in the United States during 2020–2021 was 1.6 times, and that of AI/AN and Hispanic individuals was about three times (see Table 4) (106)KFF. Key Data on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . In addition, racially and ethnically minoritized groups and medically underserved populations experience disparities at multiple levels in their interactions with health care systems (see Sidebar 9).

Lack of access to quality health care has adverse effects across the cancer care continuum. Compared to those with private insurance, uninsured individuals are less likely to be up to date with the recommended cancer screening and are more likely to be diagnosed with cancer at an advanced stage. For example, the number of uninsured women who were not up to date with breast cancer screening in 2021 was nearly double the number of those with public or private insurance (see Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection) (2)Islami F, et al. (2023) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 136 [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similarly, a recent study found that being uninsured or insured by Medicaid accounted for more than half of the estimated disparity in advanced-stage cervical cancer diagnosis among all racial and ethnic minority groups compared to White women (113)Holt HK, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e232985. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Access to quality health care plays a pivotal role in improving health outcomes after a cancer diagnosis. For example, findings of a recent study of women with breast cancer who were active duty, veteran or medical beneficiaries and were treated at a military health care system suggest that disparities in survival outcomes between NH Black and NH White patients are virtually eliminated when equitable access to quality health care is provided (115)Darmon S, et al. (2023) Health Equity, 7: 178. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. However, other important factors contribute to suboptimal interactions between racially and ethnically minoritized patients and health care systems, including distrust in medical research and health care. This distrust has deep roots in historical atrocities, such as experimental gynecologic surgeries performed in the 19th century on enslaved Black women by the Alabama physician James Marion Sims; the Tuskegee Study conducted in the early 20th century in Black people by the medical establishment of the time; and the 1950s development of the first cancer cell line, extensively used in medical research, without the consent of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman with cervical cancer (89)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022. Accessed: June 30, 2023. .

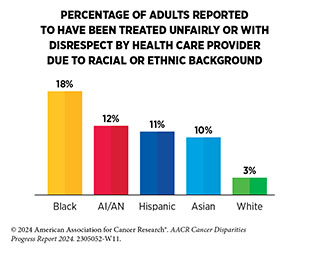

Research has shown that suboptimal communication and interaction between minority and medically underserved patients and their providers can lead to delayed diagnosis and cancer care, as was the case with Oya Gilbert. According to a recent nationwide survey, a large proportion of Black (60 percent), AI/AN (52 percent), Hispanic (51 percent), and Asian (42 percent) individuals indicated that they mentally prepare for possible insults from providers or staff during their health care visits. Findings from the survey also show that Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults who had more health care visits with providers from their own racial and ethnic background had more frequent positive and respectful interactions (114)KFF. Survey on Racism, Discrimination and Health: Experiences and Impacts Across Racial and Ethnic Groups. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . In another study focused on understanding the health needs of SGM individuals residing in the United States, 19.1 percent of transgender men and 16.3 percent of transgender women reported that they were denied health service within the past year or received lower-quality medical care (116)Clark KD, et al. (2023) Int J Equity Health, 22: 162. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Continued and concerted efforts to understand and address the root causes of cancer disparities are necessary to realize the bold vision of achieving health equity. Examples discussed here, as well as a large body of accumulating literature on the topic, underscore the responsibility of all constituents in the medical research community to take proactive and effective measures that include eliminating gaps in health insurance, increasing access to quality health care, and eradicating discrimination and bias across the cancer care continuum.

Mental Health

Mental health includes a person’s emotional, psychological, and social well-being and is an essential part of overall health. Social drivers of health contribute to poor mental health and the resulting stress, both of which are directly and indirectly linked to adverse physical health. Understanding a link between stress and cancer is an area of active research. Another area of ongoing investigation is the impact of early life stress on the cancer burden of the pediatric population. Research has shown that individuals under persistent stress can develop unhealthy behaviors, such as tobacco or alcohol use, both of which are associated with increased risk of cancer (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors) (117)Rodriquez EJ, et al. (2017) J Aging Health, 29: 805. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Conversely, stress related to cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship negatively impacts the mental and psychological well-being of patients with cancer. Furthermore, a cancer diagnosis also adversely affects the mental health of caregivers.

