- Importance of Cancer Screening and Follow-up Care

- Guidelines for Cancer Screening

- Eligibility Criteria for Cancer Screening

- Recommendations for Cancer Screening

- Tests for Cancer Screening

- Spotlight: Genetic Testing and Surveillance in Children with Cancer Predisposition

- Suboptimal Uptake of Cancer Screening

- Emerging Technologies for Early Detection of Cancer

Screening for Early Detection

In this section, you will learn:

- Cancer screening aims to detect cancer or abnormal cells that may become cancerous in people without any signs of the disease.

- The United States Preventive Services Task Force, a panel of experts in preventive medicine, periodically issues evidence-based screening recommendations for cancers of breast, cervix, colon and rectum, lung and bronchus, and prostate.

- Cancer screening is a multistep process that includes receiving the recommended test, as well as follow-up care if the initial test shows abnormal findings.

- Disadvantaged segments of the US population experience disparities in the recommended cancer screening and follow-up care.

- Evidence-based interventions are proving effective in increasing adherence to recommended cancer screening guidelines.

- Researchers are cautiously optimistic about the potential of artificial intelligence and minimally invasive screening tests in detecting cancers early.

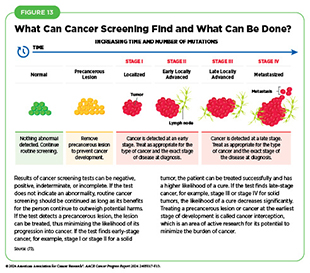

Cancer screening is the systematic process of checking for cancer or for abnormal cells that may become cancerous before a person has any signs or symptoms of the disease. The purpose of cancer screening is to detect aberrations at the earliest possible stage of cancer development. When detected early, cancer may require less aggressive treatments and may be curable. For instance, early-stage cancers are typically smaller, have not spread to other parts of the body, and can sometimes be removed completely with surgery. In contrast, cancers detected at later stages may require more complex treatments, which may be less effective and with significant side effects (see Figure 13).

Importance of Cancer Screening and Follow-up Care

The overarching goal of cancer screening is to reduce the burden of the disease in the general population. Several recent studies have shown that certain forms of cancer screening can reduce deaths from specific types of cancer. Findings from a study of patients at increased risk for lung cancer showed that screening resulted in 21 percent and 39 percent reductions in deaths from any cause and from lung cancer, respectively (398)Edwards DM, et al. (2024) Cancer, 00: 1. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.35340.. The reduction in breast cancer–related deaths in the past five decades is yet another example underscoring the importance of routine

screening. A recent study reported that breast cancer mortality in the United States per 100,000 women has declined from 48 deaths in 1975 to 27 deaths in 2019 (399)Caswell-Jin JL, et al. (2024) JAMA, 331: 233. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.25881.. Projections from the study showed that 25 percent of this reduction was attributable to breast cancer screening (399)Caswell-Jin JL, et al. (2024) JAMA, 331: 233. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.25881.. Another study evaluating benefits of adhering to cancer screening recommendations issued by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (see Guidelines for Cancer Screening) projected that just a 10-percentage point increase in adherence could prevent an estimated 15,580 additional deaths from lung, colorectal, breast, and cervical cancers combined (400)Knudsen AB, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2344698. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44698..

Cancer screening also reduces the likelihood of developing advanced-stage cancer. In a county-level population-based ecological study, researchers evaluated the impact of prostate cancer screening on the likelihood of developing advanced-stage prostate cancer. The analysis included nearly half a million responses from all US counties that were captured by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a system of telephone surveys conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to collect and collate state-level health data of US residents. Researchers found that US counties with higher rates of prostate cancer screening between 2004 and 2012 had lower incidence of advanced-stage prostate cancer and lower number of deaths from prostate cancer (402)Stone BV, et al. (2024) Eur Urol Oncol, 7: 563. DOI: 10.1016/j.euo.2023.11.020.. Findings show that a 10 percent higher probability of prostate cancer screening at the county level between 2004 and 2012 was associated with a 14 percent lower incidence of advanced-stage prostate cancer between 2015 and 2019, and with a 10 percent lower risk for prostate cancer mortality between 2016 and 2020 (402)Stone BV, et al. (2024) Eur Urol Oncol, 7: 563. DOI: 10.1016/j.euo.2023.11.020..

