- Research: Driving Progress Against Cancer

- Cancer: An Ongoing Challenge

- Inequities in the Burden of Cancer in the United States

- Variable Progress Against Different Types of Cancer and Stages of Diagnosis

- The Growing Population Burden of Cancer

- The Global Burden of Cancer

- Funding Cancer Research: A Vital Investment

Cancer in 2025

In this section, you will learn:

- In the United States (US), the overall cancer death rate has been steadily declining since the 1990s, translating into more than 4.5 million cancer deaths avoided between 1991 and 2023.

- The decline in overall US cancer death rate is attributable to reduction in smoking rates, as well as improvements in treatment and early detection of certain cancers.

- Approximately 18.6 million cancer survivors were living in the US as of January 1, 2025.

- Progress has not been equal against all cancer types or all stages of a given cancer type.

- Many segments of the US population experience stark inequities in the cancer burden; these inequities are largely driven by structural and social factors.

- The economic burden of cancer on individuals and the US health care systems is expected to rise in the coming decades, highlighting the urgent need for more research and increased federal support for medical science and public health.

- It is imperative that all stakeholders work together to implement evidence-based interventions, including public policies that guarantee equitable access to quality health care for all patients.

Research: Driving Progress Against Cancer

Research is the cornerstone of progress against the collection of diseases we call cancer. It drives every basic science discovery, accelerates every clinical breakthrough, and informs public policies designed to improve health outcomes, ultimately leading to better survival and quality of life. Advances across basic, clinical, translational, and population sciences, along with technological innovations such as artificial intelligence and machine learning (see Envisioning the Future of Cancer Science and Medicine), are fueling new strategies for cancer prevention, early detection, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care.

Every scientific innovation and effective policy that drives progress against cancer represents the culmination of a complex process shaped by years of coordinated effort and multidisciplinary collaboration among diverse stakeholders (see Sidebar 1).

Remarkable progress against cancer—in particular, improvements in early detection, diagnosis, treatment, and risk reduction—has led to a steady decline in US cancer death rates over the past several decades. Between 1991 and 2023, the age-adjusted overall cancer mortality rate declined by 34 percent, a reduction that translates into averting more than 4.5 million deaths from cancer (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.. The steady progress in reducing cancer mortality is largely attributable to reduced smoking rates and subsequent declines in lung cancer mortality, declines that have accelerated in recent years due to advances in treatment and early detection (see Matching Therapies to the Molecular Drivers of Lung Cancer) (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10..

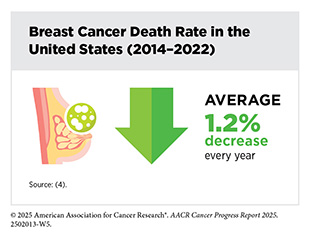

Declines in death rates for colorectal cancer and female breast cancer have also contributed to the progress in reducing overall US cancer mortality (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.. According to a recent analysis, US breast cancer mortality declined by 44 percent, averting more than 517,000 deaths between 1989 and 2022, owing to advances in screening mammography and personalized treatments (see Cancer Screening for Early Detection) (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.(3)Giaquinto AN, et al. (2024) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 477.. Similarly, the death rate for colorectal cancer declined by 49 percent between 1990 and 2023 (4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.. However, this progress has been limited to older adults, as colorectal cancer death rates among those diagnosed before age 50 increased by approximately 14 percent between 1990 and 2023 (4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025..

Breakthroughs across the spectrum of cancer science and medicine have led to unprecedented progress against aggressive cancers once considered intractable. Research-driven advances in treatment have resulted in a steady decline in death rates for leukemia, melanoma, and kidney cancer, despite increasing incidence of these cancers (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10..

For example, groundbreaking basic research in the 1960s through 1980s that identified the mechanistic underpinnings of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), a cancer of the blood and bone marrow, propelled the development of a cascade of new treatments for CML that have drastically improved outcomes for these patients (see Leukemias) (5)Howlader N, et al. (2023) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 32: 744.. As a result, the 5-year relative survival rate for CML has more than tripled, from 22 percent in the mid-1970s to 70 percent among individuals diagnosed between 2015 and 2021 (4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.(6)American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Accessed: June 13, 2025..

