Pediatric Cancer Trends in the United States

In this section, you will learn:

- The 5-year survival rate for all pediatric cancers combined has increased from 63 percent in the mid-1970s to 87 percent in 2015–2021.

- Between 2000 and 2020, mortality rates for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) declined by an average of 3.3 percent per year, thanks to improved risk stratification and availability of new FDA approved targeted therapies and immunotherapies. However, comparable progress has not been observed across all pediatric cancers.

- A majority (60% to more than 90%) of pediatric cancer survivors develop one or more chronic, treatment-related health conditions affecting multiple organ systems, including cardiac, pulmonary, endocrine, reproductive, and neurocognitive disorders, as well as second cancers and impaired growth and development.

- Pediatric cancers are rare, biologically distinct, and unevenly studied when compared to adult cancers. Survival gains are concentrated in the more common pediatric cancers, while rare or more aggressive tumors—characterized by metastases at diagnosis or poor response to therapy—continue to have dismal outcomes.

- Pediatric cancer incidence and survival vary by race, ethnicity, geography, and social drivers of health; underserved populations experience higher mortality and more barriers to care.

- Progress against pediatric cancers depends on robust public funding, committed advocacy on behalf of pediatric patients, continued national and international collaborations, private–public partnerships, philanthropic investment, and policy incentives to close gaps in funding, research infrastructure, and access to innovative therapies to accelerate pediatric drug discovery and development.

Research is the foundation of progress against the diverse diseases that make up pediatric cancers. Research drives improvements in survival and quality of life for children (ages 0 to 14) and adolescents (ages 15 to 19) worldwide by fueling clinical breakthroughs and informing public policies that promote health. Decades of discoveries across basic, clinical, translational, and population sciences have enhanced our understanding of pediatric cancers, which in turn has laid the groundwork for advances in early detection, diagnosis, treatment, and long-term survivorship.

Saving Lives Through Research

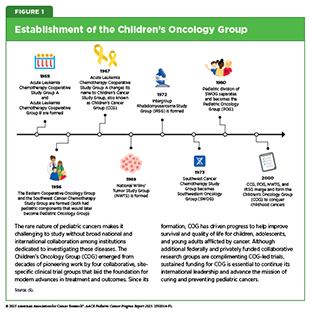

Early progress in pediatric cancers dates to the mid-20th century, when several drugs were introduced for the treatment of children with leukemia (1-3). Use of these drugs improved median survival from 8 months for patients diagnosed between 1948 and 1952 to 22 months for those diagnosed in the mid-1950s (4)Burchenal JH, et al. (1953) Blood, 8: 965.. These treatment advances spurred the creation of the first collaborative group dedicated to pediatric cancer care—the Acute Leukemia Chemotherapy Cooperative Study Group A—which brought together scientists from major research institutions across the United States (US) to investigate pediatric leukemia.

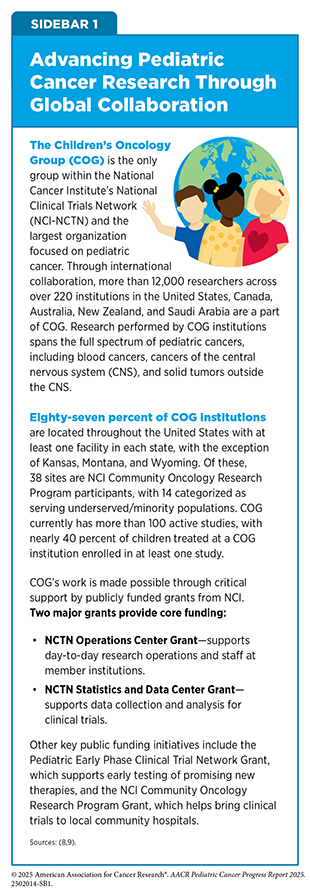

Collaborative efforts (i.e., multicenter and multidisciplinary clinical trials to overcome the challenge of smaller patient populations) have emerged as the cornerstone of progress against pediatric cancers (see Sidebar 1). Clinical research led by pediatric cancer–focused cooperative groups has driven major breakthroughs in pediatric oncology. These advances include improved methods for staging tumors, assessing tumor size and spread, optimizing treatment approaches, and understanding the long-term effects of childhood cancer therapies (6)O’Leary M, et al. (2008) Semin Oncol, 35: 484.. As a result, the overall 5-year survival rates for pediatric cancers have risen from 63 percent in the mid-1970s to 87 percent between 2015 and 2021 (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR

Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.(7)Erdmann F, et al. (2021) Cancer Epidemiol, 71: 101733..

Advances in pediatric cancer highlight the necessity of the ongoing, multidisciplinary collaborations that span both research and patient care as well as the robust, predictable, and sustained public funding, as exemplified by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) and the support of its research activities by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (see Figure 1) (6)O’Leary M, et al. (2008) Semin Oncol, 35: 484.. In the United States (US), 9 out of 10 children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer are treated at a COG member institution, where they receive the most promising therapies available (8)Withycombe JS, et al. (2019) J Pediatr Oncol Nurs, 36: 24..

