Supporting Survivors of Pediatric Cancers

In this section, you will learn:

- As of 2022 (the most recent year for which data are available), more than 521,000 pediatric cancer survivors were living in the United States (US), and this number is projected to exceed 580,000 by 2040.

- Thanks to advances in treatment, the 5-year relative survival rate for US children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer now exceeds 85 percent for all cancers combined.

- Pediatric cancer survivors face a multitude of long-term physical, psychosocial, and financial challenges because of their cancer and treatment.

- Evidence-based frameworks for survivorship care, including the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines, are essential to monitoring, preventing, and managing late effects across the lifespan.

- Parents and caregivers of children with cancer often experience significant psychological and financial strain, highlighting the need for comprehensive, family-centered support throughout the cancer journey.

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), a person is considered a cancer survivor from the time of cancer diagnosis through the balance of the person’s life (457)Mollica MA, et al. (2025) Cancer, 131: e70039.(458)National Cancer Institute. Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Statistics and Graphs. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Pediatric cancer survivors include individuals of any age who were diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 0 and 19.

As of 2022, which is the most recent year for which such data are available, more than 521,000 pediatric cancer survivors were living in the United States (US), and this number is projected to grow to over 580,000 by 2040 (459)Ehrhardt MJ, et al. (2023) Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 20: 678.. In addition, an estimated 9,550 US children (ages 0 to 14 years) and 5,140 adolescents (ages 15 to 19 years) are expected to be diagnosed with cancer in 2025 (460)Wagle NS, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin..

Thanks to remarkable advances in treatment, children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer today are living longer and healthier lives. Among US children, the 5-year relative survival rate for all cancers combined has improved from just 58 percent in the mid-1970s to more than 85 percent for those diagnosed between 2015 and 2021 (see Pediatric Cancer Trends in the United States). Similar progress has been observed among US adolescents, whose 5-year relative survival rate increased from 68 percent in the mid-1970s to 88 percent between 2015 and 2021 (5)NCI Childhood Cancer Data Initiative. NCI NCCR Explorer. Accessed: June 15, 2025.(16)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10..

As more children and adolescents survive cancer and reach adulthood, it is increasingly important to understand their unique survivorship experiences. Therapies used to treat cancer can damage organs, tissues, or bones, putting survivors at risk of adverse health outcomes known as late effects. These late effects include physical, neurocognitive, psychosocial, and financial problems that can emerge months or years after diagnosis or treatment. Because children with cancer are treated while their bodies are still growing and developing, they are particularly susceptible to late effects and therefore require long-term follow-up care to monitor and manage these late effects.

A cancer diagnosis in childhood or adolescence also deeply affects families, caregivers, and peers, who often serve as the primary support network. The emotional, financial, and logistical burdens on these individuals can be profound and long-lasting. Therefore, research, services, and care strategies must extend beyond survivors to include their broader support system.

The following sections underscore the challenges faced by pediatric cancer survivors and their families, highlight advances in pediatric cancer survivorship, and present evidence-based approaches to delivering effective, age-appropriate survivorship care.

Challenges Faced by Pediatric Cancer Survivors

While advances in pediatric oncology have markedly improved survival rates, pediatric cancer survivors remain at risk for long-term physical, psychosocial, and financial difficulties resulting from the cancer itself or the therapies used to treat

it. The type and severity of these late effects depend on several factors, including the cancer type and stage at diagnosis, the specific type of treatment and doses received, as well as the survivor’s age and overall health at the time of treatment. These long-term challenges can adversely affect survivors’ quality of life and place additional emotional and financial strain on families and caregivers. Although research is ongoing, a greater understanding of these challenges and strategies to address them is essential to better support this vulnerable population.

Physical Challenges

Pediatric cancer survivors are at risk for a broad spectrum of short- and long-term health effects resulting from their disease and its treatments. Short-term effects, which typically arise during therapy or shortly thereafter, may include hair loss, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, pain, and changes in appetite or taste. Some survivors of pediatric cancer, such as Martin Townsend, continue to experience lasting effects—for example, fatigue and low energy—long after completing therapy. As survival rates improve and many children live decades beyond their initial diagnosis, the burden of long-term and late effects has become a central focus of survivorship care. Late effects can involve multiple organ systems and include heart and lung problems, impaired growth and development, endocrine and reproductive disorders, neurocognitive impairments, reduced sex hormone production (hypogonadism), bone damage (osteonecrosis), and second primary cancers (see Table 6).

Endocrine Disorders

Endocrine dysfunction refers to problems with the body’s hormone system, which regulates essential functions such as growth, sexual development, reproduction, sleep, hunger, and metabolism. Endocrine dysfunction is a common late

effect of pediatric cancer treatment, affecting up to 50 percent of childhood cancer survivors (461)Mostoufi-Moab S, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 3240.. The risk of endocrine dysfunction varies depending on factors, such as age at treatment, sex, tumor location, and the type and intensity of therapy received. For example, radiation to the brain can impair growth hormone production, leading to short stature and/or delayed puberty; radiation to the neck can result in thyroid disease; and pelvic radiation or certain chemotherapy drugs can affect fertility (i.e., the ability to conceive children) (462)Rose SR, et al. (2016) Nat Rev Endocrinol, 12: 319.(463)Chemaitilly W, et al. (2017) Eur J Endocrinol, 176: R183.. Endocrine-related dysfunction can also lead to obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and impaired bone health, all of which may contribute to long-term cardiovascular and skeletal complications (461)Mostoufi-Moab S, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 3240.(462)Rose SR, et al. (2016) Nat Rev Endocrinol, 12: 319.(463)Chemaitilly W, et al. (2017) Eur J Endocrinol, 176: R183.(464)Chemaitilly W, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 2153.. Many endocrine-related late effects can be effectively managed with appropriate medical care, underscoring the importance of lifelong, risk-based follow-up care.

Cardiotoxicity

Cardiotoxicity, or heart damage, is a common late effect of childhood cancer therapy. Certain cancer treatments can damage the heart and blood vessels, leading to long-term heart problems such as cardiomyopathy (weakening of the heart muscle), coronary artery disease (narrowing of the heart’s blood vessels), congestive heart failure, arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythms), and pericardial disease (inflammation around the heart). Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of non–cancer-related mortality in pediatric cancer survivors, who have a four-fold increased risk of CVD-related mortality compared with the general population (465)Dixon SB, et al. (2023) Lancet, 401: 1447.(466)Bhandari R, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol: JCO2500385..