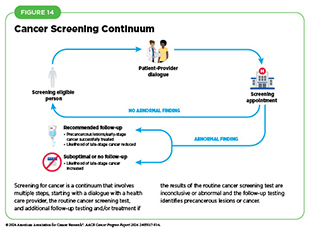

It is important to note that cancer screening is a continuum involving a series of tasks and steps (see Figure 14). For individuals who are eligible for cancer screening, the process begins with a dialogue between individuals and their health care provider about the benefits and harms of cancer screening based on risk factors specific to them, such as a family history of cancer (see Eligibility Criteria for Cancer Screening). If the initial recommended screening test indicates no abnormality, no action is needed until the next time the routine cancer screening is due. However, if the initial recommended screening test identifies precancerous lesions or presence of cancer or shows inconclusive results, follow-up care may be necessary, and the future course of action should be determined in consultation with the health care provider. For example, additional tests may be necessary to confirm initial findings, as well as to diagnose the cancer stage. Health care providers may use this information to recommend a course of treatment, ranging from surgical removal of precancerous lesions or cancer to treatment with anticancer drugs.

Unfortunately, many people do not follow up after the initial screening even when the findings indicate an abnormality (404)Doubeni CA, et al. (2018) CA Cancer J Clin, 68: 199. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21452.. The reasons for suboptimal follow-up care include structural and systemic barriers, lack of transportation, not being able to take time off from work, and lack of health insurance. It is critical that people establish a regular dialogue with their health care providers about routine cancer screenings, as well as about follow-up care plans if initial findings indicate that cancer may be present. Patient navigators can be especially helpful in ensuring high degrees of follow-up by overcoming common barriers to care.

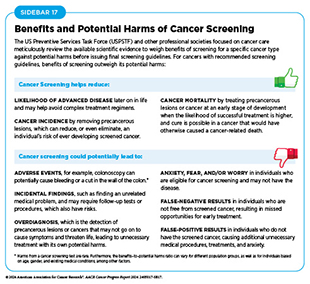

It is also important to recognize that while the benefits of routine cancer screening are many, cancer screening is a medical procedure and does carry potential harms (see Sidebar 17). Experts carefully consider the risks and benefits of cancer screening when developing the recommendations (see Guidelines for Cancer Screening). Dialogue between providers and patients, as well as easily available and understandable information, about the benefits and potential harms of cancer screening can play a pivotal role for people in making an informed decision about cancer screening.

Guidelines for Cancer Screening

Panels of subject matter experts, convened by government agencies and some professional societies focused on public health, develop evidence-based recommendations for cancer screening through a careful and meticulous process. This report focuses on screening recommendations developed and issued by USPSTF, which is a congressionally mandated independent panel of experts and is convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the US Department of Health and Human Services. USPSTF is charged with making evidence-based recommendations that can be used in primary care settings to prevent disease, including cancer. USPSTF uses a multistep process that includes a careful review of the available evidence on the topic and engagement of the scientific community and the public before issuing the final recommendations. There are some differences in the process used by different organizations, but all organizations aim for the same rigor to ensure maximal benefit and minimal harm to public health.

Eligibility Criteria for Cancer Screening

Population-level cancer screening guidelines are developed based on a person’s lifetime risk of developing cancer. People without a family history or personal history of cancer, and without an inherited genetic condition that may cause cancer, are at an average risk of being diagnosed with the disease. Two key considerations for recommending screening in average-risk individuals are sex assigned at birth and age. People with a strong family history or a personal history of cancer, certain tissue makeup, an inherited genetic condition, or exposure to one or more cancer risk factors are at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer. One example is individuals who smoke, which significantly increases their likelihood of developing lung cancer and dying from it (see Eliminate Tobacco Use).

Women with extremely dense breast tissue are considered at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer. Having dense breast tissue is not abnormal, but it is one of the risk factors for developing breast cancer (405)Bodewes FTH, et al. (2022) Breast, 66: 62. DOI: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.09.007..

Furthermore, dense breast tissue, which appears white on a mammogram, can mask tumors, making it more challenging to detect cancer early.

People with hereditary cancer syndromes are at a higher-than-average risk of being diagnosed with cancer because of the genetic mutations they carry, which predispose them to certain types of cancer (see Figure 6). For example, von Hippel–Lindau syndrome is caused by mutations in the VHL gene, which is important for regulating cellular processes in response to changes in oxygen levels within cells. People who have von Hippel–Lindau syndrome are at an increased risk of developing cancers of the kidney and brain and other parts of the nervous system. Experts recommend genetic testing and counseling for those with a hereditary cancer syndrome, including for children (see Genetic Testing and Surveillance in Children With Cancer Predisposition).

