- Funding for Research and Programs That Address Disparities and Promote Health Equity

- Collaborative Resources to Advance Research for Health Equity

- Public Health Policies to Regulate and Reduce the Use of Tobacco Products

- Achieving the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in the U.S. by Addressing Disparities

- Policies to Address Obesity, Poor Diet, and Physical Inactivity

- Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Screening

- Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers in Trial Design

- Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers for Patients

- Improving Access to High Quality Clinical Care

- Coordination of Health Disparities Research and Programs within the Federal Government

Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities through Science-based Public Policy

In this section you will learn:

- Federal agencies including the NIH, NCI, CDC, and FDA play an important role in addressing cancer health disparities, and funding for research and programs at these agencies is vital for making progress.

- Strong public health policies can help reduce cancer health disparities by improving prevention and early detection of many cancers.

- Recommendations exist for improving diversity in clinical trial enrollment, but action is needed to make sure these recommendations are put into practice.

- Policies that improve access to high quality clinical care are critical for ensuring that advances across the cancer care continuum benefit all and reduce disparities.

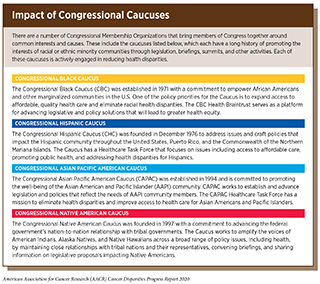

Meaningfully reducing cancer health disparities will require a multipronged approach that supports individuals, communities, health centers, and local, state, and federal governments to resolve disparities in cancer prevention, screening, treatment, survivorship, and precision medicine (see sidebar on Impact of Congressional Caucuses). In this chapter, policy-based solutions will be presented for Congress and federal departments and agencies, including the HHS and its relevant operating units, the NCI, the FDA, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), among others. Federal coordination, program management, research prioritization, and funding are policy levers that can accelerate the reduction of health disparities across the cancer care continuum.

Funding for Research and Programs That Address Disparities and Promote Health Equity

Federal funding through agencies including the NIH, NCI, and CDC plays a vital role in our efforts to understand and address cancer disparities. Research programs that incorporate a disparities focus can deepen our knowledge of factors that lead to poorer health outcomes in different populations. For example, the NIH’s All of Us program, funded by the 21st Century Cures Act, emphasizes inclusion of historically underrepresented populations to improve precision medicine research. The NIMHD is a global leader in supporting research on the many factors that lead to disparate health outcomes, including nonbiological variables such as socioeconomics, politics, discrimination, culture, and environment.

The NCI has many programs that aim to reduce cancer disparities (see sidebar on NCI Programs That Address Disparities in Cancer Prevention and Care. Continued, robust funding for these programs is essential for reaching patients who may often be underrepresented in cancer research and to build the capacity of researchers working to reduce cancer disparities. For example, the NCORP brings clinical research studies directly to individuals in communities across the country and actively seeks to include minority and underserved individuals in its programs. The NCI CRCHD plays an important role in supporting research on cancer disparities as well as training for a diverse cancer research workforce.

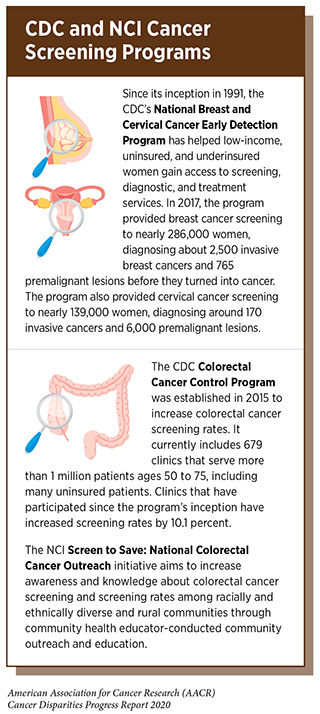

The CDC also leads many programs that are critical to addressing cancer disparities, including the National Program of Cancer Registries (NBCR), the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH), and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program. Federal funding for these programs allows the CDC and its local partners to collect data and reach individuals in diverse communities with key services and information.

