- Molecular and Cellular Influences Driving Pediatric Cancers

- Innovative Technologies Decoding Pediatric Cancer Complexities

- Single-cell, Multi-omic, and Spatial Technologies

- CRISPR Gene Editing

- Research Model Systems

- Artificial Intelligence

- Liquid Biopsy

- Shared Data and Collaborations Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research

Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers

In this section, you will learn:

- Pediatric cancers usually arise during early development and exhibit biological features that are distinct from those of adult cancers.

- Compared to adult cancers, pediatric cancers harbor fewer mutations overall and are more often driven by specific mutations or structural changes in DNA that modify the epigenome.

- Changes in the genome, epigenome, developmental pathways, and tumor microenvironment contribute to how pediatric cancers originate, progress, and respond to treatment.

- Innovative technologies, including single-cell and spatial profiling, multi-omics, and CRISPR gene editing, are revealing the hidden complexities of pediatric cancers.

- Large-scale global collaborations and data-sharing initiatives are accelerating discoveries and translating them into safer, more effective therapies that are tailored for pediatric cancers.

- Despite advances in pediatric cancers, scientific and clinical challenges remain, including limited research models and datasets for pediatric cancers, a lack of targeted therapies against most proteins driving pediatric cancers, and treatment-related toxicities that can impact growth, development, and quality of life for children and adolescents.

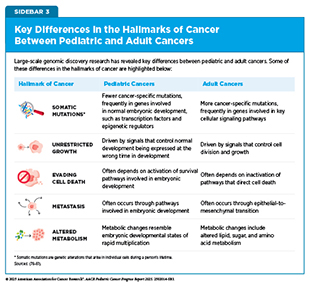

Cancer is a collection of diseases in which some of the body’s cells acquire changes that allow them to grow uncontrollably and spread to other parts of the body. Throughout the course of cancer development, abnormal or damaged cells acquire distinct traits—known as the “hallmarks of cancer”—that set them apart from normal cells. Research in the past few decades has uncovered the unique biological underpinnings of pediatric cancers in children (ages 0 to 14) and adolescents (ages 15 to 19) and the features that distinguish them from adult cancers (see Sidebar 3). Unlike adult cancers, which often result from accumulated genetic damage attributable to normal aging as well as modifiable risk factors, pediatric cancers typically have fewer overall mutations and fewer known links to environmental exposures.

Many pediatric cancers originate during early stages of development, sometimes even before birth, when cells are rapidly dividing and acquiring traits to play specific roles in the body. The alterations that drive pediatric cancers frequently lead to normal developmental pathways being hijacked by cancer cells to drive tumor growth, resulting in tumors that can progress quickly and behave differently from their adult counterparts. Understanding these distinct genomic and biological features is essential for developing therapies that are safe and effective for pediatric cancers.

Large-scale, multidisciplinary pediatric-focused collaborations are generating shared data resources and accelerating the clinical integration of new discoveries, paving the way for more precise diagnoses and tailored treatments for young patients. Advances in pediatric cancer research continue to reveal molecular and cellular changes that shape the initiation and progression of childhood and adolescent cancers. Many of these advances are made possible by innovative technologies that provide new insights into the complex changes in the genome, epigenome, developmental pathways, and tumor microenvironment that drive pediatric cancers.

Molecular and Cellular Influences Driving Pediatric Cancers

Cells store their genetic information in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), a molecule comprising a double helix made of paired chemical bases—adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G)—arranged in repeating units called nucleotides. The entirety of a person’s DNA is called the genome. In human cells, DNA is packaged with proteins called histones into structures known as chromatin, which are further compacted into chromosomes. Each chromosome contains hundreds to thousands of genes, which are segments of DNA that contain the directions for making proteins. Through a process called transcription, these directions are used to make messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), which is then translated to make specific proteins that carry out essential functions in the body.

When the genetic instructions or the processes that interpret them to make protein are altered, the finely tuned molecular and cellular programs that guide normal growth and development can be disrupted, leading to cancer development. These disruptions can stem from changes in the DNA sequence (genetic alterations) or its chemical modifications that control when and how genes are expressed (epigenetic modifications). These changes result in altered proteins or amounts of proteins, which in turn interfere with biological processes that guide cell growth and tissue formation (developmental pathways) as well as interactions with the surrounding tissue environment (tumor microenvironment).

Genetic Alterations

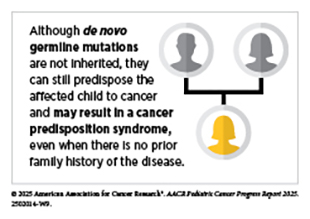

Understanding the genetic alterations that drive pediatric cancers is essential to unraveling cancer development and guiding the discovery of new, more effective therapies. Genetic alterations, also called mutations or variants, can be passed down through the germline or acquired throughout a person’s life. Germline mutations are typically present in every cell in the body and can be inherited from parents or occur de novo—arising at conception or during early embryo development without being inherited—while somatic mutations, which are acquired over an individual’s lifetime, are restricted to selected cells. Whether germline or somatic, pathogenic genetic mutations are those changes in DNA sequence that disrupt normal cellular functions, leading to cancer. For example, pathogenic mutations can activate oncogenes (genes that promote cell growth) or inactivate tumor suppressor genes (genes that restrict cell growth), both of which can contribute to cancer development.

These alterations are classified based on whether they are present in the DNA of germline and/or cancer cells, as well as based on their potential impact on gene and protein function, which can influence disease risk (see Sidebar 4). As researchers continue to uncover the full spectrum of genetic changes in pediatric cancers, their discoveries are reshaping how these diseases are diagnosed, classified, and treated.

Research has revealed that integrating genomic data generated from both somatic alterations in a child’s tumor and germline alterations in the child’s normal tissue can provide powerful insights into pediatric cancer biology. Large-scale sequencing studies have found that over 70 percent of childhood tumors have diagnostic or actionable genetic alterations, including inherited mutations in cancer predisposition genes and somatic changes in developmental pathways, which could help clinicians either diagnose the cancer or identify appropriate treatments (82)Parsons DW, et al. (2016) JAMA Oncol, 2: 616.(83)Wong M, et al. (2020) Nature Medicine, 26: 1742.. Similarly, pan-cancer studies analyzing tumors from children and from adolescents and young adults (AYAs) showed that over half of them carried potentially druggable mutations, and up to 18 percent of pediatric patients had an inherited germline variant predisposing them to cancer (84)Grobner SN, et al. (2018) Nature, 555: 321.(85)Newman S, et al. (2021) Cancer Discov, 11: 3008..

Emerging technologies are expanding our ability to detect a wide spectrum of genetic alterations (see Sidebar 5). For example, researchers using an approach that combines whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and RNA sequencing to analyze paired tumor and normal tissue samples uncovered both large and small genetic alterations in 86 percent of the pediatric cancers sequenced, including clinically relevant variants that would have been missed or not effectively detected using any one sequencing approach alone (85)Newman S, et al. (2021) Cancer Discov, 11: 3008.. Similarly, a study integrating WGS, RNA sequencing, and DNA methylation profiling of paired tumor and normal samples in high-risk pediatric cancer patients identified actionable variants and refined diagnoses (83)Wong M, et al. (2020) Nature Medicine, 26: 1742.. These studies demonstrate the value of combining these technological approaches for comprehensive molecular characterization.

