Executive Summary

This is an exciting time in cancer science and medicine. Thanks to research, we are making unprecedented progress against the many diseases we call cancer. More people than ever before are living longer and fuller lives after a cancer diagnosis. However, the grim reality is that advances against cancer have not benefited everyone equally. Because of a long history of structural inequities and systemic injustices in the United States (U.S.), certain segments of the U.S. population continue to shoulder a disproportionate burden of adverse health conditions, including cancer. The same socially, economically, and geographically disadvantaged populations have also experienced a greater negative impact from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Disparities in health care are among the most significant forms of inequity and injustice, and it is imperative that everyone play a role in eradicating the social injustices that are barriers to health equity, which is one of our most basic human rights.

As the first and largest professional organization in the world focused on the conquest of cancer whose core values include diversity, equity, and inclusion, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) is committed to accelerating the pace of research to address the disparities across the cancer continuum faced by racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations. It is also dedicated to increasing public understanding of cancer health disparities and the importance of cancer health disparities research for saving lives, and to advocating for increased annual federal funding for government entities that fuel progress against cancer health disparities, in particular, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022 to Congress and the American public is a cornerstone of AACR’s educational and advocacy efforts to achieve health equity. The report highlights areas of recent progress in reducing cancer health disparities. It also emphasizes the vital need for continued transformative research and for increased collaborations among all stakeholders working toward the bold vision of health equity if we are to ensure that research-driven advances benefit all people, regardless of their race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or geographic location.

The State of Cancer Health Disparities in 2022

In the United States, we have experienced tremendous progress against cancer in recent decades. As a result, overall cancer incidence and mortality are declining steadily across all population groups. Further encouraging is the evidence that the differences in overall cancer incidence and death rates are decreasing between racial and ethnic groups.

Despite these encouraging trends, disparities across the cancer continuum remain a major public health challenge in the United States. Compared to the White population, racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations continue to share a disproportionate burden for certain types of cancer. As one example, although disparity in cancer-related deaths between Black and White populations has been narrowing, the Black population still has the highest rate of overall cancer mortality. Other racial and ethnic minorities continue to experience disproportionate burden for certain types of cancer. Similarly, those living under persistent poverty or in rural areas continue to face serious structural barriers and/or systemic inequities in their access to quality health care.

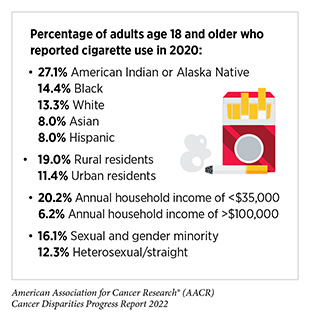

A long history of racism in the United States has resulted in discriminatory policies, systemic inequities, and structural barriers that cause and perpetuate cancer health disparities. Researchers are using a framework of interrelated and overlapping factors, called social determinants of health (SDOH), to understand and address cancer health disparities. Among the key SDOH are socioeconomic factors such as education and income; modifiable factors such as tobacco use and physical inactivity; psychological factors such as stress and mental health; environmental factors such as housing and transportation; health care access and experiences; and biological and genetic factors. SDOH operate at individual, community, and population levels to drive health outcomes.

Cancer health disparities not only adversely affect the lives of millions of Americans, but they also carry an immense economic toll. According to one estimate examining the direct cost of cancer health disparities during 2002-2007, eliminating racial disparities in incidence of the four most common types of cancer—lung, colorectal, breast, and prostate—would have resulted in $2.3 billion in savings in annual medical expenditures by patients with cancer. Another study found that, compared to White individuals, the rate of lost earnings for Black individuals was more than double because of premature deaths related to prostate and stomach cancers and multiple myeloma.

Given the significant personal, societal, and economic impact of cancer health disparities, there is an increased urgency within the cancer community to understand and address cancer health disparities. It is increasingly evident that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many of the existing cancer health disparities. Therefore, funding research to understand and address the public health challenge of cancer health disparities is a vital national investment to achieve an equitable future for all populations.

Understanding Cancer Development in the Context of Cancer Health Disparities

Understanding the hallmarks that define how cancer develops has increased tremendously in the past two decades, thanks to major advances in medical research. We now know that cancer is not a single disease but a collection of disorders broadly characterized by the inability of a cell to respond to normal biological cues related to cell division, growth, and death.