Individuals belonging to racial and ethnic minority populations and medically underserved groups experience higher chronic stress, which is associated with worse health outcomes (118)Pratt-Chapman ML, et al. (2021) Syst Rev, 10: 183. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](119)Fuemmeler BF, et al. (2023) Mol Psychiatry, 28: 1494. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, research has found links between chronic stress and the burden of cancer. A recent review of the literature found an increasing number of studies associating psychological stress with increased risk of developing cancer, including cancers of the breast, prostate, lung and bronchus, and colon and rectum (120)Mohan A, et al. (2022) Eur J Cancer Prev, 31: 585. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For example, one study found that women who had anxiety had a 67 percent higher risk of developing lung cancer (121)Gilham K, et al. (2023) PLoS One, 18: e0281588. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A study of Danish patients diagnosed with cancer between 1995 and 2011 found that, compared to patients who did not have a stress-related mental disorder diagnosis before their cancer diagnosis, patients with a preexisting stress-related diagnosis had a 1.3 times higher rate of overall cancer mortality; the mortality rate was even higher among patients with hematologic malignancies (1.9 times higher), or if the cancer was diagnosed at an advanced stage (1.7 times higher) (122)Collin LJ, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128: 1312. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Substantial evidence indicates that a cancer diagnosis adversely affects the mental and psychological health and well-being of a person. One study found that the likelihood of a mood disorder diagnosis, including depression, increased among patients with prostate cancer compared to the general population (124)Hu S, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Certain population groups are at a higher risk of developing mental health disorders after a cancer diagnosis. A recent study showed that veterans who received a new cancer diagnosis were at a 47 percent higher suicide risk compared to veterans without a new cancer diagnosis (125)Dent KR, et al. (2023) Cancer Med, 12: 3520. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Findings further revealed that the suicide risk was even higher in veterans who received a diagnosis of esophageal cancer (six times higher), head and neck cancer (3.5 times higher), and lung cancer (2.4 times higher), or if the patient was diagnosed with cancer at stage III (2.4 times higher) or stage IV (3.5 times higher) (125)Dent KR, et al. (2023) Cancer Med, 12: 3520. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Studies have also reported that a cancer diagnosis negatively impacts the mental well-being of caregivers. Evidence suggests that siblings of childhood cancer survivors can also experience adverse health outcomes, including cancer risk concerns (126)Morales S, et al. (2022) J Cancer Surviv, 16: 624. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is unsurprising that several minoritized statuses and SDOH also intersect with and impact a person’s mental health. Studies have linked poor mental health with having a low SES (127)Madigan A, et al. (2023) J Affect Disord, 326: 36. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], living under persistent poverty (128)Ridley M, et al. (2020) Science, 370: eaay0214. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods (129)George G, et al. (2023) Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 10: 181. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], and belonging to the SGM community (130)Malik MH, et al. (2023) Am J Mens Health, 17: 15579883231176646. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The relationship between race and ethnicity and mental health is complex. Among adults with any mental illness who, in 2021, reported receiving mental health services in the past year, only 39 percent were Black, 36 percent were Hispanic, and 25 percent were Asian, compared to 52 percent who were White (106)KFF. Key Data on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . More research is needed to comprehensively address the role of mental health in increasing cancer risk as well as its intersection with other factors, such as tobacco and alcohol use, that independently increase the risk of developing cancer.

Modifiable Risk Factors

Modifiable risk factors refer to individual health behaviors that can be changed to decrease the likelihood of developing cancer, and are substantially influenced by SDOH. Tobacco use, poor nutrition, alcohol consumption, and insufficient physical activity are some of the modifiable behaviors that are linked with increased likelihood of developing several types of cancer. These behaviors are often shaped by multiple factors, including SES, social and built environments, and lived experiences of a person, and the extent to which they can be modified depends on the structural barriers faced by minoritized populations.

