- Funding Research and Supporting Innovative Programs to Address Disparities and Promote Health Equity

- Collaborative Resources to Advance Research for Health Equity

- Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Prevention

- Regulations to Reduce the Disparate Harms of Tobacco Products

- Policies to Promote Environmental Justice

- Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Screening and Follow-up Care

- Policies to Address Disparities in Screening and Surveillance for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes

- Policies to Address Disparities in Clinical Research and Care

- Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers in Trial Design

- Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers for Patients

- Improving Access to High-Quality Cancer Care

- Sustainably Supporting Patient Navigators and Community Health Workers

- Advocacy for Universal Access to High-speed Broadband Internet

- Coordination of Health Disparities Research and Programs Within the Federal Government

Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Science-based Public Policy

In this section, you will learn:

- Federal funding through NIH, FDA, CDC, CMS, and other agencies is fundamental to addressing many of the issues that perpetuate cancer disparities.

- Policies that are aimed at improving cancer prevention and early detection will help reduce cancer disparities.

- A recently enacted law to require clinical trial sponsors to submit Diversity Action Plans to the FDA as part of their clinical study protocols will increase enrollment of underrepresented populations in clinical trials, thereby improving access to innovative cancer therapies for all patients.

- With the growing use of telemedicine, universal access to high-speed broadband Internet is vital to health equity.

Disparities in cancer research, prevention, and care continue to disproportionately affect historically marginalized populations. Achieving cancer health equity will require focused and multidirectional efforts from government, communities, health systems, researchers, nonprofit organizations, and all other stakeholders in the cancer care ecosystem. This section focuses on federal initiatives and science-based policy solutions to reduce cancer disparities and promote health equity.

Funding Research and Supporting Innovative Programs to Address Disparities and Promote Health Equity

Federal funding for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and other agencies is crucial for advancing our understanding of cancer disparities and developing effective strategies to address them. In recent years, federal agencies have augmented existing research programs and created new research initiatives designed to expand our knowledge of diverse populations and the health challenges they face.

The NIH-wide UNITE Initiative seeks to address structural racism at NIH and in the broader medical community research and promote health equity research (964)National Institutes of Health. Ending Structural Racism. UNITE. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . As part of this initiative, the agency has created new sources of support to study and reduce health disparities across populations, such as the NIH Common Fund Transformative Research to Address Health Disparities and Advance Health Equity program (1007)NIH Common Fund. Transformative Research to Address Health Disparities and Advance Health Equity. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The NIH UNITE initiative has also led to the creation of the NIH Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS) initiative, which seeks to develop, implement, and evaluate structural interventions to improve health equity through community-driven partnerships. NIH intends to budget approximately $400 million over 10 years for ComPASS activities (965)The National Institutes of Health. The UNITE Progress Report 2021-2022. Accessed: March 17, 2024. (1008)National Institutes of Health. Office of Strategic Coordination-The Common Fund. Community Partnerships to Advance Science for Society (ComPASS). Accessed: March 26, 2024. .

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) is a leader of these initiatives and a locus for federal health equity research. With a fiscal year (FY) 2023 budget of approximately $524 million, NIMHD funds both intramural and extramural research projects organized around major themes, including clinical and health services research, integrative biological and behavioral research, and community health and population sciences (1009)National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities. Research Interest Areas. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Each of the NIH Institutes and Centers, including NCI, has also expanded its research programs to address disparities (see Sidebar 45). For example, NCI recently coordinated a new $50 million Persistent Poverty Initiative. This program entails the creation of five new Centers for Cancer Control Research in Persistent Poverty Areas that will implement and study interventions for cancer prevention (1010)National Cancer Institute. NCI awards $50 million for new Persistent Poverty Initiative. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

The NCI Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (CRCHD) remains a key part of NCI’s research efforts to address the unequal burden of cancer across the United States (1011)National Cancer Institute. NCI Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . CRCHD runs many programs that facilitate the expansion of scientific partnerships between institutions serving underserved communities and NCI-designated cancer centers, broaden opportunities for scientific training, and build community partnerships to improve cancer screening.

Federal funding is also helping to reduce disparities in personalized medicine research. Breakthroughs in genomic sequencing are unlocking the potential for personalized medicine based on a deeper understanding of an individual’s genetics. However, racial and ethnic minorities are underrepresented in genomics studies and databases. To address these gaps, programs such as the NIH All of Us Research Program are building genomic and other health research resources across populations (1012)National Human Genome Research Institute. Diversity in Genomic Research. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