A substantial proportion of cardiovascular conditions are attributable to prior exposure to anthracycline chemotherapeutics—a type of antibiotics that damage the DNA in cancer cells—and/or irradiation as part of childhood cancer treatment (see Less Is Sometimes More). Numerous studies have demonstrated a clear dose–response relationship, whereby higher cumulative doses of anthracyclines or radiotherapy are associated with a proportionally greater risk of subsequent heart problems, particularly cardiomyopathy (467)Ehrhardt MJ, et al. (2023) Lancet Oncol, 24: e108.(468)Mulrooney DA, et al. (2016) Ann Intern Med, 164: 93.(469)Haddy N, et al. (2016) Circulation, 133: 31.. In the case of radiotherapy, cardiotoxicity risk is determined not only by the total radiation dose, but also by the volume of cardiac tissue exposed to radiation (470)Bates JE, et al. (2019) J Clin Oncol, 37: 1090..

Because cardiovascular complications may develop decades after treatment and often without early warning signs, experts recommend lifelong cardiac monitoring for anyone exposed to anthracyclines or radiation near the heart. Regular follow-up care, heart imaging, and reducing other heart disease risk factors—such as smoking, high blood pressure, or obesity—can help detect problems early and improve long-term health.

Second Primary Cancers

Second primary cancers (SPCs) are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among survivors of pediatric cancers (465)Dixon SB, et al. (2023) Lancet, 401: 1447.(471)Suh E, et al. (2020) Lancet Oncol, 21: 421.. Unlike recurrence of the original cancer, SPCs represent a new, biologically distinct cancer that can emerge months or years after the original cancer was diagnosed and treated. Research shows that people who survive childhood cancer are two to six times more likely to develop SPC in their lifetime compared to the general population (466)Bhandari R, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol: JCO2500385.(472)Turcotte LM, et al. (2019) J Clin Oncol, 37: 3310.(473)Turcotte LM, et al. (2015) J Clin Oncol, 33: 3568.(474)Teepen JC, et al. (2017) J Clin Oncol, 35: 2288.. The most common SPCs in this population include breast cancer, thyroid cancer, central nervous system (CNS) tumors (notably meningiomas and gliomas), soft-tissue sarcomas, and certain skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma (21)Bhatia S, et al. (2023) Jama, 330: 1175.(474)Teepen JC, et al. (2017) J Clin Oncol, 35: 2288.(475)Wang Z, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 2078.(476)Roganovic J (2025) World J Clin Cases, 13: 98000..

Among pediatric cancer survivors, the development of SPCs is primarily attributable to prior treatment exposures. Radiation therapy is a well-established, dose-dependent SPC risk factor, especially for tumors that arise in or near areas of the body directly exposed to the radiation (21)Bhatia S, et al. (2023) Jama, 330: 1175.(474)Teepen JC, et al. (2017) J Clin Oncol, 35: 2288.(477)Turcotte LM, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 2145.. For example, radiation to the neck increases the risk of developing thyroid cancer, while radiation to the abdomen and pelvis increases the risk of colorectal cancer (21)Bhatia S, et al. (2023) Jama, 330: 1175.. Additionally, certain chemotherapy agents (e.g., alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and platinum-based compounds) have been associated with increased risk of SPCs, including breast cancer, sarcoma, and certain blood cancers (459)Ehrhardt MJ, et al. (2023) Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 20: 678.(472)Turcotte LM, et al. (2019) J Clin Oncol, 37: 3310.(474)Teepen JC, et al. (2017) J Clin Oncol, 35: 2288.(478)Ghosh T, et al. (2024) Cancer Med, 13: e70086..

The reduced use and lower dosing of radiotherapy in recent decades have led to meaningful declines in the SPC incidence (15)Armstrong GT, et al. (2016) N Engl J Med, 374: 833.(22)Yeh JM, et al. (2020) JAMA Oncol, 6: 350.(474)Teepen JC, et al. (2017) J Clin Oncol, 35: 2288.. Despite these improvements, the absolute lifetime risk of SPCs among pediatric cancer survivors remains elevated compared to the general population, underscoring the need for lifelong, risk-based follow-up care to support early detection and improve long-term outcomes. Although treatment-related exposures have long been recognized as the primary drivers of SPC risk in childhood cancer survivors, emerging evidence suggests that inherited genetic factors also play a significant role and are an area of active study.

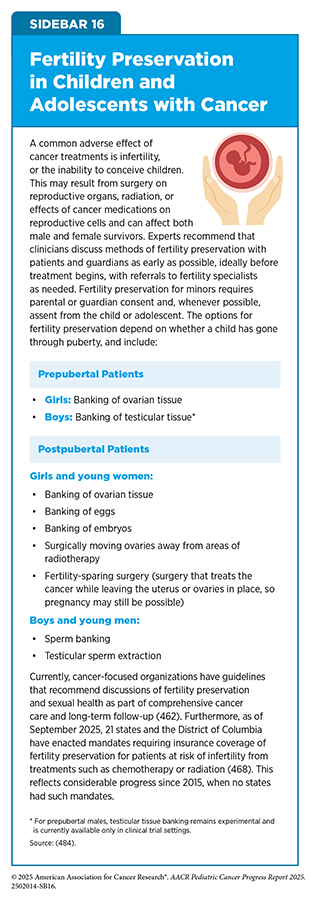

Reproductive Health and Fertility

Survivors of pediatric cancers often face lasting reproductive health challenges as a result of their treatment. Certain therapies, including alkylating chemotherapy agents and radiation to the pelvis or abdomen can damage the ovaries or testes (479)Chow EJ, et al. (2016) Lancet Oncol, 17: 567.(480)van Dorp W, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 2169.. This damage may occur during treatment or may develop years afterward, leading to early menopause or premature ovarian failure in women, and reduced or absent sperm production in men (481)Su HI, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol, 43: 1488..

Female survivors are less likely to achieve pregnancy compared with peers or siblings without a history of cancer. Those who become pregnant have an increased risk of complications, such as preterm birth and low birth weight, especially after pelvic radiation (482)van Dijk M, et al. (2020) J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 146: 1451.(483)Zgardau A, et al. (2022) J Natl Cancer Inst, 114: 553.. Male survivors are similarly less likely to father children, particularly after treatment with high-dose alkylating agents or radiation affecting the testes (479)Chow EJ, et al. (2016) Lancet Oncol, 17: 567..

Because cancer treatment can affect fertility, parents/guardians of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer should talk with their child’s health care providers about whether infertility is a risk and, if so, which fertility preservation options may be appropriate (see Sidebar 16) (481)Su HI, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol, 43: 1488.. Experts recommend discussing fertility and sexual health at the time of cancer diagnosis, before starting therapy, and revisiting these topics during follow-up care (481)Su HI, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol, 43: 1488.(484)Yang EH, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 344.. However, many survivors report receiving inadequate information about the potential reproductive or sexual health effects of cancer treatment. In a recent study of pediatric and young adult cancer survivors, nearly 70 percent expressed concerns about their sexual health and function, and 36 percent reported concerns about fertility. However, only about half of these survivors reported having received any communication from a health care professional about sexual health issues and reproductive concerns (485)Gerstl B, et al. (2024) J Cancer Surviv, 18: 1201..