Research-driven advances across the clinical cancer care continuum have led to a considerable decrease in pediatric cancer mortality. Over the past 50 years, overall cancer death rates among US children and adolescents have declined by 70 percent (6.3 per 100,000 to 1.9 per 100,000) and 63 percent (7.2 per 100,000 to 2.7 per 100,000), respectively. These improvements reflect the identification and therapeutic targeting of cellular and molecular drivers of cancer, complemented by a greater understanding of biology and advances in precision medicine including immunotherapy, surgical techniques, refinements in radiotherapy and chemotherapy dosing, and improvements in supportive care (see Figure 2). Despite these tremendous gains, survival rates have only increased, on average, by only about 0.5 percent annually since 2000 (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR

Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.. The minimal improvements observed in more recent years underscore the urgent need to accelerate progress in pediatric drug discovery and development.

Advances in identifying prognostic markers and clinical care over the past several decades have led to marked improvements across specific pediatric cancer types. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common cancer among children and adolescents, has seen substantial improvements in survival. Between 2000 and 2020, mortality rates among children and adolescents declined by an average of 3.3 percent per year, reflecting the impact of advances in risk stratification, targeted therapy, and other treatment innovations (11)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER

Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.. Risk stratification allows patients with specific genetic features to receive tailored treatment plans and disease monitoring. Minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring—which detects a very small number of cancer cells in the body and is now a standard practice—guides treatment intensity by identifying patients at higher risk of relapse and can detect disease weeks to months earlier than conventional imaging or blood tests, contributing significantly to improved survival (12)Kruse A, et al. (2020) Int J Mol Sci, 21..

Genetic characteristics also influence ALL prognosis and outcomes with some. Specifically, high hyperdiploidy and ETV6::RUNX1 rearrangements are associated with favorable prognosis, whereas a range of alterations such as hypodiploidy (fewer than 44 chromosomes), MLL rearrangements, or BCR::ABL1 is linked to high-risk clinical features or poor outcomes (see Somatic Mutations, and Molecular Insights Driving Risk Stratification and Treatment) (13)Hunger SP, et al. (2015) N Engl J Med, 373: 1541..

Advances in molecularly targeted therapy and immunotherapy have improved outcomes for nearly all ALL subtypes (see Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment). For example, 3-year survival has nearly doubled for individuals with Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL treated with the molecularly targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib (Gleevec). Precision medicine has improved outcomes in high-risk neuroblastoma, with anti-GD2 antibodies (e.g., dinutuximab and naxitamab) approved over the past decade (14)DuBois SG, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31831.. Newly FDA-approved targeted treatments and immunotherapies continue to enhance survival and reduce mortality across a range of pediatric cancers. The cumulative impact of these advances is reflected in significant declines in all-cause mortality among pediatric cancer survivors diagnosed between the 1970s and 1990s, dropping from 10.7 percent to 5.8 percent (15)Armstrong GT, et al. (2016) N Engl J Med, 374: 833., indicating improved long-term health and quality of life. Subsequently, more than 521,000 pediatric cancer survivors were living in the United States in 2022, with the majority living at least 5 years or more after diagnosis (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.. Despite these gains, important challenges remain in understanding and addressing the unique burden of pediatric cancers in the United States.

Ongoing Challenges in Pediatric Cancers

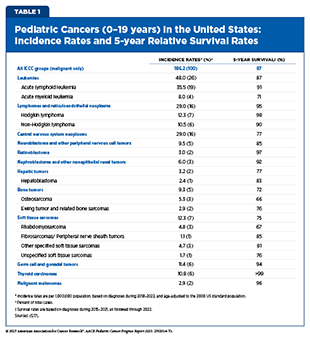

In 2025, an estimated 14,690 children and adolescents will be diagnosed with cancer, compared to roughly two million cases in adults (16)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.. Overall, the most common cancers in children and adolescents (ages 0 to 19) are leukemias, CNS tumors, and lymphomas (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1) (16)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.. When examining cancers by age group, the five most common cancers among children ages 0 to 14 are leukemia, CNS tumors, lymphomas, neuroblastoma and related tumors, nephroblastoma and other nonepithelial kidney tumors. For adolescents ages 15 to 19, the five most common cancers are lymphomas, leukemias, thyroid cancer, germ cell and gonadal tumors, and CNS tumors.

Over several decades, sustained progress in cancer research and treatment—driven by advances in identifying and therapeutically targeting cellular and molecular drivers of cancer—has contributed to steady improvements in outcomes for children and adolescents (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers, and Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment).

In the United States, 5-year relative survival rates for pediatric cancers have increased substantially over the past five decades. However, progress has slowed in recent years, with survival improving by only 0.5 percent per year since 2000 (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.. Survival outcomes also vary considerably by cancer type and age group (see Supplementary Table 1). As one example, adolescents and young adults (AYAs) experience notably lower 5-year survival rates compared with children diagnosed with the same cancers. Specifically, survival for AYAs with ALL is 63.2 percent compared with 91.6 percent in children; for Ewing sarcoma of the bone, 55.3 percent versus 76.9 percent; and for Ewing sarcoma of the soft tissue, 60.8 percent versus 84.7 percent (18)Keegan THM, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 630.. While survival disparities remain, attention has increasingly turned to the lasting health effects faced by those who survive pediatric cancer.