Collaborative Resources to Advance Research for Health Equity

As discussed earlier in the report (see Why Do Cancer Health Disparities Exist?), disparities in cancer health outcomes are due to a mix of social, clinical, biological, and environmental factors, and there is ongoing research to investigate the complex interplay among these factors. Government agencies, private funders, and the research community have been collaborating on efforts to identify, prioritize, and generate resources that can support and advance such research.

Social determinants of health, including racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors, impact cancer care and outcomes. The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. In the U.S., there is increasing recognition of the importance of documenting, analyzing, and improving the way social determinants of health impact individuals’ health, as reflected in the HHS domestic health strategy document, Healthy People 2020. However, there are not yet consistent methods for defining and collecting data on social determinants of health. For example, most health researchers include demographic characteristics such as area of residence, education level, geographic origin, and genetic ancestry, while some researchers also include characteristics such as language fluency, health literacy, housing, and food security. At a recent workshop of the National Cancer Policy Forum of the National Academies, participants agreed that the most useful immediate action would be for the federal government to convene stakeholders to develop a consensus on standard language and definitions for social determinants of health, as well as to create an efficient process to elicit and document these characteristics during patient care and in research studies. As methods are developed to collect this information from patients, for example through the electronic medical record, it will be important to address patient privacy concerns through appropriate safeguards.

Precision medicine promises to transform medical care by creating tailored treatments for individual patients depending on their specific genetic background (see Imprecision of Precision Medicine). To ensure that these new medical advances help to close the gap in cancer disparities, it is critical that sample and data repositories include representation from individuals of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, patients from these groups should be provided appropriate genetic counseling in order to understand and make informed choices about their care based on their genetic information.

While TCGA and similar projects focus on genetic information from individuals with cancer, the NIH All of Us Research Program is gathering information from the genomes of one million healthy individuals. The program was designed to recruit from groups historically underrepresented in biomedical research, and 80 percent of the initial cohort of 230,000 individuals come from such groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, rural residents, and sexual and gender minorities (349) Special Report: The “All of Us” Research Program. 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 15].. The All of Us program will also provide genetic counseling to all of its participants, ensuring that it is a valuable resource for studying and narrowing health disparities.

Public Health Policies to Regulate and Reduce the Use of Tobacco Products

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of cancer and cancer-related deaths and has been linked to 18 different cancers (see Disparities in the Burden of Preventable Risk Factors). Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. and a disproportionate number of racial and ethnic minorities die of this disease. Policy interventions such as smoke-free laws, added taxes on tobacco products, limitations on advertising for tobacco products, smoking cessation programs, and public health campaigns have succeeded in lowering the national smoking rate over the past 50 years. However, these policies have had limited benefits for racial and ethnic minority groups.

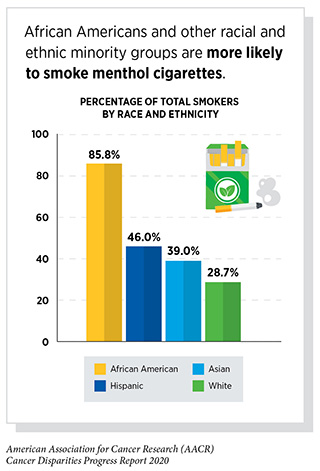

Differential tobacco product use by racial and ethnic minority groups is linked to differences in marketing and regulation of tobacco products used by minority groups. The prime example of this is the continued availability of menthol cigarettes—a tobacco product favored by African American smokers—following a federal ban on other flavored cigarettes. Menthol cigarettes constitute about one-third of the total cigarette market, and are preferred by African Americans, young people, women, Hispanics, and those with lower socioeconomic status. Insider documents from tobacco companies revealed that in order to maintain or increase market share for menthol cigarettes, African American and urban neighborhoods were specifically targeted with aggressive marketing and sales tactics (382)Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Cent Behav Stat Qual [Internet]. 2017;1–2889.[cited 2020 Jul 15].