Integrating fertility preservation programs into cancer care may help address these gaps. A recent study found that implementing a multidisciplinary program at a large pediatric cancer center resulted in nearly all eligible patients receiving fertility counseling or consultation and increased use of fertility preservation methods (486)Corona LE, et al. (2025) J Pediatr Surg, 60: 162400..

Neurocognitive Impairment

An estimated one-third of pediatric cancer survivors experience long-term neurocognitive impairments attributable to their cancer and its treatment (19)Phillips SM, et al. (2015) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 24: 653.(488)Phillips NS, et al. (2021) J Clin Oncol, 39: 1752.

(489)Jacola LM, et al. (2021) J Clin Oncol, 39: 1696.. Frequently observed impairments include deficits in attention, processing speed, memory, learning, planning, and organizational skills, often accompanied by difficulties with regulation of emotions. These impairments are strongly associated with adverse educational, social, and occupational outcomes in adulthood (490)Gummersall T, et al. (2020) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 145: 102838.. For example, in a large study of more than 1,500 survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), survivors demonstrated higher rates of inattention, hyperactivity, learning problems, and were more likely to require special education services than siblings without a cancer history (491)Jacola LM, et al. (2016) Lancet Psychiatry, 3: 965.(492)Zheng DJ, et al. (2018) Cancer, 124: 3220.. Survivors with neurocognitive deficits are less likely to complete higher levels of education, and are more likely to be unemployed, compared to survivors without such difficulties (68)Hernádfoi MV, et al. (2024) JAMA Pediatr, 178: 548.(493)Prasad PK, et al. (2015) J Clin Oncol, 33: 2545.(494)Papini C, et al. (2025) Neuro Oncol, 27: 254..

Importantly, for pediatric cancer survivors, neurocognitive impairment is not limited to the early post-treatment years. Longitudinal studies show that survivors who initially exhibit no cognitive deficits can develop cognitive problems decades after treatment (495)Phillips NS, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2316077.. These late-onset impairments are associated with prior treatment exposures (e.g., cranial radiation therapy and high-dose alkylating agents), chronic health conditions, as well as potentially modifiable risk factors including smoking and physical inactivity. Collectively, these findings underscore the need for lifelong, risk-adapted neurocognitive surveillance and timely interventions, beginning during treatment and extending well into adulthood (21)Bhatia S, et al. (2023) Jama, 330: 1175..

Accelerated Aging and Chronic Health Conditions

Survivors of pediatric cancers are also at an increased risk of developing chronic, age-related health conditions earlier in life (see Sidebar 17). These include CVD, stroke, and SPCs. Reports indicate that 60 percent to more than 90 percent of childhood survivors develop one or more chronic health conditions following their cancer diagnosis (19)Phillips SM, et al. (2015) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 24: 653.(20)Bhakta N, et al. (2017) Lancet, 390: 2569.. By age 50, adult survivors of childhood cancer have an average of 17 chronic health conditions—which is nearly double the burden of disease, compared to the general population at that age (20)Bhakta N, et al. (2017) Lancet, 390: 2569..

Research measuring biological age has shown that pediatric cancer survivors age about 5 percent faster per year and can appear up to 16 years older biologically than their cancer-free peers, with faster aging linked to increased risk of premature mortality (497)Guida JL, et al. (2024) Nat Cancer, 5: 731.. Other studies report that by age 30, many survivors have health profiles similar to healthy individuals in their 60s (498)Williams AM, et al. (2023) J Natl Cancer Inst, 115: 200..

This earlier onset and higher frequency of chronic conditions in survivors is often referred to as accelerated aging. Among survivors, accelerated aging arises, in part, from damage caused by cancer treatments, such as radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation. These therapies can harm DNA, shorten telomeres (the ends of chromosomes), alter epigenetic patterns, and trigger chronic inflammation, all of which speed up the deterioration of organs and tissues (499)Bhatia R, et al. (2022) Curr Oncol Rep, 24: 1401..

Treatment-related injuries activate many of the same biological pathways that underlie normal aging, reducing organ reserve (e.g., the capacity of an organ to perform functions beyond baseline daily needs) and increasing vulnerability to chronic diseases. However, the mechanisms behind accelerated aging are likely multifactorial and remain partially understood. Accelerated aging can be quantified using clinical tools, such as cumulative burden scores that summarize the total impact of chronic health conditions, as well as molecular measures like DNA methylation–based “epigenetic clocks,” which may help identify survivors most in need of early interventions (497)Guida JL, et al. (2024) Nat Cancer, 5: 731.(500)Esbenshade AJ, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 3629.(501)Wang Z, et al. (2025) Nat Rev Cancer, 25: 129..

Because survivors are at risk for developing age-associated diseases decades earlier than the general population, lifelong, risk-adapted follow-up care is essential. This includes earlier and more frequent screening for conditions such as CVD and SPCs, along with preventive strategies aimed at slowing biological aging.

Late Effects of Precision Medicine

In recent years, improved understanding of the biology of pediatric cancers has led to the development of novel therapies that promise more effective and less toxic treatment. However, these new therapies are not without risk for late effects. Molecularly targeted treatments, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, have been associated with growth impairment, thyroid dysfunction (most commonly hypothyroidism), and other endocrine abnormalities that may persist long after therapy completion (505)Samis J, et al. (2016) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 63: 1332.(506)Hijiya N, et al. (2021) Blood Adv, 5: 2925.(507)Millot F, et al. (2014) Eur J Cancer, 50: 3206.. Other targeted agents, such as vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, have been linked to cardiovascular complications, such as hypertension and/or blood clots, however the long-term cardiac effects for pediatric survivors remain incompletely understood (508)Versmissen J, et al. (2019) Cardiovasc Res, 115: 904.(509)Chow EJ, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 2231..

Certain immunotherapies, including rituximab, have been linked to prolonged immune complications. Among the most notable are B-cell aplasia, a depletion of antibody-producing white blood cells, and hypogammaglobulinemia, an immune system disorder that heightens the risk of recurrent infections (403)Minard-Colin V, et al. (2020) N Engl J Med, 382: 2207.(510)Labrosse R, et al. (2021) J Allergy Clin Immunol, 148: 523.. The late effects of other novel therapies, including biologic agents and antibody-based immune therapies, remain poorly understood in the pediatric population, underscoring the importance of continued research.

Psychosocial Challenges

A cancer diagnosis during childhood or adolescence coincides with stages of rapid development of essential psychological, cognitive, and social skills. Children with cancer often face disruptions in their psychosocial development as a result of their diagnosis, treatment, and subsequent late effects. In the short term, these challenges may manifest as emotional distress, adjustment difficulties, maladaptive coping, reduced social engagement with peers, missed educational and employment opportunities, and financial toxicity.