The following sections describe how different genetic alterations contribute to pediatric cancer risk, development, and treatment outcomes.

Germline Variants in Cancer Predisposition Genes

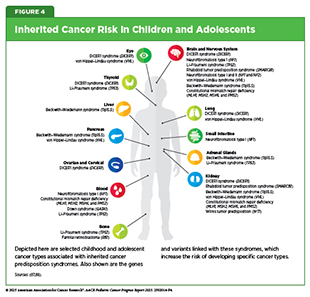

Germline variants in cancer predisposition genes play a critical role in determining the risk of developing pediatric cancer (see Sidebar 4). A recognizable pattern of cancer within families that stems from pathogenic germline variants in cancer predisposition genes is often classified as a cancer predisposition syndrome (CPS) (see Figure 4). For example, at least 13 CPSs are now known to increase the risk of developing pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), including both overt syndromes with recognizable features and covert syndromes lacking clear clinical features (see Pediatric Cancer Predisposition and Surveillance) (86)Stoltze U, et al. (2025) Leukemia, 39: 1031..

Up to 18 percent of all pediatric cancer cases are attributed to pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variants in cancer predisposition genes, including those in the TP53, BRCA2, NF1, and RB1 genes (87)Kratz CP (2025) Nat Rev Cancer, 25: 109.(89)Zhang J, et al. (2015) N Engl J Med, 373: 2336.. Genome-wide association studies and sequencing efforts have identified recurrent germline mutations that increase risk for specific pediatric cancers. For example, alterations in the IKZF1, PAX5, and ETV6 genes increase risk for ALL, the most common childhood cancer; alterations in the ALK and PHOX2B genes are linked to neuroblastoma, the most common solid tumor in children arising outside the brain; and alterations in DNA damage repair genes—such as FANCA, FANCC, or ATM—increase the risk for Ewing sarcoma and leukemias (90)Douglas SPM, et al. (2022) Sci Rep, 12: 10670.(91)Kamihara J, et al. (2024) Clin Cancer Res, 30: 3137.(92)Gillani R, et al. (2022) Am J Hum Genet, 109: 1026..

These inherited alterations can shape the biology of pediatric cancers and influence clinical outcomes. For example, children with Down syndrome—a genetic condition caused by having an extra copy of chromosome 21 in some or all of the body’s cells—who are diagnosed with a rare subtype of acute myeloid leukemia have vastly better outcomes than children without Down syndrome with the same subtype of leukemia (93)Taub JW, et al. (2017) Blood, 129: 3304.. This is due to the unique biology of Down syndrome–associated myeloid leukemia, which is more sensitive to chemotherapy.

Pediatric colorectal cancer is extremely rare, and children often experience delayed diagnosis and poor clinical outcomes due to nonspecific clinical symptoms and limited awareness among clinicians. Findings from a small clinical study showed that CPSs caused by inherited mismatch repair deficiency—a condition resulting from mutations in genes responsible for correcting mistakes made when a cell makes copies of its DNA—underlie a subset of pediatric colorectal cancer cases, underscoring the need for earlier detection and diagnosis to improve outcomes in children with this rare disease (94)Shen Q, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31569..

Recent research has also demonstrated that an understudied class of rare germline variants, germline structural variants—which are large genomic rearrangements that involve 50 or more nucleotides—can increase the risk of developing pediatric solid tumors like neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma (95)Gillani R, et al. (2025) Science, 387: eadq0071.. These structural variants disrupted critical genes, including those involved in DNA repair and normal tissue development, and many occurred de novo or were inherited from unaffected parents. Although germline structural variants contribute to only a minority of pediatric cancer cases, they represent an important and previously underrecognized form of inherited cancer risk.

These examples highlight how germline mutations can influence cancer risk, disease progression, and response to treatment, emphasizing the importance of integrating germline testing into routine pediatric cancer care. Importantly, identifying a germline mutation can guide ongoing follow-up for the child and adolescents, and inform genetic counseling and testing for family members (see Pediatric Cancer Predisposition and Surveillance).

Somatic Mutations

Somatic mutations are genetic alterations that arise in individual cells during a person’s lifetime (see Sidebar 4). In pediatric cancers, these mutations typically occur early in development and drive tumor formation by disrupting genes that control cell growth, differentiation, or DNA repair. Somatic alterations range from small single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions or deletions (indels) to large structural variants (SVs), including chromosomal translocations, inversions, and complex genomic rearrangements. Both large and small alterations may contribute to the genetic complexity of pediatric tumors and influence cancer development.

Somatic mutations can also play a role in the development of cancer in children and adolescents with inherited CPS (see Figure 4), as described by the “two-hit hypothesis.” This model suggests that even when a mutation is present from birth (first hit), some malignancies develop only after a second pathogenic mutation (second hit) is acquired in the remaining healthy copy of that gene. Recently, a study in children with the neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) predisposition syndrome found that second hits in the NF1 gene can occur in normal tissues, not just in tumors. These second hits were found in normal tissues throughout the body, showing that cells can acquire cancer-related mutations without immediately progressing to tumors, underscoring the complexity of tumor initiation (96)Oliver TRW, et al. (2025) Nat Genet, 57: 515..

Somatic mutations in pediatric tumors often show unique features compared to those in adults. A large-scale WGS analysis of 785 pediatric tumors across 27 cancer types revealed that fewer SNVs and indels drive cancers in children than in adults, but when they do act as drivers of pediatric cancers, they often disrupt biological processes that are distinct from those in adults (see Sidebar 3) (97)Thatikonda V, et al. (2023) Nat Cancer, 4: 276..

Age-based genomic comparisons further underscore how pediatric and adult cancers are driven by distinct mutational profiles. A study in hematologic malignancies in children, young adults, and older adults reinforced a general feature of pediatric cancers—children and young adults tend to have lower tumor mutational burdens but more frequent oncogenic gene fusions and copy number alterations compared to older adults. Several mutations, such as those in the NRAS, KRAS, and WT1 genes, were more prevalent in children and young adults, whereas TP53 and DNMT3A mutations were more common in older adults (98)Yang X, et al. (2024) Commun Biol, 7: 1630.. These findings emphasize the need for tailoring genomic profiling and treatment strategies to distinct age-related genomic features.