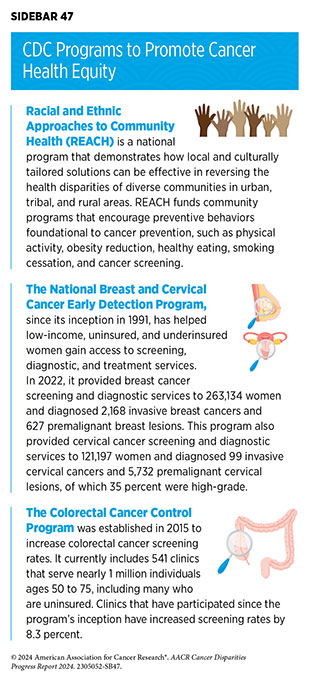

CDC operates many public health programs to reduce cancer disparities and improve health equity (see Sidebar 46). CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control (DCPC) works to improve equity in cancer control, including through grants to state and local health departments. Its public health strategies include studying awareness of cancer risk among diverse groups, providing access to cancer screening to medically underserved populations, and identifying other barriers to cancer prevention and treatment (1013)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What CDC Is Doing to Achieve Equity in Cancer Control. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . DCPC is playing a central role in the CDC-wide CORE Health Equity Science and Intervention Strategy, which seeks to embed health equity in all the agency’s projects to improve public health (see Sidebar 47) (1014)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s CORE Commitment to Health Equity. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Collaborative Resources to Advance Research for Health Equity

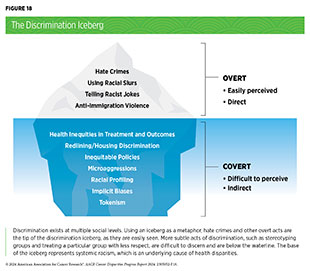

Present-day disparities in cancer risk and outcomes often stem from underlying policies, laws, structures, and beliefs ingrained in our society. Some of these policies are or were intentionally discriminatory toward racial and ethnic minority communities and continue to produce broad negative impacts on opportunities for education, employment, housing, and access to healthy nutrition (see Figure 18). These negative impacts resulting from centuries of race-based policies are commonly known as structural or systemic racism. For example, redlining (see Sidebar 8) is a racist practice stemming from the Homeowners Loan Corp and the Federal Housing Administration’s use of color-coding maps to indicate where it was perceived as “safe” to insure mortgages. Anywhere Black individuals lived was marked as red to denote these places were “risky” neighborhoods, and these designations have had lasting effects on health disparities (see Sidebar 8). Redlining prevented Black individuals from building home equity and has furthered health disparities associated with less resourced schools, increased environmental hazards, reduced air quality, decreased availability of health care facilities, and increased risk of low birth weight (701)Khalil M, et al. (2024) Ann Surg Oncol, 31: 1477. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](1016)Nardone A, et al. (2021) Environ Health Perspect, 129: 17006. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Addressing and combating ways patients are impacted by social drivers of health, including racist policies like redlining, are essential in achieving health equity (see Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities).

Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Prevention

Regulations to Reduce the Disparate Harms of Tobacco Products

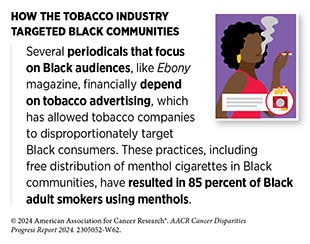

Scientific evidence demonstrates that tobacco smoking causes 18 different types of cancer and is the top modifiable risk factor for cancer-related deaths (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors). Over the past 60 years, the percentage of US adults who currently smoke has been reduced from 42.4 percent to 11.5 percent through policies such as smoke-free laws, tobacco taxes, advertising restrictions, evidence-based smoking cessation programs, and awareness campaigns. However, predatory marketing practices from the tobacco industry toward racial and ethnic as well as sexual and gender minority individuals have resulted in persistently higher smoking rates compared to NH White individuals, especially among youth (1017)Public Health Law Center. The Tobacco Industry & the Black Community: The Targeting of African Americans. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

The tobacco industry has aggressively targeted racial and ethnic minority communities with menthol cigarettes for decades. Overall, 38.8 percent of Americans who smoke use menthol cigarettes, and largely due to predatory marketing practices, 85 percent of Black individuals who smoke use menthol cigarettes (331)Birdsey J, et al. (2023) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 72: 1173. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Extensive evidence indicates that menthol cigarettes increase smoking initiation, progression to frequent smoking, exposure to nicotine, and reduce smoking cessation success (1018)Villanti AC, et al. (2017) BMC Public Health, 17: 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](1019)Ross KC, et al. (2016) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 25: 936. (1020)Okuyemi KS, et al. (2007) Addiction, 102: 1979. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (TCA) prohibited most flavors of cigarette products but allowed the tobacco industry to continue marketing menthol cigarettes and flavored cigars. However, the TCA asked FDA to determine if continued availability of menthol cigarettes was “appropriate for the protection of public health.” In 2013, FDA concluded that “menthol cigarettes pose a public health risk above that seen with nonmenthol cigarettes” (1021)Los Angeles Times. FDA moves toward restricting menthol in cigarettes. Accessed: March 27, 2024. .