The emotional toll of a cancer diagnosis during childhood can be profound. In fact, survivors of pediatric cancers are more likely to have symptoms of anxiety and depression compared to siblings and the general public (511)Brinkman TM, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 3417.(512)Marchak JG, et al. (2022) Lancet Oncol, 23: e184.(513)Brinkman TM, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 2190.. This population is also more susceptible to major psychiatric conditions, including autism, attention-deficit disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder, with the greatest number of mental health illnesses experienced by survivors of brain cancers and blood cancers (514)Hsu TW, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 2054..

Fear of cancer recurrence is also common among pediatric cancer survivors. According to a recent study, approximately one-third of adult survivors of childhood cancer reported heightened fear that their cancer might return or that they could develop SPCs. These fears were strongly associated with elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression (515)Pizzo A, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2436144.. Mental health challenges in this population also extend to suicidal ideation, or thoughts of suicide. Reports indicate that approximately 10 percent of childhood cancer survivors report experiencing suicidal ideation, particularly during active treatment. While childhood cancer survivors are more likely to report suicidal ideation, their risk of suicide death is comparable to that of the general population (516)Tan JY, et al. (2025) JAMA Netw Open, 8: e2457544..

The psychological burden of pediatric cancer often extends into daily life, influencing coping strategies and risky health behaviors. When compared to healthy siblings, young adult survivors of childhood cancers reported increased loneliness that subsequently increased anxiety, depression, and the likelihood of smoking. Long-term follow-up with these patients found higher levels of suicidal ideation, as well as heavy/risky alcohol consumption (517)Papini C, et al. (2023) Cancer, 129: 1117..

Survivors of pediatric cancers also face unique social and educational challenges, including difficulties with peer relationships, academic performance, and establishing independence from parents and caregivers (see Sidebar 18). Compared to their siblings, survivors are more likely to experience social withdrawal and antisocial behaviors, which can hinder healthy social development (492)Zheng DJ, et al. (2018) Cancer, 124: 3220.(518)Schulte F, et al. (2018) Cancer, 124: 3596.. According to a recent analysis, individuals diagnosed with CNS tumors in early childhood experienced slower development of academic readiness skills, particularly in reading and math, which was associated with poorer academic outcomes later in life (519)Somekh MR, et al. (2024) J Natl Cancer Inst, 116: 1952.. These challenges often persist into adulthood, as survivors are less likely to complete higher levels of education, live independently, or marry and have children compared to those without a cancer history (68)Hernádfoi MV, et al. (2024) JAMA Pediatr, 178: 548.(491)Jacola LM, et al. (2016) Lancet Psychiatry, 3: 965.(520)Vuotto SC, et al. (2024) Ann Clin Transl Neurol, 11: 291..

Financial Challenges

The economic burden of a cancer diagnosis and treatment, known as financial toxicity, is a significant challenge for survivors of pediatric cancer and their families, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Evidence from large cohort studies demonstrates that adult survivors of childhood cancer are more likely than siblings or peers to report many forms of financial hardship, including material (e.g., difficulty paying bills or medical expenses), psychological (e.g., worry or distress about finances), and behavioral (e.g., delaying or forgoing medical care due to cost) (525)Nipp RD, et al. (2017) J Clin Oncol, 35: 3474.. In one study, nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of adult survivors of childhood cancer reported some type of financial hardship, including being reported to debt collection, facing problems paying medical bills, and worrying about paying rent or affording nutritious food (526)Nathan PC, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 1000..

Financial hardship in this population is also associated with difficulties in acquiring health insurance, life insurance, and planning for retirement. These financial challenges can have profound effects on survivors’ mental health and quality of life. For example, survivors experiencing financial hardship are more likely to report anxiety, depression, and lower quality of life compared to those without financial hardship (527)Huang IC, et al. (2019) J Natl Cancer Inst, 111: 189..

Many survivors face long-term health issues and functional limitations that affect their ability to work, leading to employment instability and health-related unemployment (68)Hernádfoi MV, et al. (2024) JAMA Pediatr, 178: 548.. Long-term studies show that a substantial proportion of survivors who initially achieved full-time employment later transitioned to part-time work or unemployment over time (528)Bhatt NS, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2410731.. Pediatric cancer survivors are less likely than peers without a cancer history to graduate from college, a disadvantage that often translates into lower-paying jobs, reduced lifetime earning potential, and an increased risk of financial toxicity (68)Hernádfoi MV, et al. (2024) JAMA Pediatr, 178: 548.(529)Saatci D, et al. (2020) Arch Dis Child, 105: 339.(530)Guy GP, Jr., et al. (2016) Pediatrics, 138: S15..

The combination of elevated health care needs, reduced earning potential, and persistent financial hardship among pediatric cancer survivors underscores the critical importance of access to affordable, comprehensive health insurance coverage for this population. Survivors who lack stable employment or who face gaps in employer-sponsored insurance are particularly vulnerable to being uninsured or underinsured, which can lead to delayed or forgone treatment, poorer long-term health outcomes, and increased financial distress.

Key provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)—including the establishment of Marketplace coverage, protections against coverage denial or increased premiums due to preexisting conditions, removal of lifetime and annual coverage limits, Medicaid expansion in participating states, and extension of dependent coverage to age 26—play a critical role in increasing access to insurance and health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer (531)Kirchhoff AC, et al. (2024) J Natl Cancer Inst, 116: 1466.. However, ongoing efforts to roll back or repeal parts of the ACA threaten to undo these important protections, making it harder for adult survivors of pediatric cancer to get and keep health insurance. Such changes would likely exacerbate existing disparities in survivorship care and outcomes, particularly among survivors from low-income, rural, and racial/ethnic minority populations who already face barriers to accessing consistent, high-quality care (see Sidebar 19).

Advances in Pediatric Cancer Survivorship

Over the past several decades, progress in pediatric oncology has shifted from improving survival to also enhancing long-term quality of life. Historically, pediatric cancer treatment often relied on high doses of chemotherapy and radiation, which saved lives but left many survivors with serious late effects, including CVD, SPCs, and premature mortality. Today, therapies are increasingly tailored to each child’s clinical and biological features, helping to reduce toxicities without compromising survival (see Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment). At the same time, advances in genomics are revealing why some survivors are more vulnerable than others to treatment-related complications. These advances are transforming pediatric cancer survivorship care, paving the way for safer treatments today and more personalized care in the years ahead.

Reducing Treatment-related Toxicities

Growing awareness of late effects, together with advances in pediatric cancer biology, imaging, and supportive care, has altered both the prevalence and nature of treatment-related morbidity and mortality. In recent decades, advances in pediatric oncology have focused not only on treating childhood cancers, but also on reducing the long-term toxicities of therapy. Evidence of the long-term harms of intensive therapies prompted therapeutic modifications that reduced harmful exposures while maintaining efficacy.