Large-scale genomics studies of pediatric B-cell ALL (B-ALL) have defined more than 20 molecular subtypes, each with specific germline and somatic alterations that shape disease biology and influence clinical outcomes (99)Brady SW, et al. (2022) Nat Genet, 54: 1376.. T-cell ALL (T-ALL) has historically been less well characterized, but recent research has identified biologically distinct subtypes of pediatric T-ALL based on alterations in segments of DNA that encode proteins (coding regions) as well as the parts that do not encode proteins but may control how certain genes are turned on and off (non-coding regulatory regions). In a study of over 1,300 pediatric T-ALL cases, researchers identified 15 molecular subtypes, each with distinct genomic drivers, gene expression patterns, and clinical outcomes. Notably, 60 percent of alterations driving leukemia development were in non-coding regions, many of which hijacked mechanisms that control normal gene activity (100)Polonen P, et al. (2024) Nature, 632: 1082.. These advances are enabling new ways to assess and classify the risk of pediatric cancers and help clinicians personalize therapies using such classification (see Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment).

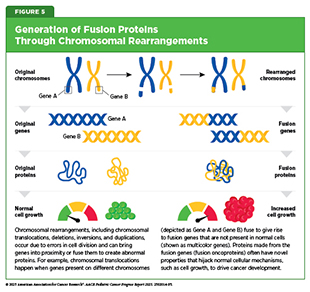

Large SVs—such as chromosomal rearrangements, gene fusions, and complex rearrangements—represent a distinct category of genomic alterations that drive pediatric tumor development. These large-scale events can rewire gene regulation, create fusion proteins with abnormal activity, and disrupt tumor suppressor genes. Advances in DNA and RNA sequencing technologies and structural variant detection have uncovered the influence of SVs across many pediatric cancer types.

Cancer-causing gene fusions result from chromosomal rearrangements and constitute a class of genetic alterations in which two genes, present on two different chromosomes (more common) or on the same chromosome (less common), fuse to make a gene that is not present in normal cells and, in turn, a unique protein with altered function known as a fusion oncoprotein. These fusions occur across a wide range of pediatric cancers and are known drivers of cancer development (see Figure 5).

Chromosomal rearrangements frequently involve genes encoding either specialized enzymes that are present on the surface of the cell and regulate cell growth, migration, and survival, or specialized proteins called transcription factors that bind to DNA and turn genes on or off. The resultant fusion oncoproteins act as potent cancer drivers. Cancers driven by some fusions, such as those involving ABL or NTRK, can be effectively targeted with matched therapies, but other fusions, such as EWSR1::FLI1 in Ewing sarcoma or PAX3::FOXO1 in rhabdomyosarcoma, remain difficult to target directly (101)Liu SV, et al. (2025) Signal Transduct Target Ther, 10: 111..

Specific SVs can also be used to assess risk and predict treatment responses in pediatric cancer. The IKZF1 gene encodes a protein that plays a critical role in normal blood cell development, including guiding B-cell maturation. A recent study of over 680 children with B-ALL indicated that certain large deletions in the IKZF1 gene are strongly associated with relapse. These deletions were most common in B-ALL cases with BCR::ABL1 gene fusions and in BCR::ABL1–like (or Philadelphia chromosome–like) subtypes, two high-risk genetic forms of the disease, often with available drugs targeting the gene fusion (102)Wang’ondu RW, et al. (2025) Leukemia, 39: 1595..

Large SVs that involve oncogene amplifications can drive uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumor development. The MYCN gene encodes a member of the MYC protein family that plays a critical role in both normal development and tumor growth. In neuroblastoma, the most common type of extracranial solid tumor in children, amplification and overexpression of the MYCN gene have emerged as an indicator of high-risk disease (103)Bartolucci D, et al. (2022) Cancers (Basel), 14.. Indeed, amplification and overexpression of MYCN, ALK, and other genes have also been shown to be predictive of a poor outcome in pediatric brain tumors, retinoblastoma, sarcomas, and other solid tumors. Although it remains difficult to target the MYCN protein directly, emerging strategies, such as destabilizing the protein or interfering with the regulatory networks and molecular partners that control its function, offer promising therapeutic opportunities (see Evaluating Novel Targets and Innovative Therapeutic Strategies) (104)Fernandez Garcia A, et al. (2025) Front Oncol, 15: 1584978..

Complex genomic rearrangements are large structural changes in DNA that can disrupt normal genome organization and drive cancer development. Examples include chromothripsis—a phenomenon in which a chromosome shatters and is pieced back together in the wrong order—and amplification of extrachromosomal DNA, which are circular DNA fragments that exist outside chromosomes and can drive high oncogene expression and genomic instability. In a recent study, researchers using WGS from 120 primary tumors showed that 47 percent of pediatric solid tumors harbor complex genomic rearrangements that are linked to worse clinical outcomes (105)van Belzen I, et al. (2024) Cell Genom, 4: 100675..

Both small and large somatic alterations shape the biology and, in turn, the clinical landscape of pediatric cancers. This knowledge also emphasizes the need for more comprehensive characterization of pediatric cancer genomes to improve diagnostic precision and guide therapeutic care for each patient. Emerging technologies and advances in molecular profiling will be essential to guide the development of more precise, age-tailored treatment strategies for children and adolescents with cancer.

Epigenetic Modifications

Epigenetic modifications are chemical changes that regulate how genes are expressed without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These modifications involve the addition or removal of chemical marks on DNA and modifications to the sequences of histones—the proteins that package chromosomal DNA into chromatin. In healthy cells, both epigenetic modifications and chromatin packaging tightly regulate gene expression, but in cancer this regulation is disrupted. Unlike adult tumors, which tend to harbor high mutational burdens, pediatric cancers are often driven by disruptions in the epigenetic machinery that controls gene activity.

One common type of epigenetic modification is DNA methylation, in which methyl groups are added to specific regions of the genome to regulate whether nearby genes are turned on or off. Recently, researchers studying how germline SVs influence tumor DNA methylation across more than 1,200 pediatric brain tumors have demonstrated that these alterations can significantly influence the epigenetic landscapes in important parts of the DNA that regulate gene activity, altering the expression of cancer-related genes and affecting clinical outcomes (106)Chen F, et al. (2025) Nat Commun, 16: 4713..

Characterization of DNA methylation patterns has emerged as an important biomarker for diagnosis and risk stratification in pediatric cancers (see Sidebar 5). The World Health Organization’s 2021 guidelines established DNA methylation arrays as an important diagnostic tool for pediatric brain tumors, providing more precise tumor classification than traditional tissue analysis and reducing unclear diagnoses (107)International Agency for Cancer Research. Central Nervous System Tumours. Accessed: September 30, 2025.. Methylation profiles are increasingly being coupled with artificial intelligence (AI), shifting the diagnostic standard for brain tumors, such as medulloblastoma and gliomas, and illustrating how AI is being integrated into pediatric oncology to enhance diagnostic accuracy (see Artificial Intelligence).