AACR and many other public health–focused organizations have consistently advocated for FDA to prohibit menthol cigarettes, including through a formal Citizen Petition in 2013 (1022)Tobacco Control Legal Consortium et al. Citizen Petition to Food & Drug Admin., Prohibiting Menthol as a Characterizing Flavor in Cigarettes (Apr. 12, 2013). Accessed: March 28, 2024. . In April 2022, FDA responded to the Citizen Petition with a draft product standard to prohibit the manufacture, distribution, or sale of menthol cigarettes (1023)Food and Drug Administration. Tobacco Product Standard for Menthol in Cigarettes. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , which received hundreds of thousands of public comments. As of the writing of this report, the menthol rule has not been finalized. Scientific studies estimate that between 25 and 64 percent of adults who smoke menthol cigarettes would quit if menthol cigarettes were not available (1024)Cadham CJ, et al. (2020) BMC Public Health, 20: 1055. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, a federal menthol ban is estimated to save 650,000 lives by 2060, with a large proportion of those lives saved among Black individuals (1025)Levy DT, et al. (2023) Tob Control, 32: e37. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In November 2022, California residents voted in favor of Proposition 31, which banned nearly all flavored tobacco products including menthol cigarettes (1026)Public Health Law Center. Proposition 31 in California Passed! Now What? Accessed: March 17, 2024. . However, tobacco companies have effectively circumvented the flavor ban by using synthetic chemicals that provide a cooling sensation without a “flavor” (1027)The New York Times. R.J. Reynolds Pivots to New Cigarette Pitches as Flavor Ban Takes Effect. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . It is important that a comprehensive ban on menthol cigarettes closes this loophole by banning any additives that provide a cooling sensation to mask the harshness of smoke. Furthermore, increased support for evidence-based smoking cessation resources and programs is critical to maximize the public health benefits of banning these extremely addictive products.

Similar to menthol, all flavored tobacco products significantly increase smoking initiation (1028)Nyman AL, et al. (2016) Tob Regul Sci, 2: 239. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](1029)Ambrose BK, et al. (2015) JAMA, 314: 1871. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](1030)Kong G, et al. (2017) Tob Regul Sci, 3: S48. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Two-thirds of adults who currently use “little cigars” or “cigarillos” have smoked these products with flavors other than tobacco (1028)Nyman AL, et al. (2016) Tob Regul Sci, 2: 239. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Additionally, Black and Hispanic adults are more than twice as likely as White adults to smoke little cigars or cigarillos. In April 2022, FDA proposed a draft product standard banning the manufacture, distribution, or sale of flavored cigars (1031)Federal Register. Tobacco Product Standard for Characterizing Flavors in Cigars. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , but as of writing has not been finalized. This policy is estimated to prevent 112,000 youth and young adults from initiating cigar smoking every year, and therefore decrease premature deaths from cigar smoking by 21 percent (1032)Rostron BL, et al. (2019) Int J Environ Res Public Health, 16: 3234. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Smoking-related health disparities are exacerbated by inconsistent insurance coverage for evidence-based smoking cessation therapies. Among US adults who attempted to stop smoking in 2015, 34.3 percent of non-Hispanic White (NHW) adults used evidence-based medication or counseling (321)Zhang L, et al. (2019) Am J Prev Med, 57: 478. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In comparison, 28.9 percent of Black adults, 20.5 percent of Asian adults, and 19.2 percent of Hispanic adults used evidence-based cessation methods. Lack of health insurance was a key reason for these disparities; only 21.4 percent of adults without health insurance used evidence-based methods. Expanding Medicaid, improving cessation benefits within Medicaid and Medicare, and eliminating other barriers could greatly improve the use of evidence-based cessation methods that reduce overall health care costs (1033)Richard P, et al. (2012) PLoS One, 7: e29665. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] (1034)Ramsey AT, et al. (2019) BMJ Open, 9: e030066. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, increased funding for federal awareness campaigns and cessation support services, such as SmokeFree.gov and CDC’s “Tips from Former Smokers,” with focused initiatives for racial and ethnic and/ or sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations could help address tobacco-related disparities (1035)smokefree.gov. Smokefree. Accessed: March 17, 2024. (1036)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips From Former Smokers. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Policies to Promote Environmental Justice

The term “environmental justice” refers to efforts that advance the just treatment of all people by ensuring they are protected from disproportionate environmental health risks and can live in a healthy, sustainable environment (1038)US Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Justice. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Racial and ethnic minorities and other marginalized groups are disproportionately harmed by exposures to environmental carcinogens, including radon, petrochemicals, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and pesticides (442)Collins MB, et al. (2016) Environ Res Lett, 11: 015004. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](443)Johnston J, et al. (2020) Curr Environ Health Rep, 7: 48. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In turn, these exposures lead to higher cancer rates and mortality (102)Zhang L, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 122. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These outcomes are the result of discriminatory policies, including redlining and the construction of polluting industrial facilities and waste disposal sites in marginalized communities (98)Kraus NT, et al. (2023) Public Health Nurs. 1–10. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](99)Lee EK, et al. (2022) Soc Sci Med, 294: 114696. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](100)Egede LE, et al. (2023) J Gen Intern Med, 38: 1534. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