Some of the factors used to determine eligibility for cancer screening, such as exposure to cancer risk factors, are different for each person and may change throughout life. It is also noteworthy that cancer screening is a process and not a single test or scan (see Figure 14). It is important that people stay abreast of the most up-to-date information on cancer screening through an ongoing dialogue with their health care providers and develop a personalized cancer screening plan that considers their specific risks and tolerance of potential harms from screening tests.

Recommendations for Cancer Screening

USPSTF issues recommendations for screening for certain cancer types when the evidence indicates that the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harm, recommendations against screening for certain cancer types when the evidence indicates that the potential harm from screening outweighs benefits, as well as informs if there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation for certain cancer types. For example, USPSTF recently concluded that the current evidence was insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of visual skin examination by a clinician to screen for skin cancer in adolescents and adults (406)United States Preventive Services Taskforce (2023) JAMA, 329: 1290. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.4342.. Based on confidence in the available evidence, USPSTF assigns a grade to its final recommendations; the grade determines which services are covered without out-of-pocket costs under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). USPSTF can also assign different grades to different population groups within the same cancer type (see Sidebar 18). The finalized recommendations and review of the scientific evidence used to develop recommendations are published in a scientific journal and on the USPSTF website.

USPSTF periodically revises its recommendations for cancer screening as new evidence becomes available. For example, in April 2024, USPSTF revised its recommendations for breast cancer screening to lower the age to start routine screening from 50 years to 40 years (407)United States Preventive Services Taskforce (2024) JAMA, 331: 1918. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2024.5534.. Furthermore, USPSTF did not find sufficient evidence to assess whether breast cancer screening for individuals 75 and older is beneficial or harmful, or whether those who have dense breasts and whose mammogram does not show any signs of cancer should undergo supplemental screening using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasonography (407)United States Preventive Services Taskforce (2024) JAMA, 331: 1918. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2024.5534..

The updated recommendations were based on 20 studies, including three randomized controlled screening trials, as well as on several modeling studies that also included race-specific breast cancer models for Black women, who have a 40 percent higher risk of death from breast cancer compared to White women (3,408). The revised recommendations apply to cisgender women and all other persons assigned female at birth, including transgender men and nonbinary persons (407)United States Preventive Services Taskforce (2024) JAMA, 331: 1918. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2024.5534.. The reduced starting age for breast cancer screening in the revised recommendations is estimated to save 19 percent more lives from breast cancer (407)United States Preventive Services Taskforce (2024) JAMA, 331: 1918. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2024.5534.(409)United States Preventive Services Taskforce. Draft Recommendation: Breast Cancer: Screening. Accessed: July 5, 2023..

Researchers are continually working to improve cancer screening, with the ultimate goal of maximizing benefits from screening while minimizing potential harms. For example, a recent study reported that for those who do not have a family history of colorectal cancer and whose first colonoscopy did not show any signs of colorectal precancerous lesions or cancer, the interval between colonoscopy screenings can be extended from 10 years to 15 years without compromising the benefits of colorectal screening (410)Liang Q, et al. (2024) JAMA Oncol, 00: e240827. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.0827.. These findings have the potential to reduce any adverse events as well as anxiety associated with colonoscopy. Another study found that the risk of developing cervical precancerous lesions at 8 years after a negative human papillomavirus (HPV) screening test was comparable to the risk at 3 years after a negative cytology screening, which is the current standard for acceptable risk (411)Gottschlich A, et al. (2024) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 33: 904.. The findings suggest that primary screening intervals for HPV detection may be extended safely beyond the current 5-year recommendation.

Tests for Cancer Screening

When developing cancer screening recommendations, USPSTF also recommends which tests should be used for different types of cancer. This information is gleaned from the available scientific evidence, and USPSTF carefully weighs the benefits and potential harms of different tests before making a final recommendation.

There are different kinds of cancer screening tests that include laboratory tests to determine the changes in cancer biomarkers in biospecimen samples, and imaging or endoscopic procedures to look for specific abnormalities (see Sidebar 19).

Sometimes, additional tests beyond USPSTF recommended tests may be used based on particular situations as determined by the health care provider. For example, breast MRI is not a USPSTF-recommended test and is not typically used to screen for breast cancer. However, a breast MRI may be performed to further evaluate abnormal findings on mammograms for persons with dense breast tissue, which makes it hard to see abnormal areas on mammography (412)Hussein H, et al. (2023) Radiology, 306: e221785. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.221785.. Furthermore, researchers continually evaluate the safety and accuracy of new and improved methods. For example, findings from a recent study showed that colorectal cancer screening based on a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) that detects three proteins in a stool sample was predicted to decrease colorectal cancer incidence by 5 percent and associated deaths by 4 percent, compared to screening based on the current standard FIT, which detects only one protein in stool sample (413)Wisse PHA, et al. (2024) Lancet Oncol, 25: 326. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00651-4..

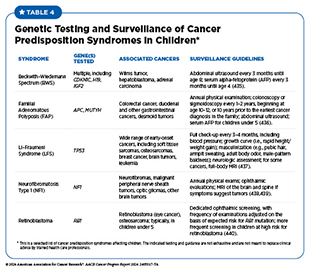

Genetic Testing and Surveillance in Children With Cancer Predisposition

Childhood cancers are considered rare and constitute less than 1 percent of all new cancer diagnoses each year, but they are the second leading cause of death and the leading cause of disease-related death in children (414)Scollon S, et al. (2017) J Genet Couns, 26: 387. DOI: 10.1007/s10897-017-0077-8.. Advances in genetic sequencing have revealed that about 10 percent to 15 percent of all childhood cancers are attributable to inherited genetic mutations that predispose children to the risk of developing certain types of cancer (154,155,157). Genetic testing and surveillance can provide a proactive approach to monitoring and managing cancer risk in children with a known predisposition to cancer. One modeling study evaluated the benefit of universal population-based genetic testing of newborns for cancer predisposition syndrome (415)Yeh JM, et al. (2021) Genet Med, 23: 1366. DOI: 10.1038/s41436-021-01124-x.. The model estimated that, among a typical US birth cohort of 3.7 million newborns, 1,803 newborns would develop cancer before age 20. The model suggested that universal screening could identify 13.3 percent of newborns as at-risk, potentially resulting in a 7.8 percent decrease in cancer deaths before age 20 if these at-risk newborns are placed under surveillance (415)Yeh JM, et al. (2021) Genet Med, 23: 1366. DOI: 10.1038/s41436-021-01124-x..

Unlike recommendations for routine cancer screening in adults, cancer screening in children is more specialized and focuses on those who have hereditary cancer syndromes or show early signs or symptoms of cancer (416)Ripperger T, et al. (2017) Am J Med Genet A, 173: 1017. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38142. (see Table 4). In 2016, the American Association for Cancer Research® (AACR) convened the Childhood Cancer Predisposition Workshop, which issued its recommendations in 2017 in a series of articles for genetic testing and surveillance in children at risk of developing cancer (417)Brodeur GM, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e1.(418)Greer MC, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e6.(419)Porter CC, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e14.(420)Walsh MF, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e23.(421)Tabori U, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e32.(422)Kratz CP, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e38.(423)Evans DGR, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e46.(424)Evans DGR, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e54.(425)Foulkes WD, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e62.(426)Rednam SP, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e68.(427)Schultz KAP, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e76.(428)Villani A, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e83.(429)Druker H, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e91.(430)Kamihara J, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e98.(431)Achatz MI, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e107.(432)Kalish JM, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e115.(433)Wasserman JD, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e123.(434)Malkin D, et al. (2017) Clin Cancer Res, 23: e133.. These recommendations provide a comprehensive framework for monitoring and managing the risk of childhood cancer.

Genetic testing in children who are at a high risk of developing cancer has many advantages. For example, early identification of genetic predispositions can allow for regular monitoring and early intervention, and can significantly improve prognosis and survival rates. Furthermore, genetic testing can help develop tailored screening and prevention strategies, leading to more effective management of cancer risk. The knowledge of genetic risk also enables informed decisions about health management, preventive measures, and lifestyle changes (441)Kesserwan C, et al. (2016) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 35: 251. DOI: 10.1200/EDBK_160621..

It is important to note that genetic testing also carries potential drawbacks and challenges. The knowledge of a genetic predisposition to cancer can cause significant anxiety and stress for both the child and their family. Concerns about the child’s right to autonomy and the potential for genetic discrimination in insurance and employment are important ethical and legal considerations (442)Fallat ME, et al. (2013) Pediatrics, 131: 620. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-3680.. Moreover, genetic tests are not always definitive, and false positives or false negatives can lead to unnecessary interventions or a false sense of security (441)Kesserwan C, et al. (2016) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 35: 251. DOI: 10.1200/EDBK_160621..

Parents and health care providers should discuss the benefits and potential risks of genetic testing in children for cancer, especially if there is a family history of cancer. Early detection through appropriate genetic testing for cancer predisposition and subsequent surveillance can lead to better outcomes and more effective treatment strategies for childhood cancers.

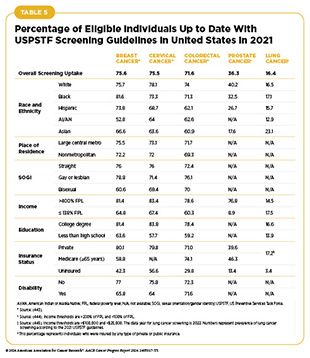

Suboptimal Uptake of Cancer Screening

Following the recommended cancer screening is one of the most important ways to reduce cancer burden at the population level. Unfortunately, adherence to cancer screening remains suboptimal. Furthermore, screening patterns vary for different types of cancer among racial and ethnic minority groups, citizens of sovereign Native Nations, and medically underserved populations (see Table 5). As detailed in the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024, there are several reasons for low rates of cancer screening and genetic testing, including social and structural barriers; bias and discrimination against marginalized populations in the health care system; mistrust of health care professionals among minoritized populations; lack of access to quality health insurance; low health literacy; and miscommunication between patients and providers (29)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024. Accessed: June 14, 2024..

It is important to fully understand whether suboptimal uptake of cancer screening and follow-up care contributes to higher burden of cancer in people belonging to certain population groups. One of the ways to improve cancer screening uptake is to deliver care that is tailored to specific populations and is designed to overcome systemic and structural barriers. Because certain populations have a higher risk of developing cancer, it is also important to develop screening guidelines and interventions that are based on data from the population for which the recommendations have been issued.

Progress Toward Increasing Adherence to Cancer Screening Guidelines

Multilevel and multipronged approaches are required to eliminate cancer inequities across the continuum of care, including improved uptake and follow-up of recommended evidence-based cancer screening among all eligible individuals. Stakeholders across the cancer care continuum are working together to achieve these goals. As detailed in the AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024, several evidence-based approaches have shown promising outcomes in increasing awareness and uptake of routine cancer screening and follow-up care, as well as in reducing inequities in cancer screening (29)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024. Accessed: June 14, 2024..

The Community Guide, an evidence-based set of guidelines developed by the Community Preventive Services Task Force, recommends several approaches for both patients and providers to increasing cancer screening. These approaches include engaging community health workers; implementing multilevel interventions, such as increasing literacy about cancer screening and reducing structural barriers to cancer screening; and instituting patient navigation services. In addition, researchers are taking novel approaches to further improve uptake of the recommended cancer screening and follow-up care, some of which are highlighted below.

Using Electronic Health Records

Electronic health records (EHR) are routinely used in health care settings, including for cancer care (446)Post AR, et al. (2022) JCO Clin Cancer Inform, 6: e2100158. DOI: 10.1200/CCI.21.00158.. Ongoing research is showing the promise of EHR-based interventions in improving adherence to routine cancer screening and follow-up care. As one example, in a nonrandomized controlled trial involving 1,865 patients who were eligible for lung cancer screening, researchers evaluated the effectiveness of integrating electronic health care records into shared decision-making for lung cancer screening (447)Kukhareva PV, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2415383. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15383.. Study was divided into a 12-month baseline period during which no intervention was applied; an 11-month period 1 in which health care professionals were prompted with preventive care reminders, and were provided with a shared decision-making software with integrated EHR and a narrative lung cancer screening guidance in the low-dose computed tomography ordering screen; and a 9-month period 2 in which in addition to the period 1 interventions, patients were sent reminders for lung cancer screening discussion and to receive lung cancer screening (447)Kukhareva PV, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2415383. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15383.. Findings of the study show that the completion of recommended lung cancer screening care services was 16 percent before the intervention and increased to 47 percent at the end of period 2 (447)Kukhareva PV, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2415383. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15383..

Another study used EHR-based interventions to improve timely follow-up after abnormal breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancer screening results (448)Atlas SJ, et al. (2023) JAMA, 330: 1348. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.18755.. The study included nearly 12,000 patients from 44 primary care practices within three health networks who had at least one abnormal cancer screening test result and had not yet followed up. Primary care practices were randomized equally into groups who provided usual care; EHR reminders; EHR reminders and outreach (a patient letter was sent at week 2 and a phone call at week 4); or EHR reminders, outreach, and navigation (a patient letter was sent at week 2 and a navigator outreach phone call at week 4). Findings show that 31.4 percent of patients who received EHR-based reminders, outreach, and navigation completed the recommended follow-up within 120 days of enrolling in the study. In comparison, 22.9 percent of patients completed the recommended follow-up in the usual care group, which did not receive any EHR-based interventions (448)Atlas SJ, et al. (2023) JAMA, 330: 1348. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.18755..

Reducing Structural Barriers

A key reason for suboptimal uptake of cancer screening and follow-up care is structural barriers, such as distance from a screening facility and lack of transportation (29)American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024. Accessed: June 14, 2024.. One way researchers have addressed these barriers is by mailing people kits for collecting samples for cancer screening at home. This approach has been particularly effective for improving adherence to the recommended colorectal cancer screening (450)Huf SW, et al. (2021) J Gen Intern Med, 36: 1958. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-020-06415-8.(451)Mehta SJ, et al. (2024) Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 00: 1. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.04.003.. Furthermore, a recent study showed that when a statewide screening program for patients who are seen at federally qualified health centers is implemented in a way that maximizes the efficiency of the program while maintaining its effectiveness, the mailed to home kits can be cost-effective, with considerable improvement in colorectal cancer screening outcomes over 5 years—preventing 91 to 98 colorectal cancers and averting 46 to 50 colorectal cancer deaths—compared with outcomes when no such program is in place (452)Olmstead T, et al. (2024) Prev Chronic Dis, 21: E30. DOI: 10.5888/pcd21.230266..

Researchers are now applying this strategy to screening for other types of cancer. In a randomized controlled trial of more than 30,000 people, researchers divided individuals who were due or overdue for cervical cancer screening into groups who received usual care (i.e., patient reminders and EHR-based alerts for health care professionals), education (usual care plus educational material about screening), direct mail (usual care plus educational materials and a mailed self-sampling kit), or a choice to opt-in (usual care plus educational materials and the option to request a kit) (454)Winer RL, et al. (2023) JAMA, 330: 1971. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.21471.. Findings show that the overall screening completion rate was the highest in the direct-mail group. Compared to those who received education alone, the screening completion rate was 14.1–16.9 percent higher in the direct-mail group among those who were due or overdue for screening (454)Winer RL, et al. (2023) JAMA, 330: 1971. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.21471..

Accruing evidence suggests that multilevel outreach strategies are also effective in reducing structural barriers and improving screening uptake. In a study of more than one million colorectal cancer screening–eligible individuals, researchers implemented sequential outreach, first with automated mechanisms (such as mailed prescreening notification postcards and FIT kits, automated telephone calls, and postcard reminders), followed by personalized outreach (such as telephone calls, screening offers during office visits, and electronic messaging). Findings of this year-long study show that both automated and personalized outreach strategies substantially increased colorectal cancer screening, achieving absolute increases in screening coverage of 29 percent to 38 percent after the automated outreach and another 11 percent to 15 percent after the personalized outreach (455)Podmore C, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e245295. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.5295..

Implementing Culturally Tailored Strategies Through Community Engagement

Community engagement is an effective strategy in increasing adherence to routine cancer screening and follow-up care, especially among the medically underserved populations. Research indicates that engaging communities in a meaningful way increases awareness about the importance of undergoing routine cancer screening, participating in clinical trials, and reducing exposure to modifiable cancer risk factors (456)Kale S, et al. (2023) Cureus, 15: e43445. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.43445.(457)Wangen M, et al. (2023) Cancer Causes Control, 34: 45. DOI: 10.1007/s10552-023-01690-2.. For example, interventions involving culturally tailored patient navigation significantly increase racial and ethnic minority patient engagement across the cancer care continuum and improve health outcomes (458)Nouvini R, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128: 3860. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.34454.(459)Chan RJ, et al. (2023) CA Cancer J Clin, 73: 565. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21788..

Indigenous populations in the United States, including American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people, have higher incidence of colorectal cancer compared to other populations worldwide (36)Haverkamp D, et al. (2023) Int J Circumpolar Health, 82: 2184749. DOI: 10.1080/22423982.2023.2184749.. As shown in Table 5, the AI/AN populations also have lower uptake of colorectal cancer screening compared to the overall US population. Effective and culturally tailored interventions are urgently needed to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening in these communities.

NCI’s Screen to Save Colorectal Cancer Outreach and Screening Initiative is a national program launched by the NCI Center for Cancer Health Equity. The initiative aims to increase colorectal cancer screening rates among racially and ethnically diverse communities and in rural areas by providing culturally tailored, evidence-based colorectal cancer information, education, and screening resources through community health educators (461)National Cancer Institute. Screen to Save – Colorectal Cancer Screening. Accessed: March 17, 2024.. In a recent study, researchers developed a version of the NCI Screen to Save program that was culturally tailored for the Indigenous and rural populations and, in partnership with the Indigenous and rural community outreach teams and the community advisory board, provided the tailored program to both the Indigenous and rural/ suburban communities (462)Maybee W, et al. (2024) J Cancer Educ, 39: 65. DOI: 10.1007/s13187-023-02376-8..

Participants who received the culturally tailored educational material successfully identified smoking and tobacco use, as well as physical inactivity, as risk factors for colorectal cancer. Furthermore, participants reported that their personal cancer screening experiences have increased their likelihood, as well as the likelihood of their family and friends, to receive routine screening for colorectal cancer. These findings highlight the importance of culturally tailored interventions through community engagement as an effective strategy for increasing screening awareness and adherence among medically underserved populations (462)Maybee W, et al. (2024) J Cancer Educ, 39: 65. DOI: 10.1007/s13187-023-02376-8..

Emerging Technologies for Early Detection of Cancer

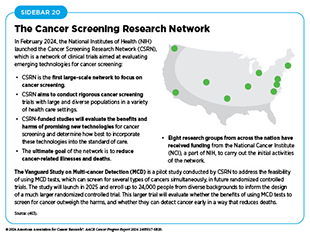

Technological advances in genome sequencing, imaging, detection of cells and molecules in small amounts of samples, and analyses of large amounts of health data are fueling research to develop new and innovative ways to detect cancers early. Recognizing the need to evaluate emerging technologies for cancer screening, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) launched the Cancer Screening Research Network (CSRN) in February 2024 (see Sidebar 20).

Early detection of cancer using artificial intelligence (AI)– powered devices and software and minimally invasive tests are two rapidly evolving research areas with exciting new developments. Both technologies are showing great promise in revolutionizing the cancer care continuum. For example, AI has the potential to accelerate the early detection of cancer, thus saving valuable time for patients and providers before the next course of action can be decided on if cancer is detected. Similarly, minimally invasive tests, such as liquid biopsy tests, are easier for patients, and do not require large-scale infrastructure and thus have the potential to reduce or eliminate the geographic barriers often associated with low uptake of cancer screening. Both technologies are also being tested in other aspects of the cancer care continuum, such as deciding which cancer treatment will be safe and effective for the patient and/or monitoring the patient’s response to the treatment. However, both technologies also carry some drawbacks that must be carefully considered before either can be fully integrated into the standard of care (see Sidebar 21).

Accruing evidence suggests that the use of AI-assisted software and devices in cancer care can substantially reduce the time to make critical health-related decisions. As one example, researchers compared the performance of AI for reading mammograms to the standard method, which involves evaluation of mammograms by two independent health care professionals (464)Lang K, et al. (2023) Lancet Oncol, 24: 936. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00298-X.. Findings show that not only were AI-detected cancers comparable to cancers detected by trained professionals (6.1 versus 5.1 cancers detected per 1,000 screened participants, respectively), but AI-assisted software also reduced the workload, i.e., time spent by trained professionals to evaluate mammograms, by 44.3 percent (464)Lang K, et al. (2023) Lancet Oncol, 24: 936. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00298-X..

Researchers are also exploring the potential of AI in early detection of cancers for which there are no screening guidelines, such as skin cancer and pancreatic cancer. For example, early detection of pancreatic cancer, which is estimated to become the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States by 2040 (356)Rahib L, et al. (2021) JAMA Netw Open, 4: e214708. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4708. and has the lowest 5-year survival rate of 13 percent (4)Siegel RL, et al. (2024) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 12. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21820., poses a significant challenge. Unfortunately, CT scans miss about 40 percent of small pancreatic cancers until they have advanced to a more aggressive stage (465)Kang JD, et al. (2021) Eur Radiol, 31: 2422. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-020-07307-5.. In a recent study, researchers developed an AI model trained on imaging data from more than 3,000 patients with pancreatic cancer for fully automated cancer detection, including small and otherwise difficult-to-detect tumors (466)Korfiatis P, et al. (2023) Gastroenterology, 165: 1533. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.034.. The model helped discriminate visually imperceptible cancerous lesions from normal-appearing pancreases 438 days before the clinical diagnosis, a significant improvement over standard methods (466)Korfiatis P, et al. (2023) Gastroenterology, 165: 1533. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.034.. Other recent studies have shown similar promise of AI-assisted early detection of this devastating cancer type (467)Cao K, et al. (2023) Nat Med, 29: 3033. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-023-02640-w..

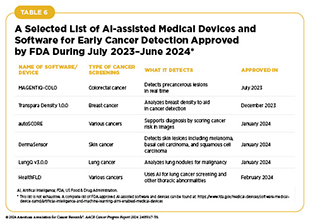

The potential of AI in medicine is also reflected by the FDA approval of numerous AI-assisted software systems for early detection of cancer in recent years (see Table 6). As the applications of AI in cancer science and medicine, including in early detection of cancers, are rapidly evolving, it is important to consider the ethical ramifications of the technology, as well as its potential to exacerbate cancer inequities (see Sidebar 21) (468)Farasati Far B (2023) Explor Target Antitumor Ther, 4: 685. DOI: 10.37349/etat.2023.00160..

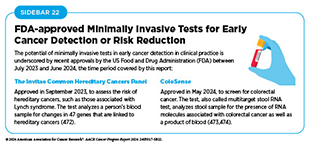

Liquid biopsy procedures are minimally invasive and can detect abnormal cells and/or other materials from tumors, such as small pieces of DNA, RNA, or proteins, that are circulating in the blood. Liquid biopsy–based tests that can detect multiple types of cancer simultaneously are called multicancer detection (MCD) assays or multicancer early detection tests. Liquid biopsy approaches are already in routine use for making treatment decisions and/or monitoring if cancer has returned in patients who have already received cancer treatment (469)Connal S, et al. (2023) J Transl Med, 21: 118. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-023-03960-8.(470)Christodoulou E, et al. (2023) NPJ Precis Oncol, 7: 21. DOI: 10.1038/s41698-023-00357-0.. Because these approaches are minimally invasive, they can be especially beneficial for children and older adults with cancer (471)Fink, J. (2023). Cancer, 129: 1950. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.34882.. During the 12-month period covered by this report (July 2023–June 2024), FDA has also approved two minimally invasive tests for early detection of cancers or determining cancer risks among those who are genetically predisposed (see Sidebar 22).

Liquid biopsy tests are showing promise in detecting cancer types for which there are no population-based screening guidelines. As described above, pancreatic cancer poses a serious challenge to public health because of low survival rates and lack of effective strategies to detect it at early stages of development. It is encouraging that researchers have developed a blood test to accurately detect early-stage pancreatic cancer, according to results from a large study that included nearly 1,000 people from several countries (475)American Association for Cancer Research. An Exosome-based Liquid Biopsy for Non-invasive, Early Detection of Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Multicenter and Prospective Study. Accessed: June 14, 2024.. The test analyzed small pieces of RNA shed by tumors into the bloodstream in combination with a test that detects a protein called CA19-9, which is a marker for pancreatic cancer. The findings show that the combination accurately identified 97 percent of people with early-stage pancreatic cancer (475)American Association for Cancer Research. An Exosome-based Liquid Biopsy for Non-invasive, Early Detection of Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Multicenter and Prospective Study. Accessed: June 14, 2024.(476)Xu C, et al. (2024) Gastroenterology, 166: 178. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.09.050..

Liver cancer has a high mortality rate, with nearly 30,000 deaths estimated to occur in the United States in 2024 alone (4)Siegel RL, et al. (2024) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 12. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21820.. Furthermore, the 5-year survival rate from the disease is only 22 percent, which can increase to more than 70 percent if the cancer is detected early (4)Siegel RL, et al. (2024) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 12. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21820.. However, current tests available to monitor people at high risk of developing liver cancer, such as those with hepatitis B virus infection, do not work well, are not readily available to those who need them, and are expensive. In a new study, researchers used an AI-assisted model to identify small pieces of DNA shed by liver tumors, and then used this knowledge to develop a liquid biopsy test for early detection of liver cancer (477)Foda ZH, et al. (2023) Cancer Discov, 13: 616.. Findings show that the test reliably identified patients with liver cancer, including early-stage disease, in blood samples from hundreds of people (477)Foda ZH, et al. (2023) Cancer Discov, 13: 616..

Although the examples discussed here are encouraging, researchers are calling for large-scale randomized controlled trials to ensure that these tests will improve health outcomes and extend lives for patients, while minimizing cost and unintended adverse effects (478)Carr DJ, et al. (2023) JAMA Intern Med, 183: 1144. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.3603..

Next Section: Inspiring Science. Fueling Progress. Revolutionizing Care. Previous Section: Reducing the Risk of Cancer Development