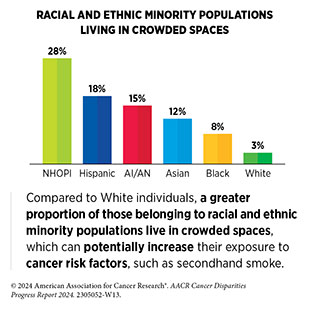

Several medically underserved populations live in conditions that increase their exposure to cancer risk factors and perpetuate unhealthy behaviors (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors). As one example, people who do not smoke and live under disadvantaged conditions (e.g., crowded living spaces without smoke-free policies) are exposed to secondhand smoke, which causes at least 3 percent of all lung cancer deaths each year (an estimated 3,600 deaths in 2023) (131)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2023-2024. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . There are racial and ethnic disparities in exposure to secondhand smoke. During 2017–2020, 17 percent of White individuals were exposed to secondhand smoke. In comparison, 35 percent of Black, 21 percent of Asian, and 18 percent of Hispanic individuals were exposed to secondhand smoke (131)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2023-2024. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

The burden of cancers associated with modifiable risk factors is disparate among racial and ethnic minority populations. In a study of nearly the entire US female population age 20 or older from 2001 to 2018, researchers found substantial racial and ethnic differences in the incidence trends of cancers associated with five major modifiable risk factors: tobacco use, excess body fat, alcohol consumption, insufficient physical activity, and HPV infection (132)Cotangco KR, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. For example, among women ages 20 to 49 years, obesity-associated cancers in Hispanic and NH API women rose at nearly twice the rate of NH White women (2.86 versus 2.19 versus 1.39 percent annual increase, respectively); this increase was the smallest in NH Black women (0.96 percent annual increase). NH API women also had the largest increase in alcohol consumption-associated cancers (1.33 percent increase every year) (132)Cotangco KR, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Among women age 50 years or older, obesity–associated cancers decreased only among NH White women (0.60 percent annual decrease) and increased in all racial and ethnic minorities, with the largest increase observed in API women (0.62 percent annual increase). Similarly, cancers associated with insufficient physical activity decreased 0.74 percent annually in NH White women but increased 0.13 percent in NH Black women (132)Cotangco KR, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E21. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

As noted above, risk factor exposure of racial and ethnic minority groups and disadvantaged populations substantially depends on systemic factors (e.g., lacking the resources to move out of a crowded living space) that may be barriers in reducing their exposure. Moreover, cancer risk factors also contribute to other chronic conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, for which there are similar disparities in burden. Together, the intersecting nature of minoritized statuses and disparate exposures to cancer risk factors because of systemic inequities highlight the complexity in understanding the causal relationship of race and ethnicity with the burden of cancers associated with modifiable risk factors and necessitate a comprehensive approach to investigating and mitigating the root causes of cancer disparities caused by modifiable risk factors.

Biological Factors

Our knowledge of the molecular underpinnings of cancer development has increased tremendously in recent decades. Technological advances in sequencing the human genome with precision have revealed that certain genes and their expression patterns, as well as small changes in their sequences, can increase chances of cancer development (see Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Disparities). Studies have also shown that environmental factors as well as ancestral differences are associated with changes in sequences and expression of cancer-related genes that can potentially increase a person’s risk of developing cancer (134)Virolainen SJ, et al. (2023) Genes Immun, 24: 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](135)Carbone M, et al. (2020) Nat Rev Cancer, 20: 533. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](136)Carrot-Zhang J, et al. (2020) Cancer Cell, 37: 639. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](137)Arora K, et al. (2022) Cancer Discov, 12: 2552. . Furthermore, interplay between SDOH and biological factors directly influences health outcomes.

Researchers have investigated associations between ancestry-related differences in genetic sequences and cancer. According to findings from a recent study, among patients with endometrial cancer, those of African ancestry were 56 percent less likely and those of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry were 62 percent more likely than those with European ancestry to have genetic changes known to cause cancer (138)Liu YL, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 576. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. A systematic review of the literature found that among patients with lung cancer, African and Hispanic ancestries were associated with mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and tumor protein 53 (TP53), respectively (139)James BA, et al. (2023) Front Genet, 14: 1141058. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]; mutations in both genes are well-known drivers of lung cancer (140)Chevallier M, et al. (2021) World J Clin Oncol, 12: 217. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. It is important to note that because of reference datasets used in determining genetic ancestry in such studies, ancestry may reflect historic and structural drivers of health as much as genetic variations.

A key limitation of understanding the role of biological factors in cancer disparities is the fact that much of the genome-wide information on the burden of cancer is based on data from the White population (141)Landry LG, et al. (2018) Health Aff (Millwood), 37: 780. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Researchers are continually working to overcome this shortcoming. For example, in a recent study, researchers reported the development of a computational approach to infer genetic ancestry from existing genomic data from cancer patients that lack such information. The approach is anticipated to double the ability of researchers to investigate links between genetic ancestry and cancer (142)Belleau P, et al. (2023) Cancer Res, 83: 49. .