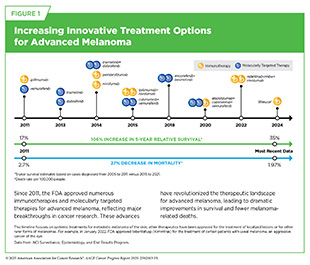

More recently, advances in molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapies have transformed clinical care for several previously difficult-to-treat cancers, including metastatic melanoma (see Figure 1), lung cancer (see Matching Therapies to the Molecular Drivers of Lung Cancer), kidney cancer, and certain types of breast cancer. For example, the immunotherapy pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was recently shown to be the first postsurgical treatment to extend survival in patients with early-stage kidney cancer (7)Choueiri TK, et al. (2024) N Engl J Med, 390: 1359..

Among the major advances made across the clinical cancer care continuum from July 1, 2024, to June 30, 2025, are 20 new anticancer therapeutics that were approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). During this period, FDA also approved new uses for eight previously approved anticancer therapeutics and one cancer treatment device; two new early detection screening tests, including the first liquid biopsy test and a next-generation multitarget stool DNA test for colorectal cancer screening; a device for at-home sample collection for cervical cancer screening; and a wearable device that uses low-intensity electrical fields to slow the growth of lung cancer cells. FDA also approved a number of artificial intelligence-powered devices and software for aiding cancer risk prediction, diagnosis, and early detection.

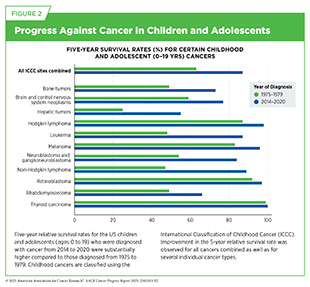

Collectively, advances such as these—as well as those highlighted in past 14 editions of this annual report—are helping more children and adults live longer, fuller lives following a cancer diagnosis, with fewer treatment-related side effects. The 5-year relative survival rate for all cancers combined has increased from 49 percent for those diagnosed between 1975 and 1977 to 70 percent among those diagnosed between 2015 and 2021 (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.(4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.. Similar progress has been made among US children (ages 0 to 14) and adolescents (ages 15 to 19), diagnosed with cancer whose 5-year relative survival rates increased from 58 percent to 85 percent in children and from 68 percent to 87 percent in adolescents over the same time period (see Figure 2) (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.(8)National Cancer Institute. Cancer in children and adolescents. Accessed: June 30, 2025..

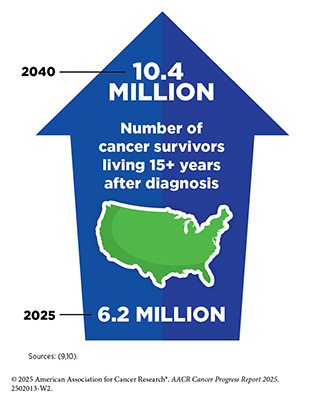

In 2011, when the inaugural AACR Cancer Progress Report was released, there were an estimated 12 million cancer survivors living in the United States. As of January 1, 2025, the number of people living with a history of cancer had grown to 18.6 million, representing approximately 5.5 percent of the US population (9)Wagle NS, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin.. This reflects a nearly four-fold increase compared to 50 years ago, when cancer survivors made up only 1.4 percent of the US population. The number of cancer survivors is projected to grow to over 22 million by 2035 (9)Wagle NS, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin..

Thanks to remarkable advances in cancer research, cancer survivors are now living years, even decades, beyond their initial diagnosis. As of 2025, nearly 50 percent of US cancer survivors have lived 10 years or more since their cancer diagnosis, and 22 percent have lived 20 years or more (9)Wagle NS, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin.. Moreover, nearly 80 percent of US cancer survivors are age 60 or older, and this proportion is expected to increase with continued advances in treatment and the aging of the population (9)Wagle NS, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin.. As the population of cancer survivors grows, prioritizing research that addresses their evolving needs must remain a critical focus for US medicine and public health (see Supporting Cancer Patients and Survivors).

