Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research and Patient Care Through Evidence-Based Policies

In this section, you will learn:

- Sustained and robust investment in federal agencies and programs is vital to advancing pediatric cancer research and training the future workforce.

- Targeted legislative and policy efforts are helping pediatric cancer patients live longer, healthier lives.

- Global collaboration and partnerships are essential for accelerating the development of safe and effective therapies for pediatric cancer patients, including through innovative clinical trials that deliver meaningful impact.

Pediatric cancers pose unique challenges compared to adult cancers, but scientific advances continue to improve overall life expectancy, with marked increases in 5-year survival rates for pediatric cancers from 63.1 percent in the 1970s to 85.2 percent in the 2010s (see Pediatric Cancer Trends in the United States). This remarkable progress against pediatric cancer has been facilitated by beneficial legislation and federal policies. Additionally, Department of Health and Human Services agencies including the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are playing key roles in furthering pediatric cancer research and continuing to improve patient outcomes.

Unfortunately, the burden of pediatric cancer remains high, as about 15,000 individuals under age 20 are diagnosed with cancer in the United States every year and cancer remains the leading cause of death by disease for children (16)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.. Moreover, advances in treatment and improved survival are not uniform across pediatric cancer types, and survival rates remain low for certain diagnoses (see Uneven Progress Against Pediatric Cancers). As more children continue to live longer after a cancer diagnosis, addressing the specific needs of long-term survivors will require increased research. NCI-sponsored programs like the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study are also critical for identifying and combating the long-term effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment experienced by pediatric cancer survivors (761)Robison LL, et al. (2009) J Clin Oncol, 27: 2308..

Investing in Pediatric Cancer Research to Secure a Healthier Future

Robust and sustained federal investments in pediatric cancer research and patient care infrastructure are required to translate scientific advances into improved outcomes for children with cancer. NIH and NCI are global leaders for pediatric cancer research and support numerous grants, programs, and initiatives. For example, NIH and NCI provide federal grants for investigator-initiated research, and NCI also supports critical collaborations such as the Children’s Oncology Group and the Pediatric Early Phase Clinical Trials Network. At NCI, pediatric oncologists and scientists across disciplines also conduct pediatric cancer research through NCI’s intramural research program, including the NCI Center for Cancer Research Pediatric Oncology Branch and the Division of Cancer

Epidemiology and Genetics. In addition, NIH and NCI manage $28 million for Childhood Cancer Survivorship, Treatment, Access, and Research (STAR) Act initiatives and $50 million for the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (CCDI) each fiscal year (FY) (762)National Cancer Institute. NCI Budget Fact Book. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. The STAR Act is authorized through FY 2028, and both STAR Act and CCDI funds must be appropriated by the US Congress each year. The CCDI was launched in FY 2020 as a special 10-year initiative proposed in the President’s Budget Request, and Congress has appropriated the proposed funds each fiscal year since (309)Flores-Toro JA, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 4045.(763)National Cancer Institute. An Analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Investment in Pediatric Cancer Research. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. In recognition of CCDI’s impact, the Trump administration recently proposed that CCDI annual funding be doubled from $50 million to $100 million to support an expansion and increased focus on integrating artificial intelligence tools and approaches to advance pediatric cancer research (764)OncoDaily. Trump Signs Executive Order Doubling AI Funding for Pediatric Cancer Research. Accessed: October 8, 2025..