Menthol cigarettes have been associated with numerous public health problems, including increased initiation of smoking and progression to habitual smoking particularly for young people, increased craving of and dependence on cigarettes, and reduced success in smoking cessation particularly for African American smokers (144)Villanti AC, Collins LK, Niaura RS, Gagosian SY, Abrams DB. Menthol cigarettes and the public health standard: a systematic review. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 23];17:983.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Menthol’s cooling and anesthetic properties mask the harsh taste of tobacco and feel of cigarette smoke. Yet when Congress banned flavored cigarettes through the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act), lawmakers allowed the popular menthol cigarettes to remain on the market and asked the FDA to determine the impact of menthol cigarettes on public health.

In 2011, the FDA Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) delivered its mandated report recommending that “removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit public health in the United States” (383)U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary scientific evaluation of the possible public health effects of menthol versus nonmenthol cigarettes. US Dep Heal Hum Serv [Internet]. 2013;[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Subsequently, the FDA was sued by tobacco companies and a judge ruled that the agency could not act on the advice of the TPSAC. The FDA appealed and the ruling was overturned in January 2016, allowing the agency to use the TPSAC report to inform rulemaking. The FDA also conducted its own independent evaluation of the public health effects of menthol cigarettes and similarly concluded that it was “likely that menthol cigarettes pose a public health risk above that seen with nonmenthol cigarettes (383)U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary scientific evaluation of the possible public health effects of menthol versus nonmenthol cigarettes. US Dep Heal Hum Serv [Internet]. 2013;[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Despite the 2016 court ruling and the consensus of internal and external experts on the negative public health impact of menthol cigarettes, the FDA has not issued any final regulations banning menthol cigarettes. The agency has issued several advanced notices of proposed rulemaking and made announcements that it intends to remove menthol cigarettes, but to date has not followed through on its intentions. The AACR and public health groups have repeatedly called on FDA to remove menthol cigarettes from the marketplace, including through a formal Citizen Petition in 2013 (384)Citizen Petition Asking the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to Prohibit Menthol as a Characterizing Flavor in Cigarettes. 2013;[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

The continued availability of menthol cigarettes in the marketplace contributes markedly to the national smoking rate and to disparities in tobacco use and subsequent disease. There are several policy mechanisms to address these disparities, including FDA regulatory action and legislation directing FDA to exercise its regulatory authority. Local governments have begun to consider banning menthol cigarettes within their localities, beginning with San Francisco in 2018. The debate over flavors in tobacco products heated up in 2019 in response to the epidemic rise in use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), which was sparked in part by flavored e-cigarettes. The federal government, states, and localities all have instituted or have considered instituting bans on flavored e-cigarettes. As public discourse, regulation, and legislation advance on flavored e-cigarettes, it is important to remember the role that menthol cigarettes continue to play in maintaining the national smoking rate.

Some opponents of a federal ban on menthol cigarettes fear that it would result in enforcement actions on consumers, who are primarily minorities. A federal ban implemented by the FDA would set limits on menthol product content for cigarette manufacturers. States and localities are instituting bans on the sale of menthol cigarettes. Federal, state, and local policy actions should make it clear that compliance is directed at manufacturers and retailers, not consumers. From a public health perspective, surveys show that almost half of menthol smokers would quit if menthol cigarettes were not available. Menthol cigarettes continue to be a growing share of the cigarette market, so removing menthol cigarettes would contribute to further lowering the smoking rate. Given the fact that menthol makes it harder to quit smoking, it will be important to couple a ban on menthol cigarettes with smoking cessation resources and programs to support minority smokers, including cessation medication and counseling support.