Cancer: An Ongoing Challenge

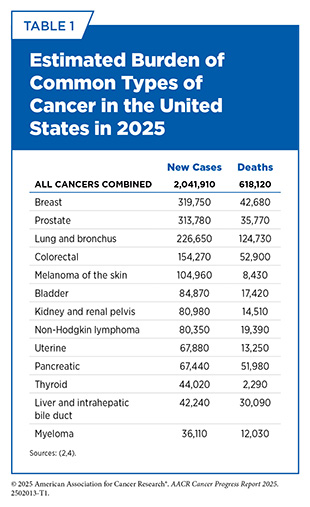

While substantial progress has been made against cancer, the disease continues to be an enormous public health challenge in the United States and around the world. In 2025, an estimated 2,041,910 new cancer cases will be diagnosed and 618,120 people will die from the disease in the United States (see Table 1). In addition, many population groups in the United States experience disproportionately high rates of cancer incidence and mortality.

Inequities in the Burden of Cancer in the United States

Despite overall progress against cancer, significant disparities persist among certain population groups in the United States, across the cancer continuum, linked to structural and socioeconomic disadvantages. Because of a long history of structural inequities and systemic injustices, certain segments of the US population continue to shoulder a disproportionate burden of adverse health conditions, including cancer. These unequal burdens have led researchers and public health experts to closely study cancer disparities.

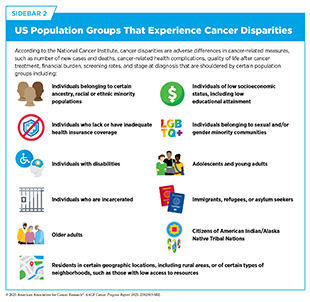

Cancer disparities are one of the most pressing public health challenges in the United States. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) defines cancer disparities as adverse differences in cancer-related measures, such as number of new cases, number of deaths, cancer-related health complications, survivorship and quality of life after cancer treatment, screening rates, and cancer stage at diagnosis, that exist among certain population groups (see Sidebar 2).

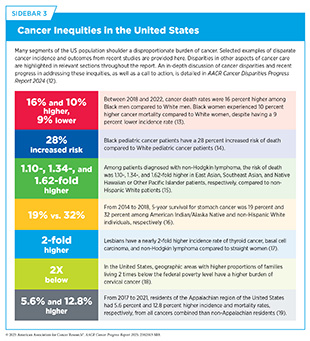

The AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024 (12)American Association for Cancer Research®. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024. Accessed: June 14, 2025. highlights the disproportionate burden of cancer among US racial and ethnic minority groups and other medically underserved populations (see Sidebar 3). As one example, while non-Hispanic (NH) White individuals have the highest overall cancer incidence rate, NH Black individuals had the highest overall cancer mortality rate, followed by American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN). Further, between 2015 and 2021, patients with cancer from all racial and ethnic minority groups had lower 5‐year relative survival rates (61.7 to 68.4 percent) than NH White individuals (70.8 percent) (4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025..

Research on the science of cancer disparities is revealing significant differences in incidence and mortality across subpopulations within racial and ethnic groups, underscoring the need to disaggregate data within these populations. Striking disparities in cancer burden have been identified within Asian subpopulations and between Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) and Asian individuals (12)American Association for Cancer Research®. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2024. Accessed: June 14, 2025.. As an example, the risk of death from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma was 10 percent and 22 percent higher among East Asians and Pacific Islanders, respectively, compared to South Asians (20)Wu C, et al. (2024) Cancer Res Commun, 4: 2153.. Notably, the US Asian population has ancestry in numerous countries of origin, and the NHOPI population comprises diverse subgroups with distinct variations in historical backgrounds, languages, and cultural traditions. Still, Asian and NHOPI populations continue to be grouped together in cancer epidemiologic data.

Cancer disparities are caused by many overlapping factors at the individual, community, and societal levels. These include aspects like biology, personal behaviors, access to healthy environments, cultural influences, and differences in quality of health care systems, factors that can affect people throughout their lives (22)Alvidrez J, et al. (2019) Am J Public Health, 109: S16.. To help researchers understand and address these influences, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities developed a framework to guide the study of contributors to adverse health outcomes and health disparities, including those related to cancer (22)Alvidrez J, et al. (2019) Am J Public Health, 109: S16.. This framework emphasizes the importance of addressing both biological drivers and social drivers of health (SDOH) simultaneously, rather than focusing on any one driver in isolation.