As part of the Cancer Moonshot, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has undertaken and expanded a series of initiatives to prevent exposure to environmental carcinogens and promote environmental justice (1039)US Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Efforts to Reduce Exposure to Carcinogens and Prevent Cancer. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The National Radon Action Plan (NRAP), an EPA-led public-private partnership between government, industry, and not-for-profit organizations, is continuing its efforts to eliminate preventable, radon-induced lung cancer (1040)US Environmental Protection Agency. The National Radon Action Plan – A Strategy for Saving Lives. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . First established in 2015, the NRAP has saved approximately 2,000 lives annually through increased radon testing requirements in the home finance and insurance sectors, updated building codes, improved radon detection and mitigation strategies, and better public education of radon risks (1041)National Radon Action Plan. Reflections on the National Radon Action Plan’s (NRAP) Progress, 2015–2020. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The current NRAP from 2021 to 2025 seeks to build on these successes by expanding risk reduction in building codes and real estate transactions, providing financial support for radon mitigation to low-income and other historically marginalized communities, and growing the workforce of certified radon mitigation professionals, among other strategies (1042)National Radon Action Plan. The National Radon Action Plan 2021–2025 Eliminating Preventable Lung Cancer From Radon in the United States by Expanding Protections for All Communities and Buildings. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

EPA has a central role in the regulation of harmful synthetic chemicals under the authorities granted to the agency by the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). (1043)US Environmental Protection Agency. Summary of the Toxic Substances Control Act. Accessed: March 17, 2024. The agency has recently pursued regulatory activities to curtail the manufacture and use of environmental carcinogens including trichloroethylene and methylene chloride (1044)US Environmental Protection Agency. Biden-Harris Administration Proposes Ban on Trichloroethylene to Protect Public from Toxic Chemical Known to Cause Serious Health Risks. Accessed: March 17, 2024. (1045)US Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Proposes Ban on All Consumer, Most Industrial and Commercial Uses of Methylene Chloride to Protect Public Health. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

The agency has also recently pursued a series of regulatory actions to regulate PFAS. In September 2022, EPA proposed to designate two PFAS (PFOA and PFOS) as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) also known as Superfund (1046)US Environmental Protection Agency. Proposed Designation of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS) as CERCLA Hazardous Substances. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Such action would increase reporting requirements and enable enforcement related to the release of these chemicals into the environment. In March 2023, EPA proposed a set of legally enforceable levels for six types of PFAS in drinking water (1047)US Environmental Protection Agency. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Many of EPA’s activities to advance environmental justice are coordinated through the Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights (OEJECR). OEJECR creates tools such as EJScreen to provide consistent information to the public about the burden of environmental hazards on communities to help enable action, including reduction of exposure to carcinogens (1048)US Environmental Protection Agency. EJScreen: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The Office also provides grants and technical assistance to communities and multi-stakeholder partnerships to improve environmental health in marginalized communities, including the Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving Cooperative Agreement Program and the Environmental Justice Government-to-Government Program (1049)US Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Justice Grants, Funding and Technical Assistance. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Screening and Follow-up Care

Addressing disparities in cancer screening and follow-up care will require patient centricity when navigating the health care system (1050)Fiscella K, et al. (2011) J Health Care Poor Underserved, 22: 83. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. While policy measures like the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) have greatly reduced some financial barriers to cancer screenings, cost remains a major factor. Colonoscopy screenings are essential for addressing colorectal cancer; however, there can be gaps in what insurance covers. While stool-based tests can be fully covered under insurance, subsequent colonoscopies can be subject to a deductible or copay, as they are no longer considered preventive (1051)Brian Dooley. Screening vs. Diagnostic Colonoscopy: What’s The Difference? – Gastroenterologist San Antonio. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . One way to address this financial barrier to care is to support bills like The Colorectal Cancer Payment Fairness Act (H.R.3382), introduced by Representative Donald Payne, Jr. (1052)Congress.gov. H.R.3382 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Colorectal Cancer Payment Fairness Act. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . This bill would eliminate the coinsurance requirement for diagnostic colorectal cancer screening tests under the Medicare program (1053)National Cancer Institute. Federal Health Legislation. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Black individuals have a 20 percent higher chance of getting colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer is the second leading cancer death in AI/AN communities (1054)Pfizer. Understanding Healthcare Disparities in Colorectal Cancer. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , so enacting policies like H.R.3382 is a step towards addressing these disparities.