Cancer development occurs through fundamental changes to the genetic material inside the cell, as well as in the surrounding cellular and molecular environment. Reciprocal interactions between the cancer cell and the tumor microenvironment—cells, molecules, and blood vessels that surround a cancer cell—influence tumor progression and spread into other tissues, a process called metastasis. Gaining an understanding of the changes that occur internally and externally and how these changes drive cancer initiation and progression is essential for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and development of effective treatments.

Historically, research studies on the genetic and microenvironmental changes of the tumor have been performed primarily in individuals of European ancestry. Lack of representation in these studies of racial and ethnic minorities and other underrepresented groups has severely limited our understanding of genetic predispositions that lead to higher incidence and mortality or increased aggressiveness of cancer in these individuals. Identification of alterations that lead to cancer using diverse laboratory research models while creating large and inclusive databases will increase our knowledge surrounding the cancer-related genetic, epigenetic, and other changes that occur in patients from different ancestral groups. As one example, recent data show that the frequency of alterations in the EGFR gene differs based on ancestry of the patient, with the highest rates of alteration observed in East Asian groups and the lowest rates observed in patients of African and European descent. Many initiatives such as the NIH’s All of US Research Program or AACR Project GENIE® are beginning to shed light on different genetic changes associated with cancer in different racial and ethnic populations, but there is an urgent need to significantly increase research into this important factor influencing cancer health disparities.

Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Cancer Risk Factors

Decades of research have led to the identification of numerous factors that increase a person’s risk of developing cancer. Many of these factors, which are often referred to as cancer risk factors, are potentially modifiable. In the United States, the major potentially modifiable cancer risk factors are tobacco use; obesity; lack of physical activity; alcohol consumption; exposure to UV light from the sun or tanning devices; infection with certain pathogens, such as cancer-causing strains of human papillomavirus (HPV), and environmental exposure to carcinogens.

Individuals can reduce their risk of developing certain types of cancer through behavioral changes. However, long-standing inequities in numerous SDOH contribute to significant disparities in the burden of preventable cancer risk factors among socially, economically, and geographically disadvantaged populations. These disparities stem from a long history of structural, social, and institutional injustices, and not only place disadvantaged populations in unfavorable living environments (e.g., with higher exposure to environmental carcinogens), but also contribute to their increased risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption, or unhealthy diet).

It must be noted that an individual’s behavior and exposures are strongly influenced by the individual’s living environment. For example, lack of quality housing may expose residents, such as those living in disadvantaged communities without comprehensive smoke-free policies, to high levels of secondhand smoke, a known risk factor for lung cancer. Moreover, disadvantaged populations may not be able maintain behaviors that are key to lowering cancer risks, such as maintaining a healthy weight, eating a healthful diet, and being physically active, because of factors beyond their control, e.g., the unavailability of healthy food options and/or lack of safe greenways and parks for recreation and physical activity in the neighborhood. It is also important to note that socioeconomic and geographic disadvantages intersect with other population characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and disability status. It is imperative that public health experts prioritize cancer prevention efforts that account for the complex and interrelated factors at institutional, social, and individual levels, all of which influence personal risk behavior and disparate health outcomes.

Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection

The aim of cancer screening is to find precancerous lesions and cancers at their earliest possible stage when it is easier to treat them successfully. In United States, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), as well as other professional societies, carefully weighs benefits and potential harms of screening for certain types of cancer to issue population-level screening guidelines. USPSTF recommends that individuals who are at an average risk of developing cancer should receive screening for breast, prostate, cervical, and colorectal cancers. USPSTF also issues guidelines for certain individuals who should be screened for other types of cancer only if they are at an increased risk of developing these cancers; e.g., current or former smokers should be screened for lung cancer.

Routine cancer screening is one of the most effective ways to reduce the burden of cancer at the population level. Yet, many disparities in cancer screening exist for racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations. Some of these disparities are a result of screening guidelines that are based on studies with predominantly White participants. USPSTF and other cancer-focused professional organizations routinely evaluate newly available evidence and adjust their guidelines accordingly. Some cancer screening disparities stem from systemic and structural barriers. For example, residents who live in remote areas have less access to health care facilities with capabilities to perform certain cancer screening tests. Yet, some other disparities in cancer screening exist because of the deeply rooted mistrust of the health care system. Cultural beliefs as well as lack of knowledge about cancer screening also play a role in cultivating disparities in cancer screening. Another source of disparities is the lack of follow-up exam(s) if the initial cancer screening test indicates that the individual may have cancer.

Researchers are taking innovative and multipronged approaches to raise awareness and increase knowledge of the importance of cancer screening among racial and ethnic minorities. Many approaches have been successfully applied at local or state levels and provide a blueprint to effectively reach racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations across the nation for increased adherence and follow-up to cancer screening. These strategies include developing comprehensive public health campaigns that not only raise the awareness, but also make it easier for eligible individuals to adhere to cancer screening; increasing access to health insurance to minimize out-of-pocket costs for certain types of screening tests; developing culturally tailored interventions through community engagement to alleviate any concerns about cancer screening in a culturally sensitive manner; reducing structural barriers by providing at-home screening tests where possible; and reducing mistrust in the health care system by improving communications between patients and providers.

Disparities in Clinical Research and Cancer Treatment

Researchers working across the continuum of cancer science and medicine are constantly powering the translation of new discoveries into advances in cancer treatment that are improving survival and quality of life for U.S. adults and children. Clinical trials are a vital part of medical research because they establish whether new cancer treatments are safe and effective. Therefore, it is imperative that participants in clinical trials testing new cancer treatments represent all population groups who may use these therapeutics if they are approved. Despite this knowledge, enrollment in cancer clinical trials is extremely low, and there is a serious lack of sociodemographic diversity among those who do participate. Recent data indicate that community outreach and patient navigation can enhance participation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials. It is vital that all stakeholders in the medical research community work together to identify interventions which ensure equitable participation of all population groups in clinical studies since is the only way to guarantee that all segments of the U.S. population benefit from the unprecedented advances against cancer.

Most patients with cancer are treated with a combination of treatment options across the five pillars of cancer treatment— surgery, radiotherapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy, molecularly targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Despite major advances in these treatments in recent years, racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations frequently experience severe and multilevel barriers to quality cancer treatment, including delays in or lack of access to standard of care treatments, as well as higher rates of treatment-related financial toxicities. Many patients from disadvantaged population groups also experience overt discrimination and/or implicit bias during the receipt of care.

Encouragingly, recent data show that racial and ethnic disparities in cancer outcomes can be eliminated if every patient has equitable access to standard of care treatments. In fact, researchers have shown that racial and ethnic minority patients respond better to treatments against many cancers compared to White patients, and have better outcomes when offered similar access to standard and quality care. Therefore, it is imperative that all sectors work together to address the challenges of disparities in cancer treatment, a necessity to achieve health equity. In this regard, it should be noted that several clinical studies, including the Accountability for Cancer through Undoing Racism and Equity (ACCURE) program, have shown that multilevel interventions that utilize patient navigation can address the current disparities in cancer treatment and also improve outcomes for all patients.

Disparities in Cancer Survivorship

Any person who has been diagnosed with cancer may be referred to as a cancer survivor from the time of initial diagnosis until the end of life. As more people are living longer and fuller lives after a cancer diagnosis—thanks to improved detection and treatment options—greater attention is needed to understand the survivorship experience. While every cancer survivor has a unique experience, those belonging to medically underserved populations shoulder a disproportionate burden of the adverse effects of cancer survivorship. Understanding the challenges faced by these groups will help inform cancer care strategies and personalized recommendations to support those who are more vulnerable and lead to better quality of life.

Cancer treatments can be difficult for a patient’s physical and mental health, and can contribute to potentially adverse side effects during or after cessation of treatment. Individuals from racial and ethnic minorities and other medically underserved populations have been shown to experience side effects at higher rates than those who are White. The adverse physical effects, coupled with worsened functional, psychological, social, and financial challenges, contribute to inferior health-related quality of life, an increasingly important consideration in cancer care, drug approvals, and long-term survival predictions. It has long been recognized that health-related quality of life is lower in cancer survivors compared to individuals who have never had a cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, cancer survivors from medically underserved groups are at an increased risk of experiencing worse health-related quality of life.

A major contributing factor to poor health-related quality of life is financial toxicity, which refers to the detrimental effects experienced by cancer survivors and their family members caused by the financial strain after a cancer diagnosis. Out-of-pocket costs for cancer care are higher than any other illness and often result in coping behaviors, such as skipping medications and follow-up visits, and/or taking on debt. Financial toxicity is more prevalent in individuals from disadvantaged groups such as those from low socioeconomic status, further exacerbating their poverty.

A key to charting an equitable path forward for cancer survivors who belong to medically underserved populations is the use of community-based and culturally tailored solutions that meet the specific needs of the patient and the particular population group. These interventions include involving patient advocates and patient navigators as key partners and addressing the specific social, psychological, medical, and physical needs of the patient while taking into account cultural norms and perceptions. Such comprehensive approaches will ultimately lead to increasing quality of life; bolstering adherence to follow-up care; identifying financial concerns; providing equitable health care; and reducing the overall cost of cancer care.

Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities Through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce

Diversity can be defined as the full range of human similarities and differences in group affiliation including gender, race and ethnicity, social class, role within an organization, age, religion, sexual orientation, physical ability, and other group identities. The overall health care workforce has become more diverse in recent years. However, representation of racial, ethnic, sexual, and gender minorities in the cancer research and care workforce has not kept pace with trends in the U.S. population and contributes to cancer health disparities. A key strategy to eliminate cancer health disparities and achieve health equity is to increase diversity along the science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine training pipeline and support the entire cancer research and care workforce. A diverse cancer research and care workforce would enhance the quality of care; improve patient satisfaction; strengthen trust in the medical research community; increase enrollment in clinical trials of underrepresented and underserved community members; and expand access to jobs in health care. Continued, intentional efforts to increase diversity across the cancer care and research workforce are needed to achieve health equity.

Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities Through Science-based Public Policy

Strong public health policies have contributed to the progress that has been made in reducing cancer health disparities over the past two decades. Evidence-based public policies have the potential to address disparities by improving prevention and early detection of cancers, improving diversity in clinical trial enrollment, increasing access to health care for racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations, and improving the quality of care they receive.

Improved tobacco control regulations, such as prohibiting menthol cigarettes and improving smoking cessation support, especially among the racial and ethnic minorities and other disadvantaged groups who are specifically targeted by the tobacco industry through advertisements, could greatly reduce disparities in tobacco-related illnesses. Legislation to increase awareness of HPV vaccination and cancer screening could decrease disparities in cancer incidence and mortality, and eliminate cervical cancer in the United States. It is evident that a complex interplay between social and environmental factors drives cancer health disparities. This interaction provides several opportunities for implementing policies to prioritize environmental justice, cancer equity research, and improved access to cancer care. Federal support of collaborative initiatives with academic institution- and community-based organizations has resulted in strengthening equitable partnerships at the community level. Continued meaningful collaborations across all branches of government are needed to address the health care needs of historically underserved groups and improve cancer outcomes for all populations.

AACR Call to Action

Systemic inequities and social injustices have adversely impacted every aspect of cancer research and patient care, including limited participation in clinical trials and differences in cancer incidence and outcomes among underserved populations. In addition, these inequities have created barriers to career advancement for underrepresented minorities. While new research and initiatives are closing these gaps, progress has been slow, and the cost of cancer health disparities remains monumental. To reduce cancer health disparities, the structural barriers that lead to these outcomes must be rectified.

Therefore, AACR calls on policy makers and other stakeholders committed to eliminating cancer health disparities to:

- Provide robust, sustained, and predictable funding increases for the federal agencies and programs that are tasked with reducing cancer health disparities, including the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Ensure that cancer-related, disaggregated data are collected and analyzed for sexual, gender, racial, and ethnic minority populations.

- Improve representation in clinical trials by reducing barriers to patient enrollment and requiring enhanced data reporting and community engagement, as included in the Diverse and Equitable Participation in Clinical Trials (DEPICT) Act.

- Prioritize cancer control initiatives, including increased HPV vaccination and awareness, and improved access to cancer screening.

- • Expand Medicaid and access to quality, affordable health care coverage, and provide greater support for patients and health care providers.

- Implement concrete steps to increase diversity in the cancer research and care workforce.

- Enact provisions of the Health Equity and Accountability Act (HEAA), comprehensive legislation that aims to eliminate racial and ethnic health inequities.

AACR has been a pioneer and a leader in advancing the science of cancer health disparities with the goal of eliminating cancer health disparities. We are proud to share the latest effort, the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2022, to achieve this important goal. The second edition of the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report builds on the inaugural report released in 2020, which brought to the forefront many of the key actions needed to overcome the enormous public health challenges posed by cancer health disparities. Fulfilling the recommendations included in our Call to Action demands ongoing and active participation from a broad spectrum of stakeholders. These efforts must be coupled with actions to eradicate the systemic inequities and social injustices that are barriers to health equity, which is one of our most basic human rights. This is why AACR stands in solidarity against racism, privilege, and discrimination in all aspects of life and actively supports policies that guarantee equitable access to quality health care and thereby eradicate all barriers to achieving the bold vision of health equity.