Achieving the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in the U.S. by Addressing Disparities

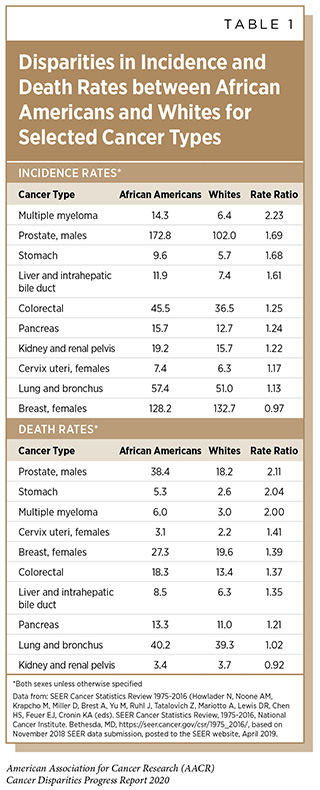

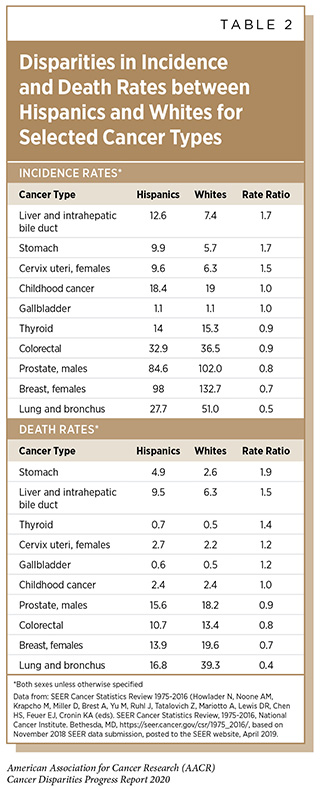

Cervical cancer is one of the most highly preventable cancers because of effective vaccines for the causative agent, HPV, as well as available screening and treatment methods for pre-cancerous cervical lesions. Because of these preventative measures as well as available treatment for invasive cervical cancer, the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health concern (defined by the World Health Organization as an incidence of 4 or fewer cases per 100,000 women) is now an ambitious but feasible goal by 2030 in the U.S. The public health strategy for cervical cancer elimination includes improved HPV vaccine coverage to 80 percent of eligible adolescents, increased screening and treatment of cervical precancer to 93 percent of eligible women, and prompt treatment of invasive cancers. But the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health concern cannot be achieved in the U.S. without addressing the current disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates. Although overall cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the U.S. has been decreasing, African American and Hispanic women still have higher rates of cervical cancer incidence and death than white women and non-Hispanic women, respectively (see Tables 1 and 2).

Recent HPV vaccination rates are nearing parity between racial and ethnic minority groups, but HPV vaccination rates for all groups are still below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80 percent of eligible adolescents. Long-standing racial and ethnic gaps in HPV vaccination have narrowed in recent years for young adolescents, in part due to insurance coverage through the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion. In 2018, African American, Hispanic American, Asian American, and multiracial American adolescents were all vaccinated at the same rate or significantly higher rates than white American adolescents (32)Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, et al. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 11];68:718–23.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Still, only 51.1 percent of adolescents ages 13 to 17 received the full course of HPV vaccination in 2018. Continued coverage of HPV vaccines by health insurance is important for patient access, and culturally sensitive and tailored communication between providers and parents or patients is critical to improving vaccination rates among minority groups.

There are ongoing disparities observed in cervical cancer screening and treatment. Lower cervical cancer screening rates are observed for Hispanic women, women who are less educated, and women living in poverty (see Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection). African American and Hispanic women are less likely than white women to receive the treatment that is recommended by clinical guidelines (385)Uppal S, Chapman C, Spencer RJ, Jolly S, Maturen K, Rauh-Hain JA, et al. Association of Hospital Volume With Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer Treatment. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 27];129:295–304.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

To close the gaps in cervical cancer screening and treatment, expanded funding and implementation are needed for programs such as the CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, which currently provides nearly 139,000 low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women annually with access to screening, diagnostic, and treatment services (see sidebar). As further discussed below, greater efforts are needed to provide underserved minority patients with access to better quality care, which in this case means guideline-recommended treatment for invasive cervical cancer.