Many societal factors have resulted in mass incarceration that disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minority groups (1055)Ashley Nellis, Ph.D. The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . There is a lack of data on whether incarcerated individuals receive cancer screenings when needed (1056)Ramaswamy M, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 1128. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Incarcerated individuals also face numerous elevated cancer risk factors, including higher infection rates with HPV (1057)Salyer C, et al. (2022) J Womens Health (Larchmt), 31: 533. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE], hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV (1058)Dolan K, et al. (2016) Lancet, 388: 1089. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Lack of screening for incarcerated individuals also leads to diagnoses at later stages, which can be more difficult to treat.

Community outreach and engagement are crucial to understand the needs of the local community, navigate the health care system, build trust in research, and ultimately address disparities. Funding for short-term housing near cancer treatment centers, transportation assistance, flexible appointment hours, and Medicaid expansion are potential solutions to address these difficulties. In addition, supporting community health workers in the Latin community, sometimes referred to as “promotoras de salud,” addresses the need for culturally competent support systems and can be essential in establishing trust with their community (1059)Joseph AK, et al. (2022) Pediatr Dermatol, 39: 182. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These challenges and opportunities will require complex and unified efforts by providers, policymakers, and communities, but are essential to dismantle health care disparities.

Policies to Address Disparities in Screening and Surveillance for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes

Early diagnosis of hereditary cancer syndromes is critical to reducing cancer risk (1060)Mittendorf KF, et al. (2021) JCO Precis Oncol, 5. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. There are over 50 known hereditary cancer syndromes, but prevention testing remains underutilized due to cost, geographic location, and lack of awareness (1061)NCI Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Prevention and Early Detection for Hereditary Cancer Syndromes. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . To improve the availability and use of testing, many research projects, tools and initiatives have been developed to identify and improve care for individuals and families with hereditary cancer syndromes. For example, genetic testing using next‐generation sequencing technologies (e.g., companion diagnostics) to detect hereditary cancer syndromes is increasing in clinical settings. Many sponsor companies are developing cancer therapies in conjunction with companion diagnostics to identify individuals who are most likely to receive benefit from treatment and improve survival outcomes (1062)Cheng S, et al. (2012) N Biotechnol, 29: 682. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. To support early detection and treatment of hereditary cancer syndromes, it is critical to increase the accessibility of diagnostic testing for individuals and families at high-risk for cancer.

Policies to Address Disparities in Clinical Research and Care

Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers in Trial Design

There is growing awareness that diversity in cancer clinical trials is key to assessing differential efficacy of molecularly targeted therapeutics in various populations and maximizing the generalizability of treatment outcomes (1064). Despite stakeholder efforts to improve representation in cancer research, clinical studies do not reflect the racial and ethnic diversity of the US population. While the barriers to improve diverse representation in cancer research are complex, many can be addressed at the trial level (628)Oyer RA, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2163. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. FDA has published several guidance documents to improve clinical trial diversity during study design that address various topics including measures that increase diversity in clinical trials; post-marketing approaches to obtain safety and efficacy data for historically underrepresented populations; the modernization of eligibility criteria when scientifically appropriate; and the collection and analysis of racial and ethnic data. In January 2024, the agency issued guidance that outlines a standardized approach for collecting and reporting on race and ethnicity data in clinical trials (1065)US Food and Drug Administration. Collection of Race and Ethnicity Data in Clinical Trials and Clinical Studies for FDA-Regulated Medical Products Guidance for Industry. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . In the guidance, FDA recommends:

- study sponsors use a two-question format that asks for information about ethnicity before asking about race;

- avoiding the term “non-White” when collecting information on race and ethnicity;

- including more detailed race and ethnicity information for trials outside of the United States where these categories may not adequately describe racial and ethnic groups in other countries; and

- providing study participants with the opportunity to self-report their race and ethnicity.

The Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act (FDORA) was signed into law in December 2022 and outlines the need for greater diversity in clinical trials and authorizes the use of diversity action plans. Legislation within FDORA requires FDA to issue draft guidance for clinical study sponsors to develop a Race and Ethnicity Diversity Plan, which was published in April 2022. In addition to race and ethnicity, the plan recommends inclusion of other underrepresented populations based on sex, gender, age, socioeconomic status, disability, pregnancy and lactation status, and comorbidities. When designing clinical studies, the plan should include:

- a community engagement and patient outreach strategy;

- enrollment goals for diverse participation and the rationale for selecting those goals;

- the plan of action to enroll and retain diverse participants; and

- the status of meeting enrollment goals throughout the duration of the study.

FDA’s continuous efforts along with guidance documents and enactment of the DEPICT Act (H.R. 6584) in 2022 underscore the urgent need to improve the representativeness in clinical studies, but more is needed to holistically design equitable trials (1066)Russell ES, et al. (2023) J Clin Transl Sci, 7: e101. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](1067)Birhiray MN, et al. (2023) Blood Adv, 7: 1507. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Increasing diversity in genomic trials for targeted and immunotherapies, integrating the patient’s voice in the study protocol, and establishing meaningful community partnerships will achieve long-lasting progress in addressing cancer disparities (1068)Peters U, et al. (2023) Ther Innov Regul Sci, 57: 186. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers for Patients

There are many challenges to recruit and retain diverse volunteers to participate in cancer clinical studies. Many factors impede clinical study participation, including access, awareness, fear and distrust, which disproportionately impact certain groups depending on age, race/ethnicity, gender, geographic location, disease burden, and socioeconomic status (607)Reopell L, et al. (2023) PLoS One, 18: e0281940. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. These multidimensional barriers affect an individual’s capacity to participate in clinical studies.