Federal funding for pediatric cancer research is critical for obtaining and maintaining necessary laboratory facilities and equipment as well as supporting the scientific workforce and the staffing needed for clinical trials conducted in the spectrum of rare diseases that comprise childhood cancers. Universities and academic medical centers at the forefront of cutting-edge pediatric cancer research rely on federal funding to fuel their efforts and train the next generation of researchers and clinicians. Indirect cost support is essential for covering the infrastructure and administrative expenses that make scientific discoveries possible. Indirect costs include maintaining laboratory equipment, ensuring compliance with safety and ethical standards, and supporting essential research staff. Without adequate reimbursement for indirect costs, research institutions will struggle to sustain the environment needed for groundbreaking pediatric cancer studies. Challenges to the pediatric physician–scientist workforce include the lack of structured and robust mentorship, significant personal financial opportunity cost, and inadequate research funding (765)The Future Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Workforce: Meeting the Needs of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Washington (DC)2023.. One survey of pediatric cancer physicians found that a lack of institutional funding was considered the top barrier facing the workforce (754)Hastings C, et al. (2023) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 70: e30221.. Moreover, developing a sustainable pediatric cancer research workforce also requires building a diverse workforce equipped to address health disparities and the needs of a diverse patient population (766)Winestone LE, et al. (2023) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 70 Suppl 6: e30592.. Importantly, pediatric cancer research output over the past decade, as measured by publications, has not kept pace with other pediatric diseases or cancer research overall and accounts for less than 5 percent of all cancer research output (767)Syrimi E, et al. (2020) JCO Glob Oncol, 6: 9.. Pediatric cancer research requires innovative and sometimes high-risk approaches that do not always fit traditional funding models. Employing more flexible grant structures would allow researchers to pivot as the field rapidly evolves, foster collaboration across disciplines, and accelerate discovery.

There are also inequities in the distribution of research funding for pediatric cancers. While pediatric cancer survival rates have significantly increased over time, these improvements have not been even across all disease areas, with the greatest advances occurring in hematologic malignancies (768)Siegel RL, et al. (2022) CA Cancer J Clin, 72: 7.. For example, the 5-year survival rate for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), an aggressive form of brain cancer, remains below 3 percent (28)Hoffman LM, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 1963.. Research dedicated to some rare pediatric cancers was found to receive less funding than expected based on their disease burden (769)Rees CA, et al. (2021) JAMA Pediatr, 175: 1236.. In addition, there remains an urgent need for more funding for research related to survivorship and quality of life care, health disparities, infrastructure, and technology. A recent analysis found that while nearly one-third of all survivorship research focuses on pediatric cancer, very few studies focus on long-term survivors, adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors, or adult survivors of pediatric cancers (770)Gallicchio L, et al. (2025) Cancer Causes Control, 36: 587..

Overall, it is difficult to accurately estimate federal pediatric cancer research investment. NIH funding and NCI funding are reported for pediatric cancer broadly but do not include detailed breakdowns or fully capture investments in basic research and other cross-cutting efforts, and many other federal agencies such as the Department of Defense do not release specific funding information. Likewise, it is difficult to characterize the pediatric cancer research workforce due to limited data and coordination between funding entities and employers. Increased study and tracking of pediatric cancer research funding and workforce trends would help reveal challenges and better inform policy solutions. One historical analysis found that only 4 percent of federal cancer research funding goes to studying cancer in children and AYAs (763)National Cancer Institute. An Analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Investment in Pediatric Cancer Research. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Furthermore, pharmaceutical companies are less likely to invest in pediatric cancer drug development and clinical trials due to the smaller patient population, limited market potential, and strict regulatory requirements (771)Rahimzadeh V, et al. (2022) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 69: e29854.. Therefore, any cuts to federal agencies and their programs would disproportionately impact pediatric cancer research, as combined public and philanthropic funding commitments to pediatric cancer are already considered inadequate and have been in decline (665)Loucaides EM, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: e672.. The consequences of recent disruptions to NIH and NCI funding are already being felt by pediatric cancer patients (772)Children’s Brain Tumor Project. Long-Standing Consortium, PBTC, Loses Federal Funding. Accessed: August 31, 2025.(773)American Journal of Managed Care. Childhood Cancer Awareness Month Spotlights Barriers That Persist in Care. Accessed: September 30, 2025..

Policies Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research and Care

Past investments, support, and legislative actions from the US government have played a crucial role in accelerating progress against pediatric cancer. Bipartisan congressional efforts in both the House and Senate, including champions within the Congressional Childhood Cancer Caucus, have been key to many of the past decade’s achievements, especially in expanding pediatric cancer data collection, building research infrastructure, and accelerating drug development (see Sidebar 26).

Pediatric cancers are rare, which poses significant challenges for drug development, compared to other diseases. FDA

has only issued roughly 100 pediatric cancer drug approvals ever, while there have been over 300 approvals in oncology overall since 2020 (774)US Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Oncology Drug Approvals. Accessed: August 31, 2025.(775)US Food and Drug Administration. Oncology (Cancer)/Hematologic Malignancies Approval Notifications. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Moreover, although studies have shown that approximately 30 percent of children with high-risk cancers have molecularly targetable findings, only 13.1 percent were receiving matched targeted therapies (163)Parsons DW, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2224.. Legislation encouraging and facilitating pediatric cancer drug development has been one crucial way the US federal government has sought to bridge these gaps.

The landmark Creating Hope Act of 2011 incentivized pharmaceutical companies to develop drugs for rare pediatric diseases by expanding FDA’s Priority Review Voucher (PRV) program. Specifically, the updated PRV program allowed pharmaceutical companies to expedite FDA review of more profitable drugs in return for the development of treatments that combat rare pediatric diseases, including cancer. Between 2012 and 2024, four PRVs were granted for drugs that treat pediatric cancer (776)National Organization of Rare Diseases. Impact of the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program on Drug Development 2012 – 2024. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. A reauthorization of this essential piece of legislation, H.R.7384 Creating Hope Reauthorization Act of 2024 (777)Congress.GOV. H.R.7384 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Creating Hope Reauthorization Act of 2024. Accessed:, would incentivize the continued development of new medications and treatments for pediatric cancer patients.

In 2003, the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA) passed, requiring sponsors of new drug applications or biologics license applications to submit assessments to FDA regarding potential applications for pediatric patients. However, the original law exempted therapeutics with orphan designations, which excluded almost all pediatric cancer studies since 75 percent (103 out of 137) of new drug and biologics applications for oncology received an orphan designation since 2013 (778)Friends of Cancer Research. Assessing the Impact of the Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity (RACE) Act. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Introduced by Congressional Childhood Cancer Caucus Founder and Chair Representative Michael McCaul (R-TX), the Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity (RACE) for Children Act, signed into law in 2017 and first implemented in 2020, amended PREA and authorized FDA to direct companies developing cancer drugs in adult settings to study the effects of those drugs in pediatric patients when the molecular targets of the drug are relevant to pediatric cancers (779)Congress.gov. H.R.1231 – 115th Congress (2017-2018): RACE for Children Act. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Furthermore, the recently passed ORPHAN Cures Act encourages drug sponsors to investigate the utility of existing FDA-approved treatments in additional pediatric cancer settings. The RACE for Children Act has been credited for greater numbers of post-approval pediatric testing requirements and the earlier initiation of pediatric trials for new therapies (420)Liu ITT, et al. (2024) Pediatrics, 154.. No drugs approved between 2017 and 2020 had post-approval pediatric testing requirements. After enactment of the RACE for Children Act, from 2020 to 2024, 15 of 21 new adult drugs had required pediatric testing. However, while the RACE Act strengthened the requirements to conduct pediatric testing, it does not guarantee that the studies will be completed. Since there are limited enforcement mechanisms to ensure study completion and no mandate to develop these drugs further, it remains an open question whether there will be any notable increase in new drug approvals for pediatric populations.

Legislative actions have also promoted pediatric cancer research by enhancing the storing, harmonizing, and sharing of genomic and clinical data. The Gabriella Miller Kids First Research Act 2.0, a reauthorization of the 2014 act, ensures that research of pediatric cancer and structural birth defects remains an NIH priority. Named after Gabriella Miller, who died from an aggressive, deadly brain cancer (DIPG, mentioned above) in October 2013, this bill continues support for the Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program, including initiatives to perform sequencing on patients with pediatric cancer and structural birth defects and the comprehensive Kids First Data Resource Center (see Building and Connecting Data Networks) (780)Kids First Data Resource Center. About Kids First Data Resource Center. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. The Kids First Data Resource Center has enabled large-scale collaborative research that accelerates the translation of data into clinical insights (781)Kids First: A New Vision for Pediatric Research. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Initiatives like the Data for Pediatric Brain Cancer Act of 2023, introduced by Representative Mike Kelly (R-PA) and Representative Ami Bera, MD (D-CA), aim to further these efforts for pediatric brain cancer by creating a new registry to systematically collect and manage real-world data on pediatric brain tumors.

The STAR Act and the STAR Reauthorization Act furthered these efforts to facilitate pediatric cancer research by creating various new data collection and sharing initiatives (782)Alliance for Childhood Cancer. STAR Act : Legislative Activity. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. This multi-pronged act includes the expansion of NCI biospecimen collection and repository programs for pediatric cancers and additional support for studies related to pediatric cancer survivorship. It also funds state-level cancer registries through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to identify and track incidences of pediatric cancer and support the collection of cases into national cancer registries. Additionally, it requires that at least one pediatric oncologist be present on the National Cancer Advisory Board, a federal committee that advises the NCI Director on grants and policy to ensure that a focus on pediatric cancer remains at the forefront of NCI-supported research. The STAR Act has been credited for significantly expanding pediatric cancer research efforts, improving survivorship care, and enhancing data collection initiatives (783)Sadie Keller Foundation. Looking Back to the Passing of the STAR Act. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Through authorization of $30 million annually for pediatric cancer research programs, the STAR Act has also helped support many projects through the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) to collect data on rarer and understudied childhood cancers (784)Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tracking Pediatric and Young Adult Cancers. Accessed: August 31, 2025.(785)National Cancer Institute. Childhood Cancer STAR (Survivorship, Treatment, Access, Research) Act (Public Law No: 115-180). Accessed: August 31, 2025..

Following the STAR Act, the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative was established by NCI to increase data collection and sharing efforts across the pediatric cancer research community. Its goals include gathering data from every child and AYA regardless of where they receive care, creating a national strategy to accelerate molecular insights for diagnosis and treatment, and developing a platform and tools for researchers to utilize the data (309)Flores-Toro JA, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 4045.. The CCDI has expanded molecular profiling of pediatric cancers to better understand their unique tumor biology, driven therapeutic development, and built a critical data ecosystem that enables comprehensive data collection, sharing, and analysis (33)Jagu S, et al. (2024) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 71: e30745.. Through the CCDI Data Ecosystem, cancer researchers can further our understanding of pediatric cancers and investigate novel research questions.

These legislative and policy achievements, the result of extensive coordination between advocacy groups, health professionals, and policymakers, continue to make significant, tangible steps forward in pediatric cancer research and help accelerate the development of new and more effective treatments (420)Liu ITT, et al. (2024) Pediatrics, 154..

Applying Regulatory Science to Advance Pediatric Cancer Research and Care

FDA plays a central role in safeguarding public health by evaluating the safety and efficacy of medical products, including cancer therapies. In pediatric oncology, this responsibility is heightened by the urgent need to address rare, biologically distinct, and often aggressive cancers that occur in young patient populations, requiring tailored scientific and regulatory approaches to ensure that children benefit from advances in cancer research as quickly and safely as possible.

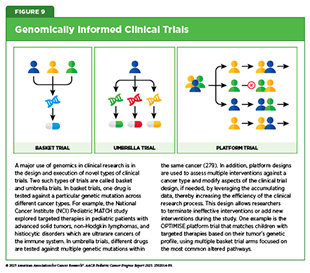

Within FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE), the Pediatric Oncology Program leads efforts to integrate pediatric considerations early in oncology drug development. The program engages industry sponsors, academic investigators, and patient advocates to evaluate the relevance of molecular targets to pediatric cancers; encourages inclusion of children and AYAs in clinical trials when appropriate; and supports innovative trial designs such as basket and platform studies (see Figure 9) (786)US Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Oncology Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement – 06/16/2023. Accessed: August 31, 2025.(787)US Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Oncology. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. A chief responsibility of the program is to maintain the Pediatric Molecular Targets List, which was required by the RACE Act to guide FDA in determining whether drug development programs will be subject to additional pediatric clinical studies required under PREA. These approaches help maximize the efficiency of pediatric trials and aim to reduce the lag time between approval of adult and pediatric indications.

The Pediatric Oncology Program also holds meetings with various stakeholders, including the Pediatric Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (786)US Food and Drug Administration. Pediatric Oncology Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement – 06/16/2023. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. The Pediatric Subcommittee was created in recognition of the unique scientific, clinical, and ethical considerations involved in pediatric oncology to provide a formal mechanism to bring pediatric expertise into the regulatory process. Composed of pediatric oncologists, biostatisticians, and patient advocates, among others, the subcommittee serves as a forum for reviewing pediatric study plans, assessing trial design feasibility, developing strategies to overcome enrollment challenges, and considering age-appropriate endpoints and dosing.

Through the agency’s coordinated efforts, FDA is working towards a regulatory framework that is scientifically rigorous, responsive to the unique needs of children and AYAs with cancer, and addresses the distinct challenges of rare pediatric cancers. By fostering collaboration among academic researchers, industry, and patient advocates, applying innovative trial designs, and ensuring that expert pediatric perspectives inform decision-making, the agency can help bring promising therapies to young patients faster, without compromising safety or efficacy.

The Next Decade: Challenges and Opportunities in Pediatric Cancer Research and Care

In the past decade, significant bipartisan US policymaking efforts have advanced pediatric cancer research and care. Scientific advances have dramatically increased survival for many patients, of even once incurable cancers. As pediatric cancers are rare, streamlined infrastructure, public–private partnerships, and international collaborations to support large multicenter clinical trials, biorepositories, and data-sharing projects have been crucial components underlying these successes (80)Gore L, et al. (2024) Cell, 187: 1584.. Despite notable progress, many challenges remain, including funding gaps, regulatory hurdles, and disparities in access and outcomes.

Pediatric cancer clinical trials face a multitude of barriers, including limited trial availability and eligibility, difficulties with enrollment, lack of adequately trained investigators and staff, financial constraints, and regulatory complexity (788)Mittal N, et al. (2022) Scientific Reports, 12: 3875.(789)Rivers Z, et al. (2023) Clin Ther, 45: 1148.. It is estimated that only one in five pediatric cancer patients is able to enroll in a clinical trial (273)Faulk KE, et al. (2020) PLoS One, 15: e0230824.. Despite the push for incentivizing pediatric cancer research, pediatric clinical trials have not significantly increased. Moreover, pediatric tumors differ greatly from adult tumors, and more research is needed to understand their unique biological underpinnings (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers) (790)Lupo PJ, et al. (2020) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 29: 1081.. Fully funded and nationally coordinated pediatric cancer screening and surveillance programs are also critical for the early detection of childhood cancers, which helps inform epidemiologic studies, increases our understanding of their unique biology, and improves treatment outcomes (see Pediatric Cancer Predisposition and Surveillance) (36)Brodeur GM, et al. (2025) Clin Cancer Res, 31: 2581..

Cancer care for pediatric patients also faces persistent challenges. Pediatric cancer patients and their families experience substantial negative financial impacts, which follow them into survivorship (see Financial Challenges) (791)Ohlsen TJD, et al. (2024) Support Care Cancer, 33: 36.(792)Di Giuseppe G, et al. (2023) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 183: 103914.. Financial support for patients and their families during and after treatment is critical for ensuring that children and adolescents with cancer have access to necessary care and specialized services such as psychosocial support (600)Scialla MA, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31676.. Another common barrier to care is the lack of hospitals or clinical trial sites that are equipped to serve pediatric patients within accessible travel distance. Such geographic limitations exacerbate disparities among underserved and rural populations and will require expanding the capabilities of local health care facilities or building new centers (417)Liu X, et al. (2023) JAMA Netw Open, 6: e2251524.. Moreover, understanding and mitigating the late effects of cancer treatment in children is an area in which further research is needed to improve the health and quality of life of the growing population of childhood cancer survivors (see Supporting Survivors of Pediatric Cancers) (476)Roganovic J (2025) World J Clin Cases, 13: 98000.. It is increasingly important for researchers and oncologists to consider the long-term and late effects of existing cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy, as well as newer cancer treatments, including novel targeted therapies, immunotherapies, cell and gene therapies, and combination regimens as they are developed to improve outcomes.

These challenges highlight the urgent need for continued action. Although past legislation and policies have stimulated industry productivity and the clinical development of new potential therapies for children, there is an opportunity for additional efforts to produce tangible advances in care and outcomes. Novel approaches to studying pediatric cancer that provide financial incentives for biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies to invest in childhood cancer therapies is a clear need. Additionally, simplifying the regulatory environment for drug development would be immensely beneficial. A meaningful opportunity exists over the next decade for stakeholders, including policymakers and the public, to further accelerate progress in pediatric cancer research and care.

Current Legislation Under Consideration

To address areas of unmet need in pediatric cancer, Congress has introduced several bills for consideration to spur increases in drug development and access to care. One potential legislation that would benefit pediatric cancer drug development is the Innovation in Pediatric Drugs Act of 2025 (793)Congress.gov. S.705 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): Innovation in Pediatric Drugs Act of 2025. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. This bill would modify existing pediatric drug laws like PREA and the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act to ensure timely completion of pediatric studies. Currently, under these laws, pediatric studies are required for certain new drugs designed for adult populations, but exemptions exist for rare diseases—which encompass indications for most new pediatric drugs. Enactment of the newly proposed legislation would enable FDA to close this loophole, penalize companies who fail to complete required pediatric studies in a timely manner, and provide funding for the study of older drugs approved for adults in children.

The Give Kids a Chance Act of 2025, introduced in the House by Representative McCaul (R-TX) and cosponsored in the Senate by Senator Mullin (R-OK) and Senator Michael Bennet (D-CO), contains provisions from four bills previously proposed but not yet passed, including the Innovation in Pediatric Drugs Act, Give Kids a Chance Act of 2024, the Creating Hope Reauthorization Act, and the Retaining Access and Restoring Exclusivity Act (794)Congress.gov. H.R.1262 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): Give Kids a Chance Act of 2025. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Together, this multi-part bill would remove multiple barriers in pediatric drug development. In addition to requiring pharmaceutical manufacturers to invest in drugs with potential indications for rare pediatric diseases by granting FDA greater authority to enforce pediatric study requirements, it also may require pharmaceutical companies to study drug combinations in children to help address the need for timely development of combinatorial trials. Moreover, this bill would reauthorize and strengthen the pediatric rare disease PRV program. Reauthorizing the PRV program for an additional 6 years would ensure that pharmaceutical companies developing drugs to treat pediatric cancers can expedite FDA review of more profitable drugs in their pipeline, powerfully incentivizing their development. Since the original Creating Hope Act was first passed into law in 2012, 53 PRVs have been awarded for 39 rare pediatric diseases (776)National Organization of Rare Diseases. Impact of the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher Program on Drug Development 2012 – 2024. Accessed: August 31, 2025..

Similarly, the Ensuring Pathways to Innovative Cures (EPIC) Act would modify the Inflation Reduction Act to enhance drug development for rare diseases in ways that could benefit pediatric cancer. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, small molecule drugs are exempt from Medicare price negotiations for only 9 years, compared with 13 years for biologics. This discrepancy could disincentivize the development of small molecule drugs in favor of biologics, an important consideration because small molecules are more accessible to patients than biologics (795)Makurvet FD (2021) Medicine in Drug Discovery, 9: 100075.. The EPIC Act would equalize this discrepancy, with both receiving 13 years of exclusion. This could lead to the development of more small molecule drugs and improve access to lifesaving medications for pediatric patients.

The impact of novel, transformative therapeutics for pediatric cancer would be greatly diminished without ensuring patients have widespread access to them. As such, many pieces of legislation are under consideration that can facilitate clinical care access for patients with pediatric cancer. For example, the Knock Out Cancer Act of 2025 calls for significant funding increases for NCI each year for the next 5 years—based on FY 2022 funding—to both address the dire need for increased research funding and to address the national crisis of cancer drug shortages (796)Congress.gov. H.R.3873 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): KO Cancer Act. Accessed: August 31, 2025..

Crucially, in addition to the inadequate availability of therapeutics, access to care for many patients is hindered by a lack of access to highly specialized providers. Treatments for children on Medicaid needing care outside their home state are often limited by restrictive provider screening and enrollment processes. Streamlining the process of accessing these experts is essential for timely and quality care. The Accelerating Kids’ Access to Care Act of 2025 would create a pathway for pediatric providers to enroll in multiple state Medicaid programs, reducing overall administrative burden, bureaucratic hurdles, and therefore delays in accessing specialized care for children with cancer (797)Congress.gov. H.R.1509 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): Accelerating Kids’ Access to Care Act of 2025. Accessed: August 31, 2025..

Furthermore, molecularly targeted therapeutics frequently require the use of companion diagnostics to select patients who are most likely to benefit from therapy. The Finn Sawyer Access to Cancer Testing Act would provide Medicare, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program coverage for cancer patients to receive molecular diagnostics during their cancer diagnosis (798)Congress.gov. H.R.1620 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): Finn Sawyer Access to Cancer Testing Act. Accessed: August 31, 2025.. It would also provide increased resources for genomic testing and genetic counseling. The bill is named after Finn Sawyer, who died from rhabdomyosarcoma before his fourth birthday following years of chemotherapy. The act would ensure that children with cancer, like Finn Sawyer, receive molecular testing at initial diagnosis and can benefit from lifesaving personalized treatments right away rather than waiting for when cancer recurs.

For the pediatric patient community, the cancer journey does not end once treatment is completed. Often, lifelong support is needed, given the significant health concerns experienced due to the potential long-term and late side effects of cancer treatment. The Comprehensive Cancer Survivorship Act (CCSA) would provide coverage for care-planning to address the transition from oncology to primary care, develop helpful patient navigation for survivorship services, establish employment assistance grants, increase education on survivorship needs, ensure coverage for fertility preservation services, and examine existing payment models and ways they can be improved (see Supporting Survivors of Pediatric Cancers). The CCSA aims to address known gaps in survivorship care for pediatric cancer patients and will also require additional research on the long-term and late effects of cancer diagnosis and treatment in these populations (799)National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. Comprehensive Cancer Survivorship Act (CCSA). Accessed: August 31, 2025..

Potential Policy Actions to Advance Pediatric Cancer Research and Care

While legislation currently under consideration has the potential to bring hope to the pediatric cancer community, additional opportunities exist that can catalyze further progress. Last reauthorized in January 2023, the STAR Act has been imperative to the expansion of pediatric cancer research funding, and lawmakers would be forward-thinking to reauthorize it again before the law expires at the conclusion of FY 2028. However, annual federal appropriations are still required to ensure funding for the STAR Act. Importantly, to achieve equitable outcomes for all children and adolescents with cancer, research to understand health disparities and the development of policies to address those disparities must be supported (800)Hunleth J, et al. (2024) EJC Paediatr Oncol, 4.. Policies that promote comprehensive insurance coverage for all populations, mitigate barriers to health care access, and incorporate social drivers of health would ensure access to high-quality cancer care and state-of-the-art treatments.

Additional policy opportunities can improve pediatric drug development. First, pediatric studies mandated by the RACE Act face the same issues around delays and noncompletion that are seen in overall pediatric research. Given the limited authority FDA has to address delays in study completion, policymakers could consider updating the RACE Act with new provisions that set timelines for initiating clinical trials and making pediatric data available. Second, FDA could reconsider how it determines whether a pediatric study is required under the RACE Act. The Pediatric Molecular Target List currently has more than 200 relevant targets, and more regular updates that adopt innovative, data-driven approaches to identify new molecular targets could increase the number of adult cancer drugs that go on to receive pediatric approval. Finally, FDA could consider ways to maximize the impact of pediatric cancer studies by streamlining the process to accept amendments to clinical trials, prioritizing enrollment based on anticipated level of benefit (especially for patients with molecular profiling data, where applicable), allowing trials that evaluate multiple therapies at once (see Figure 9), incentivizing combined trials in pediatric and adult populations when the target is present in both, and coordinating regulatory requirements and timelines with the European Medicines Agency and other international regulators to reduce duplication and conflicting requirements (801)Zettler ME (2022) Expert Rev Anticancer Ther, 22: 317..

Finally, policies that financially incentivize biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies to invest in therapies that specifically target pediatric cancer are critical. Over half of pediatric tumors are driven by genetic mutations not found in adult cancers (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers) (164)Ma X, et al. (2018) Nature, 555: 371.. Consequently, the current model of developing drugs for adult cancers and then studying them in pediatric patients will not lead to mutation-targeted therapies for a majority of childhood cancers. Instead, strategies must be employed to increase drug development that is specific to pediatric cancer targets.

Next Section: AACR Call to Action Previous Section: Understanding the Global Landscape of Pediatric Cancers