Research initiatives, such as NIH’s All of Us Research Program, the AACR Project GENIE® (see AACR Initiatives Reducing Cancer Disparities and Promoting Health Equity), and others are beginning to address underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minority populations in genomic databases (see Sidebar 15). As one example, researchers from the program recently released data from nearly 250,000 genome sequences, 77 percent of which are from communities that are historically underrepresented in medical research and 46 percent are individuals from underrepresented racial and ethnic minority populations. Importantly, All of Us researchers identified more than 1 billion genetic variants, including more than 275 million previously unreported genetic variants (143)All of Us Research Program Genomics Investigators. (2024) Nature, 627: 340. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Such studies have the potential to advance the promise of precision medicine (see Figure 6) for all populations.

Recent decades have seen tremendous innovation in technologies and approaches researchers use to understand various aspects of cancer. These advances carry immense potential to help address some of the most intractable challenges in cancer science and medicine, including cancer disparities. However, some of the technologies and approaches may unintentionally worsen cancer disparities (see Sidebar 10). It is vital that all constituents remain cognizant of the potential drawbacks of a rapidly evolving landscape of technological revolution in medicine and take necessary steps to ensure that these advances are equitable in implementation and access for all populations.

Approaches to Address Drivers of Health and Reduce Cancer Disparities

As noted in the previous section, SDOH intersect with all aspects of life, impact lived experiences, and influence health outcomes of a person across the life span. Addressing SDOH can not only improve overall health but also help reduce cancer disparities that are deeply rooted in social and economic disadvantages experienced by racial and ethnic minority groups and medically underserved populations. Constituents across the continuum of cancer care are taking multipronged approaches to address SDOH at various levels, with the overarching goal of achieving health equity for all. In this section, we highlight how some of these approaches are helping us to understand and mitigate cancer disparities.

Policy-focused Approaches

Evidence-based interventions and policies implemented at the population level have the potential not only to improve the nation’s health but also strengthen the US economy. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine highlighted in its 2019 report, Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health, that addressing social needs, such as transportation, housing, and education, at the government level can significantly improve health outcomes.

Several long-term initiatives are aimed at improving health outcomes at a population level. One such initiative is the US HHS department’s Healthy People 2030 initiative. Addressing SDOH is a key focus of Healthy People 2030, which contains multipronged approaches to improve social and built environments in which people live (144)US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health People 2023. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . As another example of a population-level intervention, there is significant evidence that The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has decreased the number of uninsured individuals, thus mitigating lack of access to health care, which is a key driver of health for a large proportion of the population (see Health Care Access) (145)Zhao J, et al. (2020) CA Cancer J Clin, 70: 165. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Consequently, the ACA-associated Medicaid expansion has been linked to an increase in adherence to routine cancer screening, cancer diagnosis at an early stage when it is easier to treat the disease, increase in utilization of cancer treatments, reduction in disparities, and improvements in survival rates (146)Moss HA, et al. (2020) J Natl Cancer Inst, 112: 779. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

There are also examples of evidence-based strategies being implemented at multiple levels to help improve one or more SDOH. For example, lack of transportation because of insufficient resources, also called transportation insecurity, can lead to delayed or missed cancer care and additional economic and health costs later in life (147)Graboyes EM, et al. (2022) J Natl Cancer Inst, 114: 1593. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](148)Jiang C, et al. (2023) Journal of Clinical Oncology, 41: 6534. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has developed the Non-Emergency Medical Transportation (NEMT) program, which provides eligible Medicaid beneficiaries rides to medical appointments and is the largest program addressing health care–related transportation needs (149)Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Non-Emergency Medical Transportation. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Another federal program addressing transportation insecurity as one of the ways to improve health outcomes is the Veterans Transportation Program, which offers veterans travel assistance to and from their Veteran Affairs health care facilities (150)US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Transportation Program (VTP) – Health Benefits. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Other constituents, such as health care systems, nonprofit organizations, and pharmaceutical agencies, are also addressing transportation insecurity (147)Graboyes EM, et al. (2022) J Natl Cancer Inst, 114: 1593. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There is some evidence that such programs improve health outcomes for patients and increase savings for the health care system by reducing the number of missed appointments, among other benefits (151)Damico N, et al. (2020) Int J of Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 108: e388. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Many patients with cancer, especially those belonging to racial and ethnic minority populations and medically underserved groups, experience food insecurity, which is the condition of not having access to sufficient food or food of an adequate quality, to meet a person’s basic needs (153)Raber M, et al. (2022) J Natl Cancer Inst, 114: 1577. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are several programs and initiatives to address food insecurity among patients with cancer. The FOOD (Food to Overcome Outcome Disparities) program, launched in 2011 by a New York City comprehensive cancer center, is one such example (154)Gany FM, et al. (2020) J Health Care Poor Underserved, 31: 595. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The FOOD program is a network of food pantries, coupled with cancer nutrition education and food navigators, that are embedded in 15 safety net hospitals and comprehensive cancer center clinics throughout the Greater New York metropolitan area. Once a patient with cancer is identified to have food insecurity, the FOOD pantries provide groceries with enough food for 10 meals for one person. A randomized controlled trial comparing FOOD interventions found that food insecurity among patients with cancer who participated in the program decreased significantly at 6 months of study enrollment (155)Gany F, et al. (2022) Journal of Clinical Oncology, 40: 3603. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As another example of initiatives to address challenges faced by medically underserved populations, the Louisiana Department of Health and Louisiana Housing Authority partnered to provide a Permanent Supportive Housing program to Medicaid beneficiaries in an effort to prevent and reduce homelessness. Preliminary analysis reveals a 24 percent reduction in Medicaid costs and a significant reduction in hospitalization and emergency department utilization (156)Human Services Research Institute. Evaluation of the Louisiana Permanent Supportive Housing Initiative. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

The federal government has implemented multiple programs providing stable and safe housing, nutrition and food access, social and economic mobility, and social services programs (157)US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Health Policy. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts. Accessed: March 17, 2024. (158)The White House. The U.S. Playbook to Address Social Determinants of Health. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Because of the scale of population-level interventions, additional research and routine evaluation of the implemented programs are necessary to fully understand the impact of such efforts on addressing cancer disparities.

Research-focused Approaches

Approaches focused on understanding and addressing SDOH can help improve health outcomes and prevent disease in the long term. NIH, NCI, CDC, and cancer-focused organizations are collaborating with each other and with institutes across the nation to research, develop, and implement interventions that are meaningful to the communities they are serving. At NIH, the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) is leading research efforts to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. For example, NIMHD has partnered with NCI to launch the RESPOND (Research on Prostate Cancer in African American Men: Defining the Roles of Genetics, Tumor Markers, and Social Stress) study, one of the largest efforts to identify the environmental and genetic factors related to disproportionately high diagnoses of aggressive prostate cancer in Black men (159)National Institutes of Health. NIH and Prostate Cancer Foundation launch large study on aggressive prostate cancer in African-American men. Accessed: March 2017, 2024. . The initiative has funded a national network of prostate cancer researchers across 13 institutes to recruit over 12,000 Black men who were recently diagnosed with prostate cancer, with the aim to collect both biological and nonbiological information that will help researchers understand and address factors that contribute to the disproportional diagnosis of aggressive prostate cancer in Black men.

Similarly, NIH, NCI, and other constituents in the cancer care community have launched several research efforts to understand and address cancer disparities. Some examples include the NCI-funded Multiethnic Cohort Study, an epidemiological study that follows over 215,000 residents of Hawai‘i and Los Angeles for development of cancer and other chronic diseases (160)University of Hawai‘i Cancer Center. The Multiethnic Cohort Study. Accessed: March 26, 2024. ; the Southern Community Cohort Study, also funded by NCI, to understand the root causes of cancer disparities (161)Signorello LB, et al. (2010) J Health Care Poor Underserved, 21: 26. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]; and the Black Women’s Health Study, to understand causes of chronic diseases, including breast cancer, among Black women (162)Rosenberg L, et al. (1995) J Am Med Womens Assoc, 50: 56. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (see Sidebar 15). One of NIH’s major initiatives addressing cancer disparities is the All of Us Research Program (163)National Institutes of Health. All of Us Research Program. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The program aims to gather health data, such as genetic information, electronic

health records, lifestyle factors, and environmental exposures, from one million or more people for creating a diverse and representative research cohort that reflects the demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic diversity of the US population. As of February 2024, the program has recruited more than 763,000 participants, more than 80 percent of whom are underrepresented in biomedical research and about 45 percent are from racial and ethnic minorities (164)National Institutes of Health. NIH All of Us. Data Snapshots. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The program provides a template to initiate similar approaches focused on collecting cancer data for research purposes.