In pediatric leukemias, DNA methylation-based classifiers use patterns of DNA methylation to group patients into biologically or clinically meaningful subtypes (108)Schafer Hackenhaar F, et al. (2025) Blood, 145: 2161.(109)Steinicke TL, et al. (2025) Nat Genet, 57: 2456. and has entered routine clinical practice for juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, a rare forms of childhood leukemia (110)Schonung M, et al. (2021) Clin Cancer Res, 27: 158.. For T-ALL, which had defied genomic classifiers, methylation profiling significantly improved prognosis when combined with an assessment of minimal residual disease (MRD), which detects a very small number of cancer cells in the body. Subtypes determined by this classifier were associated with distinct transcriptomic, genomic, and cellular features, suggesting different pathways that contribute to leukemia and offering opportunities to refine treatment decisions (108)Schafer Hackenhaar F, et al. (2025) Blood, 145: 2161..

Epigenetic regulators are being explored as therapeutic targets, given their importance in driving pediatric cancers, including fusion protein–driven cancers. For example, in January 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the molecularly targeted therapeutic tazemetostat for the treatment of pediatric patients age 16 years and older with a certain type of sarcoma. Tazemetostat works by targeting the epigenetic regulator EZH2 and preventing it from adding methyl groups to histones (see Expanding Treatment Options for Patients with Solid Tumors). Additionally, in November 2024, FDA approved the small molecule revumenib for pediatric patients 1 year and older with acute leukemia that has relapsed or stopped responding to standard treatments. Revumenib disrupts the binding of a protein encoded by the KMT2A gene, which plays a role in normal blood cell development through epigenetic regulation of gene expression (see Adding Precision to the Treatment of Leukemia). Additional epigenetic drug classes, such as DNA hypomethylating agents and histone deacetylase inhibitors, are also under investigation in pediatric settings and may further expand therapeutic strategies that modulate the epigenome.

As the field advances, integrating epigenomic profiling into clinical workflows may allow for earlier detection, refined prognosis, and personalized therapies targeting the epigenetic underpinnings of pediatric cancers.

Developmental Pathways Gone Awry

Genetic and epigenetic alterations often drive pediatric cancers by functionally rewiring or arresting normal developmental pathways. Pediatric cancers often arise from cells at specific embryonic or fetal developmental stages in which key pathways controlling tissue growth and differentiation have been disrupted (see Sidebar 6) (25)Chen X, et al. (2024) Nat Rev Cancer, 24: 382..

In the developing body, immature stem-like cells normally keep dividing until they develop into fully mature cells with specialized roles. Recent research has revealed that some cancers take control of and block the processes that normally guide cells into their final, specialized roles. In diffuse midline gliomas (DMGs), a fast-growing, highly aggressive brain cancer, a mutation in the histone protein known as H3K27M changes the way DNA is packaged, whether genes are turned on or off, and how much they are expressed. A recent study showed that this mutation locks cells in an immature, proliferative state that fuels cancer growth, highlighting a potential therapeutic opportunity for this pediatric brain cancer (117)Lagan E, et al. (2025) Mol Cell, 85: 2110..

Disrupted developmental pathways can also intersect with the nervous system to fuel tumor growth. During normal brain development, nerve cells called GABAergic neurons signal to immature brain cells to support their growth. In DMGs, the same signals are hijacked by tumors to accelerate growth and progression. This effect is further accelerated in the presence of lorazepam (Ativan)—a common sedative that works by enhancing GABA signaling. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the unique tumor–nervous system interactions that drive DMG progression to enable the development of effective and safe therapeutic strategies (118)Barron T, et al. (2025) Nature, 639: 1060..

New therapeutic advances have emerged that target neuronal signaling. In August 2025, FDA approved dordaviprone for children age 1 year and older with DMG harboring an H3K27M mutation. Dordaviprone works by blocking dopamine receptors, components of a normal neuronal signaling pathway essential for brain development and function, that tumor cells can hijack to promote their growth and survival (see Personalizing the Treatment of Brain Tumors). Because pediatric cancers often hijack normal developmental pathways to promote growth, understanding these mechanisms provides critical opportunities to develop additional therapies that disrupt tumor-supportive signaling and restore developmental programs.

Importantly, our ability to discern these mechanisms often requires investigating specific cancer drivers in model systems or using patient-derived models. However, few models exist for studying pediatric cancers because of their rare nature, which hinders our ability to mechanistically evaluate the cancer driving events and devise approaches to address the dysregulated pathways.

Tumor Microenvironment

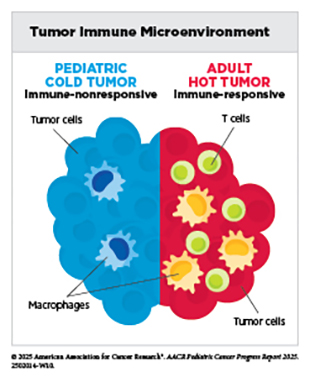

Complex interactions between cancer cells and their surrounding environment, known as the tumor microenvironment (TME), contribute to disease progression. The TME—composed of cancer and supportive, non-cancer (immune, stromal) cells, blood vessels, signaling molecules, and structural components—plays a critical role in all cancers, including pediatric cancer, by influencing tumor initiation, growth, and response to treatment. Pediatric TMEs are shaped by developmental stage, unique immune system characteristics, and tumor-intrinsic features, such as specific mutations, epigenetic changes, altered signaling, and metabolic rewiring.

Research comparing pediatric cancers with adult cancers has demonstrated that the TME is greatly influenced by a patient’s age. For example, the TME in children and AYAs with classical Hodgkin lymphoma often exhibits patterns that are distinct from those in older adults, including differences in cellular composition and cell–cell signaling networks that support malignant cell growth and influence treatment response (119)Aoki T, et al. (2025) Front Oncol, 15: 1515250.. These differences underscore why diagnostic, prognostic, and treatment approaches designed for adults may not always work in children, and those designed for children may not be effective in adults, highlighting the need for age-tailored strategies to target the unique TME in pediatric patients.

Within the TME, the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) refers to the network of immune cells and immune-modulating factors that interact with the tumor. The TIME can shape how pediatric cancers develop and respond to treatments, and a deeper understanding of these processes is essential for advancing effective immunotherapies for young patients.

In a recent study, immune profiling in 191 children with diverse solid tumors showed that certain tumor types—such as neuroblastoma, Wilms tumors, liver tumors, lymphomas, and retinoblastomas—share systemic immune characteristics, suggesting that immune markers and treatment approaches could be applied across certain cancer types (120)Chen Q, et al. (2025) Cell, 188: 1425..

Advanced technologies that allow analyses of single cells in their normal spatial context inside tissues and tumors are revealing how cancer treatments reshape the TIME. In high-risk neuroblastoma, 22 patients analyzed before and after chemotherapy showed significant shifts in tumor and immune cell subpopulations, with a reduction of certain fast-growing tumor cells but an increase in certain immune cells that weaken the immune response (121)Yu W, et al. (2025) Nat Genet, 57: 1142.. In pediatric high-grade gliomas, chemotherapy and radiation reduced certain pro-inflammatory immune cells, reshaping the TIME. When patients received subsequent immunotherapy, the altered TIME had a disproportionate number of immune-suppressing T cells, which may limit long-term success of the treatment (122)LaBelle JJ, et al. (2025) Cell Rep Med, 6: 102095.. These findings emphasize that an initial therapy can rewire the TME in ways that may influence the success of subsequent treatments.