The benefits of these therapeutic modifications to reduce harmful exposures have been documented in long-term survivor studies. In an analysis of more than 23,000 survivors, the 20-year cumulative incidence of severe or life-threatening chronic conditions declined from 33 percent among those diagnosed in the 1970s to 27 percent among those diagnosed in the 1990s, largely due to reductions in endocrine-related disorders and SPCs (538)Gibson TM, et al. (2018) Lancet Oncol, 19: 1590.. Similarly, a landmark study of more than 34,000 survivors diagnosed between 1970 and 1999 found that survivors treated in the 1990s experienced nearly a 50 percent lower risk of treatment-related mortality compared to those treated in the 1970s—a trend that paralleled declines in the use of cranial radiation for ALL, chest radiation for Hodgkin lymphoma, abdominal radiation for Wilms tumor, and reductions in cumulative anthracycline exposure (15)Armstrong GT, et al. (2016) N Engl J Med, 374: 833.. These improvements in morbidity and mortality have also translated into longer life expectancy (22)Yeh JM, et al. (2020) JAMA Oncol, 6: 350..

A key advancement underpinning these improvements is risk-stratified therapy, or the tailoring of treatment intensity to the clinical and biological features of each child’s cancer. For example, in a study of more than 6,000 pediatric ALL survivors, those classified as standard-risk and treated with contemporary regimens in the 1990s had lower rates of health-related mortality, SCPs, and chronic health conditions compared with survivors treated in the 1970s. Notably, the risk of late mortality and SPCs among survivors treated with 1990s standard-risk regimens were comparable to those of the general population, demonstrating that reductions in treatment intensity over recent decades have not compromised long-term survival (539)Dixon SB, et al. (2020) J Clin Oncol, 38: 3418..

New strategies are being tested to prevent late effects among survivors who remain at high risk. For example, women who received chest radiation during childhood or young adulthood face breast cancer risks that are comparable to those of BRCA gene mutation carriers. A randomized phase II clinical trial tested whether low-dose tamoxifen (Nolvadex), a drug that blocks estrogen, could reduce breast cancer risk in this population (540)Bhatia S, et al. (2021) Clin Cancer Res, 27: 967.. The study found that women taking low-dose tamoxifen showed a reduction in dense breast tissue visible on mammograms and circulating insulin-like growth factor levels, both established markers of breast cancer risk, without causing serious side effects. These results suggest that low-dose tamoxifen may represent a safe and effective preventive option for certain high-risk groups.

Certain chemotherapy drugs, known as anthracyclines, used to treat pediatric cancers can increase the risk of developing heart problems later in life. This treatment-related heart damage may not appear until years after treatment completion and can lead to long-term complications such as cardiomyopathy (weakening of the heart muscle) or heart failure. Multiple studies show that cumulative anthracycline doses above a certain level can increase the risk of cardiotoxicity, though more recent research suggests that no dose is entirely safe (470)Bates JE, et al. (2019) J Clin Oncol, 37: 1090.(541)Mulrooney DA, et al. (2009) BMJ, 339: b4606.. Consequently, many contemporary pediatric chemotherapy regimens restrict cumulative anthracycline doses to reduce the likelihood of long-term cardiac complications.

To further reduce risk, a cardioprotective medication called dexrazoxane (Zinecard) was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1991 to prevent chemotherapy-related heart damage in adults with certain cancers. Since then, studies in pediatric patients have shown that dexrazoxane significantly lowers the long-term risk of cardiac complications without reducing the effectiveness of cancer treatment (542)Chow EJ, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 2248.(543)Asselin BL, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 854.. In 2014, FDA granted orphan drug designation to dexrazoxane for the prevention of cardiomyopathy in pediatric and adolescent patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

Pediatric patients who receive chemotherapy are also at an increased risk of developing hearing loss, also called ototoxicity. One study found that 75 percent of children under the age of five and 48 percent of children over the age of five who were treated with cisplatin had hearing loss related to their treatment (544)Meijer AJM, et al. (2022) Cancer, 128: 169.. In September 2022, FDA approved sodium thiosulfate (Pedmark) to reduce the risk of hearing loss associated with the chemotherapeutic cisplatin in pediatric patients. Sodium thiosulfate reduced the risk of cisplatin-associated hearing loss by almost 60 percent compared to those who did not receive the drug (545)Brock PR, et al. (2018) N Engl J Med, 378: 2376.. A recent analysis of clinical trial data found that sodium thiosulfate provided the greatest protection in the groups most vulnerable to hearing loss from cisplatin—children under five and those with hepatoblastoma, medulloblastoma, or neuroblastoma—reducing their risk by up to 80-90 percent (546)Ohlsen TJD, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31479.. Additional research has also shown that the drug is safe and effective in everyday clinical use, further supporting its role in protecting young patients from the long-term effects of treatment (547)Ma J, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31631..

Genetic Susceptibility to Late Effects of Cancer Treatment

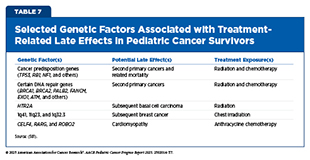

Although treatment exposures are the predominant drivers of late effects, researchers have found that not all survivors are equally affected. Over the past decade, rapid advances in molecular profiling have enabled researchers to identify

genetic factors that influence survivors’ risk of late effects (see Table 7).

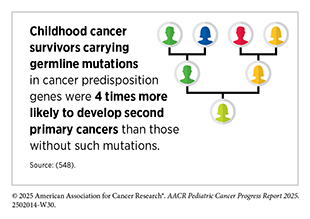

Large survivorship studies have shown that rare germline mutations—inherited changes in cancer predisposition genes that strongly increase cancer risk—such as TP53 and RB1, are more common among survivors than in the general population (475)Wang Z, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 2078.(501)Wang Z, et al. (2025) Nat Rev Cancer, 25: 129.(548)Zhou L, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol: JCO2500542.(549)Kim J, et al. (2021) JNCI Cancer Spectr, 5.. A growing body of research indicates that these germline mutations not only drive the development of certain pediatric cancers but also appear to increase survivors’ chances of developing SPCs later in life (see Germline Variants in Cancer Predisposition Genes) (501)Wang Z, et al. (2025) Nat Rev Cancer, 25: 129.. Importantly, carriers of these mutations face both a higher likelihood of SPC occurrence and increased SPC-related mortality.