NCI defines SDOH, sometimes also called social determinants of health, as the social, economic, and physical conditions in the places where people are born and where they live, learn, work, play, and get older that can affect their health, well-being, and quality of life. SDOH include factors such as socioeconomic status; housing; transportation; and access to healthy food, clean air and water, and health care services (see Figure 3).

It is important to recognize that patients with intersectional identities—such as individuals from racial and ethnic minority populations living in disadvantaged rural or urban areas—often face multilevel barriers to cancer care that negatively impact screening, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. As an example, Black women living in more socially disadvantaged neighborhoods had significantly worse breast cancer survival compared to those living in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods, even after accounting for clinical and individual socioeconomic factors (23)Holder EX, et al. (2025) JAMA Netw Open, 8: e253807.. Neighborhood disadvantage is measured using a weighted composite score based on neighborhood-level characteristics, including the proportion of Black residents, individuals living below the federal poverty level, those receiving public assistance, living in female-headed households, unemployed, or under 18 years of age. Higher scores reflect greater levels of disadvantage.

Inadequate access to quality health care is a major social driver of cancer disparities. A recent review of disparities across the lung cancer continuum revealed that individuals who were younger and not eligible for Medicare had lower screening rates; uninsured patients or those with Medicaid were less likely to receive curative surgery; and individuals with Medicaid or no insurance were less likely to utilize novel therapies and enroll in clinical trials (24)Bade B, et al. (2025) Chest.. Similar patterns have been observed in breast cancer care, in which women with private insurance were significantly more likely to receive molecularly targeted therapy or immunotherapy, treatments associated with better outcomes (25)Ajjawi I, et al. (2025) Breast Cancer Res Treat, 212: 299.(26)Ajjawi I, et al. (2025) Cancers (Basel), 17..

Cancer disparities affect multiple segments of the US population, making disparities a significant public health concern that requires tailored efforts to better understand and address these inequities (see Addressing Cancer Disparities and Improving Patient Outcomes). Health equity for all populations can only be achieved through new insights gained from innovative, inclusive, and translational science. This includes basic research using biospecimens from diverse populations; clinical studies with participants from all sociodemographic backgrounds; and health care delivery and implementation research that reflects every community.

Variable Progress Against Different Types of Cancer and Stages of Diagnosis

A significant challenge in cancer science and medicine is the uneven progress against different cancer types and different stages of a given cancer type. This challenge is reflected in the wide variation in 5-year relative survival rates among US cancer patients, depending on both the type of cancer diagnosed and the stage at diagnosis (4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025..

For example, the overall 5-year relative survival rate is just 13 percent for pancreatic cancer and 6 percent for glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), an aggressive form of brain cancer, in stark contrast with 92 percent for breast cancer and 98 percent for prostate cancer (4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025.. However, when examining stage-specific 5-year survival rates for breast and prostate cancers, striking differences emerge. Individuals diagnosed with localized disease—cancer that is confined to the breast or prostate tissues—have a 5-year relative survival rate of 100 percent, while individuals diagnosed with metastatic disease—disease that has spread to other organs—have a 33 and 38 percent 5-year relative survival rate, respectively.

Variable progress against different cancer types can be explained in part by disparities in lifesaving therapeutic options that are available for different cancer types. For example, since the release of the first edition of this report in 2011, FDA has approved 20 new molecularly targeted therapeutics, excluding endocrine therapies, and two immunotherapeutics for treating patients with breast cancer. As a result, patients have a deeper selection of therapeutics for the treatment of their disease and breast cancer mortality has been declining steadily.

In contrast, treatment options for patients with GBM remain extremely limited. Since the approval of the chemotherapeutic temozolomide nearly 25 years ago, no new anticancer agents have shown promise in improving overall survival. This in part explains why the 5-year relative survival rate for patients with GBM remains at a dismal 6 percent (4)NCI Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. NCI SEER*Explorer. Accessed: June 31, 2025..