Limited access to clinical research and health care is a major barrier to recruit and retain a diverse set of study participants, which can be attributed to lack of transportation, caregiver burden, employment, and financial constraints (607)Reopell L, et al. (2023) PLoS One, 18: e0281940. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, clinical research sites are often located in areas that are far from potential participants, particularly in rural communities (601)NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health. Review of the Literature: Primary Barriers and Facilitators to Participation in Clinical Research. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . The Improving Access to Health Care in Rural and Underserved Areas Act (H.R. 7383) introduced in 2022 calls for increased funding to expand access to care in rural communities by establishing a 5-year pilot program that increases capacity through enhanced training and clinical support for primary care providers. Focused structural solutions including decentralization of clinical studies, reimbursing for costs associated with trial participation, and extending clinic hours are needed to increase the availability and accessibility of cancer clinical trials (1070)Keegan G, et al. (2023) Surg Oncol Clin N Am, 32: 221. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

Lack of awareness and knowledge of clinical studies limits participation in cancer studies. Most study participants learn about clinical trials through their primary care provider, but research has shown that many underrepresented groups do not have a routine source of care (1071)Parast L, et al. (2022) J Gen Intern Med, 37: 49. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE] due to disproportionately fewer primary care clinics within racial and ethnic communities (1072)Brown LE, et al. (2012) West J Emerg Med, 13: 410. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Communities historically underrepresented in clinical trials may benefit from tailored educational campaigns to increase their awareness of clinical trials and encourage informed decision-making, which can include culturally adapted materials and engaging informational videos (180)Nouvini R, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128: 3860. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. FDA’s Enhance Equity Initiative and Project Community encourage increased communication between underserved populations and health care professionals to foster understanding, reduce cancer risk, and increase survival (1073)US Food and Drug Administration. Project Community. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Effective and intentional recruitment strategies are crucial to improve representation in clinical studies. Additional legislation to implement solutions that address patient barriers is needed to improve equitable clinical trial enrollment. Only through a coalition of patients, community stakeholders, academia, policymakers, industry, and nonprofit organizations can there be indelible progress to build a clinical trial ecosystem that represents real-world patients.

Improving Access to High-quality Cancer Care

Proper insurance coverage is vital to accessing high-quality cancer care. Over the past 15 years, the United States has made enormous strides in expanding insurance coverage. Following enactment of the ACA in 2009, the uninsured rate has declined from 17.8 percent in 2010 to 9.6 percent in 2022. This historic expansion in coverage was made possible by the creation of state-based and federal insurance marketplaces that offered new competitive markets for consumers to shop for commercial insurance plans, as well as incentives that have expanded Medicaid coverage to 41 states and the District of Columbia. Medicaid expansion has been especially crucial in addressing health disparities, as Medicaid remains a major source of coverage for patients from racial and ethnic minority groups. In Medicaid expansion states, rates of insured individuals have increased among Black, Hispanic, and rural populations compared to their counterparts in non-expansion states. Furthermore, Medicaid expansion has been connected to earlier diagnoses, more prompt treatment, and a higher number of treatment options for patients with cancer (1075)Hotca A, et al. (2023) Curr Oncol, 30: 6362. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. The Biden administration has also taken steps to roll back guidelines on work requirements in Medicaid, which has the potential to reserve coverage losses in states that initially implemented work requirements. Known for their complex administration and documentation requirements, Medicaid work requirements disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minorities. However, efforts remain underway to pursue work requirements in several states like Idaho, Louisiana, and South Dakota.

Despite historic gains in coverage through ACA marketplaces and Medicaid expansion, coverage challenges remain, particularly for vulnerable communities. For many Americans with low-quality insurance coverage, high premiums and high out-of-pocket costs make health care services unaffordable. According to the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 46 percent of respondents reportedly delayed or skipped care due to high costs (1076)The Commonwealth Fund. State of U.S. Health Insurance in 2022: Biennial Survey. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Geographic disparities on forgone care are particularly prevalent. A 2023 study found one in four rural cancer survivors in seven Appalachian counties in North Carolina reported delayed or missed medical treatment due to high cost, with rates nearing 50 percent among survivors aged greater than 65 years (1077)Falk DS, et al. (2023) Cancer Surviv Res Care, 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This trend is especially concerning given the strong link between delayed cancer treatment and higher mortality rates (1078)Hanna TP, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). Volume 3712020. p m4087. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE].