The pediatric TME/TIME can act as both a barrier to and an opportunity for successful cancer treatment. By uncovering how these environments develop, support tumor growth, and evolve with treatment, researchers can design more precise interventions. Integrating emerging single-cell, spatial, and multi-omic technologies will deepen our understanding of pediatric biology and accelerate the translation of these insights into more effective, tailored therapies for pediatric cancers.

Innovative Technologies Decoding Pediatric Cancer Complexities

Innovative technologies are transforming the way researchers study pediatric cancer. WGS and WES are expanding our ability to uncover genomic features that provide information on likely outcomes, therapeutic targets, and germline predisposition in children and adolescents (85)Newman S, et al. (2021) Cancer Discov, 11: 3008.. In addition, scientific breakthroughs like AlphaFold—which earned David Baker, PhD, John M. Jumper, PhD, and Demis Hassabis, PhD, the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for leveraging AI to predict the three-dimensional (3D) structure of proteins—are helping researchers better understand the altered structures of proteins resulting from pathogenic variants that are associated with pediatric cancers, opening new paths to drug development (123)Callaway E (2024) Nature, 634: 525..

Tumor heterogeneity describes the differences that can exist between tumors arising in the same tissue type across different individuals as well as among multiple tumors or cells in the same tumor within an individual patient when the cancer evolved or spread. Single-cell, multi-omic, and spatial profiling technologies are uncovering previously underappreciated tumor heterogeneity, including differences in cell types and their expression of gene variants, deepening insights into pediatric cancer development.

Gene editing tools such as CRISPR are clarifying how specific genetic changes drive disease, knowledge that can reveal new therapeutic targets. Advanced model systems are capturing the unique genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental characteristics of pediatric cancers. AI-based tools are integrating complex imaging, genomic, and clinical data to enable earlier diagnosis and more accurate tumor classifications. Liquid biopsy, which analyzes cancer-derived material circulating in blood, urine, or other body fluid, is offering a minimally invasive way to monitor cancers in real time, enabling earlier detection, treatment response monitoring, and timely relapse intervention.

The knowledge gained from these technologies is reshaping both the research landscape and the future of pediatric cancer care, paving the way for more personalized, less toxic therapies.

Single-cell, Multi-omic, and Spatial Technologies

Single-cell, multi-omic, and spatial technologies (see Sidebar 5) are allowing researchers to better understand the biology of pediatric cancers. These cutting-edge tools can trace cancer development to its earliest stages by capturing the diversity of cell types and states within tumors and their microenvironments (see Tumor Microenvironment), offering insights into how pediatric cancers evolve, recur or metastasize, and respond to treatment.

Using these technologies, researchers analyzed over 540,000 individual cells from 159 pediatric leukemia cases and healthy bone marrow samples to build a comprehensive single-cell atlas—a detailed map indicating what types of cells are present and how they behave. This effort identified a nine-gene–signature that may reflect common features of malignant transformation across diverse genetic subtypes of pediatric leukemia (124)Mumme HL, et al. (2025) Nat Commun, 16: 4114.. The resulting Pediatric Single-cell Cancer Atlas is an open-access resource enabling researchers to investigate gene expression, cell types, and potential biomarkers in pediatric leukemias. In a similar study, researchers used single-cell transcriptomic technologies to identify gene signatures that reflect shared mechanisms of malignant transformation and predict poor outcomes and resistance to standard chemotherapy across diverse pediatric leukemia subtypes (125)Chen C, et al. (2025) Blood, 145: 2685..

Multi-omic technologies are also helping researchers uncover how developmental lineages shape disease progression and the mechanisms that influence treatment response in pediatric leukemia. Single-cell transcriptomics and epigenomic studies are revealing the developmental trajectories cells take as they mature and identifying small populations of cells that display characteristics similar to stem cells—cells from which other types of cells develop—across multiple leukemia subtypes (126)Leo IR, et al. (2022) Nat Commun, 13: 1691.(127)Chen C, et al. (2022) Blood, 139: 2198.(128)Xu J, et al. (2025) Nat Cancer, 6: 102.(129)Iacobucci I, et al. (2025) Nat Cancer, 6: 1242.. Integration of transcriptomic, proteomic, and drug sensitivity data resulted in a better understanding of subtype-specific differences in cancer biology and treatment response. These studies revealed distinct molecular features across subtypes and identified potential therapeutic candidates through drug sensitivity profiling.

By combining single-cell and spatial technologies, researchers are also gaining new insights into pediatric solid tumors. For example, researchers identified a transient cell state that is unique to high-risk neuroblastoma and associated with poor outcomes. This state is shaped by epigenetic changes and the resulting cell signaling that influences the ability of cells to change their identity or function over time to help them survive, grow, or resist treatment (130)Xu Y, et al. (2025) Dev Cell.. In another study, researchers traced the timing of genetic events in an aggressive subtype of medulloblastoma to identify when and how key alterations emerge during tumor growth. The findings show that large-scale chromosomal changes initiate tumor growth early in fetal development, while single-gene alterations arise later, contributing to disease progression and resistance to therapy (131)Okonechnikov K, et al. (2025) Nature, 642: 1062.. These discoveries reveal how advanced molecular tools can uncover features of tumor development, shedding light on why some pediatric cancers become more aggressive.

CRISPR Gene Editing

CRISPR is a powerful and versatile gene editing tool that allows researchers to precisely modify DNA. Researchers have harnessed CRISPR to deepen our understanding of mechanisms that drive human diseases and explore new ways to treat them. For example, CRISPR can be used in model systems to re-create genetic mutations to understand how they affect the body, fix or replace faulty genes, add tags to track how genes behave, turn genes on or off without changing the DNA itself, or engineer immune cells to fight disease.

Traditional CRISPR editing tools are made up of two parts, a programmable RNA guide that can find a specific site in the DNA and a Cas protein that acts like molecular scissors to cut both strands of DNA at that site. After DNA has been cut, the cell’s natural DNA repair processes can be harnessed to make changes with high precision and accuracy. These innovative tools are supporting a new era of discovery in pediatric cancer research. While pediatric cancers often harbor fewer mutations than adult tumors, they remain genetically complex and biologically distinct.

High-throughput CRISPR functional genomic assays are being applied to address one of pediatric oncology’s most persistent challenges: how to interpret variants of unknown significance, variants whose role in the disease is unclear and therefore cannot be understood in terms of their clinical impact (see Sidebar 4). In many cases, comprehensive DNA sequencing, such as WGS or WES, reveals rare or novel somatic or germline variants in cancer-relevant genes with unclear clinical significance. These are typically variants that change one amino acid for another, but without an obvious impact on the resulting protein.