Mutations in genes involved in DNA repair pathways (e.g., BRCA1/2, FANCM, and EXO1) can further magnify risks of SPCs, particularly when combined with treatment exposures (501)Wang Z, et al. (2025) Nat Rev Cancer, 25: 129.(550)Qin N, et al. (2020) J Clin Oncol, 38: 2728.(551)Morton LM, et al. (2020) JCO Precis Oncol, 4.. Mutations in DNA repair genes can impair the body’s ability to correctly repair DNA damage caused by therapies such as radiation and/or chemotherapy, increasing the likelihood of developing SPCs. For example, female survivors with such mutations who also received chest radiation or cytotoxic chemotherapy had more than a four-fold higher risk of developing breast cancer in adulthood compared to women without these mutations (550)Qin N, et al. (2020) J Clin Oncol, 38: 2728.. In addition to rare germline mutations, genome-wide association studies have also identified more common genetic variants or inherited differences in DNA sequence, predisposing pediatric survivors to SPCs, including radiation-induced breast cancer (1q41) and basal cell carcinoma (HTR2A) (552)Morton LM, et al. (2017) J Natl Cancer Inst, 109.(553)Sapkota Y, et al. (2019) J Invest Dermatol, 139: 2042..

Inherited susceptibility also contributes to a broad spectrum of other late effects. For example, genetic variants in genes regulating cardiac muscle contraction and drug metabolism (e.g., CELF4, GSTM1, and ROBO2) have been associated with an increased risk of chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy (554)Wang X, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 1758.(555)Wang X, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 863.(556)Singh P, et al. (2020) Cancer, 126: 4051.. Additional genetic associations have been identified for neurocognitive dysfunction, gonadal impairment, stroke, diabetes, and obesity, underscoring the broad influence of genetic background on survivorship outcomes (501)Wang Z, et al. (2025) Nat Rev Cancer, 25: 129.. Together, these findings highlight the importance of integrating genetic information with treatment history to more accurately identify survivors at highest risk for late effects and to inform precision survivorship care.

Care Coordination Across the Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Continuum

The multifaceted nature of pediatric cancer treatment necessitates comprehensive survivorship care that addresses the wide range of needs survivors face as they grow and age. These needs include support during the transition from pediatric to adult health services, coordination of routine and specialty appointments, monitoring for late effects, and assistance with psychosocial challenges. However, children and AYAs with cancer are often ill-equipped to navigate a complex health care system on their own, leaving critical survivorship needs unmet.

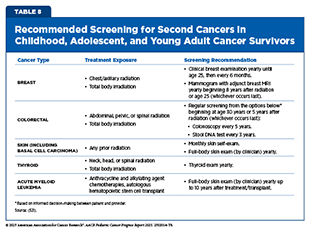

In recognition of these challenges, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) developed the Long-Term Follow-Up (LTFU) Guidelines to provide a standardized, evidence-based framework for survivorship care for children and AYAs (557)Landier W, et al. (2004) J Clin Oncol, 22: 4979.. Organized by the organ system and therapeutic exposure, the guidelines provide detailed recommendations for clinical evaluations, screening intervals, diagnostic testing, and preventive health counseling. Importantly, the guidelines also include recommendations for the early detection of SPCs in survivors at elevated risk based on their prior treatments (see Table 8). First released in 2003, the COG LTFU Guidelines have been regularly updated to reflect new evidence and evolving treatment practices, with the most recent version published in 2023 (558)DeVine A, et al. (2025) JAMA Oncol, 11: 544..

The COG LTFU Guidelines are designed with three primary aims: to provide evidence-based recommendations for the screening and management of treatment-related late effects; to increase awareness of potential complications among health care providers and survivors; and to standardize and improve the quality of survivorship care across clinical settings. By offering a structured, risk-based framework, the COG LTFU Guidelines enable clinicians to anticipate, identify, and manage a wide spectrum of late effects in a proactive manner (559)Hudson MM, et al. (2021) Pediatrics, 148.. The guidelines also serve as a critical resource for educating survivors and their families, empowering them to engage in their care by improving awareness of risks and preventive strategies.

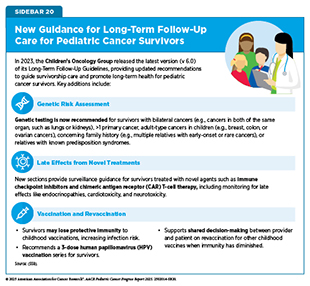

The most recent update reflects the evolving landscape of pediatric cancer care, introducing recommendations for genetic predisposition surveillance, monitoring after exposure to novel therapies, and updated vaccination practices (see Sidebar 20) (558)DeVine A, et al. (2025) JAMA Oncol, 11: 544.. Collectively, the COG LTFU Guidelines have advanced both the science and practice of survivorship care and remain the most widely adopted framework for addressing the complex, lifelong health needs of childhood and AYA cancer survivors.

Although many survivorship resources exist, access to high-quality survivorship care remains a challenge for pediatric survivors. For example, a 2017 survey of COG institutions found that while nearly all centers (96 percent) offered pediatric survivorship care, fewer than three-quarters of eligible survivors utilized these services (560)Effinger KE, et al. (2023) J Cancer Surviv, 17: 1139.. Similarly, in a study of more than 900 childhood cancer survivors, over half had not attended a cancer-related follow-up visit within the past two years and did not plan to have one within the next two years (561)Ford JS, et al. (2020) Cancer, 126: 619.. Adherence to guideline-recommended surveillance among pediatric cancer survivors is also poor. A recent study found that only about one-third of survivors received recommended screening for late effects, such as cardiomyopathy, thyroid dysfunction, or breast cancer (562)Milam J, et al. (2024) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 71: e31328..

As pediatric cancer survivors age, coordinated care is often complicated by care transitions, including the transition from oncology to long-term survivorship care, as well as the transition from pediatric to adult health care. Differences in the structure of pediatric versus adult-oriented health care can place survivors at risk for disengagement and loss to follow-up. Furthermore, many pediatric cancer centers do not have formal plans or systems in place to guide survivors as they transition from pediatric to adult care. A national survey of COG institutions found that while most programs eventually transfer survivors to another institution for adult cancer-related follow-up, few provide comprehensive resources to aid in successful health care transition (563)Marchak JG, et al. (2023) J Cancer Surviv, 17: 342.(564)Sadak KT, et al. (2019) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 66: e27793.. Barriers to transitioning from pediatric to adult survivorship care included a perceived lack of knowledge about late effects among clinicians and survivor reluctance to transfer care (563). Structural barriers, such as insufficient funding for survivorship program development and oncology workforce shortages, further limit the delivery of high-quality care (560)Effinger KE, et al. (2023) J Cancer Surviv, 17: 1139.(565)Jacobs LA, et al. (2017) Lancet Oncol, 18: e19.. These challenges are compounded by adversities related to social drivers of health, such as poverty, inadequate insurance coverage, and living long distances from survivorship clinics, all of which are associated with a lower likelihood of receiving recommended follow-up care (566)Gilbert R, et al. (2025) Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 13: 180..

Recognition of the critical role that primary care providers (PCPs) play in survivorship is growing, because they are well-positioned to manage comorbidities, deliver preventive care, and support long-term health and well-being. However, research shows persistent challenges in fully integrating PCPs into survivorship care. In one survey, fewer than half of pediatric PCPs reported feeling comfortable independently providing health maintenance to pediatric cancer survivors (567)Wadhwa A, et al. (2019) Cancer, 125: 3864.. Evidence shows that PCPs frequently report limited knowledge of survivorship care and a need for additional training before they feel confident providing care to survivors (568)Nekhlyudov L, et al. (2017) Lancet Oncol, 18: e30..

However, PCPs report that their comfort level providing survivorship care increased substantially when care was provided in collaboration with pediatric oncologists. Comfort levels were highest when PCPs worked as a part of a multidisciplinary team, underscoring the value of shared care models—an approach in which oncologists and PCPs actively collaborate with oncologists to deliver comprehensive survivorship care (569)Bradford N, et al. (2024) J Cancer Surviv.. Beyond provider knowledge, systemic barriers such as inadequate reimbursement incentives, poor communication between oncology and primary care, and lack of accessible survivorship guidelines also hinder integration. Experts have suggested new strategies, such as training PCPs with added survivorship expertise, and testing payment incentives that reward coordinated, comprehensive care (568)Nekhlyudov L, et al. (2017) Lancet Oncol, 18: e30.. However, these strategies remain underdeveloped and inconsistently applied.

Survivors themselves report similar concerns. In a large survey of adult survivors of childhood cancer, 87 percent reported having a PCP, yet only 33 percent had ever seen that provider for a cancer-related concern (561)Ford JS, et al. (2020) Cancer, 126: 619.. Confidence in PCP cancer expertise was low, with only about one-third of survivors believing their provider could adequately manage cancer-related issues.

Survivorship care plans (SCPs) are one effective tool for improving care coordination among pediatric cancer survivors. SCPs typically include a summary of the patient’s diagnosis and treatment, follow-up care recommendations, and guidance on managing long-term effects. SCPs serve as a critical bridge between pediatric oncology and primary care settings, promoting coordinated, continuous care as patients transition out of active treatment and into long-term survivorship care. Recent studies have shown that survivors who receive SCPs are more likely to adhere to recommended late effects screening (570)Yan AP, et al. (2020) J Clin Oncol, 38: 1711.. Unfortunately, SCPs are often underutilized by PCPs, who cite lack of clarity, insufficient training, and competing demands as barriers to their utility (571)Iyer NS, et al. (2017) Support Care Cancer, 25: 1547..

The Passport for Care (PFC), a web-based clinical decision support tool developed in collaboration with COG, has demonstrated effectiveness in helping PCPs generate and deliver SCPs to pediatric cancer survivors (572)Children’s Oncology Group. Passport for Care. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Launched in 2007, PFC integrates patient diagnosis and treatment histories with the latest COG LTFU Guidelines to create individualized SCPs. Beyond SCP generation, PFC also serves as a secure platform that enables both clinicians and survivors to access, update, and share health information to support care coordination.

In a survey of clinicians, PFC was most commonly used to create individualized SCPs and guide surveillance, with nearly 70 percent of clinicians reporting that PFC substantially improved adherence to the COG LTFU guidelines (573)King JE, et al. (2023) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 70: e30070.. As of May 2022, 54 percent of COG-affiliated survivorship clinics providing late effects services to childhood cancer survivors were enrolled in the PFC program. Ongoing efforts to expand PFC adoption focus on reducing implementation barriers by streamlining data entry through integration with electronic health records and by enhancing educational content delivery through technological innovations, including the development of a mobile health application to strengthen survivor engagement.

In addition to SCPs, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) offer another valuable tool for enhancing coordination and ensuring that the survivor’s perspective remains central to care. PROs are reports provided directly by patients about their health status without interpretation by clinicians or caregivers (574)Leahy AB, et al. (2020) JAMA Pediatr, 174: e202868.(575)Yan AP, et al. (2025) EJC Paediatric Oncology, 5.. PROs provide critical insights into patient symptoms, functional status, and quality of life, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of treatment tolerability and overall well-being.

In pediatric oncology, PROs are typically collected through age-appropriate questionnaires or electronic platforms that ask children and adolescents about their symptoms, daily functioning, and psychosocial well-being during and after treatment (576)Reeve BB, et al. (2023) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 43: e390272.. Increasingly, PROs are administered electronically, offering advantages such as real-time data capture, integration with clinical records, and automated alerts to care teams (575)Yan AP, et al. (2025) EJC Paediatric Oncology, 5.(577)Perry MB, et al. (2024) J Med Internet Res, 26: e49089.. Such tools allow clinicians to track changes in symptoms over time, enabling them to tailor care to the child’s evolving needs. Research demonstrates that many children can reliably self-report their experiences beginning around age eight (578)Tomlinson D, et al. (2019) BMC Cancer, 19: 32.(579)Horan MR, et al. (2022) Children (Basel), 9.. When self-report is not feasible, such as in case of very young children or those too ill to complete questionnaires, parents or other caregivers may provide proxy reports to complement or substitute for the child’s perspective (576)Reeve BB, et al. (2023) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 43: e390272.(580)Tomlinson D, et al. (2023) BMJ Support Palliat Care, 13: e469..

A growing body of research highlights the value of incorporating PROs into pediatric oncology care. Two large-scale randomized controlled trials in pediatric cancer patients demonstrated that electronic PRO monitoring improved recognition and management of symptoms (581)Dupuis LL, et al. (2025) JAMA Pediatr, 179: 11.(582)Dupuis LL, et al. (2024) JAMA, 332: 1981.. PROs are also increasingly being used in pediatric palliative and supportive care, where they empower children to share their experiences directly with providers. Families and clinicians report that PROs strengthen communication and foster a greater sense of partnership in care (583)Rusconi D, et al. (2024) J Palliat Care, 39: 298.(584)Merz A, et al. (2023) J Pain Symptom Manage, 66: e327.. Use of PROs are particularly valuable in sensitive contexts such as end-of-life care, where monitoring and responding to the child’s symptoms and quality of life are especially critical.

Despite clear benefits, PROs remain underutilized in pediatric oncology research and practice . An analysis of FDA approvals for pediatric oncology products between 1997 and 2020 found PRO data in only 4 of 17 submissions (24 percent) (585)Murugappan MN, et al. (2022) J Natl Cancer Inst, 114: 12.. Similarly, another study reported that fewer than half (44 percent) of registered clinical trials evaluating supportive care interventions for children with cancer incorporated PROs, underscoring their limited use across both drug development and supportive-care research (586)Rothmund M, et al. (2022) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 176: 103755..

Barriers contributing to underuse of PROs in pediatric oncology include limited clinician training, technological constraints, and disparities in digital access and literacy across families (576)Reeve BB, et al. (2023) Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book, 43: e390272.(587)Colbert JA, et al. (2025) JAMA Oncol, 11: 233.. Addressing these gaps will require investment in infrastructure, clinician training, and ongoing validation of PRO tools for diverse populations. Incorporating PROs into standard pediatric oncology care represents a meaningful step toward more patient- and family-centered cancer care. As the evidence continues to grow, prioritizing PRO integration will help ensure that the voices of pediatric patients remain central to guiding treatment decisions and improving care.

Beyond PROs, digital health interventions—including virtual reality, mobile applications, computer programs, video games, and other interactive platforms—have emerged as effective tools by supporting symptom management, promoting health education, and expanding access to resources and services. A recent analysis showed that these tools eased pain, nausea, anxiety, distress, and fear, while also improving quality of life for pediatric cancer survivors (588)Zhao B, et al. (2025) J Cancer Surviv..

Models of care coordination offer promising approaches to further improve care continuity for pediatric cancer survivors. Researchers emphasize that effective models incorporate multidisciplinary collaboration, patient navigators, and family-centered services tailored to survivor needs (589)Wong CL, et al. (2024) BMJ Open, 14: e087343.. Programs that integrate psychosocial support, health education, PROs, and financial assistance within long-term follow-up frameworks may improve the quality and continuity of care for pediatric cancer survivors.

Supporting Parents and Other Caregivers

A diagnosis of pediatric cancer profoundly affects the parents and caregivers who take on the primary responsibility for the child’s medical and psychosocial care throughout treatment and survivorship. These responsibilities include managing medications, attending medical visits, providing emotional support, and navigating complex health care systems. As a result, parents and caregivers often experience heightened psychological strain and disruptions to their overall well-being.

Research shows that parents of children with cancer are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress than the general parent population, with prevalence estimates of 21 percent, 28 percent, and 26 percent, respectively (590)van Warmerdam J, et al. (2019) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 66: e27677.. Parents are also more likely to utilize mental health services for anxiety and depression following their child’s diagnosis than parents of children without cancer (591)Hu X, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e244531..

Unmanaged caregiver distress has consequences that extend beyond the individual. High levels of distress not only affect the well-being of caregivers, including parents, but are also linked to poorer outcomes for children. Studies indicate that caregiver distress is closely tied to children’s health-related quality of life, with higher caregiver distress predicting poorer physical and psychosocial outcomes in pediatric patients (592)Pierce L, et al. (2017) Psychooncology, 26: 1555..

Beyond the psychological toll, caring for a child with cancer places immense strain on parents’ economic and professional lives. Following a pediatric cancer diagnosis, many parents face job loss, reduced work hours, or other disruptions to employment, often leading to long-term financial insecurity (593)Roser K, et al. (2019) Psychooncology, 28: 1207.. Studies reveal that approximately 60 percent of parents and/or caregivers experience financial hardships following a pediatric cancer diagnosis (594)Santacroce SJ, et al. (2020) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 67: e28093.(595)Evans EM, et al. (2023) Pediatr Blood Cancer: e30496.. Material hardships, such as food, housing, and energy insecurity (i.e., the inability to adequately meet basic household energy needs) are common and disproportionately affect families from disadvantaged backgrounds (595)Evans EM, et al. (2023) Pediatr Blood Cancer: e30496.. In response, parents often adopt coping strategies such as incurring debt or reducing spending, while barriers to assistance programs leave vulnerable groups at heightened risk for financial hardship (596)Lin JJ, et al. (2024) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 71: e30890.. Together, these findings highlight the interconnected psychological and financial pressures facing parents and caregivers of children with cancer, reinforcing the need for comprehensive psychosocial and economic support throughout the cancer care continuum.

In recognition of these challenges, the pediatric oncology field has advanced efforts to define and improve psychosocial services for pediatric cancer patients and their families and caregivers. In 2015, an interdisciplinary group of clinicians, researchers, and parent advocates established Psychosocial Care for Children with Cancer and Their Families, which outlined 15 evidence-based Standards to ensure consistent, high-quality psychosocial care (597)Wiener L, et al. (2015) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 62 Suppl 5: S419.. These Standards address a wide range of psychosocial needs, including assessment of distress, parental mental health, school reintegration, adherence to treatment, and bereavement support. The overarching goal was to provide a framework to ensure that all families, regardless of treatment setting, receive high-quality psychosocial services alongside medical care (597)Wiener L, et al. (2015) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 62 Suppl 5: S419..

Despite the endorsement of these Standards by numerous professional organizations, implementation into routine clinical practice has been slow. A 2016 survey of pediatric oncology programs found that while most programs offered some psychosocial services, many lacked the full range of specialized providers needed to deliver comprehensive care (598)Scialla MA, et al. (2017) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 64.. While more than 90 percent of pediatric oncology programs employed social workers and child life specialists (i.e., professionals who help children and families cope with the stress of cancer and treatment), fewer had psychologists (60 percent), neuropsychologists (31 percent), or psychiatrists (19 percent). Psychosocial care was also frequently provided reactively after problems were identified rather than systematically across all patients (598)Scialla MA, et al. (2017) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 64.. Notably, only about half of pediatric oncologists described the care at their centers as comprehensive and state-of-the-art (599)Scialla MA, et al. (2018) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 65..

A follow-up assessment in 2023 showed modest improvements. Nearly all programs reported access to social workers (97.2 percent) and child life specialists (92.5 percent), but psychologists (69.2 percent), neuropsychologists (39.3 percent), and psychiatrists (15.0 percent) were still far less common (600)Scialla MA, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31676.. The median staffing ratios remained concerning, with one full-time equivalent (FTE) psychologist per 100 patients and one FTE psychiatrist per 200 patients. Although progress has been made, many centers continue to lack the breadth and depth of staffing necessary to fully implement the Standards. Persistent barriers include limited funding, inadequate institutional resources, and workforce shortages.

To support wider adoption, implementation tools have been developed to help programs evaluate and strengthen their psychosocial services. These resources include structured frameworks for assessing a program’s level of implementation, rating quality of care, and identifying specific action steps and resources for improvement (601)Wiener L, et al. (2020) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 67: e28586.. Together, these initiatives reflect ongoing progress in aligning psychosocial services with the published Standards. Continued investment in staffing, resources, and implementation strategies are essential to ensure that all children with cancer, along with their families and caregivers, receive the comprehensive psychosocial support needed to promote resilience, enhance quality of life, and improve long-term outcomes.

Next Section: Understanding the Global Landscape of Pediatric Cancers Previous Section: Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment