- Global Epidemiology of Pediatric Cancers

- Global State of Pediatric Cancer Clinical Trials

- Molecular Profiling Driving Precision Medicine

- Multinational Platform Trials

- Challenges and Opportunities in Trials Globally

- Global State of Pediatric Cancer Treatment

- Global State of Pediatric Cancer Survivorship

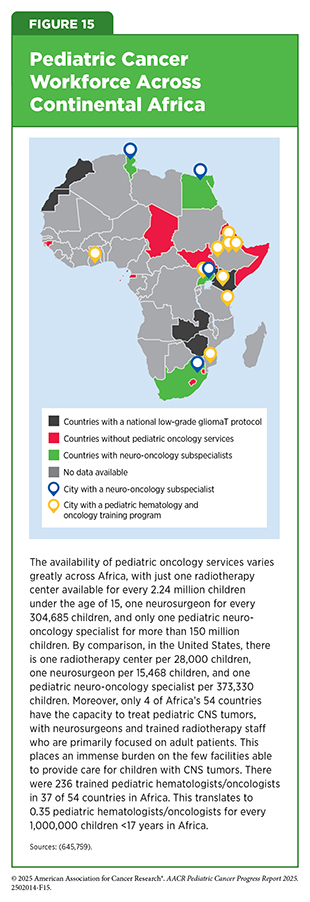

- Global State of the Pediatric Oncology Workforce

Understanding the Global Landscape of Pediatric Cancers

In this section, you will learn:

- Childhood cancer is a major global health challenge affecting hundreds of thousands of children annually. Global projections put the incidence of childhood cancers at close to 400,000 a year, with most cases and deaths occurring in low-income countries (LICs), lower middle-income countries (LMICs), and upper middle-income countries (UMICs), where survival remains far below that of high-income countries (HICs).

- Major inequities in access to timely and accurate diagnoses, essential medicines, treatments, supportive care, and trained health care providers across regions around the world result in children dying not because their disease is untreatable but because they do not have access to optimal clinical care.

- Precision medicine, molecular profiling, and multinational clinical trial platforms are expanding access to novel targeted therapies, though their benefits are concentrated in high-resource settings. International and regional collaborations between HICs and countries that are not high income are helping to strengthen health systems, improve trial participation, generate high-quality data, and broaden access to care.

- Sustainable progress against pediatric cancer depends on implementing solutions that are adapted to regional resources, strengthening local data systems and trial infrastructure, and ensuring that breakthroughs in treatment and supportive care reach every child worldwide.

- Pediatric cancer survivorship research remains disproportionately concentrated in HICs. Expanding research capacity in LICs, LMICs, and UMICs is essential to ensure that survivorship programs and care models reflect the realities and needs of children and families across diverse cultural and economic contexts.

- Addressing global workforce shortages through education, mentorship, and regional partnerships is key to ensuring that every child with cancer has access to skilled care providers, timely treatment, and quality survivorship care

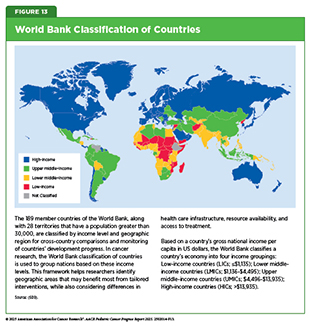

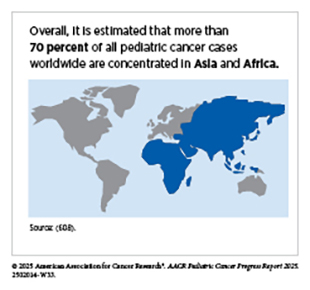

Pediatric cancer is a significant global health challenge, extending far beyond the United States (US) and other high-income countries (HICs), which together account for only an estimated 10 percent to 20 percent of the total pediatric cancer burden (66)Atun R, et al. (2020) Lancet Oncol, 21: e185.(602)Bhakta N, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: e42.. In contrast, between 80 percent and 90 percent of pediatric cancers occur in low-income and middle-income countries (see Figure 13) (602)Bhakta N, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: e42.(603)Noyd DH, et al. (2025) JCO Glob Oncol, 11: e2400274..

The absence of standardized, population-based cancer registries in many low-income and lower middle-income countries (LIC and LMIC, respectively) makes it difficult to capture the true burden of disease. A simulation study estimating the global burden of pediatric cancers in 2015 projected nearly 400,000 incident cancers in children 0 to 14 years, compared with only 224,000 cases diagnosed, a more than 40 percent difference (602)Bhakta N, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: e42.. Although these estimates of actual cases diagnosed align with those from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), an agency within the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) for similar time periods, health system barriers to access, referrals, and data collection contribute substantially to underdiagnosis (604)Ferlay J, et al. (2019) Int J Cancer, 144: 1941.(605)Ward ZJ, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: 483..

In addition, discrepancies in global cancer estimates from IARC and IHME arise from methodological differences, including the number of registries included (375 vs. 562, with 7 percent vs. 12 percent representing LICs and LMICs coverage, respectively) and the number of countries and territories analyzed (184 vs. 195, respectively) (605)Ward ZJ, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: 483.(606)International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Tomorrow. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Together, these challenges underscore the urgent need to strengthen global cancer surveillance, improve diagnostic capacity, and ensure that all children and adolescents, regardless of where they live, are counted and have access to timely, effective care.

In 2025, IARC estimated more than 280,000 new pediatric cancer cases and nearly 108,000 deaths worldwide (606)International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Tomorrow. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. However, as outlined above (i.e., differences in data collection methods, the number of registries included, underdiagnosis), these figures must be interpreted with caution, as they are likely underestimated by more than 40 percent and at least 5 percent, respectively (602)Bhakta N, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: e42.(605)Ward ZJ, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: 483.. Adjusting for these discrepancies suggests the true burden of pediatric cancers in 2025 may be closer to 470,000 new cases and 113,000 deaths. Despite the challenges in data collection and reporting, current estimates still provide important insight into the expected global burden of pediatric cancers.

Beyond the total burden, the types of cancers affecting children and adolescents worldwide mirror those seen in the United States. Globally, the most frequently diagnosed pediatric cancers are leukemias, central nervous system (CNS) tumors, and lymphomas (607)Wang M, et al. (2025) eClinicalMedicine, 89..

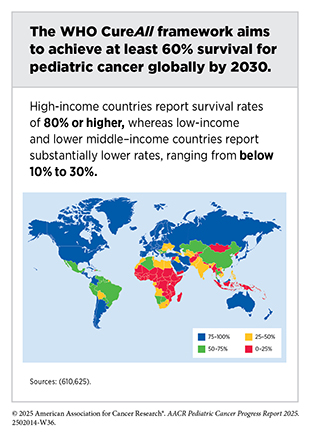

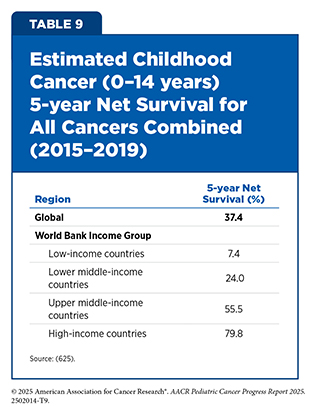

Global pediatric cancer patterns reveal substantial disparities in incidence and outcomes, largely influenced by differences in demographics, health care infrastructure, socioeconomic development, and timely access to diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care. For example, although treatment advances in the United States and other HICs have dramatically improved survival, these gains have not been realized uniformly around the globe. Although 5-year survival rates for pediatric cancers approach 80 percent in HICs, survival rates for these cancers in LICs and LMICs remain below 30 percent (610)World Health Organization. CureAll framework: WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer. Increasing Access, Advancing quality, Saving lives. Accessed: August 31, 2025..

Several system-level factors contribute to these disparities. In many low-resource settings, the availability of WHO’s essential medicines for childhood cancer as well as supportive care is limited (see Access to Clinical Care: Disparities and Solutions). A global survey of LICs and LMICs revealed that 60 percent of pediatric cancer patients had limited or no access to standard-of-care drugs needed to treat their disease (611)Seneviwickrama M, et al. (2025) BMC Cancer, 25: 181.. In addition, insufficient pediatric oncology infrastructure and workforce capacity often result in underdiagnosis, misdiagnosis, and delays in care. Retinoblastoma (RB)—a rare but aggressive eye tumor—offers a clear example of this disparity, whereby 30 percent to 40 percent of cases in developing countries are diagnosed at an advanced stage, compared to only 2 percent to 5 percent in developed countries (612)Chawla B, et al. (2017) Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs, 4: 187.. The lack of diagnostic infrastructure and trained personnel in LICs and LMICs leads to delayed diagnosis, resulting in more advanced disease at presentation and, consequently, markedly lower survival. As a result, survival rates for RB reach up to 98 percent in HICs but fall to just 57 percent in LICs (613)Wong ES, et al. (2022) Lancet Glob Health, 10: e380..

The economic burden on families is also profound. Bangladesh illustrates a challenge common to many LICs and LMICs. An estimated 9,000 pediatric cancer cases occur annually in Bangladesh; however, only about 5 percent of children receive care in a hospital setting (617)Rahman SA, et al. (2023) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 24: 69.. This gap is driven by limited infrastructure—only two cancer centers serve the entire country—as well as by the overwhelming out-of-pocket costs faced by families. In many LMICs, families spend more than their total monthly income on cancer treatment, often without financial assistance (e.g., subsidized health insurance) (614)Joseph AO, et al. (2021) Journal of Clinical Sciences, 18.(617)Rahman SA, et al. (2023) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 24: 69.. Even when treatment costs are subsidized, the additional expense of traveling long distances to access care results in another unaffordable burden on families (618)Pretorius L, et al. (2025).. These financial pressures not only limit access and delay the start of treatment but also increase the likelihood of treatment abandonment (see Access to Clinical Care: Disparities and Solutions) (619)Friedrich P, et al. (2016) PLoS One, 11: e0163090..

Treatment refusal and suboptimal quality of care further exacerbate disparities. For example, RB in LMICs is usually treated by enucleation—a surgical procedure that involves the removal of the eye from the socket (620)Dimaras H, et al. (2012) Lancet, 379: 1436.. However, the reatment is often refused due to lack of support for the visually impaired after the procedure, cultural beliefs in alternative treatments, and social stigma (621)Sitorus RS, et al. (2009) Ophthalmic Genet, 30: 31.(622)Chantada GL, et al. (2011) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 56: 341.(623)Olteanu C, et al. (2016) Ophthalmic Genet, 37: 137.(624)Counts LE, et al. (2025) JCO Glob Oncol, 11: e2400213..

Together, these factors highlight critical inequities in global health, wherein a child’s chance of surviving cancer is shaped less by biology, and more by geography, family income, and access to basic medicines.

Global Epidemiology of Pediatric Cancers

Epidemiologic studies provide important insights into the incidence, outcomes, and burden distribution of pediatric cancers across different regions of the globe.

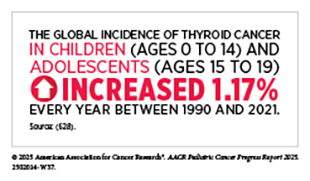

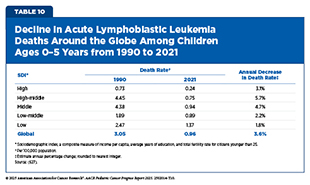

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric cancer and represents a major public health burden worldwide (626)Wu Y, et al. (2022) J Adv Res, 40: 233.. From 1990 to 2021, the incidence of pediatric ALL increased globally by nearly 60 percent, reaching 168,879 cases in 2021 (627)Ding F, et al. (2025) Front Pediatr, 13: 1542649.. Over the same period, however, deaths from ALL and the associated disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)—a measure of overall disease burden that combines years of life lost due to premature death and years lived with disability—declined by approximately two-thirds, reflecting significant progress in treatment and early detection (627)Ding F, et al. (2025) Front Pediatr, 13: 1542649..

However, these improvements were concentrated in regions with a high- and high-middle sociodemographic index (SDI)—a composite measure of income per capita, average years of education, and total fertility rate for citizens younger than 25—where access to health care infrastructure and diagnostic capacity have advanced markedly (627)Ding F, et al. (2025) Front Pediatr, 13: 1542649.. In contrast, low-SDI regions continue to face substantial barriers, with increasing ALL death rates and DALYs between 1990 and 2021 (627)Ding F, et al. (2025) Front Pediatr, 13: 1542649.. High-SDI regions, such as East Asia, achieved the greatest reductions in mortality and DALYs, while low-SDI regions, including sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean, continue to experience disproportionately high burdens of pediatric ALL. These disparities highlight the urgent need to strengthen health care infrastructure and improve resource allocation to support earlier detection and effective treatment and survivorship care of ALL in lower-SDI regions (627)Ding F, et al. (2025) Front Pediatr, 13: 1542649..

Many pediatric cancers remain asymptomatic in their early stages and can mimic common conditions such as malaria or tuberculosis, leading to delayed and often inaccurate diagnoses (610)World Health Organization. CureAll framework: WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer. Increasing Access, Advancing quality, Saving lives. Accessed: August 31, 2025.(629)Klootwijk L, et al. (2025) J Cancer Educ, 40: 54.(630)Moormann AM, et al. (2016) Current Opinion in Virology, 20: 78.. These delays stem from both patient- and health care provider–related factors. Cultural beliefs and stigma compound these challenges. For families, limited awareness of pediatric cancer, low health literacy, and reliance on traditional healers often postpone medical evaluation (629)Klootwijk L, et al. (2025) J Cancer Educ, 40: 54.(631)Njuguna F, et al. (2016) Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 33: 186.(632)Handayani K, et al. (2016) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 63: 2189.. For example, a study in Rwanda reported some pediatric patients were treated by traditional healers for up to 8 months before ultimately being diagnosed with leukemia in a health center (633)Rugwizangoga B, et al. (2022) Cancer Manag Res, 14: 1923.. In some cultures, there is no word for pediatric cancer, and families may avoid medical care due to fear, social stigma, or preference for alternative treatments (617)Rahman SA, et al. (2023) Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 24: 69.(623)Olteanu C, et al. (2016) Ophthalmic Genet, 37: 137.(634)Ahmed MM, et al. (2025) Sage Open Pediatrics, 12: 30502225251336861.(635)Afungchwi GM, et al. (2022) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 69: e29675.(636)Afungchwi GM, et al. (2017) BMC Complement Altern Med, 17: 209..

Health care providers frequently misdiagnose pediatric cancers due to limited training and minimal exposure to pediatric cancer cases (637)Lubega J, et al. (2021) Curr Opin Pediatr, 33: 33.. A study of 123 newly diagnosed Kenyan children with cancer noted that nearly 70 percent of participants were initially misdiagnosed and treated for malaria, infection, pain, or anemia (631)Njuguna F, et al. (2016) Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 33: 186.. When cancer is suspected, referral to specialized oncology centers is often difficult due to their scarcity and the long travel required, which many families with limited resources cannot manage (634)Ahmed MM, et al. (2025) Sage Open Pediatrics, 12: 30502225251336861..

Delays in diagnosis and referral to equipped health care facilities are particularly consequential for certain cancers. One pediatric cancer for which delayed diagnosis can have particularly severe consequences is RB, which is often first detected by the appearance of visible signs such as leukocoria (a white or gray reflection from the pupil of the eye) or strabismus (misaligned eyes that point in different directions).

A global cohort of 4,351 RB patients from 153 countries found nearly 85 percent of RB cases diagnosed in 2017 were from LICs and LMICs. The most common presenting sign was leukocoria (62.8 percent), followed by strabismus (10.2 percent) and proptosis (bulging of the eye; 7.4 percent). In patients living in HICs, RB was diagnosed earlier, with disease overwhelmingly confined to the eye and with very few cases of metastasis (638)Fabian ID, et al. (2020) JAMA Oncol, 6: 685.. By contrast, patients in LICs and LMICs presented later and had higher rates of metastasis and extraocular disease, which is disease that affects the muscles and tissues around the eye (638)Fabian ID, et al. (2020) JAMA Oncol, 6: 685..

Pediatric CNS tumors represent a significant global health concern, accounting for more than 20 percent of all pediatric cancers and serving as a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among children and adolescents (639)Williams LA, et al. (2021) Int J Epidemiol, 50: 116.. Over the past two decades, both incidence and mortality rates have been declining in HICs, and this decline is attributable to advances in early diagnosis and treatment for low-grade disease (640)Lu VM, et al. (2023) World Neurosurg, 179: e568.. Conversely, persistent challenges experienced in LICs and LMICs result in higher mortality and lower 5-year survival rates (641)Huangfu B, et al. (2025) Scientific Reports, 15: 17049..

Low-grade gliomas (LGG), which are often slow growing and under diagnosed because of their anatomic location and non-specific symptoms, account for 30 to 40 percent of pediatric CNS tumors, globally (642)Arnautovic A, et al. (2015) Childs Nerv Syst, 31: 1067.(643)van Heerden J, et al. (2023) Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, 40: 203.. Differences in data reporting, healthcare infrastructure, and access to high-quality, targeted treatment interventions affect the accuracy of the true burden of this disease, particularly in low-resource settings (644)Moreira DC, et al. (2023) JCO Glob Oncol, 9: e2300017..

A recent study, analyzing data between 2008 and 2018 across 15 pediatric oncology units in 6 African countries, illustrates this (645)van Heerden J, et al. (2025) Frontiers in Cancer Control and Society, Volume 3 – 2025.. More than half of pediatric patients with LGG did not undergo surgery, nearly 77 percent did not receive radiation, over 45 percent did not undergo chemotherapy, and only 3 percent had access to molecularly targeted therapy. Patients who received complete or partial resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy were mainly from pediatric oncology units in upper middle-income countries (UMICs). Despite these gaps, the overall 5-year survival rate for LGG across the study cohort exceeded 90 percent, reflecting the potential for cure when effective treatment is available. However, this figure largely represents outcomes from higher-resource centers, and must be interpreted with caution, as long-term follow-up was limited in LICs. Specifically, 5-year survival reached 100% in Tunisia, an LIC with comparatively greater resources but limited follow-up, and was nearly 90 percent in South Africa (UMIC), compared with just 67 percent in Uganda, a limited-resource LIC (645)van Heerden J, et al. (2025) Frontiers in Cancer Control and Society, Volume 3 – 2025.. These findings illustrate that while LGG can be highly curable, even in LICs, survival depends heavily on access to surgery and adjuvant therapies, which remain unevenly distributed across Africa (see Access to Clinical Care: Disparities and Solutions).

In addition, variations in SDI and political unrest—areas with armed conflict, tht is, use of force that results in at least 25 battle-related deaths per year in a specific country—contribute to the pronounced regional differences observed in pediatric cancer incidence, mortality, and survival. Together, these factors reveal that pediatric cancer is not only a medical challenge but also a reflection of broader social, economic, and political inequities that demand global attention.

The global burden of pediatric cancer highlights a profound inequity, where survival is determined less by biology than by geography and resources (see Table 9). Addressing these disparities requires urgent investment in pediatric oncology services, workforce training, and health system infrastructure, particularly in LICs and LMICs, if the WHO’s CureAll goal of at least 60 percent survival by 2030 is to be achieved.

Global Policies and Partnerships to Improve Care

Improving childhood cancer outcomes worldwide, particularly in LICs and LMICs where survival gaps are the greatest, relies on the global pediatric cancer research community (see Sidebar 21) to join forces in expanding access, promoting equity, and strengthening health care systems to improve care. In 2018, WHO, in partnership with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude), the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP), the patient advocacy and support organization Childhood Cancer International, and other global organizations, launched the Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer (GICC), with the goal of achieving at least 60 percent survival for children with cancer in all countries by 2030. The GICC works with governments to incorporate childhood cancer into broader cancer control and universal health coverage plans and to accelerate long-term policy and funding commitments. Since its launch, the initiative has engaged with over 80 countries, working to develop or strengthen national childhood cancer care strategies. Early efforts have focused on strengthening care systems for six cancers that together account for 50 percent to 60 percent of childhood cancers—ALL, Burkitt lymphoma, Wilms tumor, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, low-grade glioma, and RB (647)World Health Organization. WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer on the path to bridging the Survival Gap and attaining Universal Health Coverage: a 5-Year.

CureAll is the operational framework of the GICC that provides a structured approach to strengthening health care systems (610)World Health Organization. CureAll framework: WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer. Increasing Access, Advancing quality, Saving lives. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Its four pillars—centers of excellence, universal health coverage, standardized treatment regimens, and evaluation and monitoring—are supported by three enablers—advocacy, financing, and governance. Together, they guide countries in adapting evidence-based strategies to local contexts, ensuring that improvements in childhood cancer care are systematic, sustainable, and scalable.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), in collaboration with St. Jude and regional partners, has advanced the GICC using the CureAll framework. In 2021, regional working groups involving over 200 experts from 21 countries produced 14 regional resources, including technical guidelines, virtual training courses, parent/caregiver educational series, and awareness campaigns developed to address early detection, nursing, psychosocial support, nutrition, supportive care, treatment abandonment, and palliative care at the local level (649)Vasquez L, et al. (2023) Rev Panam Salud Publica, 47: e144.. As of 2023, these resources had already been widely disseminated and utilized across regions. For example, over 77,000 and nearly 9,000 participants enrolled in early diagnostic and palliative care courses, respectively, and technical documents, regional snapshots, and caregiver modules had more than 10,000 downloads. In addition, videos produced for an awareness campaign on childhood cancer symptoms and signs to improve early detection were viewed more than 11,000 times during the first month after its launch. This collaboration demonstrates the power of combining the CureAll framework with international and regional expertise, laying the groundwork for governments to integrate addressing childhood cancers into broader health agendas and to strengthen care across resource levels.

Global implementation networks, such as the St. Jude Global Alliance (St. Jude Global), also play an important role in addressing the needs of children with cancer. For example, St. Jude Global unites institutions and health care providers in more than 90 countries to create a network that focuses on improving access to quality pediatric cancer care and outcomes through strengthening workforce training and development of educational and clinical research infrastructures. For example, Targeting Childhood Cancer through the Global Initiative for Cancer Registry Development (ChildGICR) is a collaboration, established in 2020, between St. Jude Global and the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Through its educational programs, ChildGICR aims to address the unique challenges of childhood cancer by strengthening global cancer registration and improving high-quality population-data collection on cancer incidence and survival.

One such program was the ChildGICR Masterclass to improve capacity for population-based cancer registries on childhood cancer. This 12-week online program trained participants from 18 countries to create standard teaching materials for pediatric cancer registration, which have since been implemented in follow-up courses across 16 countries (650)Moreira DC, et al. (2024) JCO Glob Oncol, 10: e2300334.. The ChildGICR Masterclass can serve as a model for designing, planning, and implementing educational programs for health care professionals supporting better data collection for childhood cancer worldwide.

SIOP brings together more than 3,500 members from 130 countries, including oncologists, nurses, researchers, and patient advocates (651)International Society of Paediatric Oncology. About. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Through regional branches in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Europe, SIOP works to build pediatric oncology capacity by training health care providers, supporting regionally adapted treatment protocols, and advocating for pediatric oncology to be prioritized within national health plans. Its emphasis on creating sustainable, locally driven solutions ensures that progress is not dependent solely on external aid.

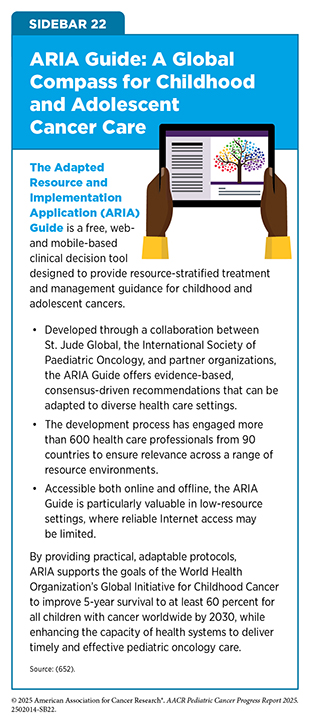

Developed through a partnership among St. Jude Global, SIOP, the International Society of Paediatric Surgical Oncology, the Paediatric Radiation Oncology Society, and other global organizations, the Adapted Resource and Implementation Application (ARIA) Guide provides consensus-driven, evidence-based treatment recommendations that can be adapted to local resource levels By offering context-specific guidance, ARIA empowers clinicians to deliver effective care despite systemic constraints (see Sidebar 22).

These partnerships exemplify what can be achieved when governments, health organizations, and regional groups work together, creating sustainable frameworks that strengthen health systems, expand access, and ultimately improve childhood cancer care. However, significant challenges remain, and continued commitment will be essential to ensure that every child, everywhere, has access to timely diagnosis and effective treatment.

Global State of Pediatric Cancer Clinical Trials

Nearly 90 percent of pediatric cancers occur in LICs, LMICs, and UMICs—yet only 28 percent of pediatric cancer clinical trials are conducted in these regions (653)World Health Organization. Research and development landscape for childhood cancer: a 2023 perspective. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Although advances in molecular profiling and adaptive clinical trial designs are reshaping childhood and adolescent cancer care, the benefits of these cutting-edge approaches have been felt primarily in HICs. Just 8.7 percent of pediatric clinical trials between 2010 and 2020 were international, and only 5.4 percent were intercontinental (654)de Rojas T, et al. (2021) Cancer Med, 10: 8462..

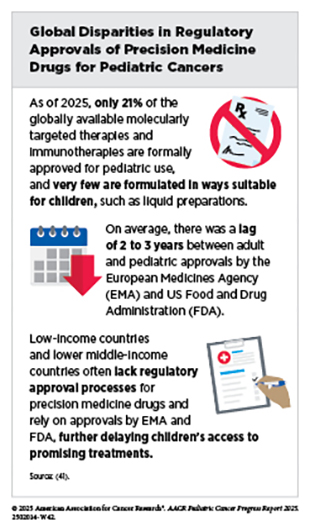

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have increasingly collaborated to align pediatric drug development requirements. These efforts aim to reduce duplication of studies, shorten drug development timelines, and provide consistency in evaluating safety and efficacy of treatments. For example, greater coordination of pediatric study plans has made it more feasible for sponsors to design global trials that include sites across both high- and low-resource regions, expanding access for patients while generating more robust data.

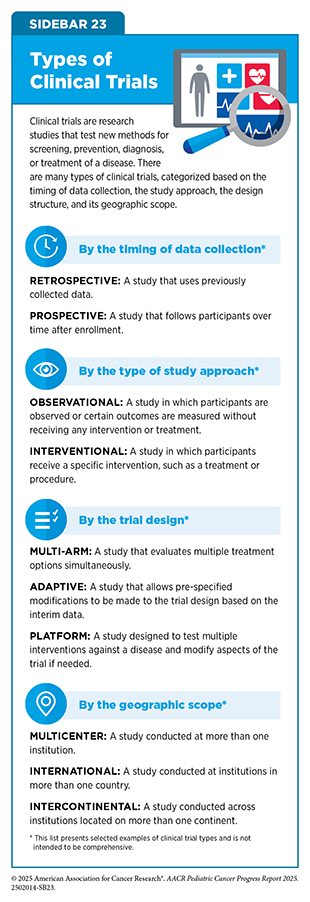

Clinical trials vary widely in their timing of data collection, study approach, design structure, and geographic scope—factors that influence where and how they are conducted (see Sidebar 23). A major milestone in streamlining regulations across regions came in December 2024 with the finalization of the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) E11A Pediatric Extrapolation Guideline (655)WIRB-Copernicus Group. The FDA Accepts ICH E11A on Pediatric Extrapolation: How Does This Impact Your Pediatric Study? Accessed: August 31, 2025.. This guidance builds on earlier frameworks by encouraging the use of existing data, whether from adult or pediatric populations, to inform study design for childhood cancers. By carefully applying lessons learned from one setting to another, regulators can reduce the need for unnecessary trials, focus research efforts where evidence gaps are greatest, and bring promising therapies to children with cancer quicker.

Molecular Profiling Driving Precision Medicine

Precision medicine programs aim to match a child or adolescent with cancer to the most effective therapy based on their cancer’s unique molecular features. By pairing molecular profiling with targeted treatments, precision medicine is reshaping pediatric cancer care across the globe, particularly in high-resource settings.

An observational study in the United Kingdom (UK) evaluated whether routine whole-genome sequencing (WGS) (see Sidebar 5) for all children with suspected cancer, not just for high-risk patients, could provide clinical benefit beyond standard of care molecular testing. The study found that across two childhood cancer centers, WGS reproduced all standard tests, modified treatment decisions in 7 percent of cases, and delivered additional diagnostic, risk, therapeutic, or germline genomic findings in 29 percent of cases (268)Hodder A, et al. (2024) Nat Med: s41591..

As our knowledge of how tumors evolve over the course of disease deepens, it is becoming clear that profiling a patient’s tumor repeatedly over time is as important as the initial profile. The Stratified Medicine Paediatrics program, the UK’s national precision medicine program for children and adolescents, offers clinical-grade sequencing to patients at the time of relapse or for treatment-refractory disease. In a retrospective study, tumor profiles at the time of diagnosis and at relapse were compared to understand how pediatric cancers evolve under therapy. The study found mutations that were only present at relapse, discovered patterns of relapse-associated mutations that were tumor type specific, and identified those common across cancer types. In addition, analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), collected from liquid biopsy in patients with solid tumors that have returned after treatment or continued to worsen despite therapy, demonstrated that this approach not only assesses genetic heterogeneity better than a single tissue biopsy in certain patients, but can also identify genomic and epigenomic drivers of pediatric cancer relapse and therapy resistance (see Liquid Biopsy) (419)George SL, et al. (2025) Cancer Discovery, 15: 717..

In the Netherlands, the individual Therapies (iTHER) program demonstrated the feasibility of using molecular profiling across the pediatric patient age groups and tumor types to inform diagnostic, prognostic, and targetable genetic alterations—including both somatic and germline cancer predisposing variants (see Genetic Alterations). In a prospective observational study, molecular profiling of tumors identified somatic alterations in 90 percent of patients, 82 percent of which were targetable, and germline cancer predisposing variants in 10 percent of patients. In addition, these findings helped refine diagnoses of 3.5 percent of patients and led to 13.9 percent of patients receiving molecularly matched treatments. This study demonstrates the feasibility of comprehensive molecular profiling in pediatric cancers, and as a result has made whole-exome sequencing (WES) and RNA sequencing, as well as DNA methylation profiling for CNS tumors and sarcoma, standard of care for all children and adolescents with cancer at a national pediatric center in the Netherlands (656)Langenberg KPS, et al. (2022) Eur J Cancer, 175: 311..

Australia’s Zero Childhood Cancer Program (ZERO) has similarly implemented a national multi-omic profiling framework advancing precision medicine for children with cancers. In an initial cohort of 247 high-risk pediatric patients, tumor and germline WGS and RNA sequencing identified targetable molecular alterations in over 70 percent of patients, and 5 percent of patients had changed diagnoses based on their tumor’s genomic profile. Among patients who were treated with therapies informed by molecular profiling, more than 30 percent experienced measurable clinical benefit (83)Wong M, et al. (2020) Nature Medicine, 26: 1742.. In an expanded cohort of 384 high-risk pediatric patients with more than 18 months of clinical follow-up data, where 43 percent of patients given a precision guided-treatment recommendation received that treatment, the 2-year progression-free survival was more than double that of patients receiving standard therapy and five times higher than that in patients receiving new or targeted therapies not guided by molecular findings (26 percent vs. 12 percent vs. 5.2 percent, respectively) (657)Lau LMS, et al. (2024) Nat Med, 30: 1913.. Importantly, children who received their recommended therapy early on in their treatment journey did significantly better than those who received it after their disease had progressed, with overall 2-year survival of greater than 50 percent among these children, all of whom had highest-risk cancers and a less than 30 percent likelihood of survival at enrollment.

Following the success of its national clinical trial focused on high-risk cancers, ZERO has expanded to include all children and adolescents (ages 0–18) diagnosed with cancer in Australia, regardless of cancer type or risk profile, enrolling more than 2,800 children and adolescents to date. In 2025, the Australian Government announced AUD 112.6 million investment over 3 years for ZERO, enabling it to continue delivering precision medicine for all children and adolescents, and to expand access to those ages 19 to 25 with pediatric-type cancers or relapsed childhood cancers. This pioneering nationwide effort can serve as a model for integrating precision medicine into routine pediatric cancer care worldwide.

Global collaboration and data-sharing are critical to advancing pediatric cancer research and care. Because pediatric cancers are both rare and highly diverse, breakthroughs in treatment are seldom achieved by any institution or country on its own. By connecting researchers, harmonizing data, and building shared platforms, international initiatives make it possible for discoveries in one part of the world to accelerate progress for all children and adolescents.

One example is the Pediatric Cancer Data Commons (PCDC) platform, which has worked with the international research community to standardize and federate, or link across institutions, oncology datasets for childhood cancers (659)Plana A, et al. (2021) JCO Clin Cancer Inform, 5: 1034.. By uniting clinical, genomic, and imaging data under shared governance and harmonized platforms, PCDC aims to remove barriers to research worldwide and provide more opportunities for developing treatments and improving outcomes for children. Likewise, the European Union (EU) has launched initiatives such as the UNCAN.eu platform, a federated data hub aiming to consolidate cancer research data and accelerate innovation, including for pediatric cancers (660)Boutros M, et al. (2024) Cancer Discov, 14: 30..

Data-sharing initiatives, such as the joint initiative between Innovative Therapies for Children with Cancer (ITCC) and Hopp Children’s Cancer Center (Hopp), are aiming to integrate pediatric precision medicine data across national programs. The ITCC Hopp initiative is working to create a platform for real-time federated archiving of data collected from international platforms for molecular tumor profiling around the globe, including Germany, France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Canada, Australia, and the UK.

For children and adolescents with recurrent or high-risk cancers, studies integrating multi-omic profiling can identify actionable alterations that enable matched therapies with clinical benefit in some cases. MAPPYACTS is one such international prospective trial of pediatric patients across France, Italy, Ireland, and Spain that aims at characterizing molecular features of recurrent or refractory cancers to suggest targeted therapies and referring patients into early-phase trials (e.g., AcSé-ESMART). The study identified at least one genetic alteration suggestive of a targeted therapy in 69 percent of patients. Of the patients with follow-up beyond 12 months, 30 percent received one or more matched targeted therapies; 56 percent of these treatments were in early clinical trials. Additionally, MAPPYACTS was the first study that used liquid biopsy and cfDNA analysis as a noninvasive approach to identify 76 percent of actionable genomic alterations in tumors of pediatric and young adult patients with non-CNS solid tumors (310)Berlanga P, et al. (2022) Cancer Discov, 12: 1266..

MSK-IMPACT is a specialized tumor-sequencing test used to detect large and small genetic alterations across more than 500 cancer-related genes. The Make-an-IMPACT program aimed to overcome financial and geographic barriers to molecular profiling by offering MSK-IMPACT testing at no cost to children and adolescents with rarer cancers across 11 countries. The program identified clinically relevant diagnostic or prognostic information in nearly 40 percent of pediatric patients with solid tumors including CNS cancers.

Targetable alterations were identified in 44 percent of solid tumors and 21 percent of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)–derived cfDNA samples. Serial CSF sampling also uncovered mutations that confer treatment resistance, underscoring the potential of cfDNA as a minimally invasive approach for monitoring disease (661)Farouk Sait S, et al. (2025) Clin Cancer Res, 31: 3285..

These studies highlight the feasibility of providing global access to advanced molecular profiling and its value in informing diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment for pediatric cancer worldwide.

Multinational Platform Trials

A persistent gap remains between drug approvals for adult and pediatric cancers. This gap stems from scientific challenges such as the rarity of pediatric cancers, regulatory complexities, and practical barriers including limited trial enrollment and scarce resources, all of which delay access of children and adolescents with cancer to promising new therapies that are often available to adults years earlier. In 2020, a cross-region analysis of approvals in the United States, the European Union, and Japan found that, compared to 103 targeted anticancer drugs labeled for adults, only 19 are approved for pediatric cancers, and just three have pediatric indications in all three regions (662)Nishiwaki S, et al. (2020) Sci Rep, 10: 17145.. Policies around the world are beginning to shift the drug development landscape for pediatric cancers by requiring and incentivizing the inclusion of children and adolescents in clinical studies. Continued progress will depend on the outcomes of innovative trials (see Sidebar 23), which are essential to demonstrate safety and efficacy of new therapies in pediatric populations.

In pediatric patients with advanced solid tumors, the expected response rate in traditional phase I trials is between 10 percent and 12 percent, whereas response rates in trials testing molecularly matched therapies have been shown to be 40 percent or higher (311)Geoerger B, et al. (2024) Eur J Cancer, 208: 114201.. AcSé-ESMART, a pan-Europe multi-arm adaptive interventional platform trial (see Sidebar 23), is using targeted treatment strategies to advance precision medicine for children, adolescents, and young adults (AYAs) with relapsed or refractory cancers. Since the AcSé-ESMART trial opened, over 250 patients have enrolled, and the trial has provided access to 13 new drugs or drug combinations, incorporating 16 adaptive arms for patients across six countries in Europe. Importantly, molecular profiling programs like MAPPYACTS (see Molecular Profiling Driving Precision Medicine) serve as a gateway to such trials. For example, 72 percent of patients who received matched treatment in a clinical trial after participating in MAPPYACTS did so within AcSé-ESMART, highlighting how profiling programs can facilitate therapeutic access for children and adolescents (311)Geoerger B, et al. (2024) Eur J Cancer, 208: 114201.(663)Geoerger B, et al. (2023) Nat Med, 29: 2985..

The United States–led international Pediatric Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (MATCH) trial has also tested the use of precision medicine for pediatric cancers. This trial took place at about 200 children’s hospitals, university medical centers, and cancer centers in the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Pediatric MATCH has proven to be a feasible, tumor-agnostic framework matching children and AYAs who have refractory cancers with molecularly targeted therapy trials (see Integrating Molecular Insights Into Clinical Care).

The Optimal Precision Therapies to CustoMISE Care in Childhood and Adolescent Cancer (OPTIMISE) trial is a multi-arm adaptive platform trial jointly led by Australia’s ZERO and Canada’s PRecision Oncology For Young peopLE (PROFYLE) initiative. This trial is a companion to the ZERO and PROFYLE precision oncology programs that will link patients to therapies based on their unique tumor profiles. OPTIMISE aims to evaluate molecularly targeted and immune-based therapies for children and adolescents with relapsed or refractory cancers and improve the outcomes for patients with advanced solid tumors, brain tumors, or lymphomas.

By bridging molecular findings with pediatric trial enrollment and aligning regulatory, industry, and academia partners around pediatric-focused drug development pathways, multinational platforms can accelerate the delivery of timely, evidence-based targeted treatments to the children and adolescents who need them.

Challenges and Opportunities in Trials Globally

Access to and enrollment in pediatric cancer clinical trials is uneven worldwide, influenced by barriers such as limited research infrastructure and staffing, inconsistent insurance coverage and financing, complex regulatory pathways, fragmented data systems, and practical barriers to accessing studies beyond national borders. While regions such as North America, Australia, and Europe have established strong clinical trial frameworks, many regions—including Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia—lack robust infrastructure or connections to global networks (664)Major A, et al. (2022) JCO Glob Oncol, 8: e2100266.. Improving childhood and adolescent cancer outcomes will require a deeper understanding of local stakeholders and resources necessary to establish effective clinical trial infrastructures, as well as increasing collaboration between international pediatric cancer clinical trial groups.

For example, collaborative clinical trial groups in pediatric oncology are unequally developed across Asia. The Asian Pediatric Hematology and Oncology Group (APHOG) was established to identify barriers and overcome hurdles in running collaborative clinical trials in Asia. Some of the key challenges the group reported included lack of insurance coverage, fragmented regulatory processes, limited data-sharing infrastructure, and a shortage of trained clinical trial staff (666)Li CK, et al. (2023) JCO Glob Oncol, 9: e2300153.. In response, organizations across Asia are working to expand clinical trial opportunities for pediatric patients with cancer. As one example, the Korean Society of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology in South Korea has initiated a number of multicenter clinical trials, including studies in ALL and acute myeloid leukemia (AML); however, challenges remain in performing nationwide studies—including limited workforce, resources, and institutional participation (666)Li CK, et al. (2023) JCO Glob Oncol, 9: e2300153.. APHOG recommended strengthening insurance frameworks to ensure that the cost of new treatments will be reimbursed and investing in expanding the health care workforce—including clinical investigators and nurses, data managers, and project coordinators—to support clinical trial operations.

In India, systemic, socioeconomic, and cultural barriers hinder early cancer diagnosis and sustained access to quality care, with many children presenting at advanced stages of disease. Regulatory bodies and regional initiatives are working to address these challenges. For example, the Indian Pediatric Oncology Group (InPOG) aims to accelerate the development of prospective multicenter clinical trials in the region, with the goal of improving the outcomes of childhood cancer in India through collaborative research. Since its launch in 2015, InPOG has initiated 31 studies—covering both observational (69.3 percent) and interventional (30.7 percent) trials—and has enrolled over 10,000 children across 114 institutions (667)Arora RS, et al. (2021) Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 5: 239.. While challenges remain, including limited financial resources and the need for dedicated infrastructure, efforts are underway to train clinicians and standardize research protocols to continue improving survival, quality of life, and treatment options for children across the country.

In Africa, the overall survival for childhood cancers is poor, ranging from 30.3 percent in North Africa to 8.1 percent in East Africa (668)van Heerden J, et al. (2020) JCO Glob Oncol, 6: 1264.. A systematic assessment of pediatric oncology clinical trials across 54 African countries found that only 12 percent of trials included children and adolescents, only 50 percent of pediatric trials were interventional, and sub-Saharan countries accounted for only 10.6 percent of pediatric trial activity. Additionally, 14 counties reported having no full-time pediatric oncologists and only two countries had pathology research capabilities, including WGS and molecular pathology for all diseases (668)van Heerden J, et al. (2020) JCO Glob Oncol, 6: 1264.. Africa-focused collaboratives and investments in improving access to diagnostic tools and health care infrastructure will be essential to respond to these challenges and improve outcomes for children in the continent.

Expanding access to pediatric cancer trials will require sustained global collaboration and innovative approaches to overcome regulatory and resource barriers. Leveraging collaborations between institutions in HICs and countries that are not high income can help transfer expertise, mentorship, and trial infrastructure. Additionally, sustained investment in training clinical personnel and strengthening data infrastructure will be pivotal to support these efforts and improve clinical trial participation, high-quality data generation, and equitable access to innovative therapies for children and adolescents everywhere.

Global State of Pediatric Cancer Treatment

Childhood cancer treatment has advanced dramatically over the past few decades. Once nearly fatal diseases, childhood cancers are increasingly treatable, with an overall 5-year net survival rate of nearly 80 percent in HICs (see Pediatric Cancer Trends in the United States) (625)Ward ZJ, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: 972.. Breakthroughs in childhood cancer treatment, once confined to HICs, are slowly making a tangible impact in countries that are not high-income or upper middle-income, although implementation and access remain substantially uneven within these countries as well as when compared to HICs (669)Gupta S, et al. Treating Childhood Cancer in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. In: Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, Horton S, editors. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3). Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank(670)Ehrlich BS, et al. (2023) Lancet Oncol, 24: 967.. Gains against childhood cancers in non-HICs thus far stem from cooperative clinical trials (see Access to Clinical Care: Disparities and Solutions), refinements in surgery and radiotherapy, safer chemotherapy regimens, and the systematic integration of supportive care that includes essential services, such as infection control, nutrition, and pain relief (see Sidebar 24).

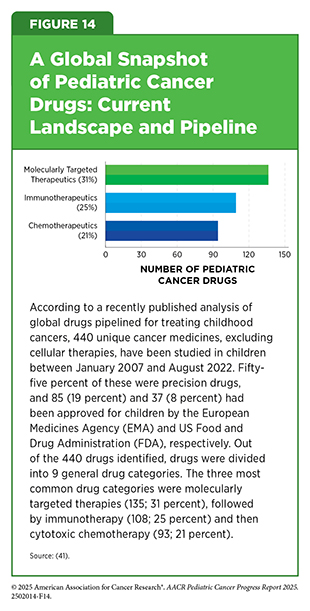

Around the globe, treatment options for children with cancer have expanded well beyond conventional chemotherapy in recent decades, although uneven access remains a major challenge (see Access to Clinical Care: Disparities and Solutions). In a recent study, researchers conducted a large-scale review of more than 5,000 clinical trials registered worldwide between 2007 and 2022, focusing on medicines tested in children with cancer. The analysis showed that there are 440 unique cancer medicines under study, excluding cell therapies (41)Cleveland C, et al. (2025) Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 9: 544.. Furthermore, targeted therapies and immunotherapies made up more than half of all medicines tested in children (55 percent), reflecting a shift from traditional chemotherapy (see Figure 14) (41)Cleveland C, et al. (2025) Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 9: 544..

Pediatric oncology has pioneered risk-stratified therapy, which tailors treatment intensity according to a child’s prognosis and helps reduce overtreatment in low-risk cases while escalating treatment in high-risk ones (673)DelRocco NJ, et al. (2024) Leukemia, 38: 720.. These improvements mean more children not only survive cancer but do so with fewer permanent side effects.

Pediatric ALL as a Model of Global Progress

A few decades ago, an ALL diagnosis was considered fatal for most children around the globe (see Table 10). In the 1960s, survival rates in HICs were below 10 percent, while in many LICs and LMICs, children with ALL had little chance of cure well into the 1990s (669)Gupta S, et al. Treating Childhood Cancer in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. In: Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R, Horton S, editors. Cancer: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 3). Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank(674)Pui CH, et al. (2006) N Engl J Med, 354: 166.. Today, thanks to decades of research, 5-year survival for children with ALL exceeds 90 percent in most HICs, but survival remains much lower in non-HICs, where resources and access to therapies are limited (675)Kantarjian H, et al. (2025) Lancet, 406: 950.(676)Hayashi H, et al. (2024) Cancers (Basel), 16..

The first major shift in treatment and management of pediatric ALL occurred in HICs, when risk-stratified therapy based on clinical and biological features such as age, white cell count, and cytogenetic markers, became routine. This approach, developed in the 1980s and 1990s, allowed lower-risk children to avoid overly harsh treatment and higher-risk children to receive more aggressive, targeted regimens. The result was a safer, smarter way of curing leukemia that steadily increased survival and quality of life (676)Hayashi H, et al. (2024) Cancers (Basel), 16..

With advances and innovations in understanding the genetic underpinnings of the disease, molecular classification of ALL became more precise (677)Tran TH, et al. (2022) Semin Cancer Biol, 84: 144.(678)Pui CH, et al. (2019) Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 16: 227.. Discoveries such as the Philadelphia chromosome—a genetic mutation that leads to the formation of the oncogenic BCR::ABL fusion gene—enabled targeted therapies like tyrosine kinase inhibitors to be combined with chemotherapy, dramatically improving outcomes for children with ALL carrying the Philadelphia chromosome (679)Lejman M, et al. (2021) Int J Mol Sci, 22.. Genomic profiling also guided more personalized approaches, reducing toxicity while improving survival (680)Kim H, et al. (2025) Blood Res, 60: 40.. These scientific advances created a template for precision medicine in childhood cancer (677)Tran TH, et al. (2022) Semin Cancer Biol, 84: 144.(681)Ray A, et al. (2024) Children (Basel), 11..

Countries like Brazil, India, and South Africa adapted these advances by tailoring HIC protocols to their regional needs. Simplifying risk stratification, enhancing regional drug supply, and modifying supportive care strategies helped increase survival rates to 60 percent to 80 percent in some centers (see Global State of Pediatric Cancer Survivorship).

India provides a striking example of how locally adapted approaches can improve childhood cancer survival. Indian pediatric oncology centers adopting modern risk-stratified protocols have reported survival rates approaching 70 percent, demonstrating sustained progress from decades of local adaptation. In a recent study involving nearly 2,700 patients ages 1 to 18 at centers across India, the Indian Childhood Collaborative Leukaemia (ICiCLe) group used genetic testing and minimal residual disease (MRD) to categorize B-cell ALL into standard, intermediate, and high-risk groups to deliver progressively intensified therapy (682)Gogoi MP, et al. (2025) Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia, 37: 100593.. Children identified as standard risk and treated with lower-intensity regimens had better survival than high-risk patients who required more intensive therapy (disease-free and overall survival of 61 percent and 73 percent, respectively) (682)Gogoi MP, et al. (2025) Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia, 37: 100593.. This is the first collaborative clinical study in children with ALL in India using genetic testing and MRD risk stratification to decrease the intensity of treatment in standard-risk ALL and streamlining treatment across all participating pediatric oncology centers (683)Das N, et al. (2022) Trials, 23: 102.. Through cooperative protocol adherence, risk stratification, data collection, and approaches to overcome regulatory hurdles, the ICiCLe group demonstrates that even with fewer resources, these strategies can yield survival outcomes approaching those in HICs (682)Gogoi MP, et al. (2025) Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia, 37: 100593.(683)Das N, et al. (2022) Trials, 23: 102..

In Latin America, the Pediatric Oncology Latin America (POLA) network launched resource-adapted ALL protocols in 2018. By addressing challenges, such as controlling infections and obtaining drugs, POLA rapidly improved access to care and ALL survival across multiple centers (684)Duffy C, et al. (2023) Front Oncol, 13: 1254233.. South American centers have also documented major gains against pediatric ALL. An analysis across multiple countries in Latin American showed 5-year overall survival improvements for pediatric ALL ranging from 52 percent in low-resource areas to more than 86 percent where standardized protocols were implemented with adequate supportive care (684)Duffy C, et al. (2023) Front Oncol, 13: 1254233.. The wide survival gap in pediatric ALL is in part explained by the findings of a recent survey of Latin American countries, which indicated that countries with the highest human development index (HDI)—a composite measure of health, education, and income—generally showed dramatic advances in survivorship, access to treatment, and availability of national pediatric cancer control programs (685)Cappellano A, et al. (2024) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 71: e30973..

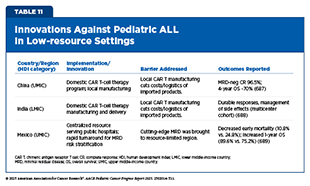

Researchers across the globe are continually working to implement regionally tailored strategies that are helping to further close the gaps in survival outcomes for pediatric ALL between HICs and LMICs (see Table 11). Despite challenges, pediatric ALL has become a model of progress against childhood cancers, with survival gains that are no longer confined to HIC nations but are increasingly, albeit unevenly, achievable across diverse settings (686)Duffy C, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 2247..

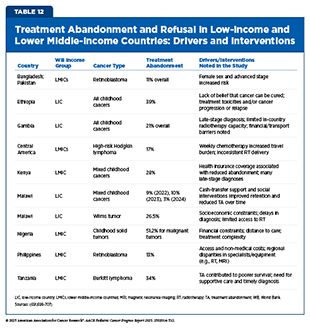

Still, persistent challenges remain. Many non-HICs continue to struggle with late diagnosis, limited laboratory infrastructure, and high treatment abandonment rates (see Table 12) (690)Ahmad I, et al. (2023) JCO Glob Oncol, 9: e2200288.(691)Molla YM, et al. (2025) Sci Rep, 15: 10534.. Without reliable access to essential medicines, even the best protocols cannot succeed. Moving forward, success depends on building stronger health systems and improving access to diagnostics and affordable chemotherapy drugs.

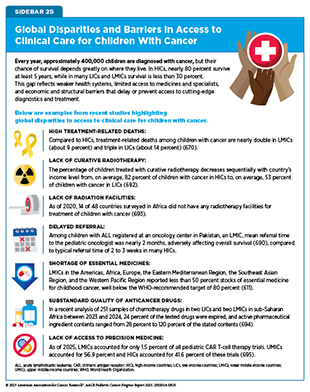

Access to Clinical Care: Disparities and Solutions

Over the past decade, advances in pediatric oncology have transformed survival for many children in HICs. At the same time, the gap between HICs and non-HICs in access to cutting-edge therapies has widened; the reasons for this disparity are multifactorial reasons and include the failure of advances made in HICs to reach countries that are not high income and the inequality of health systems and resources in non-HICs. Children in LMICs and LICs often face delayed diagnoses; shortages of trained specialists; limited access to chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation; and challenges such as malnutrition, treatment complications, and families abandoning care due to cost (see Global State of Pediatric Cancer Survivorship, Sidebar 25, and Table 12) (637)Lubega J, et al. (2021) Curr Opin Pediatr, 33: 33..

The inequities in cancer outcomes illustrate one of the most urgent global health challenges—children dying not because their disease is untreatable, but because effective therapies fail to reach them. The most impactful progress against pediatric cancers will not necessarily be the most cutting-edge treatments, but rather access to care that is affordable, scalable, and sensitive to the realities of health care systems worldwide. Recognizing this challenge, WHO and St. Jude launched the Global Platform for Access to Childhood Cancer Medicines (Global Platform) in 2021 with $200 million in funding from St. Jude to provide uninterrupted access to essential medicines to 120,000 children with cancer in up to 30 to 40 LICs and LMICs within the next 5 to 7 years. Supported by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and PAHO for procurement and distribution, the Global Platform aims to address long-standing weaknesses in fragmented medicine markets that often leave LICs and LMICs vulnerable to supply shortages, high costs, and substandard or falsified drugs.

In February 2025, the first medicines were delivered to countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, providing an example of how a unified system can ensure safe, affordable access to childhood cancer medicines (696)Burki T (2025) Lancet Oncol, 26: e130.(697)Downing JR, et al. (2025) Lancet Oncol, 26: 540.. In September 2025, as a part of the Global Platform, health officials in Ghana announced a program that will provide free essential medicines to children from low-income families beginning in early 2026 through nine treatment centers nationwide. Through this program, developed in partnership with the St. Jude Global Platform, Ghanaian government officials hope to narrow the survival gaps for children with cancer, in line with the CureAll framework (698)Adepoju P (2025) Lancet Oncol..

Global cooperation can help address formulation and dosing challenges that remain significant barriers to equitable access. Child-friendly liquid formulations or dispersible tablets, for example, are often unavailable in low-resource settings, making safe administration for younger children difficult (708)Otsokolhich M, et al. (2024) EJC Paediatric Oncology, 3: 100163.. Coordinated regulatory action and public–private partnerships will be critical to accelerating the development and distribution of appropriate formulations worldwide.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is one of the most significant breakthroughs in pediatric oncology (see Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment). In children with ALL, this treatment can induce deep, durable remissions where other therapies fail. Early trials demonstrated the dramatic efficacy of the treatment in pediatric ALL and showed how transformative this could be for young patients, but access remained clustered in HICs (709)Burki TK (2021) Lancet Haematol, 8: e252.. In 2025, large follow-up studies confirmed that CAR T-cell therapy is a lifesaving therapy for children, yet LICs and LMICs remain almost entirely excluded because of the cost of production, infrastructure demands, and reimbursement barriers (710)Martinez-Gamboa DA, et al. (2025) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 209: 104648.. Although some CAR T-cell therapies can be produced from T cells that have been frozen and shipped across borders, others require fresh cells and local manufacturing facilities and expertise, limiting availability by geography (711)Kim SJ, et al. (2024) Ann Lab Med, 44: 210.(712)Bucklein V, et al. (2023) Hemasphere, 7: e907..

Additional barriers—including high costs, limited clinical infrastructure, and shortages of trained personnel—further restrict access to these lifesaving therapies for pediatric patients in many regions. However, researchers are beginning to find innovative solutions to address these barriers. In India, the CAR T-cell therapy NexCAR19 is being manufactured at roughly one-tenth the cost of comparable commercial therapies, with early-stage clinical trials showing encouraging safety and efficacy profiles (713)Mallapaty S (2024) Nature, 627: 709.. This achievement demonstrates the potential of regionally developed, lower-cost CAR T-cell therapies to expand access in LMICs and bridge the gap in delivering transformative treatments worldwide.

Research has shown that the success of treatment depends on accurate diagnosis and risk stratification. MRD testing has rapidly become a cornerstone of modern leukemia care, but such capacity is rare in many LIC and LMIC settings. A recent study from Mexico demonstrated the impact of bringing standardized MRD diagnostics into public hospitals. By centralizing testing in a reference laboratory and ensuring timely turnaround, researchers showed that early mortality dropped from nearly 1 in 4 to just over 1 in 10. One-year overall survival improved from 75 percent to almost 90 percent (714)Reiterova M, et al. (2025) Clin Chem Lab Med, 63: 1419.. This is a clear example of how diagnostic innovation can close survival gaps when thoughtfully implemented in constrained settings.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has also expanded dramatically over the past decade, enabling precision approaches that can guide targeted therapy decisions. Consortia such as INFORM (Individualized Therapy For Relapsed Malignancies in Childhood) in Europe, ZERO in Australia, and PG4KDS (Pharmacogenetics for Kids) in the United States have shown that genomic profiling identifies actionable findings in a majority of pediatric cancers (see Global State of Pediatric Cancer Treatment). Yet, uptake of matched therapies remains low in many places, largely because LIC and LMIC health systems lack the infrastructure, trained workforce, and financial resources to support NGS integration in routine care for children (715)Radich JP, et al. (2022) Annu Rev Pathol, 17: 387..

Researchers are taking innovative, locally developed and resourced approaches to overcome some of these challenges. As one example, in India, resource-adapted molecular profiling—using fluorescently labeled probes to visualize genetic changes and antibody-based assays to detect protein expression and localization within tumor cells—has been used for pediatric CNS tumors, including medulloblastomas and gliomas. These low-cost imaging methods can substitute for advanced platforms when methylation profiling or next-generation sequencing is not feasible and have improved diagnostic precision and risk-based treatment planning in resource-limited settings (716)Kaur K, et al. (2019) J Neurooncol, 143: 393.(717)Rao S, et al. (2024) Brain Tumor Pathol, 41: 109..

Several molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapies have become standard in HICs but remain out of reach elsewhere. Dinutuximab, an anti-GD2 antibody, improves survival for children with high-risk neuroblastoma and is a standard component of therapy in HICs. However, access is constrained in LICs and LMICs by cost and procurement challenges, limiting its uptake despite strong evidence of benefit (718)Jain R, et al. (2021) Pediatr Hematol Oncol, 38: 291.(719)Shen AL, et al. (2023) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 70: e30680.(720)Denburg AE, et al. (2022) JCO Glob Oncol, 8: e2200034.. Similarly, brentuximab vedotin combined with chemotherapy improves event-free survival for children with Hodgkin lymphoma, yet adoption has been variable (see New Hope for Patients With Lymphoma). Even in health systems that recognize its value, high cost remains a barrier to widespread use (355)Castellino SM, et al. (2022) N Engl J Med, 387: 1649.(721)Xie S, et al. (2024) Health Econ Rev, 14: 38.(722)Sathyanarayanan V, et al. (2020) JCO Glob Oncol, 6: 1124..

The same story holds true for NTRK inhibitors, which are highly effective molecularly targeted therapies for rare pediatric CNS tumors driven by NTRK fusions and represent a new frontier. But global access to these therapeutics remains a barrier, with high drug cost limiting their use and leaving children in most countries without a potentially lifesaving option (723)Moreira DC, et al. (2024) CNS Drugs, 38: 841.. Researchers are working to mitigate some of these issues. For example, a new study GLOBOTRK, launched with a partnership between academia and industry, is recruiting children with brain tumors from the US as well as from several LMICs, including Egypt, India, Jordan, Brazil, and Peru. The study, a phase II trial, aims to give entrectinib as a first treatment to young children with brain cancers whose tumors have the NTRK or ROS1 fusions. Importantly, entrectinib is formulated to be administered orally, which makes it ideal to help treat children in low-resource settings, where access to dedicated infusion centers is not always possible (724)ClinicalTrials.gov. Study Details | NCT06528691 | Entrectinib as a Single Agent in Upfront Therapy for Children. Accessed: October 17, 2025..

Another source of disparities in access to precision medicine drugs is the lack of rigorous drug approval processes in LICs and LMICs, which largely rely on approvals by EMA and FDA, further delaying access to cutting-edge treatment for children with cancer (41)Cleveland C, et al. (2025) Lancet Child Adolesc Health, 9: 544.(725)Aristizabal P, et al. (2021) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 41: e315..

Radiotherapy, or radiation therapy, remains an essential part of treatment for many childhood cancers, yet it is one of the most unevenly distributed resources globally, including in HICs (726)Mohan R (2022) Precis Radiat Oncol, 6: 164.. Expert panels have issued guidance about how to deliver safe and effective radiotherapy for children in resource-limited settings (727)Parkes J, et al. (2017) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 64 Suppl 5.. The guidance emphasizes adapting treatment protocols, ensuring basic quality assurance, and prioritizing training as essential steps in settings where sophisticated equipment and staffing are lacking (727)Parkes J, et al. (2017) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 64 Suppl 5.. Furthermore, the Rays of Hope initiative of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) aims to improve access to and quality of radiation therapy in LMICs through training the workforce and procuring equipment, among other approaches (728)International Atomic Energy Agency. Rays of Hope. Accessed: Oct 17, 2025.. In a partnership with St. Jude’s, the initiative also focuses on delivering technical resources, curricula and guidance documents for radiation oncologists, radiotherapy technicians and medical physicists, and supporting their implementation in selected LMICs (729)International Atomic Energy Agency. IAEA and St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Partner to Bridge Gap in Global Childhood Cancer Care | International Atomic Energy Agency. Accessed: Oct 17, 2025.. Even in HICs, advanced radiotherapy approaches, such as proton therapy, are unequally distributed. Children with cancer face additional, disproportionate barriers to accessing cutting-edge radiotherapy, with geography and socioeconomic status strongly influencing whether children with cancer can benefit from proton therapy (726)Mohan R (2022) Precis Radiat Oncol, 6: 164.. These disparities underscore that access challenges not only are an issue in countries that are not high income but also persist within HICs.

Beyond access to specific drugs, treatment types, and technologies, broader socioeconomic factors continue to drive survival differences. Multiple studies have shown that outcomes for several pediatric cancers are directly correlated

with HDI: The higher the HDI, better the outcomes (see Global Epidemiology of Pediatric Cancers) (730)Cui Y, et al. (2024) J Glob Health, 14: 04045.(731)Li X, et al. (2025) Front Public Health, 13: 1513526.. At the same time, examples from Latin America and Asia show that strategies tailored to regional needs can make a real difference. The challenge now is to scale these models globally. Ensuring access to diagnostics such as MRD and NGS would allow clinicians everywhere to tailor therapy. Developing strategies for purchasing immunotherapies and targeted drugs in bulk and pricing them for different countries based on income level could reduce cost barriers. Expanding radiotherapy infrastructure, including adapted protocols for non-HICs, would address one of the longest-standing inequities in access to these treatments. And creating international frameworks to accelerate pediatric approvals could shorten the lag that leaves children waiting years for therapies already available to adults. Without deliberate efforts to extend access to the full continuum of care, from diagnosis and supportive care to advanced therapeutics, these survival gaps will persist.

Partnerships between institutions in HICs and non-HICs have demonstrated that sustainable pediatric cancer care programs can also be built even in resource-limited settings. In Latin America, a partnership between St. Jude, Guatemalan medical, political, and community leaders, and the Guatemalan government Ministry of Health and Social Welfare enabled the establishment of the National Pediatric Cancer Unit, which provides cancer care to all Guatemalan children regardless of ability to pay. As a result, treatment abandonment dropped from 42 percent to less than 1 percent and survival rates more than doubled (732)Ribeiro RC, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 53.. In Brazil, collaboration between St. Jude, a local grassroots advocacy group, and a regional hospital resulted in increased training and education of health care providers and implementation of adjusted ALL treatment protocols, increasing 5-year survival in pediatric ALL from 25 percent to 63 percent (732)Ribeiro RC, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 53..

Across Africa, regional collaboration has been equally transformative. Through strengthening workforce development and regionally adapted treatment protocols, efforts led by the Franco-African Pediatric Oncology Group have improved the outcomes of Burkitt lymphoma from 50 percent to 60 percent (668)van Heerden J, et al. (2020) JCO Glob Oncol, 6: 1264.. Similarly, the Collaborative Wilms Tumour Africa Project was established to improve Wilms tumor outcomes by implementing consensus-adapted treatment protocols–developed by the SIOP Committee for Paediatric Oncology in Developing Countries–across eight centers in sub-Saharan Africa. Protocol adaptation led to improved survival without evidence of disease from 52 percent to 69 percent, reduced treatment abandonment from 23 percent to 12 percent, and decreased treatment-related deaths from 21 percent to 13 percent. The Collaborative Wilms Tumour Africa Project is now just one initiative under the Collaborative African Network of Clinical Care and Research for Childhood Cancer network, which also includes the Supportive Care for Children With Cancer in Africa initiative to improve supportive care and the Toward Zero Percent Abandonment initiative to eliminating treatment abandonment (733)Chitsike I, et al. (2020) JCO Glob Oncol, 6: 1076..

Taken together, the global landscape of pediatric cancer reveals both remarkable progress and stark inequities. Advances in diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care have transformed outcomes for many children in HICs, yet survival remains unacceptably low in parts of the world where most cases occur. Sustained progress will depend on closing these gaps by expanding access to essential medicines and technologies, strengthening health systems and clinical trial capacity, and ensuring that breakthroughs in precision medicine and supportive care reach every child, everywhere.

Global State of Pediatric Cancer Survivorship

Globally, survival after a childhood cancer diagnosis remains marked by profound inequities. The 5-year net survival for childhood cancer is estimated at 37 percent for 2015 to 2019, with wide variation between regions (625)Ward ZJ, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: 972.. In recognition of this disparity, the WHO GICC aims to increase pediatric cancer survival rates to 60 percent worldwide by 2030 (see Global Policies and Partnerships to Improve Care). Achieving this goal requires not only access to timely diagnosis and curative therapy but also increased attention to supportive and survivorship care.

In HICs, advances in supportive care, such as infection prevention, transfusion support, and symptom management, have been central to survival gains, making intensive treatments more tolerable (734)Lehrnbecher T, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 1774.(735)Nellis ME, et al. (2019) Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, 33: 903.(736)Kruimer DM, et al. (2024) Support Care Cancer, 32: 766.(737)Walker R, et al. (2024) Support Care Cancer, 32: 747.. Efforts to safeguard long-term quality of life, such as fertility preservation, have also expanded (484)Yang EH, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 344.(738)Lo AC, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2351062.. However, both access to these services and research evaluating their impact remain largely confined to HICs, leaving children in less developed countries with few supportive care options and little evidence to guide survivorship care.

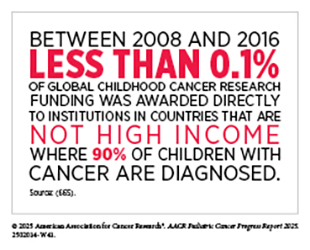

Within the framework of the WHO GICC and the CureAll approach, survivorship care in non-HICs remains a critical area in need of immediate attention. Despite this need, investment in pediatric cancer survivorship research remains inadequate. Between 2008 and 2016, only 11.6 percent of the $2 billion invested globally in childhood cancer research supported survivorship studies (including research into patient care and pain management, supportive and end-of-life care, quality of health care delivery, and long-term side-effects of cancer treatment), while the majority of funds enabled research into pediatric cancer biology and drug development (665)Loucaides EM, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: e672.. Even more concerning, only 5.5 percent of global pediatric cancer research funding supported health care delivery, an area essential for establishing sustainable survivorship programs, underscoring the lack of investment in interventions to improve long-term outcomes in resource-limited settings. This chronic underfunding has left major gaps in knowledge about childhood cancer survivorship in non-HICs.

A recent assessment of the global landscape of childhood cancer survivorship research from 1980 to 2021 found that 95 percent of pediatric cancer survivorship research originated from HICs, with a disproportionately large proportion of studies originating from the United States (739)Martos M, et al. (2025) JAMA Oncol.. By contrast, only 5 percent of survivorship studies were conducted in UMICs and LMICs, and no survivorship studies emerged from LICs. Moreover, when survivorship research is conducted in UMICs and/or LMICs, it is almost exclusively limited to physical late effects, with little attention to mental health, psychosocial challenges, or health promotion (739)Martos M, et al. (2025) JAMA Oncol.(740)Signorelli C, et al. (2024) JCO Glob Oncol, 10: e2300418.. Studies conducted in low-resource settings also tend to be smaller and limited to single institutions, reducing generalizability. This imbalance raises concerns that existing survivorship guidelines and models of care are poorly aligned with the realities of survivors in resource-limited settings.

While comprehensive long-term follow-up guidelines developed in North America and Europe provide valuable frameworks for survivorship care, they are based on treatment exposures and resources specific to high-income settings. However, children in non-HICs often receive modified treatment regimens that alter their risk for late effects (603)Noyd DH, et al. (2025) JCO Glob Oncol, 11: e2400274.. For example, in some LICs and LMICs, regional treatment guidelines that omit radiotherapy and lower anthracycline doses have been implemented in response to limited resources and constrained health infrastructure (670)Ehrlich BS, et al. (2023) Lancet Oncol, 24: 967.(741)Lemmen J, et al. (2023) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 185: 103981.. By contrast, in HICs, irradiation and anthracycline exposure have been consistently identified as risk factors for second primary cancers, cardiotoxicity, infertility, endocrine disorders, and other late effects (21)Bhatia S, et al. (2023) Jama, 330: 1175.. The less intensive regimens used in some non-HICs may therefore alter both the prevalence and spectrum of late effects. As such, long-term follow-up guidelines must be adapted to reflect local treatment patterns and health system capacities.

Although knowledge of physical late effects has expanded considerably, research addressing mental health, psychosocial well-being, and health promotion in pediatric cancer survivorship remains limited (740)Signorelli C, et al. (2024) JCO Glob Oncol, 10: e2300418.. The lack of focus on these areas is especially concerning for patients in non-HICs, where stigma surrounding mental health, shortages of trained mental health professionals, and the high cost of services limit access to psychosocial care (740)Signorelli C, et al. (2024) JCO Glob Oncol, 10: e2300418.(742)Vaishnav M, et al. (2023) Indian J Psychiatry, 65: 995.(743)Sapag JC, et al. (2018) Glob Public Health, 13: 1468.(744)Alemu WG, et al. (2023) BMC Psychiatry, 23: 480.. As a result, many children and families in non-HICs remain without the support needed to address anxiety, depression, fear of recurrence, and the broader social challenges that persist long after treatment ends.