NCI also plays a pivotal role in funding institute-level initiatives aimed to help reduce cancer disparities. The NCI Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (CRCHD) plays an essential role in training a diverse cancer research and care workforce through a myriad of highly effective initiatives and programs (see Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce). The NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) is another example of NCI’s efforts to reduce disparities. NCORP brings cancer research studies and results to patients in their own communities across the United States. This cross-institutional program focuses on increasing clinical trial participation, addressing social drivers of disparities, and evaluating differential outcomes in racially and ethnically minoritized populations and medically underserved groups (166)The NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP). Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The program reported in 2020 that the proportion of racial and ethnic minority patients in NCI-funded clinical trials nearly doubled from 14 percent in 1999 to 25 percent in 2019 (167)The Cancer Letter. Participation by minority racial, ethnic groups in NCI-funded trials nearly doubles in 20 years. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Currently, the NCORP network includes seven research sites that develop and coordinate clinical studies and cancer care research for 32 community sites, as well as for 14 community sites that serve racial and ethnic minorities and medically underserved populations, to bring NCI-approved clinical studies to more than 1,000 locations at diverse, community-based hospitals and private practices across the United States (166)The NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP). Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

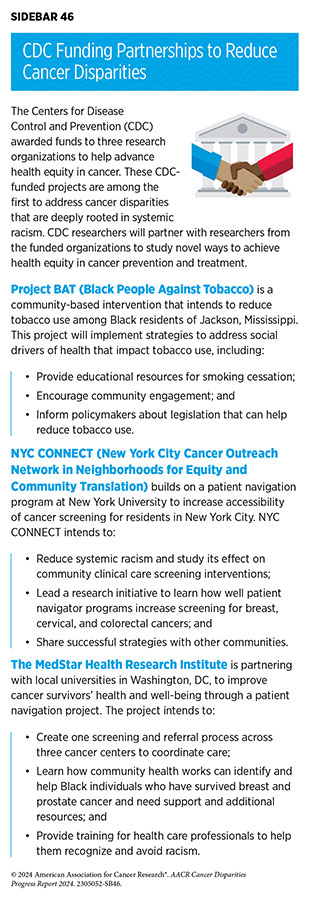

Many of CDC’s programs and initiatives are also focused on reducing racial and ethnic health disparities (see Sidebar 46). For example, Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) is a national program that provides funds to state and local health departments, tribes, universities, and community-based organizations to build strong partnerships to guide and support the program’s mission to reduce health disparities (168)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . As one example, in December 2023, the program awarded funds to the American Indian Cancer Foundation to improve health and prevent chronic diseases, including cancer, through encouraging healthy food choices, promoting safe and accessible physical activity, and implementing tobacco prevention and control policies in Native communities residing in Oklahoma (169)American Indian Cancer Foundation. American Indian Cancer Foundation Receives Funding to Improve Health and Prevent Chronic Disease in Native Communities. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

It is well known that suboptimal recruitment of underrepresented populations in cancer research is a pervasive challenge that perpetuates disparities (see Disparities in Cancer Clinical Trial Participation). To address this challenge, six institutions across the United States formed the Alliance to Advance Patient-Centered Cancer Care (AAPCCC). Each site identified opportunities within their cancer programs to increase their reach to underrepresented populations that ranged from racially and ethnically minoritized groups to rural residents. Member sites implemented four evidence-based interventions: patient navigation; culturally tailored community outreach; digital health; and addressing social needs, such as transportation insecurity. Preliminary findings from the collaborative showed an overall 38 percent recruitment of patients who were reflective of the diversity of the population the member sites intended to reach (170)Arring N, et al. (2023) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 21: 481. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Research-focused approaches highlighted here are select examples of the ways constituents across the cancer care continuum are collaborating to accelerate progress against cancer disparities. There are many more initiatives at the levels of federal agencies, cancer centers, and other cancer-focused organizations, all with the ultimate goal to eliminate cancer disparities and achieve health equity.