Policies to Address Obesity, Poor Diet, and Physical Inactivity

Addressing cancer prevention disparities in obesity, nutrition, and physical activity will require research to better understand the social determinants of health that impact these disparities. For example, the HHS and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) publish the Dietary Guidelines for Americans every five years as a source for Americans on nutrition. However, the 2015 Guidelines Advisory Committee was not able to address disparities in nutrition because of a lack of literature in this area. Future efforts would be supported by more funding of research on disparities in nutrition.

Community programs such as those funded by the CDC Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health demonstrate how to encourage individual behaviors such as physical activity, nutrition, and obesity reduction. There also needs to be an evaluation of how to impact structural determinants of health that impact communities, e.g., factors such as food deserts, sidewalks and green space for activity, and noise and light exposure that disrupts sleep. This work will require input from and collaboration with sectors outside the health sector. To make real progress will require prioritization at an interagency level or through legislative directives from Congress.

Policies to Address Disparities in Cancer Screening

Screening rates for several cancers are lower in racial and ethnic minority groups than in the general population (see Disparities in Cancer Screening for Early Detection. Mechanisms to reduce screening disparities include funding research studies to define the biological and environmental differences in disease etiology between populations, improving tests and updating screening criteria for high-risk minority groups, and supporting patient access to and utilization of screening tests.

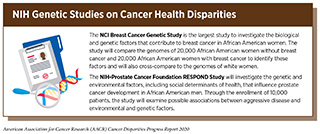

There are gaps in current knowledge about how biological and environmental differences between groups contribute to the development and progression of specific cancers. There is a significant need for funding and infrastructure to investigate and identify the underlying genetics, biomarkers, and other factors that indicate advanced disease progression. The NCI coordinates two such research studies to examine differences in cancer etiology—the NCI Breast Cancer Genetic Study in African American women and the NIH-Prostate Cancer Foundation RESPOND study (see sidebar on NIH Genetic Studies on Cancer Disparities). These two studies will provide valuable data that can be used to inform breast cancer and prostate cancer screening protocols for high-risk African Americans. It will be important to ensure that the results from these two studies are translated into guidelines and programs such as genetic testing and counseling. Increased funding and infrastructure are critical to support additional research studies in other cancers, as well as program implementation.

The USPSTF is responsible for reviewing evidence for clinical preventive services, reporting research gaps to Congress and the health community, and providing recommendations for screening and other preventive services. In its 2018 report, the USPSTF noted important research gaps in screening for cervical cancer among diverse populations, including studies to identify and evaluate effective strategies to reach unscreened and inadequately screened women (388)Eighth Annual Report to Congress on High-Priority Evidence Gaps for Clinical Preventive Services – US Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 27].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The USPSTF also identified research gaps in screening for prostate cancer among African American men and men with a family history, including studies to develop and validate tools and tests to distinguish between slow-growing and aggressive prostate cancer. It is the responsibility of research agencies such as NCI to prioritize and fund research to fill the gaps.

The research evidence base must be promptly translated into customized screening guidance for at-risk groups. A recent study found that the current USPSTF screening guidelines for lung cancer identified only 32 percent of African Americans with lung cancer in the study population, compared to 56 percent of white Americans (389)Aldrich MC, Mercaldo SF, Sandler KL, Blot WJ, Grogan EL, Blume JD. Evaluation of USPSTF Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines Among African American Adult Smokers. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 27];5:1318.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. African Americans in the cohort study tended to develop lung cancer at earlier ages and after fewer pack-years of smoking. Researchers recommended that the USPSTF screening guidance account for race-related differences in risk and lower the age and smoking history criteria required to deem African American smokers eligible for lung cancer screening. It is also important to note that African Americans were underrepresented (4 percent) in the initial study population used for the development of the USPSTF lung cancer screening guidance (389)Aldrich MC, Mercaldo SF, Sandler KL, Blot WJ, Grogan EL, Blume JD. Evaluation of USPSTF Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines Among African American Adult Smokers. JAMA Oncol [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 27];5:1318.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Studies such as this highlight the importance of prioritizing research on disease etiology in minority populations and translating the resulting evidence into customized screening criteria for populations with different levels of risk. The Congressional Tri-Caucus has recognized this as an important issue, putting forth a legislative proposal in the Health Equity and Accountability Act of 2018 to direct the Secretary of HHS to convene experts to develop guidelines for disease screening in minority populations that have higher than average risk for chronic diseases including cancer.