The resumption of the Medicaid redetermination process also threatens to exacerbate existing health disparities. Initially paused due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicaid determination refers to the process by which state Medicaid offices determine whether current Medicaid enrollees are still eligible for coverage (1079)KFF. 10 Things to Know About the Unwinding of the Medicaid Continuous Enrollment Provision. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . However, over seven million people have lost Medicaid coverage since states began to resume redeterminations in April 2023 (1080)KFF. Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker – Overview. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Many of these coverage losses were due to procedural reasons (1081)The Commonwealth Fund. Almost 3.8 Million People Lost Medicaid Coverage Since End of PHE. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , which prompted the Biden administration to pause Medicaid redetermination in 30 states (1082)Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Coverage for Half a Million Children and Families Will Be Reinstated Thanks to HHS’ Swift Action. Accessed: March 17, 2024. and subsequently issue new flexibilities for state Medicaid offices to limit coverage losses (1083)Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HHS Takes Additional Action to Keep People Covered as States Resume Medicaid, CHIP Renewals. Accessed: March 17, 2024. .

Special types of health care facilities such as safety net hospitals are also vital to providing members of underserved communities access to cancer care, particularly residents of low-income and rural communities. Safety net hospitals are disproportionately more likely to face financial challenges due to the fact that their patients are more likely to be enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid, which have lower reimbursement than commercial insurance plans. Furthermore, safety net hospitals have higher levels of uncompensated care (1084)Third Way. Revitalizing Safety Net Hospitals: Protecting Low- Income Americans from Losing Access to Care. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , which refers to care for which a provider receives no payment from a patient or insurer (1085)American Hospital Association. Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . These financial challenges are the primary reason why nearly 70 rural hospitals have closed between 2018 and 2023. Additionally, the combination of a higher proportion of uninsured or underinsured patients means safety net hospitals experience lower quality of care measures (1086)Sarkar RR, et al. (2020) Cancer, 126: 4584. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Fortunately, higher levels of government assistance and guidance can help ensure that safety net hospitals have sufficient resources and tools to provide better cancer care to underserved communities. Specific policies that could provide more sufficient levels of support for safety net hospitals include increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates for hospitals with a higher proportion of Medicaid and uninsured patients and tying rate increases to quality metrics to incentivize higher-quality care.

Another challenge for safety net hospitals in rural areas is a shortage of health care practitioners. Despite being home to one-fifth of the US population, rural hospitals only contain 10 percent of the nation’s physicians (1087)American Hospital Association. Rural Hospital Closures Threaten Access Solutions to Preserve Care in Local Communities. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . For physician specialties involved in cancer treatment, shortages are particularly acute in rural areas. Since 2012, the proportion of radiation oncologists in rural areas declined from 16 to 13 percent due to a combination of rural physicians leaving the workforce and fewer new physicians opting to practice in rural areas (1088)American Society for Radiation Oncology. Radiation oncology workforce study indicates potential threat to rural cancer care access. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Additionally, less than 24 percent of hematology and medical oncology practices have sites in rural areas (1089)American Society of Clinical Oncology. Key Trends in Tracking Supply of and Demand for Oncologists. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Workforce shortages have long plagued rural areas due to the difficulty of recruiting clinicians.

Since physicians who train in rural areas are more likely to practice in rural areas (1090)American Medical Association. Recipe for more rural physicians: More exposure in residency training. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , one way to address the workforce shortage is to increase the number of Medicare-funded residency slots, thereby creating more slots that can be directed to rural hospitals (982)Rains J, et al. (2023) JAMA, 330: 968. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Additionally, expansion of a visa waiver program that requires foreign physicians to practice in medically underserved communities shows great promise in addressing rural health care workforce shortages (1091)The Center for American Progress. Immigrant Doctors Can Help Lower Physician Shortages in Rural America. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Another solution is to utilize telehealth services to connect rural patients with specialists located in urban or suburban areas (1092)Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. How to Improve Health Care in Rural Areas. Accessed: March 26, 2024. . To boost telehealth utilization in rural areas, lawmakers should consider policies that would increase access to high-speed broadband Internet (see Advocacy for Universal Access to High-speed Broadband Internet).

Sustainably Supporting Patient Navigators and Community Health Workers

Patient navigation is a strategy to address disparities in cancer detection, treatment, and outcomes in underrepresented populations (1093)Dixit N, et al. (2021) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 41: 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Patient navigators and community health workers can assist in alleviating the socioeconomic and structural barriers to clinical trial participation as discussed throughout this report. Since the first patient navigation program in the United States was created in 1990, many organizations have recognized the unique role of patient navigators and community health workers across the cancer care continuum (1093)Dixit N, et al. (2021) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 41: 1. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE](1094)Freeman HP (2012) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 21: 1614. . These programs have historically been supported by grants, but financial compensation continues to challenge their sustainability (1095)Pratt-Chapman ML, et al. (2021) Implement Sci Commun, 2: 141. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. In 2023, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized a rule to offer reimbursement for oncology patient navigation in its Calendar Year 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (1095)Pratt-Chapman ML, et al. (2021) Implement Sci Commun, 2: 141. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This means that certified patient navigators can now be directly reimbursed for services provided to patients. Continued investment in patient navigators and community health workers from the federal government is essential to reduce many logistical barriers that impact the provision of high-quality, patient-centered care for historically marginalized populations.