Community-focused Approaches

A community provides support and a sense of belonging during difficult times. Research has shown that individuals living in supportive communities experience improved mental and physical health (171)Harandi TF, et al. (2017) Electron Physician, 9: 5212. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](172)Hoffman A, et al. The Many Faces of Social Connectedness and Their Impact on Well-being. In: Spini D, Widmer E, editors. Withstanding Vulnerability throughout Adult Life: Dynamics of Stressors, Resources, and Reserves. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023. p 169. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, community engagement is a way to establish trust with health care providers and reach racial and ethnic minority populations and medically underserved populations. Community-based involvement may enhance healthy behaviors, increase adherence to cancer screening, encourage participation in clinical trials, and improve the receipt of treatment (173)Kale S, et al. (2023) Cureus, 15: e43445. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](174)Wangen M, et al. (2023) Cancer Causes Control, 34: 45. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

In the United States, numerous efforts have prioritized community-focused approaches to address health disparities. As one example, the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF), established by the US HHS department in 1996, develops evidence-based guidance for community-level interventions to promote health and prevent disease. Based on the available evidence, CPSTF recommended in the 2022 Annual Report to Congress that patient navigation services should be provided to medically underserved communities to increase cancer screening (175)Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2021 Annual Report to Congress. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Considering the importance of engaging the community to improve health, NCI requires that community outreach and engagement spans all aspects of an NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center’s programs, including basic, clinical, translational, and population research (176)Hiatt RA, et al. (2022) Cancer Prev Res (Phila), 15: 349. .

Researchers are developing innovative ways to connect scientists with community members to inform and involve the general population in clinical research. Florida-California Cancer Research, Education and Engagement (CaRE2) Health Equity Center is one such program (177)Hensel B, et al. (2023) J Cancer Educ, 38: 1429. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The program, which encompasses three institutes located on the US East and West coasts, is designed to eliminate cancer disparities in Black and Hispanic populations living in California and Florida. The program, conducted virtually over 13 weeks, provides educational materials in English and Spanish for participants to learn more about prostate, lung, and pancreas cancers. A recent report from the program shows that the knowledge among participants about breast and prostate cancers substantially increased at the end of the 13-week course (177)Hensel B, et al. (2023) J Cancer Educ, 38: 1429. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

CDC also funds partnerships among constituents to increase community engagement in developing comprehensive cancer control strategies—state-level roadmaps to identify regional needs to reduce cancer burden and increase health equity. As one example, the Illinois Department of Public Health, with funding from CDC, partnered with its statewide coalition, the Illinois Cancer Partnership, to develop the 2022–2027 Illinois Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan. The partnership convened town halls and focus groups of diverse participants that included cancer survivors, caregivers, racial and ethnic minority groups, and rural residents. Based on feedback from participants, the partnership developed the 2022–2027 Illinois Comprehensive Cancer Control Plan, which was passed by the Illinois state legislature in March 2022 (178)Carnahan LR, et al. (2023) Prev Chronic Dis, 20: E69. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Community engagement plays an important role in addressing cancer disparities by engaging medically underserved communities in designing, implementing, and evaluating initiatives and interventions to address their cancer care needs (173)Kale S, et al. (2023) Cureus, 15: e43445. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. As one example, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 clinical trials revealed that interventions led by community health workers doubled the participation of all racial and ethnic groups in colorectal cancer screening programs compared to those receiving no interventions (179)Rana T, et al. (2023) Cancer Nurs, 10: 100287. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Similarly, two systematic reviews of thousands of studies have found that interventions involving patient navigation, especially those that are culturally tailored, significantly increase racial and ethnic minority patient engagement across the cancer care continuum and improve health outcomes (180)Nouvini R, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128: 3860. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](181)Chan RJ, et al. (2023) CA Cancer J Clin, 73: 565. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Current evidence shows that community-level approaches not only increase engagement and participation of racial and ethnic minority populations and medically underserved groups in efforts to reduce cancer burden but also build trust in health care systems, inspire advocacy and policy changes, and develop long-lasting partnerships, all of which reduce cancer disparities.

Next Section: Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Disparities Previous Section: The State of US Cancer Disparities in 2024