Another mechanism for closing screening gaps is requiring public and private insurance to cover cancer screenings as essential health benefits for patients. For example, the Affordable Care Act requires Marketplace plans to provide without cost-sharing colorectal cancer screening for adults ages 50 to 75, tobacco use screening, and lung cancer screening for adults ages 55 to 80 who are at high risk for lung cancer (390)Preventive care benefits for adults | HealthCare.gov [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 27].[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Research examining the effects of the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion shows mixed impact on the utilization of cancer screening services in minority populations. The evidence suggests that insurance coverage may be necessary to provide access to these services, but other approaches are needed to promote utilization of screening tests.

Beyond providing minority populations with greater access to evidence-based screening tests, additional efforts including patient engagement, education, and local community outreach services are important to increase cancer screening rates. The NCI National Outreach Network and Screen to Save: National Colorectal Cancer Outreach and Screening Initiative (see sidebar on CDC and NCI Cancer Screening Programs) help provide resources, materials, and infrastructure for outreach and education. The CDC works extensively to increase access and utilization of cancer screening services through local and community programs funded by the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP). The CRCCP currently funds clinics and health systems through 23 states, six academic centers, and one tribal grantee, and clinics that have been enrolled for the two years of the program have increased screening rates by 8.3 percent. Increased funding would enable the program to expand to other states, where there is an ongoing need to address disparities in colorectal cancer screening. Continued funding support for these programs is critical, and similar programs for other cancers such as prostate and lung cancer should be considered.

Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers in Trial Design

Historically, clinical trial populations have been relatively homogeneous, leading to the approval of medical products that have not been adequately tested in a real-world, representative sample of the patients who will use them (see Disparities in Cancer Treatment. There are ongoing government and stakeholder initiatives to broaden clinical trial participation, but more must be done to prioritize these activities and consider how to incentivize or require the participation of academic and industry decision makers.

Eligibility criteria for clinical trials represent patient characteristics that are used to include and exclude patients for clinical trial enrollment. These criteria are intended to protect patient safety by limiting adverse events during testing of new investigational agents, but often exclusion criteria are used by default due to historical precedent. In 2018, the NCI broadened its recommended eligibility criteria for NCI-sponsored clinical trials, building on a stakeholder initiative begun by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Friends of Cancer Research (287)Kim ES, Bruinooge SS, Roberts S, Ison G, Lin NU, Gore L, et al. Broadening Eligibility Criteria to Make Clinical Trials More Representative: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Friends of Cancer Research Joint Research Statement. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 27];35:3737–44.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The NCI guidelines support greater inclusion of patients who were previously excluded due to brain metastases, HIV/AIDS status, organ dysfunction (i.e., liver, kidney, and heart), prior and current malignancies, history of hepatitis B or C, and pediatric status (391)NCI. NCI Recommended Protocol Text and Guidance based on Joint Recommendations of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Friends of Cancer Research (Friends). 2018;1–9.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. While the NCI guidelines are a welcome first step, they do not address the exclusion of patients with common chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, which leads to the exclusion of many underrepresented minority patients.

In 2019, the FDA issued a draft guidance for industry with its recommendations to enhance the diversity of clinical trial populations, developed following a public stakeholder workshop (see sidebar on FDA Recommendations for Broadening Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Design) (392)U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration Food and Drug. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations — Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Draft Guidance for Industry. 2019;June 2019:1–18.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. In addition to covering the issues raised in the NCI guidelines, the FDA guidance also addresses two primary reasons for the exclusion of patients with common chronic conditions: 1) concerns that patients may experience more adverse effects because the drug interacts with other medications the patient takes, and 2) concerns that these patients may add noise to the data, making it more difficult to determine the investigational drug’s safety or effectiveness. Through the use of adaptive trial design, earlier or additional analysis of patients with comorbidities, and progressive relaxation of exclusion criteria, drug developers can broaden their clinical trial populations without reducing the chances of successfully measuring efficacy and safety. The guidance, while not legally enforceable, reflects the FDA’s current thinking and presents recommendations for companies to consider during drug development.

Improving the workforce diversity of those who are designing clinical trials will provide an opportunity to bring in new ideas that could revolutionize the conduct and representation of clinical trials (see Overcoming Cancer Health Disparities through Diversity in Cancer Training and Workforce. It will be important to include and appreciate the insight from clinicians who are caring for patients with comorbidities and others who are routinely excluded from eligibility. The workforce diversity could come from recruiting investigators from minority-serving institutions, and historically black colleges and universities, and minority investigators at both cancer centers and institutions that are not currently doing clinical trials.

Guidance from the FDA, NCI, and other federal government agencies represents an important first step in changing eligibility criteria and clinical trial design, but recommendations may not have much impact without incentives or mechanisms of enforcement. As this is a priority issue that affects the development and availability of cancer therapeutics and continues to impact cancer health disparities, it is important for policy makers to engage with stakeholders to identify mechanisms that will change long-standing industry and academic patterns and make clinical trials more accessible to all patients. Government agencies could begin by requiring the reporting of criteria that lead to the exclusion of minority patients, which would help identify key criteria to be examined and expanded. NCI funds cancer centers through competitive cancer center support grants. As part of the grant renewal process, cancer centers could be held accountable for the diversity metrics of trials in their centers. Cancer centers should strive for meaningful inclusion of minority populations in their center trials based on both the disease burden and diversity of the center’s catchment area. Legislators could consider mechanisms that provide companies with FDA priority review or other incentives for meeting specified inclusion benchmarks in trials conducted in the United States.

Diversifying Representation in Clinical Trials by Addressing Barriers for Patients

Surveys demonstrate that while minority patients show a high willingness to participate in clinical trials, there are many barriers that prevent them from participating including geographic, financial, and other environmental/social/cultural factors (393)Barriers to Patient Enrollment in Therapeutic Clinical Trials for Cancer | American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 27].[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

Many underrepresented minority patients do not even consider enrolling in a clinical trial because they do not live close to a trial site or are not provided information by their health care provider. In its draft guidance, FDA recommends that companies ensure clinical trial sites are in areas with high concentration of racial and ethnic minority patients. Research networks such as NCORP aim to expand access to clinical trials through community sites that are outside of large research centers. Patient navigators, community health workers, and patient advocates who have built trust within communities have been shown to be critical in improving the enrollment and retention of minority patients. These staff also help ensure that patients are adequately educated and informed about available trials. Congress should consider providing increased funding and support for patient navigation services at federally funded trial sites.

Patients experience financial barriers to participating in clinical trials that include related medical costs, out-of-pocket costs, transportation costs, and other incidental costs. Time off from work with loss of pay is an added barrier for those in the workforce. The Affordable Care Act required private insurance companies to cover routine medical costs of participating in clinical trials, but more comprehensive support is critical for patients. Medicare also covers routine costs for clinical trials, but not all state Medicaid programs do. The Clinical Treatment Act would require Medicaid programs to provide that coverage. Other legislative proposals would require insurers to cover routine care costs at in-network rates, regardless of the provider’s affiliation. Proposals such as these would help patients who may be enrolling in a clinical trial outside their standard provider network. In its draft guidance, the FDA also recommended a number of considerations to address financial barriers including reducing the frequency of study visits and making patients aware of financial reimbursements during the recruitment process.

Improving Access to High Quality Clinical Care

A lack of access to quality clinical care is a critical element that contributes to cancer health disparities. insurance coverage is an important factor that increases patient access to health care services across the cancer care continuum, including prevention, screening, treatment, precision medicine, and survivorship resources. With the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), approximately 20 million people gained health insurance coverage through government exchanges or Medicaid expansion (394)The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Key Facts about the Uninsured Population. Henry J Kaiser Fam Found [Internet]. 2016;1–14.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. The ACA expanded Medicaid coverage to all individuals making less than 138 percent of the federal poverty line but some states refused federal funding for the expansion. In addition to expanding Medicaid, other changes that have been implemented as a result of the ACA are also helping to address the issue of access to health care, these changes include ensuring that the recommended cancer screening and prevention interventions are now more widely available and affordable to a greater number of people than ever before.

Overall, the ACA has increased an individual’s ability to access diagnostic and treatment options for cancer (395)Graves JA, Swartz K. Effects of Affordable Care Act Marketplaces and Medicaid Eligibility Expansion on Access to Cancer Care. Cancer J [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 27];23:168–74.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. While it is still too early to examine long-term impacts, some research suggests that Medicaid expansion has had a positive effect on increasing access to cancer care for groups of lower socioeconomic status, including lower income individuals from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds (396)Choi SK, Adams SA, Eberth JM, Brandt HM, Friedman DB, Tucker-Seeley RD, et al. Medicaid Coverage Expansion and Implications for Cancer Disparities. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Jan 27];105:S706–12.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Some studies have shown that the ACA and Medicaid expansion increased the rates of cancer diagnosis and has led to enhanced access to cancer care surgery (397)Eguia E, Cobb AN, Kothari AN, Molefe A, Afshar M, Aranha G V, et al. Impact of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid Expansion on Cancer Admissions and Surgeries. Ann Surg [Internet]. NIH Public Access; 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 27];268:584–90.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Another study demonstrated that cancer survivors in Medicaid expansion states had better access to care than survivors in nonexpansion states (398)Tarazi WW, Bradley CJ, Harless DW, Bear HD, Sabik LM. Medicaid expansion and access to care among cancer survivors: a baseline overview. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 27];10:583–92.[cited 2020 Jul 15].. Additionally, a recent study also showed that previous racial disparities in timely cancer treatment between African American and white patients practically disappeared in states where Medicaid access was expanded under the ACA (398)Tarazi WW, Bradley CJ, Harless DW, Bear HD, Sabik LM. Medicaid expansion and access to care among cancer survivors: a baseline overview. J Cancer Surviv [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2020 Jan 27];10:583–92.[cited 2020 Jul 15]..

However, having insurance coverage is only the first step in ensuring access to high quality clinical care. While more patients now have insurance coverage, patients with lower-tier insurance coverage may still not be able to get care at a given hospital because the hospital does not accept that insurance. Patients who are eligible for health care programs that serve the uninsured or underinsured may not be getting the minimum standard of quality care, which continues to exacerbate disparities. For example, many underserved minorities are receiving care from community cancer centers, community health centers, safety net centers, and Federally Qualified Health Centers. Other factors also impact access to quality care, including an individual’s geographical residence, bias in the health care system, and similar factors. New policies are needed to ensure that patients are receiving access to a minimum standard quality of cancer care.

Coordination of Health Disparities Research and Programs within the Federal Government

As described throughout this chapter, there are several initiatives in different government agencies aimed at addressing cancer disparities. Efforts to increase coordination across these programs would help maximize impact and raise the visibility and awareness of these initiatives. The NCI CRCHD manages and coordinates a number of disparities-related research and training programs. There is further opportunity to break down silos that exist between NCI’s clinical trial programs, including the broad NCI National Clinical Trials Network Program, the community-based NCORP, and the capacity-building Partnerships to Advance Cancer Health Equity and Geographic Management of Cancer Health Disparities Program. By creating a shared strategic plan, research framework, online portal, and other shared resources, NCI would be able to better measure and leverage the programs’ impact on cancer disparities research.

There are other opportunities to advance disparities research and health equity by creating innovative partnerships across government agencies. NIH has already begun efforts to promote and support disparities research across institutes, including NCI and NIMHD. These efforts should continue to be prioritized. As NCI seeks to address the complex issues of bias and other challenges in the health care workforce, there may be opportunities to create partnerships with HRSA and HRSA-funded community medical entities. Finally, as noted above, meaningfully addressing the impact of social determinants of health will require collaboration of HHS with other relevant agencies, including the USDA, Department of Justice, Department of Transportation, and others.