Developing new and effective tests for the early detection of more cancer types (see Cancer Screening for Early Detection), in addition to expanding the eligibility for established screening recommendations (27)Rode MM, et al. (2025) J Thorac Oncol., could also help address the challenges of variable progress between different types of cancer, since the likelihood of a better outcome is much higher when cancer is diagnosed at an early stage, when it is confined to its original location and not spread to distant sites (see Cancer Screening for Early Detection and Figure 12). Additionally, improving and expanding therapeutic options for difficult-to-treat cancers will require intensive research that builds on existing knowledge to uncover the biological drivers of these diseases and inform the development of more effective treatments.

The Growing Population Burden of Cancer

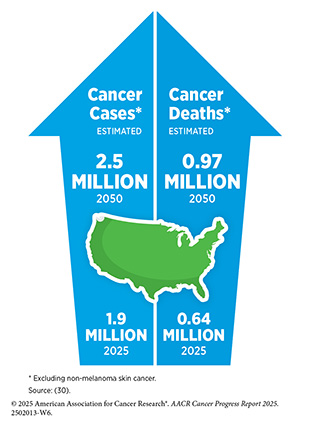

The public health challenge posed by cancer is expected to increase even further in the coming decades unless more effective strategies for prevention, early detection, and treatment are implemented. In the United States, the number of new cancer cases (including non-melanoma skin cancer) diagnosed annually is projected to exceed 3.5 million by 2050—a nearly 40 percent increase from 2025 estimates (28)Bizuayehu HM, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2443198.. A major driver of this rise is the growing proportion of older adults in the population, as cancer risk increases significantly with increasing age. In fact, in 2022, 59 percent of all cancer cases occurred in individuals age 65 and older. By 2050, this age group is projected to exceed 82 million people, representing about 23 percent of the total US population. That is a 50 percent increase from 2022, when there were about 58 million older adults, making up roughly 17 percent of the population (29)Bizuayehu HM, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 3708.. Notably, cancer cases in the age 65 and older population have remained steady over time, from 61 percent in 1995 to 59 percent in 2021, which could result from the decline in smoking-related cancers in this age group (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10..

Also contributing to the projected increase in the number of US cancer cases is the high prevalence of excess body weight, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, environmental factors, and continued tobacco use (see Reducing the Risk of Cancer Development) (31)Bandi P, et al. (2025) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 34: 836.(32)Islami F, et al. (2018) CA Cancer J Clin, 68: 31.. For example, although smoking rates have declined precipitously since the 1970s, 11 percent of adults still smoke. However, lung cancer is on the rise in non-smokers (33)Luo G, et al. (2025) The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. and makes up about 16 percent and 10 percent of cases diagnosed in women and men, respectively (34)Siegel DA, et al. (2021) JAMA Oncol, 7: 302.. In 2023, individuals who never smoked accounted for more than 20,000 lung cancer–related deaths (34)Siegel DA, et al. (2021) JAMA Oncol, 7: 302.(35)LoPiccolo J, et al. (2024) Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 21: 121..

A recent review found that lung cancer in people who never smoked exhibits unique tumor characteristics and patterns compared to lung cancers caused by tobacco use. Specifically, these cancers are predominantly adenocarcinomas, the type of cancers that start in mucus-producing cells; occur more frequently in women and individuals of Asian ancestry (36)Devarakonda S, et al. (2021) J Clin Oncol, 39: 3747.(37)Ha SY, et al. (2015) Oncotarget, 6: 5465.(38)Dubin S, et al. (2020) Mo Med, 117: 375; and have many changes in the DNA that researchers can target with specific treatments (see Understanding the Path to Cancer Development) (35)LoPiccolo J, et al. (2024) Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 21: 121.. As lung cancer in people who have never smoked is an emerging public health concern, there is a critical need to identify its unique risk factors, conduct in-depth characterization of the disease, and develop evidence-based strategies for early detection and treatment to reduce the burden of lung cancer in patients without a history of smoking.

Although overall cancer incidence in the United States has stabilized in recent years, the incidence of certain cancer types, as well as the age- and sex-specific cases of certain cancers, is increasing. For example, the incidence of pancreatic cancer, liver cancer, uterine cancer, and HPV-associated oral cancers (e.g., base of tongue and tonsils) has been rising (39)American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2023-2024. Accessed: March 17, 2025.. While the overall incidence of lung cancer is declining in the United States, young (30 to 44 years) and middle-aged (45 to 59 years) women are being diagnosed at a higher rate than men in the same age groups (40)Jemal A, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 1727.. In 2021, lung cancer incidence among individuals ages 65 and younger was slightly higher in women than in men (2)Siegel RL, et al. (2025) CA Cancer J Clin, 75: 10.. This reverses the historical trend of a higher incidence among men and cannot be attributed to smoking prevalence.

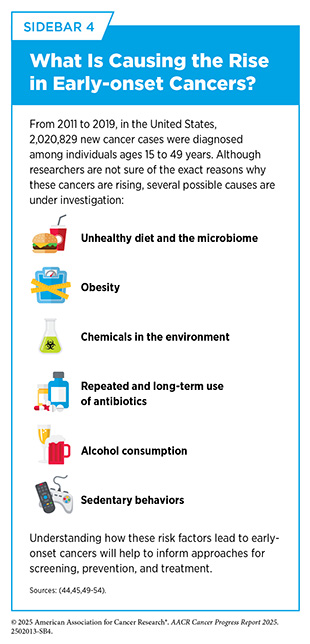

Researchers predict that US individuals born during 1965–1980 (Generation X) will have a higher incidence of cancer as they turn age 60 than those born during 1946–1964 (Baby Boomers) at the same age (41)Rosenberg PS, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2415731.(42)Sung H, et al. (2024) Lancet Public Health, 9: e583.. While the exact reasons remain unclear, the increase is thought to be driven by several factors, including a higher prevalence of modifiable risk factors, such as excess body weight, physical inactivity, and exposure to environmental pollutants. Another rising concern among public health experts is the steadily increasing incidence of certain cancer types among individuals younger than 50, a phenomenon referred to as early-onset cancer.

Understanding the reasons behind rising cases of early-onset cancers is an area of intensive research (see Sidebar 4). From 2010 to 2019, the incidence of 14 cancers—including melanoma, certain lymphomas, and cancers of the cervix, colon, breast, pancreas, stomach, testicles, and uterus—increased in individuals aged 15 to 49 years (44)Shiels MS, et al. (2025) Cancer Discov: OF1.. Notably, early-onset colorectal cancer, which is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, has been linked to a significant accumulation of microplastics in the bodies of Generation X individuals, highlighting a potential contributor to risk for this disease (45)Li S, et al. (2023) Cancers (Basel), 15.. One recent study also implicated bacteria, stating that a DNA-damaging toxin produced by certain strains of the bacterium Escherichia coli may be a key driver in the rise of early-onset colorectal cancer (46)Diaz-Gay M, et al. (2025) Nature..

To reduce the burden of early-onset colorectal cancer and early-onset breast cancer, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), an independent, volunteer panel of experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, has updated their screening guidelines to recommend starting colorectal and breast cancer screening at an earlier age of 45 years and 40 years, respectively, instead of the previously recommended starting age of 50 years (see Cancer Screening for Early Detection). Researchers are also evaluating new and improved strategies including genetic testing and other approaches for prevention and early detection of colorectal cancer in the younger population (47)Chung DC, et al. (2024) N Engl J Med, 390: 973.(48)Seum T, et al. (2025) JAMA Intern Med, 185: 110..

The Global Burden of Cancer

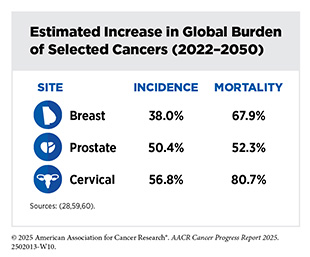

Globally, cancer remains a leading cause of illness and death. According to a recent analysis, there were an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and over 10.3 million deaths from cancer in 2025 (29)Bizuayehu HM, et al. (2024) Cancer, 130: 3708.. An estimated 53.5 million people were living for at least 5 years following a cancer diagnosis. Cancers of the lung, breast, colon and rectum, prostate, and skin (non-melanoma) were the five most frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide in 2022, the most recent year with available data (30)International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory. Accessed: June 30, 2025.(55)World Health Organization. Cancer. Accessed: June 30, 2025.. Accounting for the most cancer-related deaths globally are cancers of the lung, colon and rectum, liver, stomach, and breast (56)Bray F, et al. (2024) CA Cancer J Clin, 74: 229..

Stark disparities in the cancer burden are found among countries with different levels of socioeconomic development. Researchers use metrics, such as the human development index (HDI) or the sociodemographic index (SDI), to identify where countries or geographic areas fall on the spectrum of socioeconomic development. SDI quantification considers income per capita, average years of education, and total fertility rate for citizens younger than 25, whereas HDI measurement considers income per capita, average years of education, and life expectancy at birth.

In low-HDI countries, cancer incidence and mortality are both projected to triple by 2050, in stark contrast to high-HDI countries (28)Bizuayehu HM, et al. (2024) JAMA Netw Open, 7: e2443198., where rates are expected to remain relatively stable. Additionally, compared to North America, a high-HDI region, Africa, a low-HDI region, has the highest mortality-to-incidence ratios (MIRs) (23.0 percent vs. 67.2 percent, respectively)—a metric that reflects the proportion of individuals who die from cancer relative to the number of new cases diagnosed. A high MIR signals that a larger share of people diagnosed with cancer are dying from it and typically points to limited access to timely diagnosis, effective treatment, and quality of cancer care.

Regional disparities are also observed for specific cancer types. For example, from 1990 to 2021, an annual decline in breast cancer incidence ranging from 0.16 percent to 1.14 percent was observed in high-SDI regions such as Central Asia and Eastern and Western Europe. In contrast, low-SDI regions—including North Africa, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa—experienced annual increases in breast cancer incidence ranging from 2 percent to 3.4 percent (57)Cai Y, et al. (2025) Sci Rep, 15: 9347.. Regional differences in breast cancer burden reflect disparities in health care systems and public health efforts. High-SDI regions have seen decreases in burden due to widespread screening, early detection, and advanced therapeutic interventions, whereas low-SDI regions have limited access to screening, diseases diagnosed at advanced stages, and limited, if any, access to advanced therapeutics.

Another emerging concern among public health experts is the rise in cancer diagnoses among adolescents and young adults (AYAs), defined as individuals ages 15 to 39 years. The global burden of AYA cancers is expected to increase by 12 percent from 2022 to 2050 (58)Hughes T, et al. (2024) Lancet Oncol, 25: 1614.. The most common cancers diagnosed in this population include cancers of the breast, thyroid, cervix, blood (leukemia), and colon and rectum, cumulatively accounting for more than 50 percent of all new cases.

As cancer rates rise globally, so does the economic burden of the disease. From 2020 to 2050, the cumulative global economic cost of cancer is projected to reach $25.2 trillion. The cancers contributing most to this burden include those of the trachea, bronchus, and lung; colon and rectum; breast; and liver; as well as leukemia, with the United States and China accounting for the largest share of these costs (61)Chen S, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 465..

To ensure equitable progress against cancer worldwide, global medical research communities must collaborate to share best practices and implement innovative strategies tailored to local needs. Aligning cancer research funding with the global distribution of cancer burden and treatment availability is essential. Public health experts emphasize priorities for low- and middle-income settings, including reducing advanced cancer cases; improving access, affordability, and treatment outcomes; adopting value-based care, for which providers are paid based on patient outcomes and not just volume of patients; advancing implementation research; building research capacity; and leveraging technology (62)Pramesh CS, et al. (2022) Nat Med, 28: 649.. Efforts must also focus on preventing and treating infection-related cancers, while increasing investment in cancer surgery and radiotherapy—critical components in the curative treatment of many solid tumors (63)McIntosh SA, et al. (2023) Lancet Oncol, 24: 636.(64)Al Sukhun SA, et al. (2024) JCO Glob Oncol, 10: e2400015..

Funding Cancer Research: A Vital Investment

The immense toll of cancer is felt both in the number of lives it affects each year and its economic impact. The direct medical costs of patient care are just one measure of the financial impact of cancer, and in the United States alone, these costs were estimated to be nearly $209 billion in 2020 (6)American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Accessed: June 13, 2025.. Unfortunately, these costs stand in stark contrast to the NCI budget of $6 billion for the same year. Notably, direct medical costs do not include the additional burden of lost productivity due to cancer-related morbidity and mortality (see Investing in Research to Achieve a Healthier Future, p. 209). For example, the lifetime productivity losses among US AYAs diagnosed with cancer in 2019 were estimated at $18 billion (65)Parsons SK, et al. (2023) J Clin Oncol, 41: 3260..

Patients with cancer shoulder a large amount of the economic burden associated with cancer care. In 2019, the national economic burden associated with cancer care on patients was estimated to be over $21 billion (66)Yabroff KR, et al. (2021) J Natl Cancer Inst, 113: 1670.. Of this amount, nearly $5 billion was attributed to time costs—the value of patients’ time spent traveling to, waiting for, and receiving care—while an estimated $16.2 billion was attributed to out-of-pocket costs for cancer-related medical expenses (66)Yabroff KR, et al. (2021) J Natl Cancer Inst, 113: 1670..

With the number of new cancer cases projected to increase in the coming decades, both direct and indirect costs of cancer care are expected to rise substantially. A recent analysis estimated that the economic burden of cancer in the United States will reach $5.3 trillion over the next three decades (61)Chen S, et al. (2023) JAMA Oncol, 9: 465.. This rising economic toll highlights the urgent need for continued investment in cancer research to accelerate the pace of progress and curb the increasing burden of cancer on patients, families, and the health care system.

As the world’s largest public funder of medical research, NIH has long received bipartisan support from US lawmakers. For most of the past decade, consecutive increases in the NIH budget have helped maintain the momentum of progress against cancer and other diseases (see Sidebar 5). However, in fiscal year (FY) 2024, NIH funding declined for the first time in nearly a decade, breaking a trend of steady growth. NIH funding remained stagnant in FY 2025, with appropriations held flat at FY 2024 levels, marking the second consecutive year without an increase in the agency’s budget (see Figure 25). Meanwhile, the cost of conducting medical research continues to rise, driven by inflation and the increasing complexity of scientific investigations and clinical trials, which often require advanced technologies and highly specialized personnel.

Challenges posed by two consecutive years of stagnant NIH funding were compounded in early 2025, when the administration implemented broad federal budget cuts, resulting in the termination of more than 2,200 research grants and the loss of nearly $3.8 billion in unexpended research funding (79)Association of American Medical Colleges. Impact of NIH Grant Terminations. Accessed: June 30, 2025.. Training and career development grants have been especially affected, with hundreds of canceled awards intended to support graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and early-career investigators. These abrupt losses have fueled growing uncertainty within the research community and prompted many US-based scientists to consider opportunities abroad in countries with more stable funding environments (see Investing in Research to Achieve a Healthier Future) (80)Witze A (2025) Nature, 640: 298..

Proposed appropriations for FY 2026 suggest continued threats to NIH’s capacity to conduct and fund medical research. These funding cuts come at a time when other nations are rapidly expanding their cancer research efforts and have now surpassed the United States in initiating oncology clinical trials (81)Plackett B (2025) Nature, 640: S58.. Without strong federal support for research, the United States risks losing its position as a global leader in scientific discovery, innovation, and the development of lifesaving cancer treatments (81)Plackett B (2025) Nature, 640: S58.(82)Baker S (2023) Nature.. Beyond institutional disruptions, the impact on public health could be profound. Researchers estimate that proposed NIH funding cuts could result in more than $8 trillion in economic losses over the next 25 years, driven by a decline in new therapies and reduced life expectancy (83)Cutler DM, et al. (2025) JAMA Health Forum, 6: e252791..

Discoveries fueled by NIH funding have transformed cancer prevention, detection, and treatment, turning once-fatal diagnoses into manageable conditions, saving millions of lives, and offering hope to millions more. Sustained and predictable federal funding is essential to preserve US leadership in biomedical research, safeguard progress against cancer, support the development of future cancer researchers, and ensure that future generations continue to benefit from scientific breakthroughs in the quest to end cancer (see AACR Call to Action).

Next Section: Understanding the Path to Cancer Development Previous Section: Snapshot of a Year in Progress