Screening for Early Detection

In this section, you will learn:

- Research identifying how cancer arises and progresses has led to the development of screening tests that can be used for early detection of cancer and precancerous lesions.

- There are four types of cancer (breast, cervical, colorectal, and prostate) for which screening tests have been used to screen large segments of the U.S. population who are at average risk of developing the cancer being screened for.

- Every person has a unique risk for each type of cancer based on genetic, molecular, and cellular makeup, lifetime exposures to cancer risk factors, and general health.

- We need to develop new strategies to ensure optimal uptake of cancer screening by all.

Research has shown that most cancers arise and progress because of the accumulation of genetic mutations that disrupt the orderly processes controlling cell multiplication and life span (see Understanding Cancer Development). There are numerous factors that cause cells to acquire genetic mutations, including exposure to toxicants in tobacco smoke and UV radiation from the sun, and infection with certain pathogens, such as HPV.

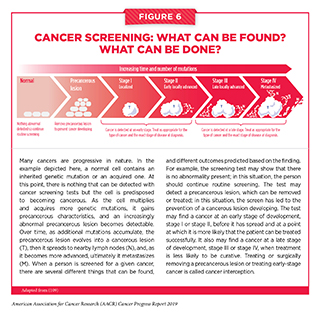

Knowledge of the causes, timing, sequence, and frequency of the genetic, molecular, and cellular changes that drive cancer initiation and development provides opportunities to develop screening tests that can find precancerous lesions or cancers at an early stage of development (see Figure 6). If precancerous lesions are detected, they can be treated or surgically removed before they become cancers. Finding cancer early, before it has spread to other parts of the body, makes it more likely that a patient can be treated successfully. Treating or surgically removing a precancerous lesion or early-stage cancer is called cancer interception.

What Is Cancer Screening and How Is It Done?

Screening for cancer means checking for precancerous lesions or cancer in people who have no signs or symptoms of the cancer for which they are being checked. The aim is to find the abnormality at the earliest possible stage because this increases the likelihood that the patient can be treated successfully, as highlighted by the fact that patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer that is confined to the colon or rectum have a 5-year relative survival rate of 90 percent, while those diagnosed with colorectal cancer that has metastasized have a 5-year relative survival rate of 14 percent (8).

Screening for cancer can be done in various ways, including by using imaging technologies to look for abnormalities inside the body, and by collecting tissue or fluid samples and then analyzing them for abnormalities characteristic of the cancer being screened for (see sidebar on How Can We Screen for Cancer?)

Consensus on Cancer Screening

Screening for cancer has many benefits, but it also has the potential to cause unintended harms (see sidebar on Cancer Screening). This is why cancer screening is not recommended for everyone. Determining whether and for whom a cancer screening test can provide benefits that outweigh the potential harms requires extensive research and careful analysis of the data generated.

In the United States, an independent group of experts convened by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services rigorously evaluates data regarding the benefits and potential harms of cancer screening tests to make evidence-based recommendations about the use of these tests. These volunteer experts form the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). The evidence-based USPSTF recommendations fall into several categories, most prominently, recommendations for screening certain individuals at certain intervals, recommendations against screening, and deciding that there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation.

In addition to considering evidence regarding potential new screening programs, the USPSTF re-evaluates existing recommendations as new research becomes available and can revise the recommendations if necessary. For example, the USPSTF revised its recommendations for cervical cancer screening in August 2018 (139). The revision added HPV testing alone every 5 years as a third screening option for women ages 30 to 65 who are at average risk of developing cervical cancer.

Many professional societies also convene panels of experts to evaluate data regarding the benefits and potential harms of cancer screening tests, and each society makes its own evidence-based recommendations about the use of these tests. Because the representatives on each panel are often different, and different groups give more weighting to certain benefits and potential harms than other groups do, this can result in differences in recommendations from distinct groups of experts. The differences highlight areas in which more research is needed to determine definitively the relative benefits and potential harms of screening, to develop new screening tests that have clearer benefits and/or lower potential harms, or to better identify people for whom the benefits of screening outweigh the potential harms.

Even though there is more consensus than disagreement among cancer screening recommendations from different groups of experts, it can still be challenging for individuals to ascertain for which cancers to be screened and when. One of the most important factors people should consider when making decisions about cancer screening is their own risk of the cancer for which they are being screened. Recommendations for individuals at average risk of developing a certain cancer are different from those for individuals at increased risk of developing the same cancer. Therefore, individuals should consult with their health care providers to develop a cancer screening plan that is tailored to their own unique cancer risks, general health, and tolerance for the potential harms of a screening test.

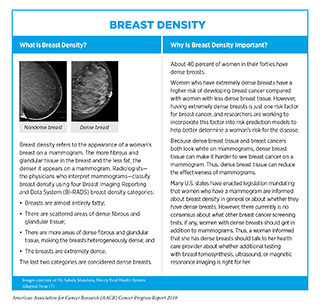

Each person’s unique cancer risks are determined by numerous factors, including genetic, molecular, cellular, and tissue makeup (see sidebar on

Breast Density), lifetime exposures to cancer risk factors, and general health. For individuals at average risk of developing a cancer for which there is a screening test, age and gender are the two main characteristics used to identify those for whom screening is recommended (see sidebar on

Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations for Average-risk Individuals). Age is an important risk factor for cancer because cancer is predominantly a disease of aging – 91 percent of U.S. cancer diagnoses occur among those age 45 and older (8). Thus, a person’s risk for most types of cancer increases with age.

In addition to age, a person’s other risks of developing cancer can change over the course of a lifetime; for example, a woman whose screening mammogram leads to a breast biopsy that reveals certain noncancerous breast conditions, such as lobular carcinoma in situ, is now at increased risk of developing breast cancer and should consider taking measures to reduce her breast cancer risk, such as taking a preventive medicine. Therefore, it is important that individuals maintain a dialog with their health care providers and continually evaluate their cancer screening plans, updating them if necessary.

Some individuals are at increased risk of developing a certain type or types of cancer because of their exposure to modifiable cancer risk factors (see

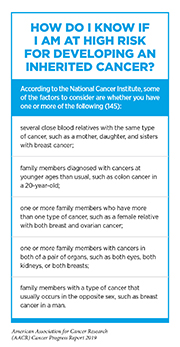

Preventing Cancer: Identifying Risk Factors). For example, people who smoke cigarettes are 15 to 30 times more likely to develop lung cancer than people who do not smoke cigarettes (140) (141). Others are at increased risk because they inherited a cancer-predisposing genetic mutation (see Table 2). People who have a family or personal history of cancer and think that they are at high risk for inheriting such a mutation should consult their health care providers and consider genetic testing (see sidebar on How Do I Know If I Am at High Risk for Developing an Inherited Cancer?). As researchers learn more about inherited cancer risk (142-144), there will be new genetic mutations to test for and changes to the recommendations about who should be offered genetic testing. Thus, it is important that individuals at high risk for inheriting a cancer-predisposing genetic mutation maintain an ongoing dialog with their health care providers and continually evaluate whether genetic testing is available and/or right for them.

It is important to note that there are direct-to-consumer genetic tests that individuals can use without a prescription from a physician, but there are many factors to weigh when considering whether to use one of these tests. Because of the complexities of these tests, the FDA and Federal Trade Commission recommend involving a health care professional in any decision to use such testing, as well as to interpret the results.

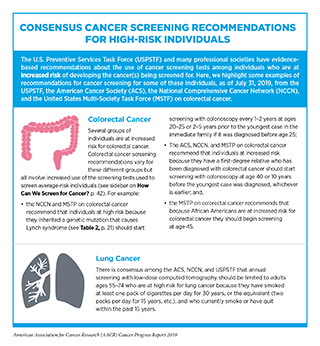

All people who have an increased risk of developing a certain type or types of cancer should consult with their health care providers to tailor risk-reducing measures to their personal situations. Some individuals may be able to reduce their risk by increasing their use of certain cancer screening tests or using cancer screening tests that are not recommended for people who are at average risk for the cancer (see sidebar on

Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations for High-risk Individuals). Others may consider having risk-reducing surgery or taking a preventive medicine, for example, women at high risk for breast cancer may take tamoxifen or raloxifene to reduce their risk (see Table 4, and Supplemental Table 1).

As we increase our understanding of the biology of precancerous and cancerous lesions we will be able to identify new biomarkers and develop new screening tests for more types of cancer (146-147). We will also be able to better tailor cancer prevention and early detection to the individual patient, ushering in a new era of precision cancer prevention (148-149).

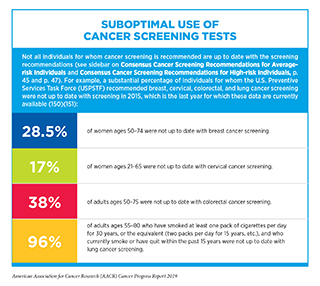

Use of Cancer Screening Is Suboptimal

Even though the benefits of breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancer screening outweigh the potential risks for defined groups of individuals (see sidebars on

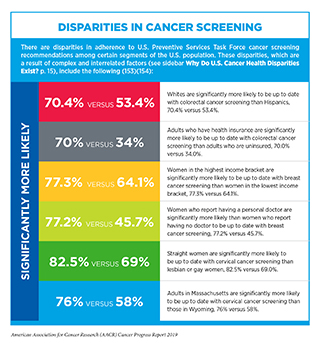

Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations for Average-risk Individuals, and Consensus Cancer Screening Recommendations for High-risk Individuals), many people for whom screening is recommended do not get screened (see sidebar on Suboptimal Use of Cancer Screening Tests) (150) (151). Individuals who are not up to date with cancer screening recommendations are disproportionately found in segments of the U.S. population that are medically underserved (152–153) (see sidebars on Disparities in Cancer Screening, and Which U.S. Population Groups Experience Cancer Health Disparities?).

In addition to suboptimal uptake among those individuals for whom screening is recommended, some people for whom screening is not recommended, such as adults above the recommended age cutoff for a given cancer screening test and those with limiting life expectancy, are screened even though the evidence indicates that the benefits of screening are unlikely to outweigh the potential harms for them (154-156).

The suboptimal use of cancer screening tests and the significant disparities in cancer screening rates among certain segments of the U.S. population highlight the need for new strategies, legislation, and public policies to increase cancer screening awareness, access, and uptake among those for whom screening is recommended, as discussed by Congressman Donald McEachin. Identifying strategies to achieve this goal is an area of intensive research investigation. Numerous studies have shown that colorectal cancer screening rates can be significantly increased by actively reaching out to adults not up to date with screening either by mailing then information about colorectal cancer risk and a stool test or by implementing patient navigation programs that provide individualized assistance to help patients overcome personal and health care system barriers, and to facilitate understanding and timely access to screening (157-158). Regular, high-quality patient – health care provider conversations offer another way to increase awareness and ensure optimal implementation of cancer screening. However, recent research suggests that we need to do much more to increase the frequency and the quality of these conversations (154, 159-160).