Pediatric cancers constitute a major public health challenge, as they are the leading cause of disease-related mortality in children and a substantial contributor to long-term morbidity in survivors. While survival has improved, many pediatric cancer survivors live with chronic and often serious health conditions related to their cancer or its therapy (see Challenges Faced by Pediatric Cancer Survivors). Studies show that 60 percent to more than 90 percent of pediatric cancer survivors develop one or more chronic health conditions following their cancer diagnosis (19)Phillips SM, et al. (2015) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 24: 653.(20)Bhakta N, et al. (2017) Lancet, 390: 2569.. These treatment-related adverse effects can involve multiple organ systems and include heart and lung problems, second cancers, impaired growth and development, endocrine and reproductive disorders, and neurocognitive impairments (21)Bhatia S, et al. (2023) Jama, 330: 1175..

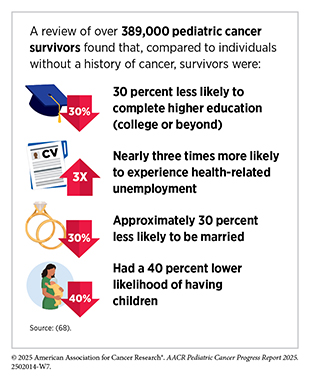

However, as pediatric cancer survivors continue to live longer, mortality related to late recurrence, second primary cancers and other treatment-related toxicities (i.e., cardiac events or pulmonary conditions) has declined, while there was a simultaneous increase in mortality from external causes, including accidents and suicide (22)Yeh JM, et al. (2020) JAMA Oncol, 6: 350.. Survivors and their families often face psychosocial challenges, difficulties with social relationships and educational attainment, as well as financial hardships related to the costs of medical care (22)Yeh JM, et al. (2020) JAMA Oncol, 6: 350.. Continued research to address the complex survivorship needs of the growing number of pediatric cancer survivors must remain a public health priority (see Supporting Survivors of Pediatric Cancers).

Challenges of Rare Disease Research

NCI defines rare cancer as a cancer that occurs in fewer than 15 out of 100,000 people each year in the United States, placing all pediatric cancers within this category. The Joint Action on Rare Cancers, in cooperation with the European Cooperative Study Group for Pediatric Rare Tumors, classifies very rare cancers as tumors that occur in less than 2 children per 1 million annually (23)Ferrari A, et al. (2019) Eur J Cancer, 110: 120.. Within this already rare group, some cancer types occur even less frequently, making them especially difficult to study.

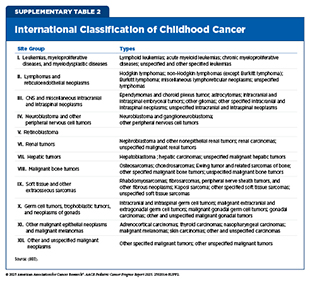

Due to unique biological and histologic characteristics, pediatric cancers are classified primarily by tumor morphology—the appearance of cells and their organization—rather than by anatomic site, which is the convention for adult cancers (24)National Cancer Institute. International Classification of Childhood Cancer (ICCC) – SEER Documentation. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. This approach reflects the fact that many pediatric cancers arise from undifferentiated cells with distinct histologic features and can develop in multiple sites throughout the body, such as neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma (see Molecular and Cellular Influences Driving Pediatric Cancers) (25)Chen X, et al. (2024) Nat Rev Cancer, 24: 382.. Because of these biological and histologic differences from adult tumors, specialized classification of pediatric cancers is required for diagnosis.

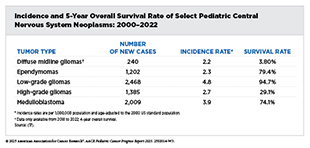

To standardize reporting, the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (ICCC) groups pediatric cancers into 12 categories (see Supplementary Table 2). Although this classification has enabled easier interpretation and dissemination of incidence and mortality data, ICCC’s aggregation of diverse cancer types can obscure the true burden of cancers with lower incidence but disproportionately high mortality. This, in turn, may hinder efforts to identify priorities for research, determine allocation of resources, and improve outcomes for the children most at risk. Pediatric CNS tumors illustrate this limitation, as the overall 5-year survival rate for this group is 77 percent, yet certain subtypes have extremely poor prognoses. For instance, children diagnosed with diffuse midline gliomas have a survival rate of only 4 percent (17)Surveillance Research Program. National Cancer Institute SEER Stat software. version 9.0.41.4..

Major challenges in pediatric cancer research, specifically rare tumor research, include the small number of patients available to participate in clinical trials and observational studies; clinical heterogeneity—differences in patient characteristics, disease severity and outcomes, and treatments used; limited understanding of the biology of rare tumors; lack of preclinical models; lack of new therapies; less interest from pharmaceutical companies; and constrained funding and limited infrastructure (26)Schultz KAP, et al. (2023) EJC Paediatr Oncol, 2.. The consequences of these challenges are evident by the heterogeneity of outcomes. For example, the overall 5-year survival rates are only 60.7 percent for adrenocortical carcinoma—a rare cancer of the adrenal glands—22.6 percent for desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSCRT)—an aggressive soft tissue sarcoma—and just 2.2 percent for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), an aggressive form of brain cancer (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.(27)Wu D, et al. (2025) Pediatr Surg Int, 41: 84.(28)Hoffman LM, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 1963.. In contrast, the overall 5-year survival rates for children and adolescents diagnosed with leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma are 87 percent and nearly 100 percent, respectively (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.(29)Carceller F (2019) Transl Cancer Res, 8: 343..

In the United States, COG engages its Rare Tumor Committee to study cancers that are ultra-rare or understudied in children and adolescents (30). These include tumors classified within group XI of ICCC—other malignant epithelial neoplasms and melanomas—such as adrenocortical, nasopharyngeal, colorectal, and thyroid cancers; melanoma; pleuropulmonary blastoma; retinoblastoma; gonadal stromal, pancreatoblastoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors; non-melanoma skin cancers; neuroendocrine tumors; and desmoplastic small round cell tumors (26)Schultz KAP, et al. (2023) EJC Paediatr Oncol, 2.(30)Pappo AS, et al. (2010) J Clin Oncol, 28: 5011.. Collectively, these tumors account for less than 10 percent of all pediatric cancers (30)Pappo AS, et al. (2010) J Clin Oncol, 28: 5011..

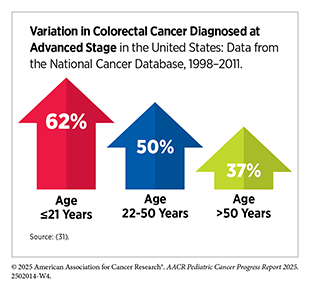

Within the pediatric population, some cancers (i.e., thyroid and CRC) are more common in adolescents than children. As one example, although only about 5 in 1 million children in the United States are diagnosed with CRC annually (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.(11)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.(16)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10., they are often diagnosed at an advanced stage with poor outcomes (31)Poles GC, et al. (2016) J Pediatr Surg, 51: 1061.. Despite presenting with disease that resembles early-onset CRC in adults, children are 22 percent more likely to die from the disease than adults diagnosed between ages 22 and 50 (31)Poles GC, et al. (2016) J Pediatr Surg, 51: 1061.. The difference observed in outcomes for individuals younger than 21 diagnosed with colorectal cancer has been attributed to the biology of the tumor rather than disparate treatment modalities (31)Poles GC, et al. (2016) J Pediatr Surg, 51: 1061.. This example underscores the need for pediatric-specific molecular profiling, development of tailored therapies, and more robust outcome data collection for meaningful improvements in survival for children with CRC.

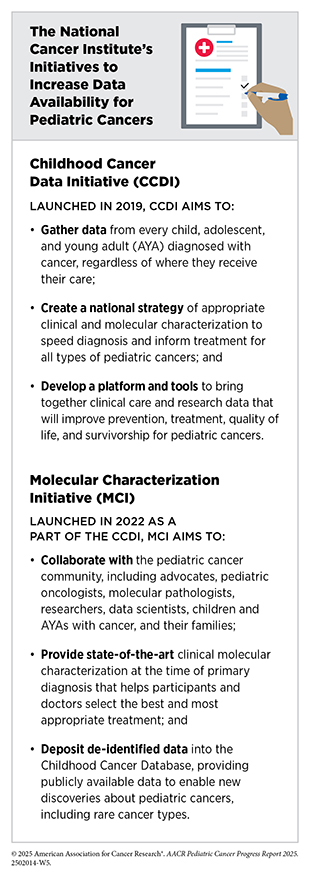

To overcome the lack of data needed to accelerate progress against rare pediatric cancers, such as detailed information on tumor biology, COG collects patient samples (e.g., blood, tumor tissues, and urine) to advance the development of targeted therapies. Through its biospecimen collection initiative, Project:EveryChild, partially supported by NCI, COG gathers samples from patients with all types of pediatric cancer. In 2022, NCI further expanded efforts with the Molecular Characterization Initiative—part of the NCI’s Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (see Shared Data and Collaborations Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research)—to provide comprehensive clinical sequencing of pediatric tumors, including rare types. Together, these strategies are increasing the representation of rare childhood cancers in the NCI-sponsored COG biobank and allowing for precision diagnosis, treatment, and determining clinical trial eligibility (26)Schultz KAP, et al. (2023) EJC Paediatr Oncol, 2.(32)Flores-Toro J, et al. (2025) J Natl Cancer Inst.. To address the needs of patients with very rare cancers, CCDI is also launching the Coordinated Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult Rare Cancer Initiative, which provides comprehensive molecular profiling through the MCI in addition to collection and extraction of clinical data (32)Flores-Toro J, et al. (2025) J Natl Cancer Inst.(33)Jagu S, et al. (2024) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 71: e30745..

NCI-funded initiatives underscore the need for sustained funding in pediatric cancer research, particularly to improve outcomes for children and adolescents affected by rare cancers (see Policies Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research and Care). Equally important, meaningful progress will require cross-disciplinary international collaborations to assemble sufficiently large patient cohorts for impactful research. NCI, in partnership with Cancer Research UK, founded Cancer Grand Challenges (CGC), a global research initiative to overcome the most difficult challenges in cancer research, which includes developing targeted therapies in pediatric oncology (34)Foulkes I, et al. (2021) Cancer Discov, 11: 23.. Currently, CGC sponsors three collaborative teams (NexTGen, KOODAC, and PROTECT) to tackle challenges centered on developing therapeutics for children and adolescents with cancer (see Shared Data and Collaborations Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research).

Uneven Progress Against Pediatric Cancers

In the United States, 1,050 children and 600 adolescents are estimated to die from cancer in 2025 (16)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.. However, the impact of the pediatric cancer burden extends far beyond mortality, encompassing the significant years of life lost, long-term health complications among survivors, profound emotional and financial strain on families, and broader societal costs.

Over the past several decades, major advances in cancer prevention, early detection, and treatment have contributed to substantial improvements in survival for many adult cancers (35)Goddard KAB, et al. (2025) JAMA Oncol, 11: 162.. However, pediatric cancers have not seen comparable progress. As one example, lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer deaths in adults, has benefited enormously from advances in precision medicine over the past 15 years. More than 45 new therapies, including molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapies, have been approved by FDA for patients with advanced lung cancer. Thanks to these advances, lung cancer mortality rates have declined by 38 percent since 2010 (11)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.. In sharp contrast, pediatric CNS tumors, which are the leading cause of cancer-related death in children, have seen only four new FDA-approved treatments over the same time frame. Alarmingly, mortality from pediatric CNS tumors has increased by nearly 8 percent since 2010, reflecting the lack of meaningful progress despite ongoing research (11)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.. Advances in precision medicine have also transformed outcomes in other previously intractable cancers in adults, such as metastatic melanoma, yet similar breakthroughs have not been realized for aggressive pediatric cancers such as rhabdomyosarcoma.

Although 40 percent of adult cancers are attributable to modifiable risk factors, the relationship between pediatric cancers and modifiable exposures remains poorly understood. Moreover, although tumor sequencing has advanced the understanding of inherited genetic alterations driving pediatric tumors, only 10 to 18 percent of cases can be explained by genetic predisposition syndromes (see Pediatric Cancer Predisposition and Surveillance) (36)Brodeur GM, et al. (2025) Clin Cancer Res, 31: 2581.(37)Roganovic J (2024) World J Clin Pediatr, 13: 95010.. In many cases, this lack of information is due to our limited understanding of the normal development of the tissues and organs in which pediatric cancers arise, as well as the lack of suitable experimental models that reflect the inherited genetic drivers of these cancers. Without strong investment in research on cancer predisposition genes and the causes of pediatric cancers, opportunities for prevention and early detection will be missed, survival gains will plateau, and the gap with adult outcomes will widen.

While significant progress has been made against pediatric ALL, individuals diagnosed with less common cancers, such as high-grade gliomas (i.e., DIPG and glioblastoma multiforme) and certain sarcomas, continue to face dismal prognoses, with the overall survival often around 20 percent or less (38)Gallitto M, et al. (2019) Adv Radiat Oncol, 4: 520.. Specifically, children with DIPG only survive about 12 months after diagnosis (39)Kim HJ, et al. (2023) Cancer Res Treat, 55: 41.. The poor prognosis is largely attributed to the lack of progress in advancing treatments for this disease despite a strong understanding of the biological underpinnings of DIPG (see Personalizing the Treatment of Brain Tumors).

The majority of new cancer drugs are first developed for, tested, and approved in adult populations, even when they are evaluated in cancers relevant to pediatric patients (40)Arfè A, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 917., leaving pediatric applications years behind. Specifically, after a new cancer drug receives FDA approval for adults, it can take as long as 10 years before it becomes available for pediatric use (41)Cleveland C, et al. (2025) Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 9: 544.. Notably, research has shown that there is a very small overlap in the genomic alterations in adult cancers when compared to pediatric cancers. Pediatric cancers that share molecular features with adult malignancies (e.g., melanoma) are often treated with adult regimens that are not tailored to pediatric patient’s developmental stage, raising concerns about efficacy, toxicity, and long-term adverse effects (31)Poles GC, et al. (2016) J Pediatr Surg, 51: 1061.(42)Sondak VK, et al. (2024) Curr Oncol Rep, 26: 818..

Limited funding remains a significant barrier to developing new and effective treatments for pediatric cancers (see Investing in Pediatric Cancer Research to Secure a Healthier Future). Currently, the majority of funding for therapy development to treat pediatric cancers is provided by NCI and philanthropic organizations, while pharmaceutical companies have little incentive to invest, given the small patient population.

Restricted access to experimental therapies, regulatory and drug approval complexities, and the difficulty of conducting early-phase international trials for rare tumors further hinder progress. In this context, international collaborations are critical to accelerate progress against pediatric cancers. For example, COG uses its international research network in Canada, Europe, and Australia to enroll more patients in clinical trials, ensuring that children and adolescents with very rare cancers can also access promising new investigational therapies. Other international pediatric trial consortia, such as the COllaborative Network for NEuro-oncology Clinical Trials (CONNECT), play a critical role in expanding access to clinical trials and advancing new therapies (see Global State of Pediatric Cancer Clinical Trials). Pooling patients and resources across institutions around the globe, makes it possible to accelerate discoveries and improve outcomes for children and adolescents worldwide.

Pediatric Cancer Disparities

Disparities in incidence and outcomes remain a critical challenge, attributable to a lack of equitable access to treatment for children and adolescents with cancer and affecting their quality of life after therapy. NCI defines cancer disparities as adverse differences in cancer-related measures, such as number of new cases, number of deaths, cancer-related health complications, survivorship and quality of life after cancer treatment, screening rates, and cancer stage at diagnosis, that exist among certain population groups. Children and adolescents with cancer face these inequities, underscoring the need to better understand and address the social, biological, and systemic factors that drive cancer disparities.

In general, cancers are more frequently diagnosed in boys, who also have a slightly lower 5-year survival rate than girls (86.4 percent vs. 87.7 percent, respectively) (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.(11)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.. Beyond these sex-based differences, disparities in cancer incidence and outcomes are more pronounced across US racial and ethnic minority groups and other medically underserved populations, both overall and for specific cancer types. For example, while overall pediatric cancer incidence was historically the highest among non-Hispanic White (NHW) individuals, this shifted in 2012 with American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) individuals having the highest incidence rates (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.. Since then, incidence rates have alternated between these two groups, with the most recent data from 2022 indicating that Hispanic individuals have the highest rate (200.1 [Hispanic] vs. 185.1 [AI/AN] vs. 136.5 [NHW] per 1 million) (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.(11)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025..

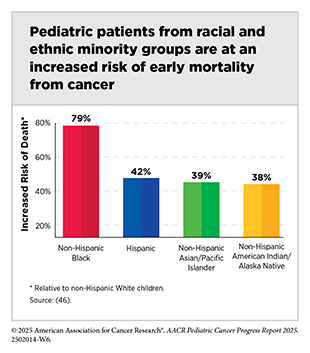

Considerable disparities in mortality are also observed in pediatric cancers. A national study of over 132,000 children diagnosed with leukemia, lymphoma, CNS tumors, and non-CNS solid tumors between 2004 and 2020 found that non-Hispanic Black (NHB) individuals were 28 percent more likely to die from their cancer than children and adolescents of any other race (43)Chidiac C, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31742.. Five-year relative survival is generally higher among NHW and Asian/Pacific Islander AYAs than among NHB, Hispanic, and AI/AN AYAs (18)Keegan THM, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 630.. A smaller study of more than 2,000 children with ALL found that those with higher proportions of Native American or African genetic ancestry had poorer outcomes compared to children with majority European, Asian, or Southeast Asian ancestry (44)Lee SHR, et al. (2022) JAMA Oncol, 8: 354.. Differences in outcomes within subgroups of certain racial minorities have also been reported. Specifically, among US children diagnosed with ALL, the risk of death was 42 percent higher in East Asian patients and 50 percent higher in Southeast Asian patients compared to NHW patients (45)Hashibe M, et al. (2025) Int J Cancer, 156: 1563..

Disparities in pediatric cancer outcomes are not limited to race and ethnicity; they also extend to geography and other social drivers of health (SDOH)—including household income, parental education, access to quality health care, housing stability, food security, and neighborhood environment (see Figure 3). Children and adolescents residing in rural areas without close access to urban medical centers are nearly 20 percent more likely to die from their cancer than those living in urban areas (47)Hymel E, et al. (2025) Cancer Epidemiol, 94: 102705.. Furthermore, the excess risk of death can vary considerably based on cancer type. Children and adolescents with neuroblastoma, retinoblastoma, and renal tumors who reside in rural areas face at least a 35 percent higher risk of mortality compared to those living in urban areas (47)Hymel E, et al. (2025) Cancer Epidemiol, 94: 102705..

In addition to biological and clinical factors, SDOH can also shape outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer (48)Asare M, et al. (2017) Oncol Nurs Forum, 44: 20.(49)Warnecke RB, et al. (2008) Am J Public Health, 98: 1608.. Children are not in direct control of these circumstances, but they are deeply affected by the conditions experienced by their parents or guardians. Limited access to reliable transportation, time off from work, or childcare for unaffected siblings may prevent families from reaching specialized cancer centers for timely diagnosis and/or treatment (46)Preuss K, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31520.. Similarly, financial strains can affect a family’s ability to afford extensive hospitalization, obtain supportive care, participate in clinical trials, or manage the long-term health needs that often accompany pediatric cancer.

Although research on the impact of SDOH on pediatric cancer burden is still emerging, the current evidence is compelling. One study found that pediatric patients from households with a median income below $63,000, those covered by public insurance or those with no insurance, and those living more than 60 miles from a treatment facility had an increased risk of death of 11 percent, 16 percent, 36 percent, and 20 percent, respectively (43)Chidiac C, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31742.. Pediatric patients living in disadvantaged neighborhoods also experience worse outcomes (50)Karvonen KA, et al. (2025) Cancer, 131: e35677.(51)Winestone LE, et al. (2025) Cancer, 131: e35863.(52)Ohlsen TJD, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 141.(53)Umaretiya PJ, et al. (2025) JAMA Netw Open, 8: e2458531.. A recent study developed an area-level socioeconomic composite score—based on median household income and the percentage of residents without a high school degree—to capture neighborhood disadvantage and its relation to outcomes in children with Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, and hepatoblastoma. Pediatric patients who resided in areas with higher neighborhood disadvantage scores were significantly more likely to die from these cancers (54)Nofi CP, et al. (2025) J Pediatr Surg, 60: 162216..

NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers (CCC) and COG-affiliated sites meet rigorous standards for transdisciplinary, state-of-the-art research aimed at advancing cancer prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of pediatric cancers. Children and adolescents treated at these sites often experience better outcomes than those treated elsewhere (55)Wolfson J, et al. (2014) J Natl Cancer Inst, 106: dju166.(56)Wolfson J, et al. (2017) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 26: 312.(57)Wolfson J, et al. (2014) Blood, 124: 556.(58)Wolfson JA, et al. (2023) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 21: 881.. For instance, pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who were treated at non–CCC-COG sites were nearly twice as likely to die as pediatric patients treated at CCC-COG sites (56)Wolfson J, et al. (2017) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 26: 312.. These disparities likely reflect the comprehensive care model of CCC-COG institutions—which includes enhanced supportive and psychosocial services—combined with greater access to clinical trials and the expertise of clinicians engaged in cutting-edge research (58)Wolfson JA, et al. (2023) J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 21: 881..

Collectively, this evidence underscores how non-biological factors such as income, education, area of residence, and access to care play a critical role in shaping outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer. These social drivers may also influence biological processes. As an example, chronic stress associated with economic hardship can alter immune function and physiological responses to therapy, potentially contributing to poorer outcomes even among pediatric patients receiving equivalent inpatient treatment.

While some disparities in the incidence and mortality of pediatric cancers among racial and ethnic minority groups are because of SDOH, not all differences are explained by these factors, suggesting genetic or biological mechanisms may also contribute to differences in survival. This is exemplified by findings from a recent review demonstrating that individuals with high-risk neuroblastoma treated at COG institutions and enrolled in clinical trials still faced disparities in outcomes, despite access to high-quality care and novel therapies (53)Umaretiya PJ, et al. (2025) JAMA Netw Open, 8: e2458531..

Continued investment in research is, therefore, critical to uncover these mechanisms, advance our understanding of pediatric cancer disparities, and develop therapies that can improve outcomes for all children and adolescents.

Funding Pediatric Cancer Research: A Vital Investment

Significant progress in pediatric cancer survival has been driven by decades of collaborative research that has transformed the standard of care for many pediatric cancers in addition to improvements in survivorship care (see Supporting Survivors of Pediatric Cancers). In particular, clinical advances made during the late 20th century greatly improved outcomes for many of the most commonly diagnosed pediatric cancers (6)O’Leary M, et al. (2008) Semin Oncol, 35: 484.. These breakthroughs have been made possible through sustained investment from the federal government as well as critical support from philanthropic initiatives (see Investing in Pediatric Cancer Research to Secure a Healthier Future). Continued robust, predictable, and sustained funding is essential to maintain the pace of progress, especially for rare and aggressive cancers, to develop new model systems including patient-derived models that can accelerate discoveries in pediatric cancer biology, to ensure every child and adolescent has equal access to cutting-edge treatments, and to address long-term physical and mental health effects experienced by pediatric cancer survivors. Ultimately, more effective and less toxic therapy will be needed to cure the currently uncurable, and to reduce the short- and long-term toxicities that affect many survivors.

Economic Toll of Pediatric Cancers

Although survival outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer have improved markedly, the economic toll of these diseases remains profound (see Challenges Faced by Pediatric Cancer Survivors). In the context of adult cancer, financial toxicity—defined as the financial problems a patient experiences related to the cost of medical care—is typically centered on the individual patient. In pediatric cancers, however, the financial and social impact reverberates across the entire family unit and society.

Parents often experience lost wages or jobs due to the need for extended caregiving, while simultaneously shouldering new expenses, such as travel to specialized cancer centers, temporary housing near treatment facilities, and childcare for siblings (see Supporting Parents and Other Caregivers) (59)Bona K, et al. (2014) J Pain Symptom Manage, 47: 594.(60)Bona K, et al. (2016) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 63: 105.. Out-of-pocket costs for medications, rehabilitation, and long-term follow-up visits further compound the financial strain, persisting well beyond the active treatment phase, particularly for survivors managing late effects (59)Bona K, et al. (2014) J Pain Symptom Manage, 47: 594.(60)Bona K, et al. (2016) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 63: 105.(61)Dussel V, et al. (2011) J Clin Oncol, 29: 1007.. An estimate from 2017, combining both hospital costs and parental loss of wages, placed the total economic cost of childhood cancer in the United States at approximately $833,000 per patient (62)Environmental Protection Agency. NIEHS/EPA Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Centers Impact Report: Protecting Children’s Health Where They Live, Learn, and Play. Accessed: August 31, 2025..

At the population level, the societal burden of pediatric cancers is substantial. Because childhood cancers occur early in life, each premature death represents decades of potential life, and societal contributions lost. One way to measure this is through disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), a measure of health outcomes that combines years of life lost due to premature mortality with years lived with disability or impaired health (63)Parsons SK, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 3260.(64)Murray CJ (1994) Bull World Health Organ, 72: 429.. For survivors, long-term health complications—such as chronic physical and mental conditions or late effects of treatment that can reduce educational attainment, limit workforce participation, and necessitate ongoing medical care—collectively diminish productivity and quality of life (21)Bhatia S, et al. (2023) Jama, 330: 1175.. In the United States, the estimated DALYs associated with pediatric cancers were over 158,000 in 2021, which is equivalent to 158,000 years of healthy life lost due to premature death and long-term disability in a single year (65)Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare. Accessed: August 31, 2025..

Globally, between 2020 and 2050, pediatric cancer treatment is projected to cost over $594 billion. However, interventions that reduce the burden of these cancers could save over 318 million life years and generate nearly $2.6 trillion in productivity gains, more than four times the cost of treatment (66)Atun R, et al. (2020) Lancet Oncol, 21: e185.. This equates to a return of $3 for every $1 invested in pediatric cancer research (66)Atun R, et al. (2020) Lancet Oncol, 21: e185.(67)NIH’s Role in Sustraining the US Economy 2025 Update. Accessed: July 1, 2025..

Taken together, the dual burden on families and society, both in the United States and globally, underscores the importance of continued investment in pediatric cancer research, treatment innovation, and survivorship care. Sustained and equitable funding is essential not only to alleviate the economic consequences borne by families but also to reduce the broader societal impact of pediatric cancers across the life course.

Framework for Funding Pediatric Cancer Research

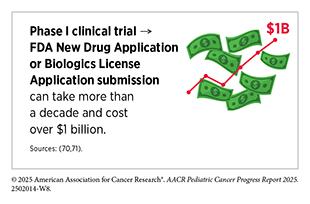

In the United States, breakthroughs in pediatric cancer care have been driven largely by sustained funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (see Investing in Pediatric Cancer Research to Secure a Healthier Future). In 2024, $729 million was allocated across 1,280 pediatric cancer research projects (69)National Institutes of Health RePort. Funding for Various Research, Condition, and Disease Categories. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Yet, the cost of bringing a single cancer drug to market can exceed $1.2 billion, with the majority of expenses concentrated in preclinical and clinical development (70)Sertkaya A, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2415445.. This stark imbalance between the resources required for drug development and the federal funds dedicated to pediatric cancer research underscores the urgent need to reimagine the current funding framework and identify innovative approaches to accelerate the discovery and delivery of effective therapies for children and adolescents with cancer.

The pharmaceutical industry plays a significant role in the development of drugs to treat adults with cancer. Of over 26,000 clinical trials conducted in adult cancer drug discovery from 2008 to 2022, nearly 32 percent were industry-sponsored compared to just under 7 percent funded by the federal government (72)Unger JM, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 3917.. However, in pediatric drug development, the pharmaceutical industry has had limited involvement because of financial disincentives (73)Das S, et al. (2018) JAMA Oncol, 4: 1274.(74)Addressing the Barriers to Pediatric Drug Development: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC)2008.. As an example, refractory pediatric cancers, cancers that don’t respond to treatment, often require combination therapies. Conducting these studies is particularly challenging, as it requires coordination and data-sharing among multiple drug companies, which can be difficult to negotiate and implement.

Further compounding these challenges, pediatric cancers encompass a distinct spectrum of diseases, many of which are genetically and biologically different from adult cancers and may not benefit from therapies developed for adult indications. Unlike drug development for adults, drug development for children must account for the rapid biological and developmental changes that occur throughout childhood and adolescence (see Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment) (74)Addressing the Barriers to Pediatric Drug Development: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC)2008.. Children and adolescents have unique physiology, organ function, immune system, and metabolism, all of which change substantially from infancy to adolescence to adulthood, influencing how drugs are absorbed, distributed, and metabolized in the body (75)Kearns GL, et al. (2003) N Engl J Med, 349: 1157.(76)McKinney RE, Jr. (2003) Pediatrics, 112: 669.. The rarity of these cancers further complicates trial design, requiring multicenter or international collaborations to recruit adequate numbers of patients.

To bridge the funding gap, a reimagined framework for pediatric cancer research is needed and will require leveraging multiple strategies. One such initiative, the Pediatric Advanced Medicines Biotech, would help increase the number of cell and gene therapies for pediatric cancers by partnering with the academic ecosystem, manufacturing products in academic facilities, and working closely with regulatory bodies to ensure new therapies reach the children and adolescents who need them most (77)Mackall CL, et al. (2024) Nat Med, 30: 1836..

Partnerships between public and private funding sources can help distribute the costs of drug development while accelerating the translation of promising discoveries into clinical trials. Policy and regulatory incentives, such as extended market exclusivity, tax credits, or streamlined approval pathways for pediatric indications, can encourage greater investment from industry (see Policies Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research and Care). Philanthropic organizations, which have helped filled critical gaps in pediatric cancer funding, remain essential for supporting high-risk, high-reward projects that might otherwise be overlooked (see Sidebar 2).

Incorporating health economic evaluations that consider the long-term benefits of molecularly targeted therapies in pediatric patients, such as sustained remission and reduced side effects, can provide critical insight into the overall value of these treatments. Such analyses account for the greater lifetime productivity of survivors and can further strengthen the case for increased investment in developing, testing, and approving pediatric cancer therapies.

Despite remarkable gains in pediatric cancer survival over the past five decades, the pace of therapeutic advances for pediatric patients continues to lag behind that of adults, leaving critical gaps in personalized treatments. A renewed emphasis on collaborative innovation—highlighted in emerging research—underscores the transformative potential of cross-sector partnerships in bridging this divide. By prioritizing joint efforts in cancer characterization, target identification, drug discovery, and novel approaches to previously “undruggable” targets, stakeholders can accelerate the development of next-generation therapies tailored to pediatric needs.

Collaborative frameworks not only foster scientific breakthroughs but also lay the groundwork for a more sustainable model of therapeutic advances. Yet, a viable economic infrastructure within the private sector remains elusive. Strengthening partnerships among federal agencies, industry, and philanthropic organizations will be essential to ensure that children and adolescents with cancer benefit equitably from the next generation of lifesaving therapies (73)Das S, et al. (2018) JAMA Oncol, 4: 1274.. Continued and expanded federal investment is essential not only for maintaining US leadership in medical research but also, more urgently, for eliminating the burden of pediatric cancer. Greater investment in pediatric cancer research is essential to securing the long-term survival, health, and productivity of the nation’s youngest patients.

Next Section: Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers Previous Section: A Snapshot of Progress Against Pediatric Cancers in 2025