Using CRISPR-based screening to functionally test all possible variants of unknown significance in known cancer predisposition genes can improve how genetic findings can be interpreted, guide clinical decision-making, and help determine which children or adolescents may benefit from enhanced surveillance or targeted interventions (132)Mardis ER (2025) Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet, 26: 279.. In a recent study, researchers used CRISPR to investigate germline variants in the BARD1 gene, which is associated with increased risk of neuroblastoma, and identified a subset that exhibited compromised DNA repair, widespread genomic instability, and heightened sensitivity to DNA-damaging therapies. These findings help clarify how inherited genetic variants contribute to pediatric cancer and may lead to their inclusion in clinical reporting of cancer predisposition, resulting in enhanced surveillance (133)Randall MP, et al. (2024) J Natl Cancer Inst, 116: 138..

In cancer, gene dependencies occur when cancer cells rely on specific genes for their survival and growth, making those genes potential therapeutic targets. Researchers using large-scale CRISPR screening have enabled the development of a pediatric cancer dependency map, revealing that pediatric cancers exhibit distinct gene dependencies from those in adult cancers (134)Dharia NV, et al. (2021) Nat Genet, 53: 529.. These results reveal new therapeutic vulnerabilities unique to childhood and adolescent cancers and emphasize the need for leveraging these vulnerabilities to develop drugs specifically against pediatric cancers.

CRISPR has also been used to find effective drug combinations for high-risk subtypes of neuroblastoma, for which standard therapies often fail. By mapping how the loss of a specific gene changes the way cells respond to drugs across more than 94,000 gene–drug–cell line combinations, researchers identified new drug combinations, including inhibition of the DNA repair gene PRKDC, that dramatically improved sensitivity to doxorubicin, a commonly used chemotherapy drug (135)Lee HM, et al. (2023) Nat Commun, 14: 7332..

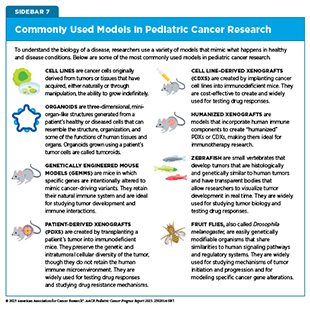

Research Model Systems

Model systems enable researchers to investigate how pediatric tumors develop, test new therapies, and explore resistance mechanisms before moving into clinical trials (see Sidebar 7). By capturing the genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental characteristics of pediatric cancers, model systems accelerate the translation of laboratory discoveries into safer, more effective treatments (136)Amatruda JF (2021) Dis Model Mech, 14..

Traditional cell line cultures, in which cancer cells grow as flat monolayers on plastic, offer a simple and accessible way to study cancer biology but often fail to replicate the complex architecture and microenvironment of patient tumors. To address these limitations, researchers are increasingly using 3D culture models to more closely re-create the architecture, cell–cell interactions, and microenvironmental cues of the original tumor.

In preclinical pediatric cancer research, organoids—miniature organ-like structures grown from a patient’s own cells—are enabling studies of patient-derived tissues in 3D systems that retain genetic, histologic, and molecular features. These models can also capture cellular diversity and tumor heterogeneity. For example, by co-culturing 3D models with immune or stromal cells, the TIME can be more closely replicated (137)Polak R, et al. (2024) Nat Rev Cancer, 24: 523.. Tumoroids, sometimes referred to as cancer organoids, are 3D models derived from patient tumor cells that self-organize into multicellular structures that retain multi-omic characteristics of the original tumor (138)Kim SY, et al. (2025) Trends Cancer, 11: 665.. Pediatric cancer organoids are a valuable tool for modeling tumor biology and studying how these cancers respond to treatment.

Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) are widely used for experimentally modeling human tumors and evaluating new therapies in mice. Some models incorporate human immune components to create “humanized” PDXs. These models can better reflect pediatric TIME interactions and provide a powerful platform for evaluating immunotherapeutics. The Individualized Therapy for Relapsed Malignancies in Childhood program, led by the Hopp Children’s Cancer Center and the German Cancer Research Center, shows how such models are being integrated into precision oncology. Within this effort, a multinational phase I/II clinical trial is evaluating novel immunotherapy combinations in children with high-risk cancers, using PDXs in parallel to understand how well these models predict drug response (139)van Tilburg CM, et al. (2020) BMC Cancer, 20: 523..

Genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) allow for investigations into the molecular underpinnings of pediatric cancers by introducing specific cancer-driving mutations in mice to study the effect of a single mutation or the impact of an altered signaling pathway. GEMMs carrying germline mutations that mirror predisposition syndromes have been used to understand how inherited genetic changes drive tumor initiation, why they arise in specific tissues, and how these cancers progress in children (140)Biswas K, et al. (2023) Cancer Sci, 114: 1800.. Additionally, researchers have used GEMMs to recapitulate the histologic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic features of certain pediatric cancers while revealing profound variations within the same tumor as well as maturation patterns specific to cell lineage (141)Schoof M, et al. (2023) Nat Commun, 14: 7717..

Some of the most powerful applications of model systems emerge when multiple research models are integrated to study disease mechanisms and treatment vulnerabilities. For example, researchers used organoids, PDXs, and GEMMs to investigate a key tumor-driving pathway in medulloblastoma and tested a novel treatment strategy targeting therapeutic vulnerabilities (142)Li Y, et al. (2025) Nat Commun, 16: 1091.. This multi-model strategy shows how integrating different research tools can accelerate discovery and translation into targeted treatments for children with aggressive cancers.

Collectively, these model systems form the foundation for translating discoveries in pediatric cancer biology into effective treatments. Initiatives such as the Pediatric Preclinical In Vivo Testing (PIVOT) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) are building on this foundation. The PIVOT Program is systematically evaluating promising agents using rigorously characterized preclinical models to accelerate the development of effective therapies for pediatric cancers (143)National Cancer Institute. Division of Cancer Treatment & Diagnosis. NCI Pediatric Preclinical In Vivo Testing (PIVOT). Accessed: August 31, 2025.. By combining innovative model systems with coordinated testing efforts, the pediatric cancer research community can continue to accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapies.

Artificial Intelligence

AI is rapidly emerging as a transformative technology across the cancer care continuum, offering unprecedented opportunities to integrate complex imaging, genomic, and clinical data for improved patient care. In pediatric cancer, progress is restricted by the rarity of these diseases. As a result, datasets available to train robust AI models are much smaller, limiting performance, generalizability, and speed of translation into the clinic. Still, by leveraging machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, AI can identify subtle patterns that may be imperceptible by traditional approaches, enabling earlier diagnosis, more accurate tumor classification, and better-informed treatment selection (144)eClinicalMedicine (2024) EClinicalMedicine, 72: 102705.(145)Wen S, et al. (2024) EJC Paediatric Oncology, 4: 100197..