Advocacy for Universal Access to High-speed Broadband Internet

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated the use of telemedicine in many facets of health care, including cancer care. Patient access to high-speed broadband Internet is essential to telehealth utilization (1097)US Department of Human and Health Services. Access to internet and other telehealth resources. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , which has become significantly more prevalent in cancer care since the start of 2020 (1098)The ASCO Post. How Telemedicine Can Transform Clinical Research and Practice. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . Examples of telemedicine in oncologic care and clinical trials include remote monitoring devices such as wearable technology and video conferencing.

Unfortunately, significant disparities exist along racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic lines in accessing broadband Internet. Low-income areas are less likely to have reliable broadband access than high-income areas. When controlling for income, broadband access in majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods is lower than in majority White or Asian neighborhoods (1099)Li Y, et al. (2023) Public Health, 217: 205. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. Furthermore, rural residents are nearly 9 percent less likely to have broadband access than their urban and suburban counterparts.

Disparities in access to broadband represent a major technological barrier to cancer care and clinical trials that increasingly utilize telemedicine (1100)Tevaarwerk AJ, et al. (2021) JCO Oncol Pract, 17: e1318. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. This barrier threatens to exacerbate existing health disparities since underutilization of telemedicine is associated with higher mortality rates in oncologic care (1101)Basch E, et al. (2017) JAMA, 318: 197. [LINK NOT AVAILABLE]. With most cancer patients expressing their comfort with using telehealth in oncologic care (1102)American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Survivor Views: Telehealth and Clinical Trials. Accessed: March 17, 2024. , those without access to high-speed Internet risk receiving delayed or suboptimal cancer care.

To ensure all communities can benefit from cancer clinical trials in the new era of increased telehealth use, it is paramount to advocate for policies that will provide universal access to high-speed broadband Internet. Successful policy proposals must target the underlying issues behind limited access to broadband Internet, including a lack of infrastructure in low-density communities and a lack of competition among Internet service providers that result in higher prices for consumers (1103)Forbes. Millions Of Americans Are Still Missing Out On Broadband Access And Leaving Money On The Table—Here’s Why. Accessed: March 26, 2024. .

In recent years, Congress and the Biden administration have increased access to broadband Internet. Both the American Rescue Plan Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provide $25 billion and $65 billion, respectively, to expand broadband infrastructure and provide financial assistance for certain underserved households (1104)The White House. FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Over $25 Billion in American Rescue Plan Funding to Help Ensure Every American Has Access to High Speed, Affordable Internet. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . To help further efforts to achieve universal broadband, some bipartisan legislative proposals in the 118th Congress would boost investments in programs that subsidize broadband costs for rural Americans (1105)Congress.gov. S.3321 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Lowering Broadband Costs for Consumers Act of 2023. Accessed: March 17, 2024. and ensure that grants awarded to improve broadband infrastructure are not subject to taxation (1106)Congress.gov. S.341 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Broadband Grant Tax Treatment Act. Accessed: March 17, 2024. . These proposals to grow broadband infrastructure and assist underserved households with paying for the high cost of high-speed Internet have the potential to allow more patients with cancer from various communities and backgrounds to participate in an increasingly telehealth-driven oncologic care and clinical trial environment.

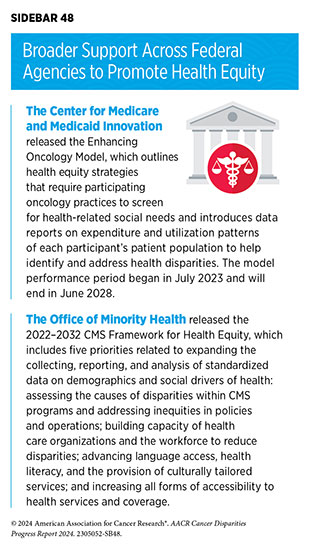

Coordination of Health Disparities Research and Programs Within the Federal Government

As described throughout this report, cancer disparities are caused by many intersecting social, economic, and environmental factors. There are several initiatives within the federal government that support multilayered interventions to reduce health disparities in cancer care (see Sidebar 48 and Understanding and Addressing Drivers of Cancer Disparities). To address the unequal burden of cancer and dismantle centuries of health care inequities, continued and deliberate investment in research and programs across all branches of government will be vital.

Next Section: Conclusion Previous Section: Overcoming Cancer Disparities Through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce