- Modernizing Clinical Research

- Advances in Pediatric Cancer Treatment With Surgery, Radiation, and Chemotherapy

- Less Is Sometimes More

- A New Era for Radiotherapy

- Evolving Chemotherapy Strategies

- Transforming Pediatric Cancer Outcomes Through Precision Diagnostics

- Advances in Pediatric Cancer Treatment With Molecularly Targeted Therapeutics

- Adding Precision to the Treatment of Leukemia

- New Hope for Patients With Lymphoma

- Personalizing the Treatment of Brain Tumors

- Expanding Treatment Options for Patients with Solid Tumors

- Advances in Biomarker-based Treatments

- Advances in Pediatric CancerTreatment With Immunotherapy

- Boosting the Cancer-killing Power of Immune Cells

- Releasing the Brakes on the Immune System

- Flagging Cancer Cells for Destruction by Immune System

- Redirecting T Cells to Attack Cancer Cells

- Critical Gaps in Pediatric Cancer Clinical Care

- Accelerating Advances in Pediatric Cancer Medicine

Progress in Pediatric Cancer Treatment

In this section, you will learn:

- Advances in the treatment of pediatric cancers are reflected in the greater than 85 percent 5-year relative survival rates for all cancers combined among children and adolescents. Despite the remarkable progress, cancer remains the leading cause of disease related death in children, and more than 60 percent of survivors experience significant long-term effects of treatment.

- The use of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy continues to evolve as more advanced forms of these treatments are developed and as better ways to apply them are discovered to improve survival and quality of life for pediatric cancer patients.

- With greater understanding of the biology of pediatric cancers, comes an increasing focus on utilizing personalized approaches to target cancers more precisely as well as on reducing treatment intensities among patients who have a favorable prognosis, to improve their quality of life.

- Molecular characterization of cancers and the use of targeted therapies, cellular therapies, and other immunotherapies have improved the care of certain pediatric cancers. However, progress still lags behind what has been achieved in adults, as most molecular drivers of pediatric cancers remain difficult to target and these tumors typically carry far fewer mutations, making them less responsive to immunotherapies.

- A new wave of pediatric cancer treatments is on the horizon, from innovative small molecules that target tumor-driving fusion proteins to next-generation CAR T-cell therapies designed to tackle brain cancer and other hard-to-treat solid tumors.

- Increased investments in pediatric cancer drug discovery and in global clinical trial collaborations are needed to accelerate the development of safer and more effective treatments for children and adolescents with cancer.

In the United States (US), an estimated 9,550 children (ages 0 to 14 years) and 5,140 adolescents (ages 15 to 19 years) will be diagnosed with cancer in 2025. Enormous progress has been made in the treatment of pediatric cancers over the past several decades, as reflected in the greater than 85 percent 5-year relative survival rates for all cancers combined. However, survival rates for children vary considerably depending on cancer type and patient age, among other factors, with some cancers, such as bone sarcomas and certain brain tumors, being difficult to treat and continuing to have poor survival.

Many of the initial advances in treating pediatric cancers were made through intensification of cytotoxic chemotherapeutics, which, while effective, were associated with significant toxicities, including short- and long-term adverse effects (267)Butler E, et al. (2021) CA Cancer J Clin, 71: 315.. With greater understanding of the biology of childhood and adolescent cancers and innovations in technology, has come an increasing focus on identifying therapeutic vulnerabilities and utilizing personalized approaches to target these diseases. Research has shown that cutting-edge technologies such as molecular profiling can improve the clinical care of children with cancer by informing personalized treatment options (268)Hodder A, et al. (2024) Nat Med: s41591.. In addition, efforts to reduce treatment intensities among patients with curable cancers who have a favorable prognosis have been equally impactful by improving their quality of life (269)Helms L, et al. (2023) Pediatrics, 152: e2023061539..

Modernizing Clinical Research

Clinical trials, a central part of the medical research cycle, ensure scientific discoveries ultimately reach the patients who need them the most as quickly and safely as possible. Before most new diagnostic, preventive, or therapeutic products can be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and used as part of patient care, their safety and efficacy must be rigorously tested through clinical trials. All clinical trials are reviewed and approved by institutional review boards before they can begin and are monitored throughout their duration. Federal funding is vital for pediatric cancer clinical research, as it provides the essential support needed to launch and sustain clinical trials that would otherwise not be possible, given the limited private sector investment because of the rarity and smaller patient populations of pediatric cancers compared to adult cancers (270)Neel DV, et al. (2020) Cancer Med, 9: 4495..

There are several types of cancer clinical trials, including treatment trials, prevention trials, screening trials, and supportive or palliative care trials, each designed to answer important research questions. In general, clinical studies in which participants are randomly assigned to receive an investigational treatment or the standard treatment (randomized clinical trials) are considered the most rigorous but can be challenging to conduct in rare diseases.

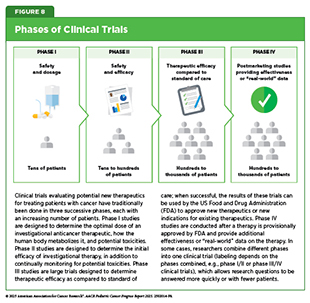

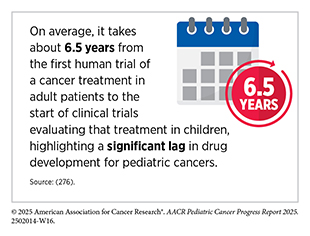

Cancer clinical trials have historically been conducted in three successive phases (see Figure 8). This approach has yielded numerous advances in patient care. However, the multiphase clinical testing process requires a large number of patients and takes many years to complete, making it extremely costly and one of the biggest barriers to rapid translation of scientific knowledge into clinical advances. Pediatric cancers are rare, with only about 15,000 cases annually in the United States, and some subtypes are diagnosed in fewer than 100 children each year. This limited patient population adds to the challenge of enrolling enough participants in pediatric cancer clinical trials in a timely manner. Studies evaluating overall survival as a primary endpoint can take more than one decade to complete, and by the time results are available, they may be outdated or inconclusive, delaying the development of new, effective treatments.

A higher proportion of childhood and adolescent patients with cancer, ranging from 20 percent to over 30 percent, depending on cancer type, participate in clinical trials in the United States, compared to approximately 7 percent of adult patients (9)Lupo PJ, et al. (2025) J Natl Cancer Inst.(271)Unger JM, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 2139.. Enrollment of pediatric patients from racial and ethnic minority groups is also higher than that of adult patients (272)Fashoyin-Aje LA, et al. (2024) JAMA Oncol, 10: 380.(273)Faulk KE, et al. (2020) PLoS One, 15: e0230824.. However, a lack of diversity still exists among clinical trial participants (274)Wyatt KD, et al. (2024) JCO Oncol Pract, 20: 603.. For example, a retrospective analysis of clinical trial participation among children and adolescents with blood cancer showed that Black patients were 60 percent less likely than White patients to enroll in a trial (275)Monroe C, et al. (2025) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 72: e31641..

Conducting pediatric cancer clinical trials globally can potentially help speed up drug development and approval by increasing the pool of eligible patients. This broader participation may allow trials to enroll faster, gather more diverse data, and generate results sooner, ultimately accelerating the availability of new treatments for children worldwide. Expanding global access to cancer clinical trials must become a strategic priority for all stakeholders committed to accelerating breakthroughs in pediatric cancer care (see Global State of Pediatric Cancer Clinical Trials).

US lawmakers and FDA have also been working on legislation and guidelines intended to increase the diversity of clinical trial participants. FDA has taken actions to improve the availability of anticancer therapeutics for pediatric patients. In 2020, the agency provided guidance that included recommendations regarding the inclusion of children and adolescents, when appropriate, in clinical studies, and initiated enforcement of key provisions in the Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity (RACE) for Children Act requiring certain targeted cancer therapies developed for adult patients to be studied in pediatric patients (see Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research and Patient Care Through Evidence-Based Policies).

Research-driven advances in our understanding of cancer biology, in particular the genetic mutations that underpin cancer initiation and growth (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers), are enabling researchers and regulators to develop new ways of designing and conducting pediatric cancer clinical trials, including the emergence of adaptive and seamless clinical trial designs (277)Forrest SJ, et al. (2018) Curr Opin Pediatr, 30: 17.. These new approaches aim to streamline clinical trials of new anticancer therapeutics by using biomarkers—molecular features that help identify which patients are most likely to benefit—to match the right treatments with the right patients earlier in the process. Such strategies can reduce the number of patients who need to be enrolled in clinical trials; combine separate phases of trials into a single, continuous study; and decrease the length of time it takes for a new anticancer therapeutic to be tested and made available to patients.

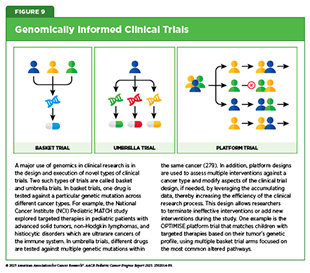

In some clinical trials, cancer-driving genomic alterations, rather than the anatomic site of diagnosis of the original cancer, are being used to identify patients most likely to benefit from an investigational anticancer therapeutic (see Figure 9). If successful, these clinical trials, which are called “basket” trials, have the potential to lead to FDA approvals that are agnostic of the site of cancer origin. One example of a basket trial is the NCI Pediatric MATCH study that was launched in 2017 (see Integrating Molecular Insights Into Clinical Care). The trial aimed to systematically test therapeutics that target specific genetic changes in children, adolescents, and young adults (AYAs) between 1 and 21 years old who are diagnosed with advanced cancers that have gotten worse while on treatment or have relapsed after treatment. Results from the study indicated that about one-third of patients who had their tumors tested had targetable genetic changes, highlighting the potential of precision medicine in pediatric cancer care (163)Parsons DW, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 2224.. Another genomics-informed clinical trial that yielded promising results involved the testing of a molecularly targeted therapeutic called larotrectinib in adult and pediatric patients who have any type of cancer characterized by the presence of genetic alterations called TRK fusions (see Advances in Biomarker-based Treatments) (278)Drilon A, et al. (2018) N Engl J Med, 378: 731..

Future progress in pediatric cancer treatment necessitates further embracing innovative, biologically driven research frameworks. Designing biologically driven protocols and utilizing collaborative global networks may address the unique challenges in childhood cancer, such as small patient populations and diverse cancer subtypes (280)Khan T, et al. (2019) Ther Innov Regul Sci, 53: 270.. According to an encouraging recent report, pediatric cancer trials over the past 20 years have shifted toward more efficient designs, greater use of biomarkers, and combination therapies, reflecting advances in understanding the molecular complexity of cancer and evolving regulatory needs (see Applying Regulatory Science to Advance Pediatric Cancer Research and Care) (281)Bautista F, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 2516..

As trial designs evolve, it will be equally important to integrate patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to ensure that children’s own experiences and quality of life are central to evaluating new therapies. Incorporating PROs into pediatric cancer clinical trials is critical for capturing the full impact of treatment beyond traditional clinical measures (282)Greenzang KA, et al. (2025) JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute.(283)Riedl D, et al. (2024) EJC Paediatric Oncology, 4.. Direct reports from children and adolescents about their symptoms, side effects, and quality of life offer unique insights that may be missed by physician assessments or laboratory tests (see Care Coordination Across the Pediatric Cancer Survivorship Continuum). Recent work highlights validated, age-appropriate tools as well as the growing role of electronic PROs, which allow for timely and efficient symptom monitoring. Embedding these measures in trial design not only elevates the patient’s voice but also supports more responsive, patient-centered care, ultimately leading to therapies that improve both survival and quality of life.

Harnessing emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning may further improve clinical research by helping to identify patients eligible for trials, predicting which patients are most likely to benefit from experimental treatments, simulating how new therapeutics work, and creating virtual patient cohorts using past data and assessing how well trial results apply to real-world patient populations (252)Hassan M, et al. (2025) Cancers (Basel), 17.(284)Foote HP, et al. (2024) J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther, 29: 336.. However, current limitations of AI, including a lack of data diversity, standardized benchmarks, and proper regulatory oversight, must be overcome before these tools can become part of regular clinical practice.

Advances in Pediatric Cancer Treatment With Surgery, Radiation, and Chemotherapy

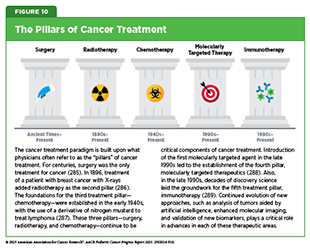

Surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are the three long-standing pillars of cancer treatment and continue to be the mainstays of clinical care for most pediatric patients. However, in the past two decades, we have witnessed the emergence of two new pillars of cancer care—molecularly targeted therapy and immunotherapy, including cellular therapy (see Figure 10). The therapeutics that form these pillars of cancer care can be remarkably effective and often less toxic than radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, only a minority of pediatric patients with cancer are treated with molecularly targeted therapy or immunotherapy. Often this is because there are no effective molecularly targeted therapeutic or immunotherapeutic approaches available. It may also be that surgery, radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy result in excellent outcomes.

Importantly, the use of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy is constantly evolving as we develop new forms of these treatments and identify new ways to use existing treatments to improve survival and quality of life for children and adolescents. Additionally, even though surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are mainstays of cancer treatment, they can have long-term adverse effects, which are particularly debilitating for pediatric patients (see Supporting Survivors of Pediatric Cancers). For example, while chemotherapy has transformed outcomes for many children with cancer, recent studies have found that these treatments can also leave lasting marks on healthy tissues. By studying children who developed a second primary cancer, researchers showed that chemotherapy, especially platinum-based drugs, can accelerate DNA damage far beyond what happens through natural aging, helping to explain how some second cancers arise (290)Sánchez-Guixé M, et al. (2024) Cancer Discovery, 14: 953.. These findings have led many researchers to investigate whether less aggressive treatment can allow some patients the chance of an improved quality of life without an adverse effect on long-term survival. In the past decade, a deeper understanding of pediatric cancer biology has driven the implementation of risk stratification and treatment de-escalation approaches in the clinic (see Molecular Insights Driving Risk Stratification and Treatment).

Less Is Sometimes More

Long-term effects of radiation therapy can negatively impact a child’s quality of life. Researchers continue to evaluate approaches to making radiotherapy safer and more effective, including the use of biomarkers to identify patients who are unlikely to benefit from radiation or those who may be more vulnerable to its toxic effects, allowing radiotherapy to be reduced or even avoided without affecting patient outcomes.

For example, a number of studies have now demonstrated that in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), irradiation of the brain to prevent relapses is likely unnecessary in most cases (291)Jeha S, et al. (2019) J Clin Oncol, 37: 3377.(292)Pui CH, et al. (2009) N Engl J Med, 360: 2730.. Instead, researchers found that administering chemotherapy into the spinal fluid lowered the risk of ALL relapses in the brain and spinal cord with reduced side effects, compared to irradiation. These findings are vital, considering that brain irradiation in children, especially young children, can cause devastating health problems, including a higher chance of developing a second primary cancer in the brain, difficulties with memory and thinking, hormone problems, and dementia later in life.

A major clinical trial found that some patients with Wilms tumor, the most common type of kidney cancer in children, can safely skip radiation therapy, helping to reduce its long-term adverse effects (293)Dix DB, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 1564.. Traditionally, the treatment for patients with stage IV Wilms tumors that have spread to the lungs has been chemotherapy and surgery, followed by radiation therapy to the lungs. Data from the trial suggest that nearly half of children with advanced Wilms tumor can avoid lung radiation therapy if they respond well to initial chemotherapy (293)Dix DB, et al. (2018) J Clin Oncol, 36: 1564.. Children whose lung nodules disappeared after 6 weeks of standard chemotherapy and continued treatment without radiation had a 4-year survival rate of over 96 percent, which was similar to the survival in those who received radiation. Omission of radiation can reduce serious long-term side effects, such as heart and lung damage or second primary cancers (see Supporting Survivors of Pediatric Cancers).

Another example of reducing treatment intensity comes from children with intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma. Researchers have shown that children with intermediate-risk Hodgkin lymphoma who receive intense chemotherapy, and those whose disease responds quickly, could skip radiation without affecting remission rates (294)Friedman DL, et al. (2014) J Clin Oncol, 32: 3651.. Similar results were seen in another large study conducted in Europe, in which researchers evaluated a more precise approach to treating intermediate and advanced pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma (295)Mauz-Körholz C, et al. (2022) Lancet Oncol, 23: 125.. All children in the study received two cycles of chemotherapy, after which their response was assessed with imaging. Those whose cancer had responded well did not receive radiotherapy and still had excellent outcomes, similar to those who received radiotherapy. These data demonstrate that radiotherapy can be eliminated for these patients and underscore the power of tailoring treatment based on early responses, thus helping to minimize long-term side effects without compromising effectiveness.

In another study, researchers evaluated whether two cycles of chemotherapy could be just as effective as the usual four, while also reducing the harmful side effects in children who had a rare liver cancer called hepatoblastoma, and whose tumors could be completely removed by surgery (297)Katzenstein HM, et al. (2019) Lancet Oncol, 20: 719.. The phase III trial demonstrated that giving less chemotherapy after surgery led to equally excellent outcomes: Over 90 percent of children remained free from cancer recurrence, and 95 percent were alive after 5 years, with far fewer side effects like hearing loss.

This finding supports a broader goal of ensuring children have the highest chance of cure that restores them to full health and well-being. Importantly, the reduced-chemotherapy approach is currently being tested in a much larger international clinical trial so that physicians worldwide can confirm these data.

Researchers are also evaluating the optimal sequence of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy to maximize benefits for patients. As an example, a study aimed to assess the best strategy for the use of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery in patients with embryonal sarcoma of the liver (ESL), a rare and aggressive liver cancer that primarily affects children and young adults (298)Spunt SL, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 2683.. The findings demonstrated that even though most patients with ESL are diagnosed with advanced disease, treatment with several cycles of chemotherapy followed by a complete tumor removal can lead to good outcomes, reduce surgical risks, and sometimes avoid the need for radiotherapy altogether.

To lower the adverse effects and morbidity associated with surgery, minimally invasive procedures—driven by technological advances and surgeon expertise—are being used more often in pediatric cancer care (299)Wijnen MWH, et al. (2021) Surg Oncol Clin N Am, 30: 417.(300)Phelps HM, et al. (2018) Children (Basel), 5.. Less invasive surgeries can offer benefits, such as smaller incisions and improved precision, though their appropriate use in pediatric cancer still needs to be defined through randomized clinical trials to ensure treatment standards and optimal outcomes are upheld.

A New Era for Radiotherapy

Over the past few decades, childhood cancer survival rates have greatly improved, but long-term side effects from treatment remain a concern. Radiation therapy, while vital for treating certain childhood cancers, can cause significant long-term problems. Research has focused on reducing or even eliminating radiation in children who respond very well to chemotherapy, as seen in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, certain Wilms tumors with lung metastasis, intracranial germinoma, and pediatric nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In medulloblastoma, the most common malignant brain tumor in children, genetic testing can identify subgroups of patients for whom lower doses of radiation are being studied to limit long-term harm (301)Upadhyay R, et al. (2024) Cancers (Basel), 16..

At the same time, new strategies such as stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy, which can precisely deliver radiation to tumors, are being explored for children with limited metastasis, to deliver very high, precise doses over fewer sessions (see Sidebar 12). This approach can help control tumors in difficult-to-treat cancers like rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma (302)Casey DL, et al. (2025) Practical Radiation Oncology, 15: 180.. Advances in modern radiation techniques, including proton therapy and highly targeted photon therapy, are also allowing health care providers to spare more healthy tissue and reduce long-term side effects, making it possible to tailor radiation more safely and effectively to the needs of each child.

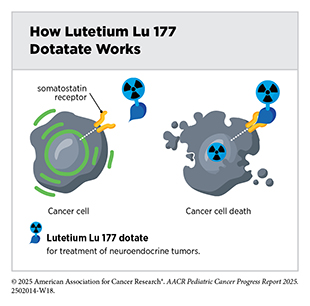

One of the most exciting and fastest-growing areas in radiotherapy is the use of radiopharmaceuticals or molecularly targeted radiotherapeutics—radiation-emitting molecules that are linked to targeting molecules, which steer the radiation specifically to cancer cells. A particularly promising innovation is theranostics, which combines diagnostic imaging and molecularly targeted radiotherapy to deliver personalized treatment based on a patient’s unique tumor characteristics. A few such diagnostic therapeutic pairs have already been approved by FDA in recent years for adult patients and many more are at various stages of preclinical and clinical testing.

In April 2024, FDA approved the molecularly targeted radiotherapeutic lutetium Lu 177 dotatate (Lutathera) for children age 12 and older with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors that express proteins known as somatostatin receptors, including tumors originating in the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. This was the first FDA approval of a radiopharmaceutical for this condition in children. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are extremely rare in children and have few available treatment options, highlighting the importance of this approval.

Evolving Chemotherapy Strategies

As with surgery and radiotherapy, chemotherapy is more commonly used to treat cancer in combination with one or more additional types of treatments. Newer and more effective chemotherapeutics continue to be evaluated in clinical research. In addition, researchers are investigating optimal dosage, novel formulations, treatment combinations, and optimal timing of chemotherapy delivery to improve patient outcomes. For example, the chemotherapeutic nelarabine was first approved in 2005 for children whose T-cell leukemia had come back or had not responded to treatment, but it is now part of the initial treatment after studies showed it helps more children survive when added to standard initial chemotherapy (303)Dunsmore KP, et al. (2020) J Clin Oncol, 38: 3282.. T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is less common than the B-cell form of the disease but historically it had been more difficult to treat requiring more intensive chemotherapy regimens.

Transforming Pediatric Cancer Outcomes Through Precision Diagnostics

Remarkable advances in our understanding of cancer biology, including the discovery of numerous cellular and molecular alterations that drive tumor growth, have ushered in a new era of precision medicine. As a result, the standard of care is shifting away from a one-size-fits-all approach toward treatments tailored to the patient and the unique characteristics of their cancer. Therapeutics directed to molecules that influence cancer cell multiplication and survival target tumor cells more precisely, thereby limiting damage to healthy tissues, compared to chemotherapeutics, which generally target all rapidly dividing cells. As a result, molecularly targeted therapies are not only saving lives but also enabling patients with cancer to have a higher quality of life.

Unfortunately, our understanding of pediatric cancer biology does not consistently match the depth of knowledge we have for common adult cancers, largely due to the rarity of these diseases and historical gaps in research investment. In addition, the known molecular drivers in pediatric cancers often make for difficult drug targets. As a result, progress in implementing precision medicine approaches to pediatric cancers has not kept pace with advances seen in adult cancers. Despite these challenges, considerable progress has been made in recent years. Large-scale tumor profiling, genomic sequencing, epigenetic characterization, and collaborative research initiatives from the United States and around the globe have already identified actionable targets in some pediatric cancers, leading to changes in treatment for selected patients (see Integrating Molecular Insights Into Clinical Care and Sidebar 13). In many others, the molecular drivers have been identified but they are not yet pharmacologically actionable. Ongoing studies continue to expand our understanding, offering hope that precision medicine will increasingly benefit more children with cancer.

In the United States, the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (CCDI), launched in 2019, is a national effort to collect information from every child, adolescent, and young adult diagnosed with cancer, no matter where they receive care. The goal of CCDI is to use clinical and genetic data to speed diagnosis, guide treatment, and improve prevention, quality of life, and long-term outcomes for all pediatric cancers (see Policies Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research and Care). Building on this, the Molecular Characterization Initiative (MCI), launched in 2022, and Children’s Oncology Group’s Project:EveryChild, provide advanced molecular testing at diagnosis, helping health care providers and families choose the most effective treatment while linking clinical care and research to further accelerate discoveries (see Shared Data and Collaborations Advancing Pediatric Cancer Research) (309)Flores-Toro JA, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 4045..

As of July 2025, MCI has analyzed samples from over 6,000 children and adolescents, encompassing a wide range of cancers, most of them solid tumors (32)Flores-Toro J, et al. (2025) J Natl Cancer Inst.. Most cases are central nervous system (CNS) tumors, followed by soft tissue sarcomas, rare tumors, neuroblastomas, and Ewing sarcomas. Molecular testing helped refine the diagnosis for about one-third of participating children with cancer. Although MCI is ongoing, early indications are that this complex clinical testing led to 15 percent of those tested receiving treatments targeting specific molecular changes, and 8.5 percent being enrolled in clinical trials based on their test results, demonstrating how comprehensive molecular profiling can directly guide care and improve access to cutting-edge therapies. Additionally, the analysis revealed that about 14 percent of patients carried inherited or de novo mutations linked to cancer (see Genetic Alterations), which may guide clinical care for their family members.

European precision oncology studies—MAPPYACTS, which demonstrated the real-world feasibility and impact of tumor molecular profiling in relapsed pediatric cancers, and AcSé-ESMART, a proof-of-concept platform trial aimed at genetically matching childhood cancer patients to targeted therapies under a single adaptive protocol—together underline some of the global efforts in generating molecularly driven treatment strategies for childhood cancer (see Molecular Profiling Driving Precision Medicine) (310)Berlanga P, et al. (2022) Cancer Discov, 12: 1266.(311)Geoerger B, et al. (2024) Eur J Cancer, 208: 114201..

Molecular Insights Driving Risk Stratification and Treatment

Advances in molecular profiling of childhood cancers have significantly improved clinical care. By identifying genetic features that help predict how likely it is for a child’s cancer to return, health care providers can tailor the modality or intensity of treatment to each patient’s specific needs.

For example, by analyzing the molecular features of B-cell ALL (B-ALL) cells, clinicians can more accurately assess each patient’s risk of relapse and tailor therapy accordingly (312)Inaba H, et al. (2020) Haematologica, 105: 2524.. Research has indicated that children with genetic alterations such as the ETV6::RUNX1 fusion or hyperdiploidy, a condition in which leukemia cells have more chromosomes than normal, tend to have favorable outcomes and may be treated with less intensive chemotherapy to help reduce long-term side effects. In contrast, children with high-risk alterations such as BCR::ABL1 fusion or KMT2A gene rearrangements often require more intensive chemotherapy or targeted treatment approaches. Moreover, recent studies show that even within favorable or high-risk subtypes, additional genetic changes, such as alterations in IKZF1 or CREBBP, or certain chromosomal gains and losses, can further influence the chance of relapse (313)Chang TC, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 3491..

Although T-ALL is much less common than B-ALL in children, it is often more aggressive. In a recent study, scientists analyzed genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data from over 1,300 uniformly treated pediatric patients and uncovered 15 distinct subtypes of T-ALL (100)Polonen P, et al. (2024) Nature, 632: 1082.. Each subtype was shown to have distinct molecular characteristics linked to how aggressive the cancer was and how patients responded to treatment. These discoveries could lead to more precise diagnosis, better ways to predict outcomes, and ultimately more personalized therapies tailored to each child’s cancer.

Comprehensive molecular testing has become indispensable for accurately diagnosing, grading, and predicting outcomes in CNS tumors for which these tests are no longer optional, but the standard diagnostic criteria as established by the World Health Organization (WHO) (314)Horbinski C, et al. (2025) JAMA Oncol, 11: 317.. In fact, many CNS tumor types cannot be reliably diagnosed under the current WHO criteria without molecular data, which means that routine molecular profiling is now fundamental for correct patient classification and subsequent treatment planning. Despite cost concerns, these tests account for less than 5 percent of the average overall cost of treating CNS tumors but still deliver major benefits in patient management, including more precise prognoses, better therapeutic matching, and clearer clinical trial eligibility.

One CNS tumor in which molecular classification is driving diagnosis and clinical care is medulloblastoma. Advances in genetic testing now allow clinicians to classify patients with medulloblastoma based on their underlying biological drivers into four distinct subgroups. Referred to as WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 medulloblastoma, these subtypes differ in how aggressive they are and how likely they are to respond to treatment. These subtypes can be further divided based on epigenetic patterns that help predict how the cancer will behave (315)Northcott PA, et al. (2017) Nature, 547: 311.. Research has identified that children in the WNT subgroup have an excellent prognosis. Studies are evaluating whether radiation and chemotherapy doses can be safely reduced among these patients to limit long-term side effects, with early results showing prolonged survival and fewer complications (301)Upadhyay R, et al. (2024) Cancers (Basel), 16.. At the same time, researchers are identifying high-risk subgroups, such as patients within Group 3 or Group 4 with certain mutations, that are resistant to treatments (316) Neuro-Oncology., and exploring stronger, targeted approaches to improve outcomes.

In neuroblastoma, the most common pediatric solid tumor outside the CNS, rigorous molecular and clinical risk stratification (using age, stage, spread, and specific genetic and chromosomal aberrations) has enabled reduction of therapy intensity in low-risk cases while enabling intensified multi-modal treatment for high-risk patients, resulting in significantly improved cure rates (317)Bagatell R, et al. (2023) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 70 Suppl 6: e30572..

Molecular profiling has also allowed researchers to precisely monitor minimal residual disease (MRD), which occurs when a very small number of cancer cells remain in the body during or after treatment, helping clinicians adjust therapy in real time based on how well the cancer is responding. This approach is significantly improving outcomes while minimizing unnecessary toxicity, marking a major advance in the personalized treatment of pediatric cancers. For example, a large international study found that combining MRD status with genetic alterations enables more refined risk classification in pediatric ALL, allowing low-risk patients to receive less intensive therapy to reduce long-term side effects, while directing more intensive treatment to high-risk patients, thereby improving overall outcomes (318)Moorman AV, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 4228..

Recent research is demonstrating the growing promise of liquid biopsies in MRD testing (see Liquid Biopsy). These innovative techniques allow doctors to detect small amounts of cancer DNA in bodily fluids such as blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), offering a less invasive way to monitor disease, guide treatment, and predict outcomes. As one example, in children with solid tumors, including sarcomas and neuroblastoma, liquid biopsies along with innovative new technologies to analyze DNA and RNA have made it possible to detect gene fusions, a common driver in many childhood cancers, directly from blood samples and help track how tumors respond to treatment and identify early signs of recurrence (319)Christodoulou E, et al. (2023) npj Precision Oncology, 7: 21.. In children and adolescents with newly diagnosed Ewing sarcoma or osteosarcoma, circulating tumor DNA in the blood was linked to a significantly poorer outcome (320)Shulman DS, et al. (2018) British Journal of Cancer, 119: 615..

In childhood brain tumors, including medulloblastoma and diffuse midline glioma, researchers have demonstrated that analyzing tumor DNA in CSF can provide critical insights into whether cancer remains after surgery or how tumors respond to radiotherapy (157)Liu APY, et al. (2021) Cancer Cell, 39: 1519.(321)Panditharatna E, et al. (2018) Clin Cancer Res, 24: 5850.. Another study was able to correlate genetic alterations in circulating tumor DNA to MRD levels in nearly every child with leukemia, showing how liquid biopsies could provide a powerful new tool for monitoring childhood cancers (154)Lei S, et al. (2025) Leukemia, 39: 420.. Liquid biopsy and MRD tools have immense potential in pediatric oncology, offering safer and more precise ways to track disease, personalize therapy, and ultimately improve outcomes for children with cancer.

Advances in Pediatric Cancer Treatment With Molecularly Targeted Therapeutics

Remarkable advances in our understanding of the biology of cancer, including the identification of numerous cellular and molecular alterations that fuel tumor growth, have set the stage for a new era of precision medicine (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers). Molecularly targeted cancer treatments, which form the foundation of precision medicine, work by homing in on the molecules such as mutated proteins that drive a tumor’s growth, which makes them more precise and often less toxic than traditional chemotherapy that indiscriminately attacks both cancerous and rapidly dividing healthy cells. As a result, these treatments are saving and improving the lives of some children with cancer. However, progress in developing such targeted therapies for pediatric cancers has been limited. Many of the key genetic drivers in childhood cancers such as MYC and MYCN (in medulloblastoma and neuroblastoma), PAX fusions (in rhabdomyosarcoma), and EWSR1 fusions (in Ewing sarcoma) have long been considered undruggable. Emerging therapeutic approaches, including targeted protein degradation, RNA-based, and epigenetic strategies, are beginning to offer new ways to tackle these challenging targets and may ultimately expand the benefits of precision medicine to more children with cancer.

Since 2015, FDA has approved and expanded the use of many molecularly targeted therapeutics for treating children with cancers (see Table 4). However, these numbers remain far short of the approvals seen in adult cancers, and very few of these drugs have been developed specifically for pediatric patients. For instance, between 1997 and 2017, just six out of 117 FDA approved cancer therapeutics had an initial approval that included children (267)Butler E, et al. (2021) CA Cancer J Clin, 71: 315.. The following sections highlight the molecularly targeted therapies that have been approved by FDA for pediatric cancers over the past 10 years.

Adding Precision to the Treatment of Leukemia

Leukemias are the most common cancer among US children and adolescents. Among children ages 0 to 14, ALL is the most common cancer diagnosis. The 5-year survival for children and adolescents is greater than 90 percent, attributable to spectacular advances in risk stratification at diagnosis, with treatment escalation for those with high risk of relapse as well as to the new and improved treatment options that are now available in the clinic. Decades of basic, translational, and clinical research have enhanced our knowledge of the underpinnings of leukemia as well as knowledge of the immune system. Researchers are harnessing this knowledge to develop personalized treatments including molecularly targeted therapeutics and immunotherapeutics that target ALL.

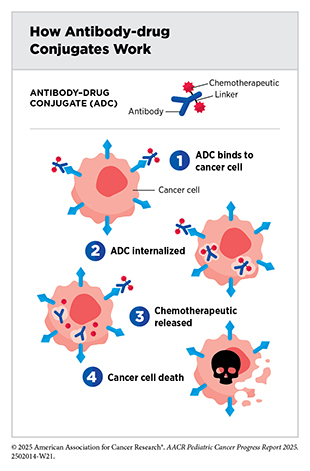

Antibody–drug conjugates are an emerging class of molecularly targeted therapeutics that use an antibody to deliver an attached cytotoxic chemotherapeutic directly to the cancer cells that have the antibody’s target on their surfaces. Once the antibody attaches to its target on the surface of a cancer cell, the antibody–drug conjugate is internalized by the cells. This leads to the chemotherapeutic being released from the antibody and killing the cancer cell. The precision of antibody targeting reduces the side effects of the chemotherapeutic compared with traditional systemic delivery.

In most children, ALL arises in immune cells called B cells, which have a protein called CD22 on the surface. Inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) is an antibody–drug conjugate comprising a CD22-targeted antibody linked to the chemotherapeutic calicheamicin. It was approved for treating adults with B-ALL in August 2017. Subsequent studies have shown that inotuzumab ozogamicin is also effective in children and adolescents. In March 2024, FDA approved the therapeutic for pediatric patients 1 year and older with CD22-positive B-ALL that has relapsed or stopped responding to standard treatments. The approval was based on findings from a clinical trial in which about 40 percent of patients who received inotuzumab ozogamicin achieved a complete remission, which means they had no evidence of cancer (323)O’Brien MM, et al. (2022) J Clin Oncol, 40: 956..

Patients who receive inotuzumab ozogamicin may need a stem cell transplant to ensure durable cancer remission. While treatment with inotuzumab ozogamicin increases the risk of developing serious liver toxicities in certain patients, its approval has increased treatment options for a group of ALL patients who may be ineligible for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy (see Boosting the Cancer-killing Power of Immune Cells) and have no remaining options.

Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) ALL is a rare but aggressive form of ALL in children caused by a genetic mutation that leads to the formation of the BCR::ABL fusion gene, the same structural variation (see Sidebar 4) that drives most cases of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a slow-growing blood cancer. Decades of research led to the discovery of the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene that produces an abnormal BCR::ABL protein which drives uncontrolled growth of CML cells. These findings spurred the development and FDA approval of molecularly targeted therapeutics, such as imatinib and dasatinib, which specifically block BCR-ABL protein function, and have transformed the treatment of CML.

Based on positive data from clinical trials, imatinib and dasatinib have since received expanded approval by FDA for treatment of children with Ph+ ALL and are significantly improving outcomes for patients (324)Cerchione C, et al. (2021) Front Oncol, 11: 632231.(325)Murphy L, et al. (2023) Lancet Haematol, 10: e479.. When used in combination with chemotherapy, these treatments have reduced the need for more aggressive therapy like stem cell transplantation and have led to better survival rates for pediatric patients.

CML is rare in children, accounting for only 2 percent to 3 percent of leukemias diagnosed in those under 15 years old, and about 9 percent of cases among adolescents ages 15 to 19 (326)Athale U, et al. (2019) Pediatr Blood Cancer, 66: e27827.. BCR::ABL targeted therapeutics such as dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib, which are approved for adult patients, have also been approved by FDA for pediatric patients with CML driven by the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene. However, because these drugs also interfere with pathways important for growth, metabolism, and hormone function, their long-term effects in children, who are still developing, remain unclear. As newer and safer treatments are explored, defining the safety and effectiveness of existing therapies in pediatric patients is critical.

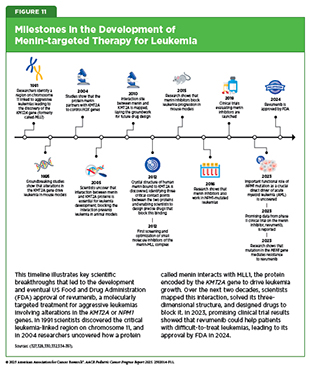

Structural variations, also known as rearrangements, in the KMT2A gene are observed in up to 80 percent of infant ALL and in 5 percent to 15 percent of children and adults with acute leukemia, including those that originate in myeloid or lymphoid cells, or a mix of both (327)Issa GC, et al. (2023) Nature, 615: 920.. The KMT2A gene encodes a protein called MLL1, which plays a critical role in normal blood cell development by regulating gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms.

KMT2A rearrangements disrupt normal cell development by causing blood cells to revert to an immature state, preventing them from forming functional blood cells. The result is the formation of leukemia cells instead of mature blood cells. This disruptive process is driven by the interaction of MLL1 with another protein called menin (328)Yokoyama A, et al. (2005) Cell, 123: 207.. Together, menin and MLL1 form a complex that binds to DNA in the cell’s nucleus and triggers harmful genetic programs that lead to leukemia. Acute leukemia with KMT2A rearrangements is associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis (329)Issa GC, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol, 43: 75.. In addition to KMT2A rearrangements, mutations in the NPM1 gene—detected in up to 30 percent of adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cases—also depend on menin to promote leukemia development (330)Kuhn MW, et al. (2016) Cancer Discov, 6: 1166.(331)Issa GC, et al. (2021) Leukemia, 35: 2482..

These discoveries led to the development of menin-targeted therapies (see Figure 11) (332)Borkin D, et al. (2015) Cancer Cell, 27: 589.(333)Garber K (2024) Nat Rev Drug Discov, 23: 567., culminating in the November 2024 FDA approval of revumenib (Revuforj), the first menin inhibitor, for adult and pediatric patients (1 year and older) with acute leukemia harboring KMT2A rearrangements who never responded to or experienced relapse after initial treatments. Revumenib works by blocking the interaction between menin and MLL1. By binding to menin, it prevents the menin–MLL1 complex from attaching to DNA, thereby halting the abnormal genetic programs that fuel leukemia. As a result, leukemia cells are either driven to mature into healthy blood cells or are eliminated.

FDA approval of revumenib was based on a phase I/II clinical trial in which more than 21 percent of patients experienced complete remission (cancer no longer detectable in the bone marrow, and the number of healthy blood cells returned to normal levels) or complete remission with partial recovery of their blood counts (cancer is no longer detectable in the bone marrow, with partial recovery of the number of healthy blood cells). The benefits lasted a median of over 6 months. Revumenib has provided patients such as Tyler Peryea with a personalized treatment option that is much less aggressive than traditional chemotherapeutics.

Ongoing studies are looking to identify mechanisms of resistance to revumenib treatment and evaluating revumenib as the initial treatment as well as in combination with other molecularly targeted therapeutics or chemotherapeutics to improve outcomes for more patients.

AML is the second most common leukemia in children, accounting for 25 percent of childhood leukemia cases. Traditionally, most children were treated with chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplants (267)Butler E, et al. (2021) CA Cancer J Clin, 71: 315.. Molecularly targeted therapeutics, such as revumenib and others, are now becoming the standard treatment for many children. As one example, in September 2017, FDA approved gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) for the treatment of adults and pediatric patients 2 years and older whose AML has relapsed or has stopped responding to other treatments and whose leukemia cells have the protein CD33.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin is an antibody–drug conjugate comprising the chemotherapeutic calicheamicin attached to a CD33-targeted antibody. In most patients, AML cells have the molecule CD33 on the surface, and FDA approval was specifically for this precisely defined patient population. The approval was based on clinical trials that indicated adding gemtuzumab ozogamicin to standard chemotherapy lowered the chance of relapse and improved outcomes for children and adolescents with AML, especially for those whose cancer cells had high levels of the protein CD33 (352)Pollard JA, et al. (2016) J Clin Oncol, 34: 747.(353)Gamis AS, et al. (2014) J Clin Oncol, 32: 3021..

In June 2020, FDA expanded the use of gemtuzumab ozogamicin for children 1 month and older with newly diagnosed CD33-positive AML based on findings from a large clinical trial that showed that adding gemtuzumab ozogamicin to standard chemotherapy helped more children stay in remission without the cancer returning (354)US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves gemtuzumab ozogamicin for CD33-positive AML in pediatric patients. Accessed: September 30, 2025..

New Hope for Patients With Lymphoma

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) is a blood cancer that accounts for approximately 6 percent of all childhood cancers. The disease is most common in adolescents. Historically, pediatric cHL has been treated with intensive chemotherapy combinations. While these treatments have been successful in curing many patients, they carry long-term risks, including damage to the heart and lungs or the risk of second primary cancer later in life.

In a significant advance, in November 2022, FDA approved the antibody conjugate brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) for the treatment of children ages 2 and older with untreated cHL who are more likely to experience relapse or be resistant to treatment. This was the first approval of the therapeutic for pediatric patients, being already used in adults. Brentuximab vedotin delivers a cytotoxic chemotherapeutic known as monomethyl auristatin E directly to cancer cells expressing a protein called CD30, which is found on the surface of Hodgkin lymphoma cells. This targeted approach aims to kill cancer cells more precisely, potentially reducing side effects.

The approval was based on results from a phase III clinical trial in which children and adolescents treated with brentuximab vedotin in combination with chemotherapy were 59 percent less likely to experience relapse, disease progression, or death compared to those receiving standard chemotherapy (355)Castellino SM, et al. (2022) N Engl J Med, 387: 1649.. This approval marks a major step toward safer, more effective, and potentially less toxic treatment for children with high-risk HL. More than half of the children in both treatment groups received carefully tailored, lower-dose radiation after chemotherapy because their tumors were slow to shrink as evidenced from interim positron emission tomography (PET) scans. This approach highlights how response-based imaging can guide radiotherapy and help reduce side effects of radiation and preserve long-term health while still achieving high cure rates.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a group of blood cancers that originate from different kinds of immune cells such as B cells, T cells, or natural killer cells. Common NHLs in children include Burkitt lymphoma (BL), lymphoblastic lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Of these, ALCL is a rare but fast-growing cancer that originates from T cells and makes up 10 percent to 15 percent of pediatric NHL cases.

Research has demonstrated that 90 percent of children with ALCL have alterations in the ALK gene. A key therapeutic advance in treating ALCL in children was the expanded use of the ALK-targeted therapeutic crizotinib (Xalkori)—originally approved in 2011 to treat certain patients with lung cancer—for treatment of children and adolescents who have experienced relapse or who have refractory ALCL expressing aberrant forms of the ALK gene. The approval of crizotinib to treat ALK-positive ALCL was based on findings from a phase II clinical trial. Eighty-one percent of patients who participated in the trial no longer showed any signs of cancer. Of the patients who responded to the treatment, 39 percent maintained a response for at least 6 months, and 22 percent maintained a response for at least a year following treatment (478). Researchers are now evaluating whether crizotinib in combination with chemotherapy could be used as the initial treatment for children with newly diagnosed ALCL (356)Lowe EJ, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 2043..

Personalizing the Treatment of Brain Tumors

Brain and other nervous system tumors are the second most diagnosed cancer in children. Low-grade glioma is the most common type of brain tumor in children. These are slow-growing tumors that can often be cured with surgery alone. However, depending on their location in the brain, some low-grade gliomas cannot be fully removed, for example, if they are adjacent to vital structures in the brain. Additionally, in some cases low-grade gliomas may grow back even after complete surgical removal. Traditionally, most children whose tumors are not surgically removable or have come back after surgery receive chemotherapy. While often effective, chemotherapy is associated with substantial side effects. Therefore, alternative treatments for these children are an urgent need.

Alterations in the BRAF gene leading to aberrant activation of the BRAF protein signaling pathway are common in pediatric low-grade gliomas. The BRAF protein has a critical role in controlling cell growth. The BRAF gene is altered in approximately 6 percent of all human cancers (402)Desai AV, et al. (2022) Journal of Clinical Oncology, 40: 4107.. Most cancer-related changes in the BRAF gene cause the protein to continuously stay active, thus helping cancer cells grow faster than normal cells. Common cancer-related changes in the BRAF gene include structural variations such as BRAF gene fusions or rearrangements and/or single base changes such as the BRAF V600E mutation. BRAF structural variations are more common than BRAF V600E mutations in children and adolescents with low-grade gliomas (357)Fangusaro J, et al. (2024) Neuro Oncol, 26: 25..

A combination of two molecularly targeted therapeutics that target BRAF and MEK—another protein that is part of the BRAF signaling pathway—dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and trametinib (Mekinist), was approved by FDA in March 2023 for children with low-grade glioma that has a BRAF V600E mutation. The approval was based on data from a clinical trial of children with BRAF V600–mutant low-grade glioma, in which the combination significantly outperformed chemotherapy, shrinking tumors more often, keeping the cancer from growing nearly three times longer, and causing fewer serious side effects (358)Bouffet E, et al. (2023) N Engl J Med, 389: 1108.. Emerging evidence suggests that the combination treatment may also be effective in children with more advanced gliomas (359)Hargrave DR, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 5174..

The dabrafenib and trametinib combination, however, does not work in patients who have BRAF gene fusions or rearrangements. Therefore, FDA approval of tovorafenib (Ojemda) in April 2024 for patients 6 months and older with relapsed or treatment-unresponsive low-grade glioma that has a BRAF fusion or rearrangement, or the V600 mutation, brings hope to many more parents and families whose children are diagnosed with glioma. The approval was based on a clinical trial in which tumors shrank or disappeared entirely in almost 70 percent of children treated with tovorafenib (360)Kilburn LB, et al. (2024) Nat Med, 30: 207..

Researchers are now investigating whether tovorafenib in combination with chemotherapy could be used as the initial therapy to treat children with low-grade gliomas that have fusions, rearrangements, or other mutations in the BRAF gene (361)van Tilburg CM, et al. (2024) BMC Cancer, 24: 147.. Additionally, researchers are evaluating a separate molecularly targeted therapy, selumetinib (Koselugo), as the initial treatment after surgery for children with low-grade glioma regardless of their BRAF status. Selumetinib blocks the function of MEK and was approved by FDA in 2020 for the treatment of a different childhood tumor known as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)–related plexiform neurofibroma.

While rare in children, low-grade gliomas with mutation in the IDH1 or IDH2 genes are common malignant primary brain tumors diagnosed in young adults. Patients with IDH-mutated astrocytoma have a median age at diagnosis of 36 years (362)Molinaro AM, et al. (2019) Nature Reviews Neurology, 15: 405.. Patients with IDH-mutant gliomas often receive a combination of radiation and chemotherapy after surgery, especially if they are at high risk of disease progression. While this regimen can keep the cancer in check for years, it is not curative and can lead to serious long-term side effects.

Research has shown that mutations in the IDH1 or IDH2 genes result in abnormal IDH1 and IDH2 proteins, leading to the production of an abnormal molecule, 2-hydroxyglutarate, which causes widespread epigenetic changes that disrupt normal cell function and drive brain tumor development (363)Dang L, et al. (2009) Nature, 462: 739.(364)Duncan CG, et al. (2012) Genome Res, 22: 2339.(365)Koivunen P, et al. (2012) Nature, 483: 484.(366)Turcan S, et al. (2012) Nature, 483: 479.. These findings led to the investigation of therapeutic approaches for treating IDH1– and IDH2-mutant brain tumors by blocking the production or effects of 2-hydroxyglutarate. Building on this work, scientists developed vorasidenib (Voranigo), a molecularly targeted therapeutic that blocks the altered IDH1 and IDH2 proteins and substantially reduces levels of 2-hydroxyglutarate and the associated epigenetic changes related to IDH1 or IDH2 gene mutations (367)Mellinghoff IK, et al. (2023) Nat Med, 29: 615..

In August 2024, vorasidenib was approved by FDA for patients 12 years and older with certain slow-growing gliomas, known as grade 2 astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma, that have IDH1 or IDH2 mutation, after patients have undergone surgery, whether a full removal, partial removal, or just a biopsy of the tumor. FDA approval was based on results from a clinical trial demonstrating vorasidenib significantly delayed tumor progression. Patients who received vorasidenib had a 61 percent lower risk of tumor progression compared to those who received a placebo (367)Mellinghoff IK, et al. (2023) Nat Med, 29: 615.(368)Mellinghoff IK, et al. (2023) N Engl J Med, 389: 589.. Ongoing research is evaluating potential mechanisms of resistance to vorasidenib as well as its effectiveness in combination with immunotherapy.

Researchers are also exploring new and improved therapeutic options for children with high-grade brain tumors such as diffuse midline glioma (DMG), a fast-growing, highly aggressive cancer arising in the brain or spinal cord. DMGs with an H3K27M mutation are rare but aggressive cancers that mostly affect pediatric population and young adults. The H3K27M mutation is a change in a protein called histone H3, which helps package DNA and control how genes are switched on and off (see Epigenetic Modifications). DMGs with the H3K27M mutation typically occur in critical areas such as the brainstem or thalamus, where surgery is not possible, and standard treatment with radiation has limited benefit.

Despite many clinical trials, no treatments have improved survival until recently, and most patients live only 11 to 15 months after diagnosis (369)Venneti S, et al. (2023) Cancer Discov, 13: 2370.. Therefore, FDA approval of dordaviprone (Modeyso) in August 2025 offers new hope for patients such as Kaley Ihlenfeldt and their families facing this devastating disease. Dordaviprone works by targeting two important proteins involved in certain brain tumors. First, it blocks dopamine receptors, which are proteins on the surface of brain cells that normally respond to the chemical messenger dopamine in the brain. In some aggressive brain cancers, these receptors are overactive and help tumors grow. Second, dordaviprone activates the protein caseinolytic protease P inside mitochondria, the organelles that provide energy to cells. By activating this protein, dordaviprone disrupts the mitochondrial function, causing stress that leads to cancer cell death. This combined effect helps slow tumor growth.

FDA granted approval to dordaviprone for adults and children age 1 year and older with DMG that has an H3K27M mutation and has worsened after earlier treatment. This is the first approval of a systemic therapy for DMG, marking an important milestone for patients who previously had no effective options. The approval was based on data from five clinical studies showing that about 20 percent of patients responded to the treatment (369)Venneti S, et al. (2023) Cancer Discov, 13: 2370.(370)Arrillaga-Romany I, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 1542.. Among those who responded, 73 percent experienced benefits lasting at least 6 months, and 27 percent had benefits lasting a year or longer.

Researchers are also examining CAR T-cell therapy, a form of cellular immunotherapy, in some children and young adults with a highly aggressive form of DMG, called diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) (see A New Age of Cell Therapies) (371)Majzner RG, et al. (2022) Nature, 603: 934.(372)Monje M, et al. (2025) Nature, 637: 708.. The CAR T cells—which in this case target the tumor-associated GD2 glycolipid (a lipid molecule attached to a carbohydrate molecule) on the surface of DIPG cells—are administered in small doses and infused directly into the brain. Initial findings from the study reported positive responses in terms of reductions in tumor size as well as improvements in cancer-related symptoms.

Expanding Treatment Options for Patients with Solid Tumors

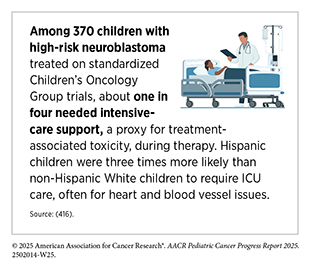

Neuroblastoma is the most common solid tumor outside the brain in children. Despite recent advances, only around 50 percent of children with high-risk neuroblastoma survive 5 years or longer. Patients whose cancer has come back have a poor outcome, with a 5-year overall survival of less than 10 percent (373)Oesterheld J, et al. (2024) J Clin Oncol, 42: 90.. Therefore, additional treatment options are urgently needed. In this regard, in December 2023, FDA approved the first therapeutic with the potential to reduce the risk of relapse in children with high-risk neuroblastoma. The treatment, eflornithine (Iwilfin), was approved for adult and pediatric patients with high-risk neuroblastoma with at least a partial response to prior therapies, including anti-GD2 immunotherapy. Eflornithine blocks the function of a protein, ornithine decarboxylase, which has a high activity in tumor cells and promotes tumor cell proliferation.

NF1 is an inherited genetic disorder that causes severe symptoms and complications including a significantly increased risk for developing various types of tumors (see Figure 4). Although the tumors that develop in individuals with NF1 are usually benign, some patients develop malignant tumors, usually in adolescence or adulthood. Plexiform neurofibromas (PN) are tumors arising in cells that form the covering of peripheral nerves. These benign tumors occur in up to 50 percent of patients with NF1 and can cause pain, disability, and disfigurement. They can also go on to become cancerous.

Research has demonstrated that the growth of PN in patients with NF1 is fueled by a signaling pathway that includes MEK proteins, a large family of proteins that helps control cell division, cell maturation, and cell death (374)Moertel CL, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol, 43: 716.. In 2020, FDA approved a MEK-targeted therapeutic, selumetinib (Koselugo), for treating pediatric patients age 2 years and older who have NF1-related PN that cannot be safely removed surgically. FDA approval was expanded in September 2025 to include patients 1 year and older. The 2020 approval was based on results from a phase II clinical trial showing that 66 percent of pediatric patients who received selumetinib had partial tumor shrinkage (375)Dombi E, et al. (2016) N Engl J Med, 375: 2550.. In addition, many of the children reported experiencing reduced pain, which is one of the most common neurofibroma-related symptoms. More recently, researchers have demonstrated that with up to 5 years of additional selumetinib treatment, most children with PN have durable tumor shrinkage and sustained improvement in pain (376)Gross AM, et al. (2023) Neuro Oncol, 25: 1883..

In February 2025, FDA approved a second MEK-targeted therapeutic, mirdametinib (Gomekli), for both adult and pediatric patients 2 years of age and older with NF1 who have symptomatic PN not amenable to complete resection. The approval was based on results from a phase II clinical trial indicating that 52 percent of pediatric patients who received mirdametinib had tumor shrinkage (374)Moertel CL, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol, 43: 716.. Mirdametinib and selumetinib have been approved by FDA as suspension or granule formulation, which do not require swallowing of whole capsules making it easier for children who may have difficulty swallowing capsules, such as younger children. The approval of mirdametinib is bringing new hope to patients such as Alexander Owens and their family.

Childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors are rare cancers in hormone-producing cells, most often found in the appendix, where they usually grow slowly. Tumors in other digestive organs, including the pancreas, are less common and may behave more aggressively. In March 2025, FDA approved the molecularly targeted therapeutic cabozantinib (Cabometyx) for treating children 12 years and older with pancreatic or non-pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors that have spread or are not surgically removable and have not responded to earlier treatments. Blood vessel growth helps neuroendocrine tumors develop. Cabozantinib blocks several key signals including VEGF, which stimulates blood vessel growth and was previously approved for the treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer in children 12 years and older.

How and when genes are turned “on” or “off ” is regulated by special factors called epigenetic modifications (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers). The sum of these modifications across the entire genome is called the epigenome. Genetic mutations that disrupt the epigenome can lead to cancer development. For example, mutations in the SMARCB1 gene that lead to loss of the corresponding BAF47 protein, which helps regulate cell growth by controlling epigenetics, drive more than 90 percent of cases of epithelioid sarcoma, a rare type of slow-growing cancer that develops in deep soft tissue or the skin of a finger, hand, forearm, lower leg, or foot (377)Gounder M, et al. (2020) Lancet Oncol, 21: 1423..

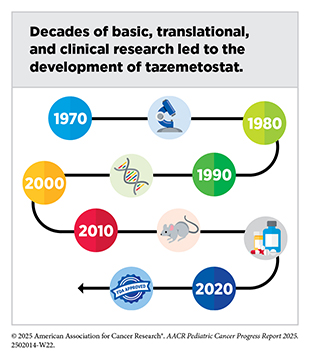

Researchers found that the multiplication and survival of cancer cells lacking BAF47 depend on EZH2, a protein that adds epigenetic modifications called methyl groups to histones (378)Kim KH, et al. (2015) Nat Med, 21: 1491.. The molecularly targeted therapeutic tazemetostat (Tazverick) targets EZH2, preventing it from adding methyl groups to histones. It was approved by FDA in January 2020, for treating patients age 16 or older with metastatic or locally advanced epithelioid sarcoma that cannot be completely removed with surgery.

Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome (VHL) is an inherited disorder characterized by the formation of tumors (e.g., kidney cancer and pancreatic cancer) and benign cysts in different parts of the body (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers). Individuals with VHL develop tumors most frequently during young adulthood. Belzutifan (Welireg), the first drug for the treatment of VHL-associated tumors, was approved by FDA in August 2021. In May 2025, FDA expanded the use of belzutifan as the first oral therapy for the treatment of children 12 years and older and adults with pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma—rare tumors that develop in the adrenal glands or nearby nerves—that have spread or are not surgically removable.

Advances in Biomarker-based Treatments

The characterization of genetic alterations that drive tumor growth has been instrumental in understanding tumor biology and conducting genetically informed clinical trials such as basket, umbrella, and platform clinical trials (see Figure 9). These advances have accelerated the pace of development and FDA approvals of molecularly targeted therapeutics and immunotherapeutics that are effective against cancers that originate at different sites in the body but share biological underpinnings. In fact, one of the most notable achievements in precision medicine was the first FDA approval of a molecularly targeted therapeutic to treat cancer based on the presence of a specific genetic biomarker in the tumor irrespective of the site at which the tumor originated. This therapeutic, larotrectinib (Vitrakvi), was approved by FDA in 2018 for treating children and adults who have solid tumors with NTRK gene fusions.

Larotrectinib works by targeting three related proteins called TRKA, TRKB, and TRKC. The genes NTRK1, NTRK2, and NTRK3 provide the code that cells use to make these proteins. Genetic alterations known as structural variations that involve the three NTRK genes and lead to the production of NTRK gene fusions, and subsequently to TRK fusion proteins, drive the growth of several cancer types that occur in children and AYAs, including rare sarcomas such as infantile fibrosarcoma and certain types of brain tumors. NTRK gene fusions fuel the growth of less than 1 percent of all solid tumors overall but the frequency is higher in pediatric cancers (379)O’Haire S, et al. (2023) Scientific Reports, 13: 4116.(380)Zhao X, et al. (2021) JCO Precis Oncol, 1..

Larotrectinib was approved based on findings from three basket trials (see Figure 8) showing that 75 percent of patients treated with the molecularly targeted therapeutic had complete or partial tumor shrinkage (278)Drilon A, et al. (2018) N Engl J Med, 378: 731.. Since the approval of larotrectinib, two additional molecularly targeted therapeutics, entrectinib and repotrectinib, have been approved by FDA for treating children with solid tumors based on the same NTRK gene fusion biomarker (see Figure 12). The approvals of larotrectinib, entrectinib, and repotrectinib for use in a tissue-agnostic way followed several decades of research in cancer science and medicine.

The approval of repotrectinib in June 2024 for children 12 years and older and adults was based on findings from a clinical trial that evaluated the therapeutic in patients who had or had not received a prior TRK-targeted therapy. The study showed that tumors shrank in nearly 60 percent of patients who had not received a prior TRK-targeted therapy and in half of patients who had received a prior TRK-targeted therapy (381)US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Briefing Document. Pediatric Oncology Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC). Accessed: August 31, 2025.. Ongoing research is evaluating the efficacy of NTRK inhibitors as the initial treatment for several types of pediatric cancer (382)Laetsch TW, et al. (2025) J Clin Oncol, 43: 1188.(383)Desai AV, et al. (2025) Eur J Cancer, 220: 115308.(384)Hong DS, et al. (2025) ESMO Open, 10: 105110..

Mutations in the RET gene, including single base changes, fusions, and deletions that lead to abnormal activation of the RET protein, are rare alterations observed mostly in patients with certain types of thyroid cancer and lung cancer (385)Duke ES, et al. (2023) Clin Cancer Res, 29: 3573.. In children and AYA patients, RET mutations are frequently reported in papillary thyroid carcinomas and medullary thyroid cancers and less frequently in glioma, lipofibromatosis, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, and infantile myofibromatosis (386)Ortiz MV, et al. (2020) JCO Precis Oncol, 4: 341..

A RET-targeted therapeutic, selpercatinib, was approved by FDA first in 2020, for children 12 years and older with certain types of advanced thyroid cancer caused by changes in the RET gene. In May 2024, FDA approved selpercatinib for the treatment of pediatric patients 2 years and older with metastatic thyroid cancer or any solid tumor with a RET gene alteration, as detected by an FDA-approved test. The approval was based on the findings of a clinical trial in which nearly 50 percent of patients treated with selpercatinib saw their tumors shrink. In addition to selpercatinib, FDA has also approved another RET-targeted therapeutic, pralsetinib (Gavreto), for children with thyroid cancer with RET alterations.

Advances in Pediatric Cancer Treatment With Immunotherapy

The immune system is a complex network of cells (called white blood cells; see Sidebar 14), tissues (e.g., bone marrow), organs (e.g., thymus), and the substances they make that help the body fight infections and other diseases, including cancer. The immune system actively monitors threats from external sources (such as viruses and bacteria) and internal sources (such as abnormal or damaged cells) and works to eliminate them from the body.

The immune system is highly effective in detecting and eliminating cancer cells, a process also known as cancer immune surveillance (388)Hiam-Galvez KJ, et al. (2021) Nat Rev Cancer, 21: 345.. During the course of cancer development (see Unraveling the Genomics and Biology of Pediatric Cancers), some cells find ways to “hide” from the immune system, such as by decreasing or eliminating the numbers and/or amounts of proteins on the surface of tumor cells that are used by the immune system to recognize cancer cells. This acquired property of cancer cells triggers certain brakes on immune cells that prevent them from eradicating cancer cells, and releases molecules that weaken the ability of immune cells to detect and destroy cancer cells (389)Mishra AK, et al. (2022) Diseases, 10: 60.. The field of cancer immunology is focused on better understanding how tumor cells evade the immune system and leveraging this knowledge to develop novel cancer treatments.

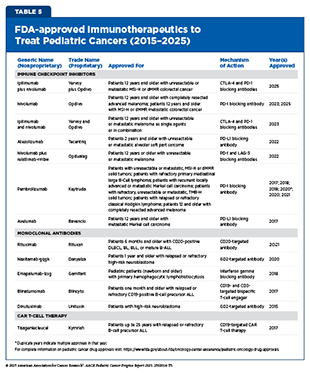

Cancer immunotherapy refers to any treatment that works by using the immune system to eliminate cancer. Unprecedented advances in cancer immunology have firmly established immunotherapy as the fifth pillar of cancer medicine, with transformative impact in certain childhood cancers such as B-ALL and neuroblastoma (see Table 5) (390)Kaufmann SHE (2019) Front Immunol, 10: 684.. However, the benefits of immunotherapy have not yet been as widespread in children as they have been in adult cancers, for which these therapies have transformed outcomes in previously intractable diseases such as advanced lung cancer and metastatic melanoma.

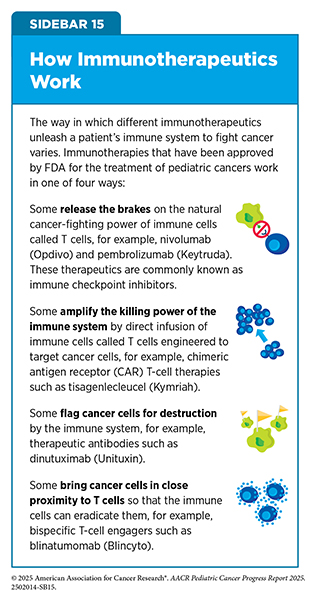

Different immunotherapeutics unleash the immune system in various ways to fight cancer (see Sidebar 15). The following sections highlight the immunotherapeutics that have been approved by FDA for childhood cancers over the past 10 years.

Boosting the Cancer-killing Power of Immune Cells

Research has demonstrated that immune cells, such as T cells, are naturally capable of destroying cancer cells. It has also shown that in patients with cancer, often the numbers of cancer-killing T cells are insufficient, and that the cancer-killing T cells that are present are unable to find or destroy the cancer cells for one of several reasons. This knowledge has led researchers to identify several ways to boost the ability of T cells to eliminate cancer cells.

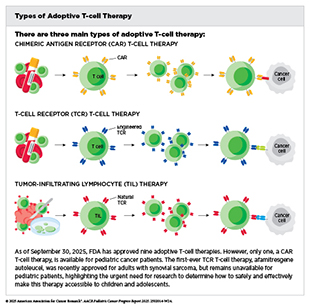

Adoptive cell therapy, also called cellular immunotherapy, is designed to dramatically increase the number of cancer-killing immune cells a patient has, thereby boosting the immune system’s ability to seek and destroy cancer cells (391)Rohaan MW, et al. (2019) Virchows Arch, 474: 449.. CAR T-cell therapy is one type of cellular immunotherapy that has generated enormous excitement in pediatric oncology in recent years because this treatment has demonstrated unprecedented efficacy in some children with advanced leukemia.

CAR T-cell therapy is the culmination of decades of research utilizing knowledge of the cellular and molecular components of the immune system, genetic engineering, and the biological underpinnings of blood cancers. It works by collecting a patient’s own immune cells (T cells) and genetically modifying them to produce a special receptor, called a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), on their surface. This receptor enables the T cells to recognize and attack cancer cells. After being expanded in numbers in the laboratory, these engineered cells are infused back into the patient to target and destroy the cancer.

The first CAR T-cell therapy tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah) was approved by FDA in 2017 and as of September 30, 2025, is the only approved cellular immunotherapy for pediatric cancers. It was approved for the treatment of children and young adults with B-ALL that had not responded to standard treatments or had relapsed at least twice. Tisagenlecleucel is developed by genetically modifying a patient’s T cells to have a CAR that targets the molecule CD19, a protein found on the surface of immune cells called B cells, as well as on the surface of several types of leukemia and lymphoma cells that arise in B cells, including most cases of ALL. The approval was based on results from a phase II clinical trial indicating that more than 80 percent of the children and young adults with multiply relapsed leukemia who were treated with tisagenlecleucel had remission within 3 months of receiving the CAR T-cell therapy (392)Maude SL, et al. (2018) N Engl J Med, 378: 439..

This revolutionary immunotherapeutic has been transformative for children with ALL, such as Lianna Munir. CAR T-cell therapy has led to complete remission for some patients whose leukemia has returned or stopped responding to other treatments. A long-term follow-up of patients treated with tisagenlecleucel showed that more than 60 percent were living 3 years or longer after their first infusion of CAR T cells (393)Laetsch TW, et al. (2023) Journal of Clinical Oncology, 41: 1664.. Additionally, more than 50 percent of patients were living without their disease coming back 3 years after treatment completion, suggesting that CAR T cells can lead to durable cancer control.