In diagnostics, AI is already demonstrating its potential to enhance the interpretation of histology and imaging data. For example, DL models trained on harmonized, multi-institutional libraries of pediatric sarcoma histology images achieved high accuracy in classifying tumor subtypes, including rare cases that can be difficult to identify using conventional methods (146)Thiesen A, et al. (2025) Cancer Research, 85: 2423.. Similarly, DL approaches applied to serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of children with gliomas predicted tumor recurrence up to a year in advance, enabling more tailored surveillance and potentially reducing unnecessary imaging (see New Frontiers in Surveillance for Children With Cancer Predisposing Syndromes) (147)Tak D, et al. (2025) NEJM AI, 2..

AI has also advanced molecular profiling, particularly through ML-driven DNA methylation–based classification of certain pediatric tumors. In pediatric central nervous system (CNS) tumors, such tools have improved diagnostic accuracy, particularly for difficult-to-classify brain tumors like medulloblastoma and high-grade gliomas, and in some cases could improve prognosis and influence treatment decisions compared to conventional histopathology-based grading alone (148)Lebrun L, et al. (2025) Sci Rep, 15: 2857.(149)Sturm D, et al. (2023) Nat Med, 29: 917.. Models that enable rapid molecular profiling are also emerging, making it possible to classify brain tumors based on sequencing and methylation signatures in less than an hour, or to provide tumor classification with detailed genetic and epigenetic information within 1 day. Similar ML approaches have been developed for cancers such as soft tissue and bone sarcomas, aiding diagnosis even when typical genetic markers are absent (150)Koelsche C, et al. (2021) Nat Commun, 12: 498.. These applications can potentially offer broad accessibility to tumor profiling, even in settings with limited resources, and can guide surgical decisions and enable faster, more personalized treatment planning (151)Brandl B, et al. (2025) Nat Med, 31: 840.(152)Patel A, et al. (2025) Nat Med, 31: 1567..

Beyond tumor classification, AI-enabled integration of structural and functional genomics is revealing new biological insights into pediatric cancers. In a recent study, ML was used to merge large-scale protein interaction data with high-resolution cell imaging, creating detailed maps of the human cell. Researchers applied these maps to genomic data from 772 pediatric tumors across 18 cancer types, which assigned unexpected functions to 975 proteins and identified numerous proteins not previously recognized as pediatric cancer drivers (153)Schaffer LV, et al. (2025) Nature, 642: 222.. These multilayered maps provide a valuable tool for understanding pediatric cancer genomes and demonstrate how AI can connect basic molecular discoveries to new therapeutic targets.

AI applications in pediatric cancer research and care have the potential to enable early detection, deliver more accurate diagnoses, and provide deeper insights into tumor biology. However, the impact of these applications will depend on overcoming challenges such as limited pediatric datasets, model generalizability, and ethical considerations, as well as demonstrating their effectiveness through large clinical trials to determine if they improve outcomes before they can be integrated into practice.

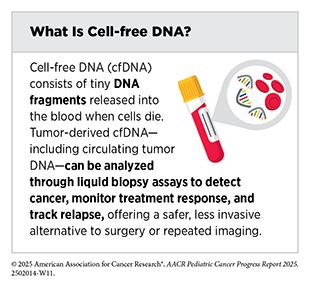

Liquid Biopsy

Liquid biopsy analyzes cancer-derived material circulating in the body and has the potential to transform pediatric oncology, offering a minimally invasive way to capture real-time molecular information about a child’s cancer. By detecting and analyzing tumor-derived materials—including circulating tumor cells and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)—in blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), liquid biopsies can overcome many limitations of traditional tissue biopsies, including limited tissue availability, heightened risks from invasive procedures, and challenges associated with repeated sampling over the course of therapy. Thus, liquid biopsies could enable earlier diagnosis, more precise risk stratification, dynamic monitoring of treatment response, MRD detection, and relapse prediction. While applications for this technology are more advanced in adult cancers, continuing to develop approaches specific to pediatric cancers is essential to ensure that children and adolescents equally benefit from these innovations.

Researchers have recently developed a method that could perform genomic characterization at diagnosis using cfDNA in children with hematologic malignancies and certain solid tumors. The new method offers several advantages over existing detection methods, which include needing only a limited sample amount and demonstrating robust detection of a diverse set of genomic aberrations (154)Lei S, et al. (2025) Leukemia, 39: 420.. Similarly, for pediatric patients with advanced Wilms tumors, ctDNA profiling identified key chromosomal alterations and suggested potential prognostic value, with detectable ctDNA at diagnosis linked to poorer event-free survival (155)Madanat-Harjuoja LM, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 3047.. These findings highlight the value of ctDNA as a critical tool for both genetic characterization and risk assessment.

For CNS tumors, for which surgical access is limited, liquid biopsy of CSF is especially promising. In medulloblastoma, CSF ctDNA profiling accurately captured molecular characteristics of the tumor and detected MRD with greater sensitivity than standard methods, identifying relapse earlier than MRI in many cases (156)Escudero L, et al. (2020) Nat Commun, 11: 5376.(157)Liu APY, et al. (2021) Cancer Cell, 39: 1519.. Additionally, liquid biopsy in pediatric CNS tumors could help distinguish true progression from pseudo-progression—a phenomenon in which new lesions develop or a tumor first appears to grow based on therapy response but not because the cancer is progressing—and monitor molecular changes during therapy to guide treatment decisions without the need for repeated invasive procedures (158)Bonner ER, et al. (2018) NPJ Precis Oncol, 2: 29..

In solid tumors, liquid biopsy is enabling insights into tumor evolution and therapeutic resistance. In high-risk neuroblastoma, serial ctDNA profiling uncovered clinically actionable mutations, revealed resistance mechanisms in response to targeted therapy, and detected progression before standard imaging or biomarkers (159)Bosse KR, et al. (2022) Cancer Discov, 12: 2800.. A recent review of over 340 research studies investigating the utility of liquid biopsy in pediatric solid tumors emphasized that these benefits extend to multiple tumor types with applications across diagnosis, monitoring, and relapse detection (160)Janssen FW, et al. (2024) NPJ Precis Oncol, 8: 172..

Taken together, these studies underscore the versatility of liquid biopsy in pediatric oncology, with demonstrated potential for refining risk assessment, guiding therapy, and detecting relapse across cancer types. Beyond these applications, liquid biopsy holds promise for surveillance of children and adolescents with inherited CPSs, where it could help detect primary or secondary cancers at the earliest stages (see New Frontiers in Surveillance for Children With Cancer Predisposing Syndromes).

Yet routine clinical use of liquid biopsy remains limited in pediatric cancers compared to adult cancers, and a significant amount of research is still needed to improve assay sensitivity and standardize methods. Overcoming these hurdles will require continued investments in early detection, interception, and surveillance research to accelerate progress and ensure that the promise of liquid biopsy in pediatric cancer care matches advances already seen in adult oncology.

Shared Data and Collaborations Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research

Because pediatric cancers are rare and biologically distinct from adult cancers, progress depends on large-scale, interdisciplinary collaborations that facilitate sharing of patient samples, genomic data, research expertise, and clinical insights across institutions and around the globe. By sharing data and resources, these collaborations can accelerate our understanding of pediatric cancer biology and transform patient care. Building large-scale data resources that connect researchers worldwide, applying deep molecular profiling to personalize treatments for even the rarest tumor types, and harnessing cutting-edge technologies will drive the next generation of discoveries.

One of the most powerful strategies for advancing our knowledge of pediatric cancer biology has been the generation of shared data resources that give researchers and clinicians access to large, high-quality datasets linking genetic, clinical, and research information in ways that accelerate basic research discoveries and guide more personalized care.

For example, the Human Tumor Atlas Network (HTAN), launched as part of the Cancer Moonshot, is a collaborative, data-intensive research initiative supporting projects that apply advanced technologies to study individual cells and their molecular features within the structure of tumors. HTAN projects use single-cell and spatial multi-omic technologies (see Sidebar 5)—including transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and advanced imaging—to map the cellular and molecular architecture of tumors throughout the course of disease progression and treatment (161)de Bruijn I, et al. (2025) Nat Methods, 22: 664.. Shortly after its launch in 2018, the Center for Pediatric Tumor Cell Atlas was established as an HTAN center, which has developed foundational atlases of high-risk pediatric cancers, including high-grade glioma, neuroblastoma, and very high-risk ALL (121)Yu W, et al. (2025) Nat Genet, 57: 1142.(162)Sussman JH, et al. (2024) bioRxiv.. Another HTAN project is now leading the development of the Pediatric Solid Tumor Microenvironment Atlas, aimed at mapping the unique cellular and spatial features of the tumor microenvironment (see Tumor Microenvironment) in pediatric solid tumors, including rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, and Wilms tumor, to uncover mechanisms of acquired therapy resistance and identify targetable vulnerabilities.

Building and Connecting Data Networks

NCI initiatives are laying the foundation for precision medicine in childhood and adolescent cancers by creating integrated data and molecular characterization programs. For example, the NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (CCDI) aims to gather data from every child and AYA diagnosed with cancer and build a pediatric cancer data network that integrates genomic, clinical, imaging, and laboratory data. Under this initiative, the National Childhood Cancer Registry (NCCR) was launched in 2024. NCCR expanded upon the limited epidemiologic data (e.g., cancer incidence and survival data) previously available through the NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. By integrating epidemiologic, molecular, and clinical data, NCCR provides a more comprehensive resource than SEER for understanding cancer trends in children and AYAs. Developing platforms and tools to bring together research and clinical care data will improve treatment outcomes, quality of life, and survivorship for pediatric cancers.

The CCDI Molecular Characterization Initiative (MCI) was launched in collaboration with the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) (see Figure 1) to provide comprehensive clinical molecular characterization for children and AYAs with newly diagnosed solid tissue malignancies. MCI is leveraging molecular data from clinical assays of paired tumor and germline testing, which can distinguish inherited gene alterations from tumor-specific gene alterations. Furthermore, it can also identify fusion genes based on RNA as well as classify CNS cancer based on methylation. Additional efforts to produce research-based data from assays such as WGS, RNA sequencing, proteomics, and emerging technologies such as spatial transcriptomics, to inform clinical trials and tailor therapeutic treatment strategies, are planned or underway.

Data gathered from MCI is being integrated alongside existing genomic and clinical datasets from initiatives such as the NIH Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program (see Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research and Patient Care Through Evidence-Based Policies) for open-access sharing available to researchers and clinicians through the CCDI Data Ecosystem—a platform of tools and resources for storing, harmonizing, and sharing pediatric cancer data from separate repositories.

Other foundational resources include the Pediatric Cancer Data Commons, which harmonizes clinical datasets from disease-specific consortia and facilitates global data-sharing, and the St. Jude Cloud, which houses the largest publicly available pediatric cancer genomic dataset alongside an advanced suite of analysis tools. These platforms make rare tumor datasets accessible to a broad research community and provide critical clinical genomic data that could inform patient care. International efforts to harmonize data across national precision medicine programs are also ensuring that data can be shared broadly through internationally accessible data portals. For example, a joint initiative between Innovative Therapies for Children with Cancer and Hopp Children’s Cancer Center is working to create a platform for real-time federated archiving of data collected from international molecular tumor profiling platforms across seven countries (see Molecular Profiling Driving Precision Medicine).

Another example of how collaborative resources are advancing biological discovery is the Fusion Oncoproteins in Childhood Cancers (FusOnC2) Consortium. This initiative brought together experts in cancer biology, genomics, proteomics, chemistry, structural biology, and computational science to investigate fusion oncoproteins—molecular drivers that are a hallmark of many pediatric cancers (see Somatic Mutations). By pooling technologies, model systems, and expertise, FusOnC2 uncovered the mechanisms by which certain fusion proteins fuel tumor development.

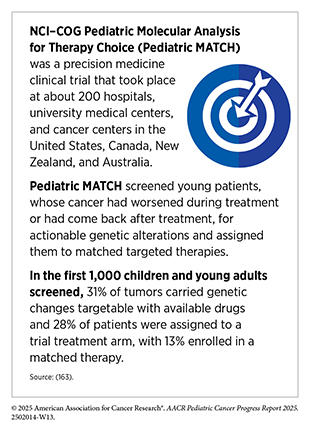

Integrating Molecular Insights Into Clinical Care

Comprehensive molecular profiling has become one of the most powerful tools for advancing precision medicine. When combined with large-scale collaborations, these approaches can reveal disease mechanisms, uncover new therapeutic targets, and match children and adolescents to precision therapies. For example, through MCI, comprehensive molecular testing for over 6,000 patients with newly diagnosed cancers resulted in a refined diagnosis for nearly 34 percent of patients, directly informed initial treatment with targeted therapy for 15 percent of patients, and facilitated clinical trial enrollment for 8.5 percent of patients (32)Flores-Toro J, et al. (2025) J Natl Cancer Inst..

The NCI Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) program is another effort demonstrating how molecular characterization can directly inform patient care. By applying comprehensive genomic analyses across childhood cancers, TARGET has identified key alterations driving diseases such as leukemias, neuroblastomas, Wilms tumor, and osteosarcomas (164)Ma X, et al. (2018) Nature, 555: 371.. For ALL, TARGET researchers defined the Philadelphia chromosome–like subtype, and uncovered that many of the patients harbored activated signaling, often driven by the BCR::ABL1 or other fusions involving key kinase proteins (see Somatic Mutations). Importantly, adding the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib to chemotherapy dramatically improved outcomes for these children without a need for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Collaborative, multi-institutional molecular profiling efforts are revealing the unique genetic drivers of childhood and adolescent cancers and creating the infrastructure to act on these insights to advance precision medicine in pediatric cancer care. Similar global initiatives are advancing precision medicine programs, expanding access to matched therapies, and establishing nationwide frameworks to bring precision medicine into routine pediatric cancer care (see Global State of Pediatric Cancer Clinical Trials).

Next Section: Pediatric Cancer Predisposition and Surveillance Previous Section: Pediatric Cancer Trends in the United States